Measuring Time with chain of blocks

| If you find WORDS helpful, Bitcoin donations are unnecessary but appreciated. Our goal is to spread and preserve Bitcoin writings for future generations. Read more. | Make a Donation |

Measuring Time with chain of blocks

By Tamas Blummer

Posted March 16, 2019

Recent re-discovery of Bitcoin’s pre-release code reveals that Satoshi called the chain of blocks a time chain. Let’s investigate the suitability of the chain of blocks to measure time.

Miners have to set timestamps of their blocks within some bounds around the recent block times and also the time observed by other network participants otherwise the block will be rejected. Therefore block timestamps loosely follow real time.

The question I investigate here is not the accuracy of block timestamps, but if the number of blocks observed is a suitable measure of time.

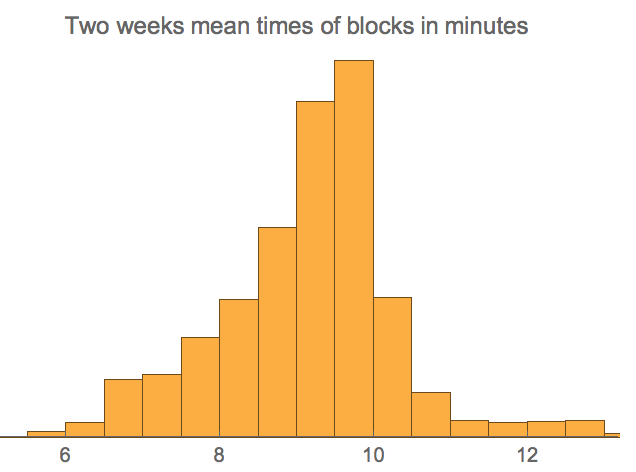

Bitcoin regularly re-calibrates difficulty at every 2016 blocks. The calibration target is that it should take two weeks (1209600 seconds) to produce 2016 blocks. There are several factors why this target will always be missed and a re-calibration of difficulty triggered:

- The difficulty controls the expected time to next block. The actual time is a stochastic process with known significant variance.

- The re-calibration uses block timestamps that miners are free to chose within some bounds.

- The computing capacity of miners keeps changing. This has the most significant influence that difficulty re-calibration is designed to deal with.

The variance of the stochastic mining process gives us a bound of precision we can expect, the other two will make matters even worse.

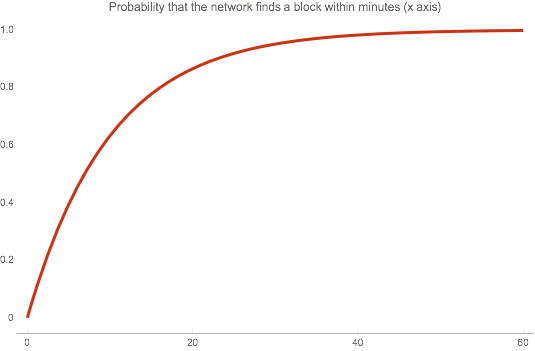

Since mining is a progress free guesswork its time to success is exponentially distributed with a mean of 10 minutes. Below an illustration of the probability that the network finds a block within some time span:

Fun fact: The probability to find a block within 10 minutes is not 0.5, but much more: 0.63. The mean time to success is 10 minutes, but its probability distribution is not “symmetrical” around that, since it assigns non-zero probability any long wait time.

The standard deviation of the success distribution is also 10 minutes therefore we should not expect the time measurement to be more precise than that. Reality is likely worse. Let’s see how bad.

Absolute time

Let us take Bitcoin’s first 556875 blocks that were produced (according to miner set timestamps) between 2009–01–03 18:15:05 and 2019–01–03 18:19:56. that is roughly 10 years or precisely 315533091 seconds.

The target time span for 556875 blocks is 556875/2016*1209600 =334125000 seconds, which means the Bitcoin clock was ticking significantly faster than target. We should have had that many blocks 215 days later.

This should not surprise us since Bitcoin’s mining difficulty was skyrocketing during its first 10 years, due to ever increasing mining capacity and consequently faster than target block production.

Measuring time with computation

A block on the chain had to be created after its predecessor, since it had to include the previous hash into its computation. Therefore the work spent for a block was sequential to the work spent for the previous one. The progress of the chain of blocks is therefore result of sequential calculation even though the calculation for the individual block is highly parallelizable.

Producing n blocks requires computation that is expected to take n*10 minutes in total. The difficulty adjustments based on timestamps are only there to periodically adjust for measurement errors, the actual tool of time measurement is the computation itself.

If the hardware that executes the computation was known and constant then there would be no need for a difficulty adjustment.

Any inaccuracy of the bitcoin clock in excess of the variance implied by the stochastic nature of mining is attributable to fluctuation of the network’s computing capacity and inaccuracy of block timestamps.

It is impossible to quantify the inaccuracy introduced by incorrect block timestamps as no one has an objective record of the time points the blocks were really created. The inaccuracy is however limited through this source as Bitcoin nodes reject to append a block with a timestamp more than two hours ahead of their own system time.

Incorrect timestamps lead to incorrect estimation of network computation speed. There is potential but never observed and soon to be fixed “time warp attack” on Bitcoin that could multiply the effect of incorrect timestamps. This source of inaccuracy had negligible effect on difficulty adjustments in the past and will be even less significant in the future.

The network however regularly underestimated its own computing speed.

Number of blocks produced is a proxy for the time passed, but this clock is severely skewed on the long run and highly imprecise on the short term. It is really bad, but still the best unforgeable time measure we have.