Map of the Bitcoin Network

| If you find WORDS helpful, Bitcoin donations are unnecessary but appreciated. Our goal is to spread and preserve Bitcoin writings for future generations. Read more. | Make a Donation |

Map of the Bitcoin Network

By Gloria Zhao

Posted July 22, 2020

A beginner-friendly “map” to help you navigate through the wide variety of nodes, software, and participants in the Bitcoin Network.

The Bitcoin network is often described as peer-to-peer (P2P), distributed, or decentralized. It’s often drawn as a homogeneous graph:

Or something similarly structured that suggests variation in the types of vertices and edges:

But what is a node, and what does it do? Is it a server or can it be a client… or both? Given the myriad of Bitcoin software, what “counts” as a node? How do all the participants in Bitcoin — users, miners, nodes, wallets — interact with one another?

This article draws a map of the Bitcoin network that clarifies these definitions and encapsulates some of the complexity. We’ll start by classifying the different types of nodes based on their server/client functionality and describing the P2P connections formed between them. Instead of providing statistics on the entire network, this article is primarily interested in enumerating the diverse set of possibilities in the network.

The Short Answer

Primarily, the vertices are nodes in the P2P network and the edges are their P2P connections. There are many different types of nodes that can be categorized based on their ability to serve other peers and clients; nodes can act as a server, client, or both at any given point in time.

Node = a participant on the P2P Network that implements the Bitcoin P2P protocol. A node isn’t required to run any specific software as long as it follows this protocol.

P2P Connection = a network connection directly established between two nodes communicating using the Bitcoin P2P protocol. We often use “peer” to refer to other nodes with which a node has a P2P connection.

Types of Nodes:

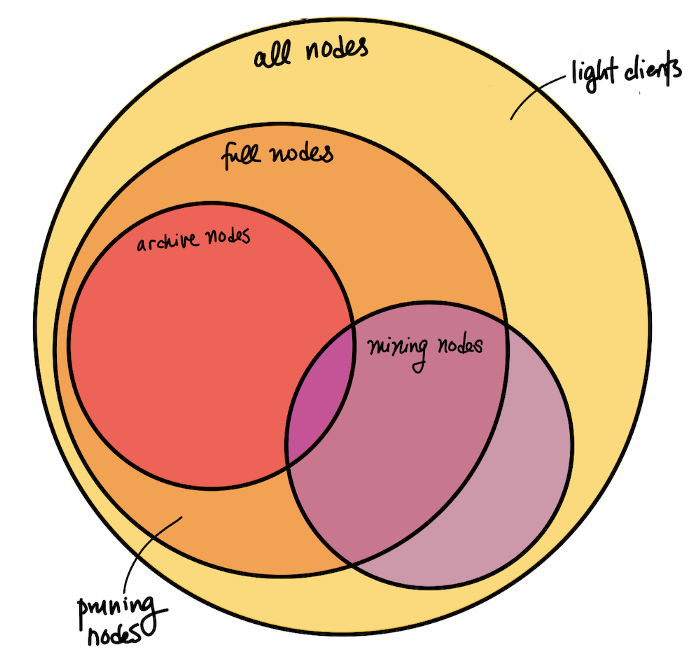

In the broadest sense, nodes fall into one of four categories based on how much state they maintain and what services they can provide.

Full Node (Fully Validating Node) = a node that is capable of validating transactions and blocks. Instead of searching through the blocks database every time, full nodes keep some state, i.e. a UTXO (unspent transaction output or “coins”) set.

Thus, Bitcoin nodes don’t necessarily need a complete copy of the blockchain in order to validate, as long as they maintain some block metadata and an up-to-date UTXO set. Pruning Nodes implement this exact behavior: they download and process blocks to build the necessary databases for validation, then discard the old blocks to save disk space. Since they have all of the information and can validate all new blocks and transactions, they are full nodes.

Archive Node = a node that has a copy of the entire history of the blockchain. These nodes are capable of validating incoming transactions and blocks, as well as querying block and transaction data from any point in history, including those that are no longer relevant to validation (hence the naming “archive”). It’s crucial that archive nodes exist, as new nodes need to catch up on the entire history in order to become full nodes. They can only do so by downloading the history, one block at a time, from archive nodes.

Mining Node = a node that produces new blocks. This involves keeping a mempool of unconfirmed transactions, validating new transactions, and solving the Proof-of-Work hash puzzle (i.e. finding the nonce) to construct a block. Mining nodes often use extra hardware to assist them in solving the hash puzzle (e.g. ASICs) or participate in mining pools. Technically, there are also non-full nodes that join a mining pool, connect to a full node that manages the pool, and help solve PoW on a block without doing any validation (so there are mining but non-full nodes).

Light Clients = generic term for a node that doesn’t keep the full state necessary for full validation and instead trusts other full nodes to do so. A light client may keep a limited amount of data in order to verify its own transactions, but not fully validate all blocks. Within Bitcoin Core, “light client” is often used synonymously with Simplified Payment Verification (SPV) Nodes, and not to be confused with Pruning Nodes. In some contexts, these aren’t called “nodes” because they don’t do most of the things [full] nodes usually do.

Here is an illustration of how these categories overlap:

Other Concepts for Nodes:

Nodes may also have additional characteristics that impact their participation on the network, but are not mutually exclusive with each other or any of the above four categories. Due to the decentralized nature and focus on accessibility in the Bitcoin ecosystem, as long as a node implements the P2P protocol and obeys consensus rules, implementation details and the decision to adopt features are within the node operator’s discretion.

Initial Block Download (IBD): a temporary state in which the node is not yet caught up to the current block height and is in the process of downloading the blockchain. A full node signaling that it keeps a full copy of the blockchain history may still be in IBD and thus be limited in the services it can provide (i.e. won’t be able to tell you about transactions that they haven’t seen yet). The getblockchaininfo RPC returns whether a node is in IBD.

Blocks Only Mode: a non-temporary mode in which the full node only validates blocks and the transactions in them. It does not validate any unconfirmed transactions (apart from its own), doesn’t keep a mempool, and asks its peers not to relay transactions to it.

Bitcoin Core: running the open-source software originally authored by Satoshi Nakamoto and currently maintained by various contributors, found at bitcoincore.org or from source. We know that Bitcoin Core isn’t the only software that exists in the Bitcoin P2P Network; some nodes run custom patches that implement specific behaviors, and some might use older versions of Bitcoin Core that don’t understand newly introduced protocol messages. It’s important to be cognizant of what new features require full network cooperation, not expect nodes to behave correctly or honestly, and account for node operators being hesitant or slow to upgrade their software.

Malicious: any type of behavior that intentionally harms the network (not including bugs, networking complications or other unintentional behavior). Bitcoin assumes a highly adversarial environment including the possibility of Denial of Service attacks, sybil/eclipse-attacks intended to double-spend, spy nodes trying to deanonymize addresses, etc.

Node as a Server

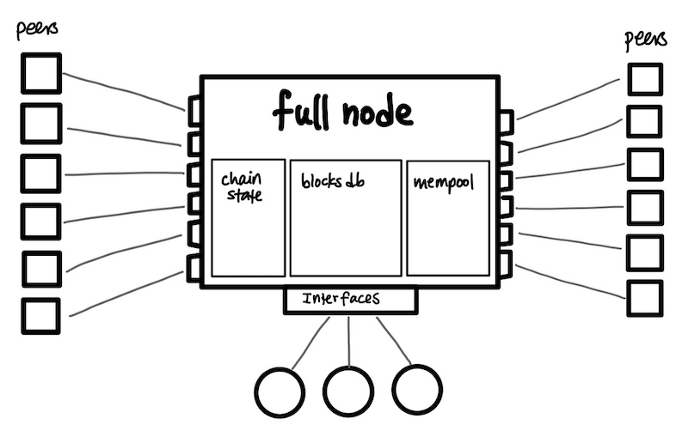

We’ve seen that each singular node is dependent on its peers to send the information it needs. Also, nodes typically serve a number of users and client software through non-P2P interfaces such as RPC, HTTP/REST, and a GUI.

Some examples of non-node clients that may use a node as a server:

- Users running a node to send and receive bitcoins.

- Wallets which manage keys, create transactions, and maybe keep some UTXO state associated with those keys but don’t have a copy of the blockchain and instead rely on a node to get up-to-date information.

- User-Facing Software Services and Applications such as block explorers, exchanges, and merchants that query full nodes for information and display them on a webpage or application.

- Developers creating nodes in regtest mode to test functionality or the interfaces themselves.

- Developer-Facing Software such as SDKs, APIs, and other interfaces. For example, the Bitcoin Core CLI (bitcoin-cli) uses the RPC interface to implement a command-line interface.

While these connections are not seen by a node’s peers on the P2P Network, they make up a significant portion of Bitcoin functionality. Bitcoin Core developers heavily consider these participants when developing new features or deciding what features to support.

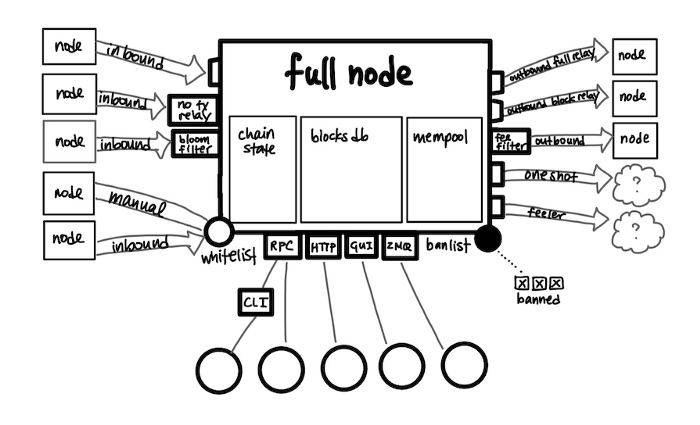

Now that we understand the node as both a server and a client, here’s what an individual node looks like at a high level:

Simplified view of a node

Simplified view of a node

Types of P2P connections:

P2P connections in Bitcoin all “speak the same language” in that they all use the P2P protocol to communicate, but are diverse in their conversation contents. The Bitcoin Core implementation attempts to balance stability (which prefers static connections) and accessibility (which encourages accepting connections from new nodes) through facilitating peer discovery and managing connections carefully. Bitcoin Core distinguishes between three main types of connections based on how they are initiated, which often informs the nature of the peer-to-peer relationship.

Outbound = automatic connection that your node initiated through peer discovery. Node discovery involves getting a list of IP addresses of established nodes to start out with, then a continuous and dynamic process of advertising your own address and attempting to connect to addresses you hear about. Depending on what your node needs (e.g. in IBD), it may prioritize connections that are able to provide specific services (e.g. serving past blocks and transactions).

Inbound = automatic connection that your peer initiated (to your peer, this connection is outbound). For security, inbound traffic is disabled by default and you need to configure some network and firewall settings to enable it.

Manual = connection that was made manually (e.g. through CLI or RPC) instead of automatically. You might create a manual connection because there’s a particular node operated by someone you trust or you’re testing the software and need to have control over the connections.

Other Concepts for P2P Connections:

Diversity in Outbound Connections

Outbound connections can be broken down into further categories based on the information received and duration of the connection.

Full-Relay outbound connections expect to communicate everything, including blocks, transactions, and addrs (used to find peers, similar to IP addresses, and not to be confused with wallet addresses used in transactions). Block-Only-Relay outbound connections only expect to receive blocks. Not to be confused with blocks-only mode; it is entirely normal for full nodes to establish Block-Only-Relay connections to 1–2 peers and Full-Relay connections to everyone else.

One-Shot and Feelers are temporary outbound connections used in node discovery. One-Shot connections are used to solicit a list of addrs that can be used to find new peers. Feelers are used to verify whether an addr corresponds to a real node.

Individual Differences

As we have seen, each node may provide different services and be looking for specific information from its peers. Every connection starts with a version handshake in which the nodes send information about themselves (e.g. best block height) and negotiate what to talk about (e.g. only interested in blocks). Connections may also change through subsequent messages, such as a fee filter message to communicate that they’re only interested in being relayed transactions with a minimum fee rate.

Discouragement, Disconnection, and Banning

Bitcoin Core nodes keep track of which peers behave in a way that indicates they may be malicious or running malfunctioning software. In response to such behavior, a node might choose to discourage (mark its misbehavior and perhaps disconnect in favor of new peers), disconnect, or ban the peer.

Permissions and Whitelist

Nodes also keep a list of permissions that each peer has, such as particular services it’s allowed to request or tolerance for misbehavior that would normally be penalized. Services are negotiated for every connection during the version handshake. Allowing misbehavior is often manually added for custom, personal light clients and nodes operated by people that trust each other. Related, nodes can also whitelist particular IP addresses.

Importance of Asymmetry

Note that each individual connection is bidirectional but asymmetric: the initiating peer may understand the connection to be a [full-relay] outbound, block-only-relay, feeler, or one-shot, but the receiving peer just sees an inbound connection with some established rules. This hides information through ambiguity about whether a node’s behavior reveals its internal mechanics or merely reflects the nature of the connection.

For example, if a node knows that its peer is in blocksonly mode (i.e. rejects all incoming transaction messages), it is obvious that all transactions sent from that peer correspond to its own wallet addresses. Instead, the receiving node just sees an inbound connection with transaction relay turned off. This could mean blocksonly mode, block-relay-only connection, or an idiosyncrasy of the connection.

A more detailed view of an individual node could look like this (note that the arrows’ directions just indicate which node initiates, not that the communication isn’t bidirectional):

Slightly less simplified view of a node

Slightly less simplified view of a node

“Full” Map

Each node has limited information about the network as a whole. Nodes really only see their own peers, and peers could be lying about what type of node they are. All peers could even be the same person in the event of an eclipse attack. This is an advantage for privacy and security because it applies to adversaries as well; having limited information makes targeted attacks more difficult. It’s possible to gather approximate information about how many nodes are in the network by creating lots of temporary connections, but this information is far from comprehensive.

For example, whether or not a node participates in a mining pool isn’t immediately apparent on the network. With approximate knowledge about which nodes are part of mining pools and observing how many blocks they mine, some websites are able to generate analytics on computing power proportions. However, they can be misleading as it is entirely possible for groups of nodes or even multiple mining pools to be operated by one entity.

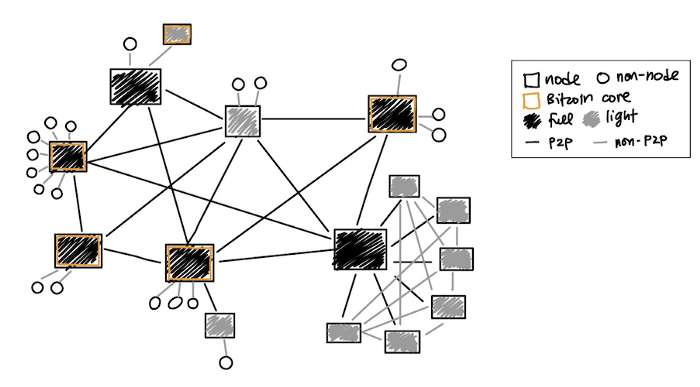

Putting it all together, we can imagine this simplified network map:

Simplified Network Map

Simplified Network Map

This map represents various possibilities instead of network size (which is very large) or topology (which is dynamic and unknown). Notice that the possibilities include:

- A Bitcoin Core full node with various clients connected via non-P2P interfaces, e.g. a user that downloaded the software from bitcoincore.org and is using the command-line or GUI to send and receive coins.

- Light clients that do their best to connect to a variety of full nodes in order to serve its own clients.

- A full node serving one or more light clients, perhaps an individual Bitcoin enthusiast who runs a full node using some cloud service provider and a more lightweight application on their personal device.

- A custom full node (e.g. a pool manager) connected to a group of custom light clients (e.g. individual pool participants) through both the P2P network and some private network.

Conclusion

Hopefully this post helped clarify what people mean when they say “node” and “P2P network,” and connect the dots on how all the participants in the network interact with one another. I hope it also provides some insight and “food for grep” on how Bitcoin Core implements peer-to-peer connections to protect privacy and enable new nodes to participate. Thanks for reading! :)

21 million thanks to John Newbery and Amiti Uttarwar for being very generous with their time helping me understand and document this information.