MPPs & Wumbo Channels - Optimizing Liquidity on the Lightning Network

| If you find WORDS helpful, Bitcoin donations are unnecessary but appreciated. Our goal is to spread and preserve Bitcoin writings for future generations. Read more. | Make a Donation |

MPPs & Wumbo Channels: Optimizing Liquidity on the Lightning Network

By Roy Sheinfeld

Posted September 14, 2020

Liquidity is all about flow. On the Lightning Network, bitcoin is the liquid, and the question is how much of it can move and at what speed. Payment channels are the network’s pipes, and until just recently, all pipes were fairly small, and a payment could only reside or flow through one pipe at a time. The liquidity was there, but it wasn’t flowing as well as it could have.

In the last few months, a couple of things have changed:

- Multi-Path Payments (MPPs) went live in May with LND 0.10, which splits payments into smaller parts and allows those parts to be and move in different places simultaneously.

- Wumbo channels went live in August with LND 0.11. They allow the nodes that share a payment channel to determine its capacity and to diverge from the old one-size-fits-all rule if they please.

We’ve talked about both MPPs and Wumbo channels before in the context of UX. Our thoughts back then were strictly focused on the user. But as we’ve been thinking more about the structural requirements of the network, including routing nodes, LSPs and the differences between users who mostly s(p)end and merchants who mostly receive, we realized that these two features have larger implications. MPPs and Wumbo channels have the potential to optimize liquidity throughout the network.

In this post, I’ll quickly recap what MPPs and Wumbo channels do, contrast them with standard payment channels, and explain how these two innovations change the face of Lightning.

Mario & Luigi would salivate at what Wumbo and MPPs can do. (Image: Phaidon.com)

Mario & Luigi would salivate at what Wumbo and MPPs can do. (Image: Phaidon.com)

Standard payment channels and their limitations

We’ve already covered standard payment channels in more depth here and here, so now I’ll just provide the need-to-know information:

- Two parties on Lightning can open a payment channel with an on-chain transaction.

- They can jointly commit a maximum of 0.1677 BTC to the channel, although they can reallocate that sum back and forth with off-chain transactions.

- Payments between two users without a direct connection are routed through intermediate nodes and channels until they reach their intended destination. 1 payment = 1 HTLC = 1 route.

- A channel stays open with the funds moving back and forth until it’s closed with an on-chain transaction by either party or by both together.

Standard channels limit users’ exposure to risk, but they fragment the network’s liquidity, which also restricts Lightning’s utility and convenience. Having access to only one limited local balance at a time and being able to route a transfer over a single route means that all users — but especially routing nodes — have to rebalance their channels often.

Like training wheels on a bike, standard channels were appropriate for a network that was just getting started, but at a certain point they started to impede our speed and progress. Standard channels were becoming an obstacle blocking the flow of liquidity over the network.

Wumbo channels

The limit on standard payment channels was designed to shield users from the risks associated with a new, growing network. The lnd software is still in beta, and nobody wanted incoming users to lose everything to unforeseen vulnerabilities.

After a few years of operation and tens of thousands of channels among thousands of nodes, Lightning has proven itself. So far, it’s turned out as safe and stable as we had all hoped. Wumbo channels are one of the rewards.

Wumbo channels are effectively standard payment channels without the limit (though there is discussion about implementing a new “soft” limit). They allow the users on either end to open a channel stocked with as much bitcoin as they like.

Wumbos as trunks

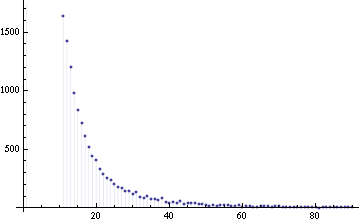

Just like the internet itself, Lightning is a network of networks. At the moment, only three nodes have more than 1000 public channels open, and as you scroll down the list of nodes, the number of nodes with a given number of channels increases as the number of channels decreases, more or less. The distribution roughly follows a power law. It looks kind of like this:

I’ve always thought that “Power Law” would make a great superhero name. (Image: Wikimedia)

I’ve always thought that “Power Law” would make a great superhero name. (Image: Wikimedia)

Few nodes have many open channels, and many nodes have few open channels. Most users are connected to a small subset of nodes — the routing nodes — that, in turn, have to maintain large amounts of liquidity on the channels among themselves to keep the funds flowing. (Yes, this is the issue of liquidity centrality. We’ve discussed it before here.)

Whereas most users wouldn’t notice a channel limit of 0.1667 BTC on most days, these routing nodes need trunk channels among themselves to handle much higher daily volumes. Wumbos allow a channel between two routing nodes to reflect the volume of transactions they handle. Routing nodes, including Breez, can now manage their liquidity over fewer channels and with fewer on-chain transactions. As Wumbos make operating nodes easier and cheaper, we’ll be able to spend even more time on innovating and improving the Breez client and Lightning as a whole.

Perhaps ironically, helping the network’s hubs also helps to decentralize it. Operating a high-capacity Lightning node isn’t trivial, and liquidity management is a big part of that challenging task. As it becomes easier to run a routing node, more people will opt to do so, which would help to decentralize the network. Alleviating headaches for existing Lightning operators simultaneously lowers the barriers to entry for incoming operators.

Wumbo hallelujah!

Multi-Path Payments (MPPs)

Even without limits, the maximum transfer size was — until recently — limited by a user’s balance on a given channel. Since each payment could only be contained in a single HTLC, and each HTLC could only handle a single route, the client would have to seek a single route with sufficient balances at each step. Forcing a payment along a single route meant that only a minuscule fraction of the network’s liquidity was available for a given transaction.

Standard channels and payments fragment the network’s liquidity into discrete, mutually inaccessible parts. While preserving ownership, MPPs pool that liquidity and put it at the network’s disposal.

How? MPPs teach LND to be patient. LND will first try to execute the payment as usual over a single channel/route. Should that attempt fail, because, say, the payment exceeds the fee limit or the relevant channel capacities, LND will try to send only half the amount. Once that half is en route, LND will search for a suitable path for the remaining half, splitting that half and repeating the process in case of failure. This process repeats until either the transfer succeeds (hooray!) or the minimum, indivisible transfer amount is reached.

And instead of expecting the entire sum to arrive at once, an HTLC sent via MPP tells the receiving node the total payment amount to expect. Thanks to a HODL invoice, the receiving node won’t settle the payment until the expected amount has arrived in full. Neither the sender nor the recipient need worry or care about how many parts made the journey over what routes.

Of course, Lightning never stands still. Even though MPPs only went live a few months ago, there are already plans to improve the algorithm. One interesting proposal is to split failed transfers by the Golden Ratio in order to approximate the Fibonacci sequence rather than simply halving them. The idea is to find the largest viable transfer size in fewer steps with less computation.

Another improvement being prepared by (ahem — Sorry. I need to clear my throat of false modesty.) our team is to first attempt the transfer with the user’s maximum local balance across all their channels rather than half the transfer amount. This would give users a better chance of being able to spend all their funds in a single payment, no matter how they are distributed across their channels.

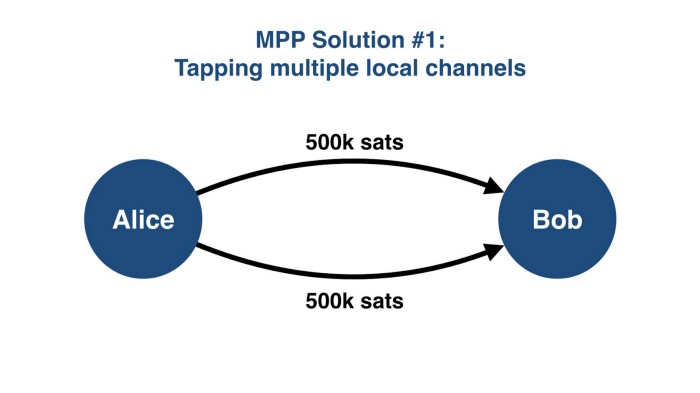

So let’s talk examples. Suppose Alice wants to send 1M sats to Bob. They share two channels, but Alice only has 500k sats in each. Without MPP, she can send him a maximum of 500k in a single payment. To send any more she would have to execute two separate payments.

And the same is true at Bob’s end. The rule of 1 payment = 1 HTLC = 1 route applies to the recipient too, so without MPP he can only receive 500k sats at a time from Alice.

MPP provides flexibility at both ends. It can automatically split the payment between the two channels, send the two parts separately, and Bob’s client can recombine them.

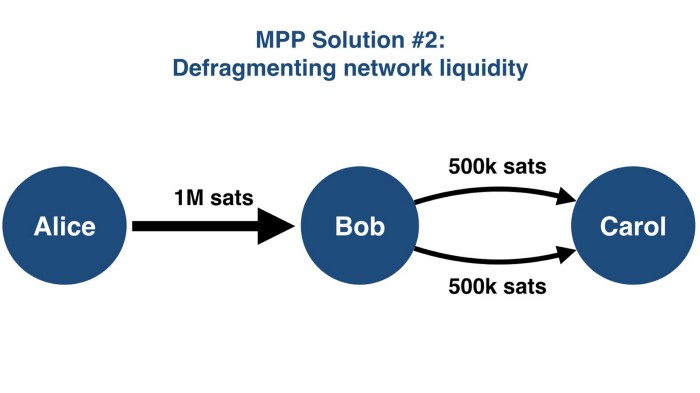

Second, let’s suppose Alice wants to send 1M sats to Carol. She doesn’t share a channel with Carol, but who cares? It’s a network. She has 1M sats on her channel with Bob all ready to send. Bob shares two channels with Carol, but tragically, he only has 500k sats on each. Without MPPs, the maximum transfer size is limited by the lowest local balance along the route. So if Bob only has 500k sats in any given channel with Carol, that limit applies to Alice too. Like with any liquid, the flow rate is limited by the narrowest pipe along the route.

MPPs effectively “defragment” the liquidity between Bob and Carol. Instead of being limited by the narrowest pipe, the flow is limited by the sum of pipes along the route. It combines those fragments into a greater, more useful whole. Since the sum of local balances between Bob and Carol is 1M sats, the constraint on Alice has vanished.

Instead of being limited by the lowest local balance of any channel along the route, payment size is now limited by the least total liquidity of any node along the route. The key restriction is now how much bitcoin is in the sender’s Lightning wallet, which makes perfect sense.

The effects at the network level are at least as momentous. Instead of each possible route being a stream of liquidity with a maximum capacity, like a water pipe, each node becomes its own little pool of liquidity. Channel capacities are no longer discrete; they’re additive.

Now imagine MPPs and Wumbos combined. Pools connected by channels of unlimited capacity aren’t pools any more. They’re not even lakes. It’s a single, vast ocean. No fragmentation, no obstacles, pure liquidity, optimal flow.

Breez & MPPs

Since we strive to eliminate all of Lightning’s seams and MPPs bring us one step closer to a seamless network, we immediately saw their utility and began implementing them. The client already receives MPPs automatically.

Advanced users can already open multiple channels to increase their capacity. However, Breez doesn’t yet support sending MPPs. Doing so is in the works for the next major update. We’re also working to simplify the process of creating multiple channels, and further improvements are coming soon. MPP is too good not to use, so we’re integrating it deeply into the Breez DNA.

Lightning over a sea of liquidity. And what causes those waves? The Breez, of course. (Image: pxfuel)

The coevolution of Lightning technologies

As any rabbit in the forest, pandemic survivor, or evolutionary biologist can tell you, the most important selective pressure on any species is the other species with which it comes into contact. The utility of any biological function or physiological feature — running, swimming, digesting pine needles, gills, wings, and big brains — depends on what other creatures are around, and what functions and features they have developed. Nothing evolves in a vacuum.

The same applies to the evolution of Lightning technologies. The utility of Wumbo channels fosters the proliferation of routing nodes and increasing payment sizes. But developments on trunk channels don’t serve much purpose unless the UX improves, attracting users and their liquidity. MPPs defragment the network’s liquidity and increase transaction volumes, necessitating Wumbos, which allow for still greater volumes over more channels, which makes life still easier for users …

The technologies we use evolve together, symbiotically, reinforcing each other, creating new niches, new opportunities, and new challenges. And like any evolutionary process, the best innovations of each generation will constitute the foundations for their successors. Lightning can’t help but improve. We just have to keep at it.