WORDS is a monthly journal of Bitcoin commentary. For the uninitiated, getting up to speed on Bitcoin can seem daunting. Content is scattered across the internet, in some cases behind paywalls, and content has been lost forever. That’s why we made this journal, to preserve and further the understanding of Bitcoin.

WORDS is a monthly journal of Bitcoin commentary. For the uninitiated, getting up to speed on Bitcoin can seem daunting. Content is scattered across the internet, in some cases behind paywalls, and content has been lost forever. That’s why we made this journal, to preserve and further the understanding of Bitcoin.

Donate & Download the February 2020 Journal PDF

Remember, if you see something, say something. Send us your favorite Bitcoin commentary.

Money is about credibly representing value transactions

By acrual

Posted February 5, 2020

According to the Selfish Gene book, we only want to exchange value or cooperate with strangers when there is an inmediate exchange. If we postpone this exchange, we are very likely to cheat (and even in the case we are not strangers!).

We are some serious cheaters according to this fascinating book and I agree.

Unless you believe we prefer to satisfy everyone else’s needs before our own, you must necessarily agree with this book, and this is important, because it explains money very well.

If you can’t give me something I value right now (barter), I want you to prove to me that you have provided value to someone else in the past, that is, I need a prove from you that you have made a value transaction earlier.

You must, as a result, be able to represent a transaction credibly.

What would you do if you had to represent a transaction in the most “credible” way 20.000 years ago?

I suggest that if you want to cooperate with me, whenever you provide value, you get in return something that is universally very scarce, so that you can’t tamper this representation easily. Otherwise I may have the feeling that you could be cheating me and again, you and I are very likely to do so.

But that something has to be easily recognizable by me, otherwise I won’t accept it either. If you want me to accept it, you’d better get divisible items, so that you can pay me smaller values. And chances are you will only accept stuff that is cheap and easy to transport. (in Menger terms, saleable in space and scale)

If I were you, I’d only accept stuff that is extremely cheap to store, that deteriorates the least over time, because you have no idea when your needs will arise, and that could be a long time into the future. (saleable in time)

Transferring the property of this stone must not depend on third parties, because otherwise those third parties are likely to cheat as well!!

During the first transactions, you will have no way of knowing if you are representing that transaction with the right-sized stone. It may be too big or too small. You won’t have any guarantees that the rest of humanity will accept this stone and as a result, you won’t be able to size it properly until this item is universally accepted by the market so that you can compare it. You’ll be gambling and speculating that you are sizing this transaction accurately. If it costs little to store, you will try to store as much as possible of it and as a result your gamble will have little cost.

Therefore that stone will be for you both a product you will use (a medium of exchange) and speculation too.

The market will slowly realize that by being data and software, Bitcoin is “the thing” that best solves each and everyone of these requirements.

The market should also understand that things that are valued are those which are stored, not those which are used because using them means buying and selling, so supply is kept high.

Storing means buying and keeping, limiting supply as a result. If Picassos were not kept, just seen in your home and then sold next day, then their value would tend to zero, but no, they are typically kept for decades.

Even if your shitcoin is designed to cure malaria, chances are that you will sell it inmediately after being used and as a result its value will tend to zero. With a value tending to zero, it is more likely that developers will end up curing malaria with Bitcoin than with your shitcoin.

For the n-th time, block, mute everyone speaking about shitcoins/blockchains, we have to be merciless with people that insist on being either ignorants or scammers.

Small note on Statism vs Libertarianism

I got into Bitcoin with a completely statist mindset, but understanding that we are programmed to cheat made me wonder if it does make any sense to pretend that Statism is the best way to organize ourselves.

It is also hard as a result for me to take seriously people that say they understand Bitcoin, and keep defending Statist views.

If we are programmed to cheat, and throughout history we have gone through the pain of using all sorts of monies in every single civilization as a way of solving it, does it make sense to spend each others resources in something named “common good”?

Tweetstorm Bitcoin as super-collateral

By Aaron (Fiat Minimalist)

Posted February 5, 2020

Bitcoin is quickly evolving into an asset that will become the ultimate form of collateral. Have been hearing more trad funds/groups willing to accept BTC as collateral in return for fiat loans at ~6-12% per annum

The latest I know of is a traditional global multi-family office that specializes in share-backed loans, and now have just branched out to BTC-backed loans.

Typical collateralized assets in today’s markets are (1) real estate, (2) shares, (3) bonds

As bitcoin continues to capitalize, its vol will approach & fall in-line with these categories of assets + liquidity will exceed even the most liquid shares (and BTC loans will become the cheapest, fueling more demand for BTC as the highest quality collateral) -> reflexivity

With the exception of volatility, Bitcoin scores (or will soon score) better than all other assets in all “what makes a good collateral” dimensions such as liquidity/marketability, 24/7 availability, speed and ease of settlement, global acceptance, fungibility etc.

Unlike most assets, Bitcoin is a bearer asset so its clearly unencumbered. Once lender is holding on to the actual BTC they can be sure it hasn’t been pledged to 10 other parties simultaneously

Also cheaper & more efficient than paying for title deed searches, lien enforcement

BTC can be liquidated 24/7 and almost immediately - unlike real estate which can sometimes take >1 year for resolution, or shares/bonds which only trades certain times during the day for which liquidity tends to dry up during periods of stress

Matter of time banks begin accepting Bitcoin as collateral, and they’ll have to build out infrastructure to manage Bitcoin borrowing/lending

Lessons from the uneven distribution of capital

By Nic Carter

Posted February 8, 2020

What we can learn from distorted maps

As the crypto markets continue their transition from a retail-focused, unrestricted global altcoin casino, to a more constrained and regulated environment, it’s worth zooming out and pondering what long-term allocative outcomes this market is likely to witness. Cryptocurrency purports to allow commerce and capital to flow freely, independent of artificial nation state boundaries. However, when securities are involved, the state tends to intervene.

There is a good reason for this: securities are high-stakes markets governing the allocation of productive capital, and for them to function, the state needs to enforce fairness, disclosure, and information symmetry. In fact, the best example in favor of securities laws I can think of is the anarchy and carnage exhibited in the Initial Coin Offering boom in 2017. If blockchain-lubricated capital markets mature from these early hiccups and some of these equity-like assets become viable, they will surely be indexed to their local jurisdictional rules. To the extent that tokenization and crypto-wrapped securities become investable, I’d venture that the U.S. is strongly positioned to compete for issuers — despite the globalized nature of the crypto industry.

What distorted maps tell us about shareholder rights

It’s often said that the SEC is “pushing innovation abroad” by cracking down on crypto projects, especially those that issue pseudo-equity in the form of a token. This may well be the case. It is also quite a reductive view. Capital clusters in jurisdictions where the rules are understood, where property rights are respected, and where legal systems appropriately apportion power between shareholders and directors. Thus, the enforcement of age-old rules which made the U.S. the most vibrant equity market on earth in a crypto context can be understood as either hostile to issuers, or accommodating to investors. The latter perspective is sorely neglected in the regulatory analysis.

In the issuance of equity, standardization is a godsend. If you work in startups, you will mostly likely have a strong understanding of the nuances of a Delaware C corp or the YC SAFE. When issuers select these instruments to raise capital, they are opting for a set of rules and a legal context which are mutually understood by founders, VCs, and law firms. This often entails cheaper diligence and less legal overhead. Indeed, some VC funds don’t invest in anything other than Delaware C Corps. This is just one anecdote, but it hints at the bigger picture: investors like predictable and comprehensible structures. They like to know where they stand relative to founders, and what their recourse is if something goes wrong. At a global scale, small differences in jurisdictional predictability lead to wildly divergent outcomes.

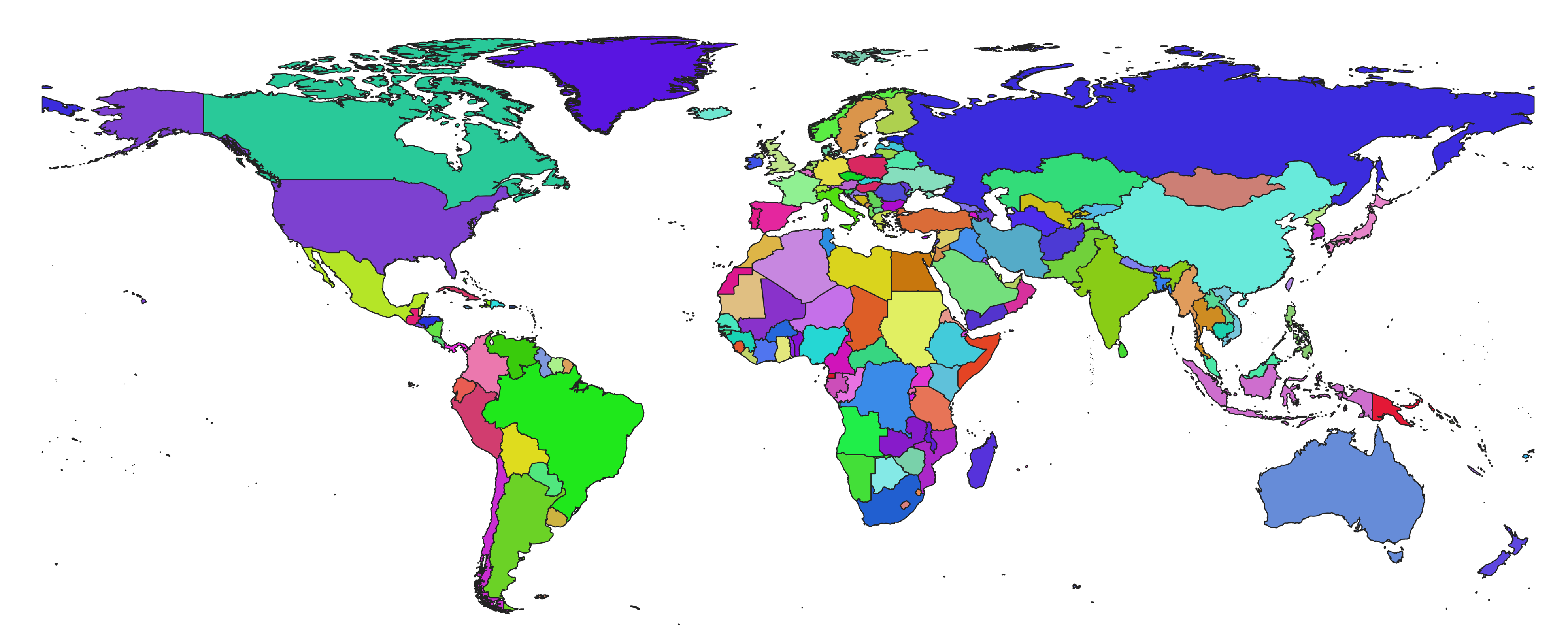

You may be surprised to learn that the U.S. accounts for 26% of global GDP, but a staggering 40% of global public equity capitalization. This point is best made visually with a chart called a cartogram. What a cartogram does is weight land area by some variable while keeping shape intact (or at least attempting to). Let’s start with a basic map projection. In this case I am using the Plate Carée projection, a variant of the equirectangular projection. This is what it looks like:

World countries shapefile courtesy of ArcGIS Hub (source)

World countries shapefile courtesy of ArcGIS Hub (source)

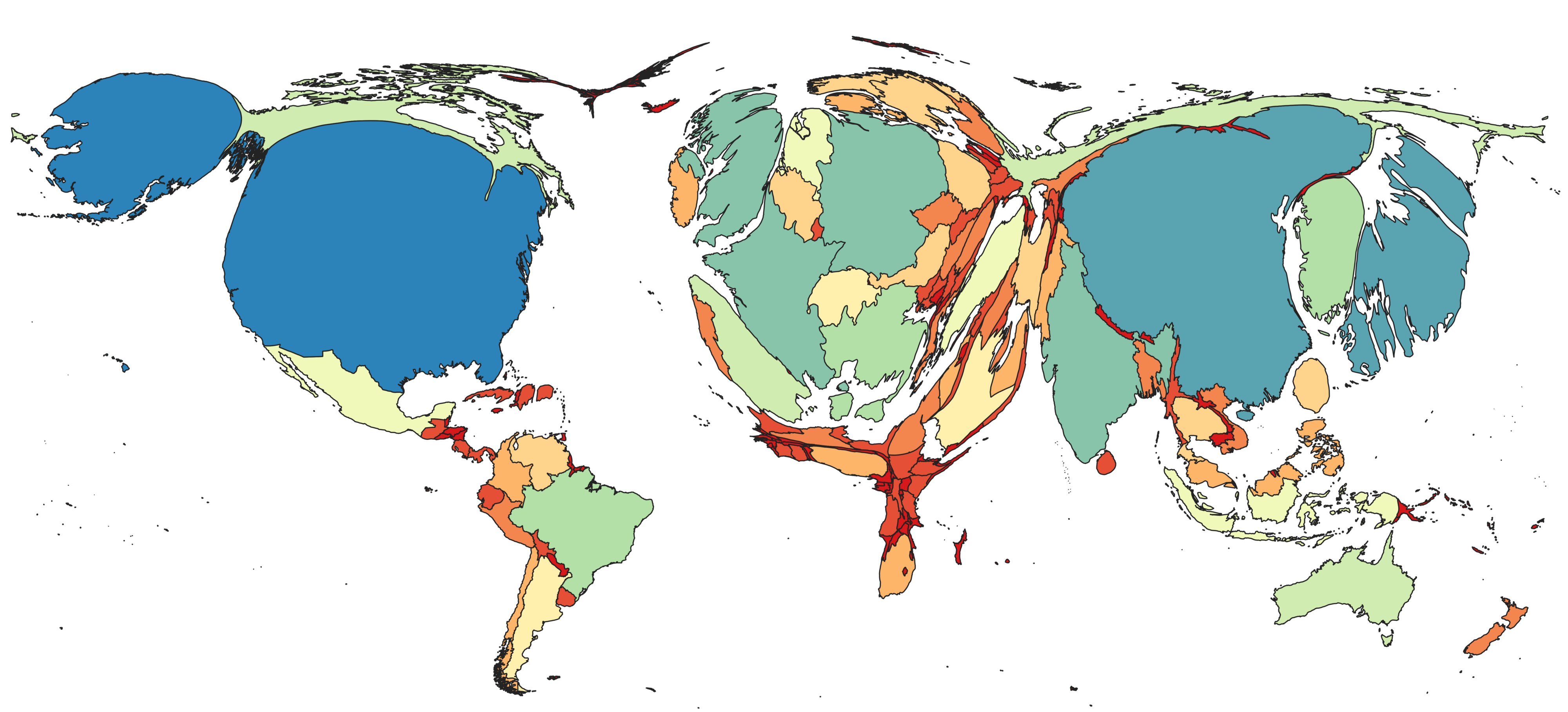

Now let’s weight countries by GDP (2018) so you can get a general sense of the global income distribution. This means that certain more developed countries will swell up and less developed countries will shrink. But I’ll do my best to retain the general shapes of the countries so the map is still intelligible.

Cartogram made with Scapetoad and visualized in QGIS3.4. Data is 2018 GDP in USD terms from the World Bank

Cartogram made with Scapetoad and visualized in QGIS3.4. Data is 2018 GDP in USD terms from the World Bank

I’ve bucketed countries into a few color coded categories so you can compare similar countries by GDP. For instance, with this chart, you can tell that France ($2.5T), Germany ($3.6T), and India ($2.9T) are in a similar range. Same with South Korea ($2T), Brazil ($2T), and Italy ($1.9T). You can also tell that Australia, Spain, Canada, and Russia have similar GDP — between $1.3 and $1.6 trillion. You get the point.

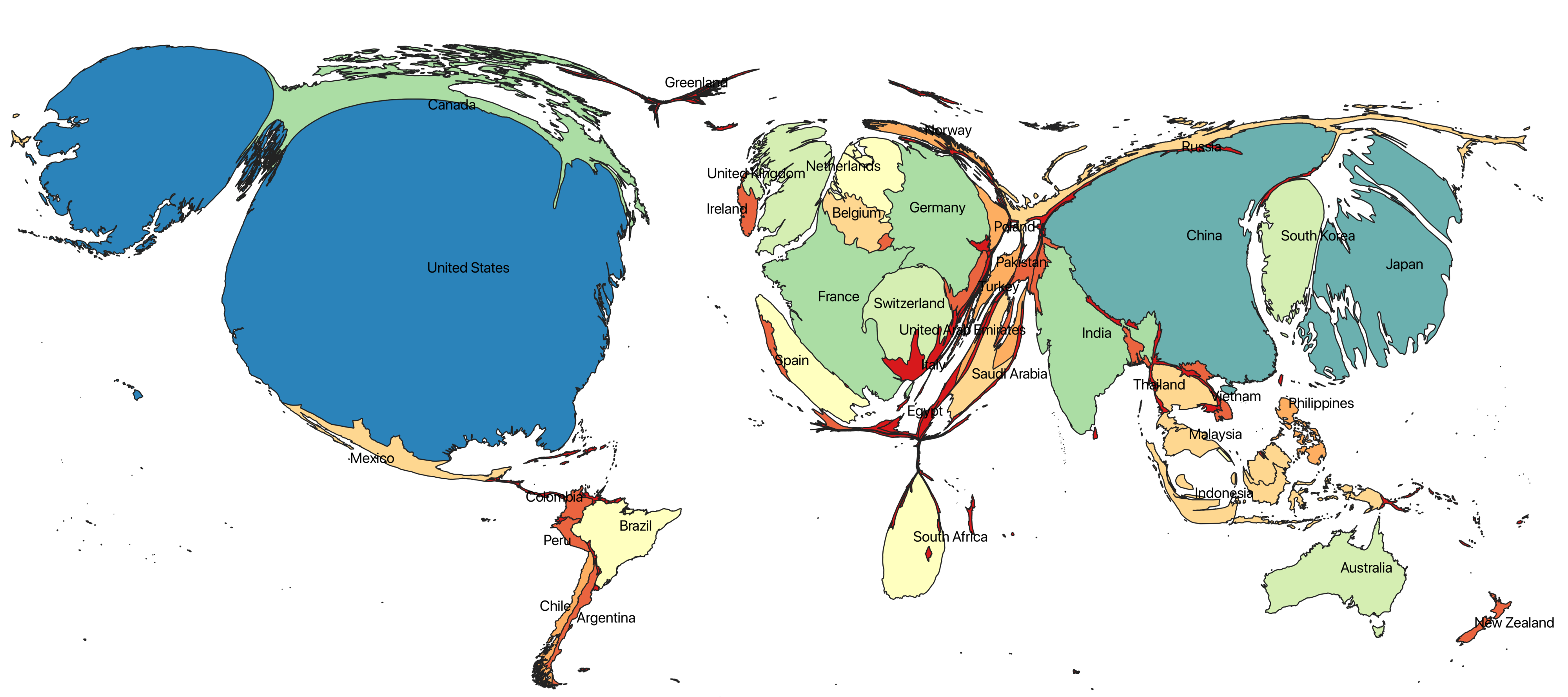

Now if I were to ask you what the same map with domestic public equity capitalization as the key variable might look like, you might imagine it would resemble the above. More GDP, more money to invest in the stock market, after all. Interestingly, this isn’t quite the case. Here’s the map weighted by the size of domestically listed equity markets:

Cartogram weighted by market capitalization of domestically listed companies, 2018 data courtesy of the World Bank

Cartogram weighted by market capitalization of domestically listed companies, 2018 data courtesy of the World Bank

Please note that Hong Kong isn’t present on this map because it sadly wasn’t included in the open source vector file I used to build the country shapes. Hong Kong would be about 50% the size of China on this map. Compare the Public Equity cartogram with the GDP cartogram and you notice a few things immediately:

- the U.S., even though generates a big chunk of global GDP, still punches above its weight in terms of domestically listed equity

- South America and Africa have under-developed capital markets, even relative to GDP

- Chinese equity markets are prominent, but small relative to their share of global GDP

- niche/haven jurisdictions like Hong Kong (not depicted), Luxembourg, Singapore, Switzerland, are overweighted

- Europe represents a significant fraction of equity markets but less than you might expect from their share of global GDP

Let’s dig in to the data a bit more to find the biggest outliers when it comes to countries that punch above their weight from an equity market perspective.

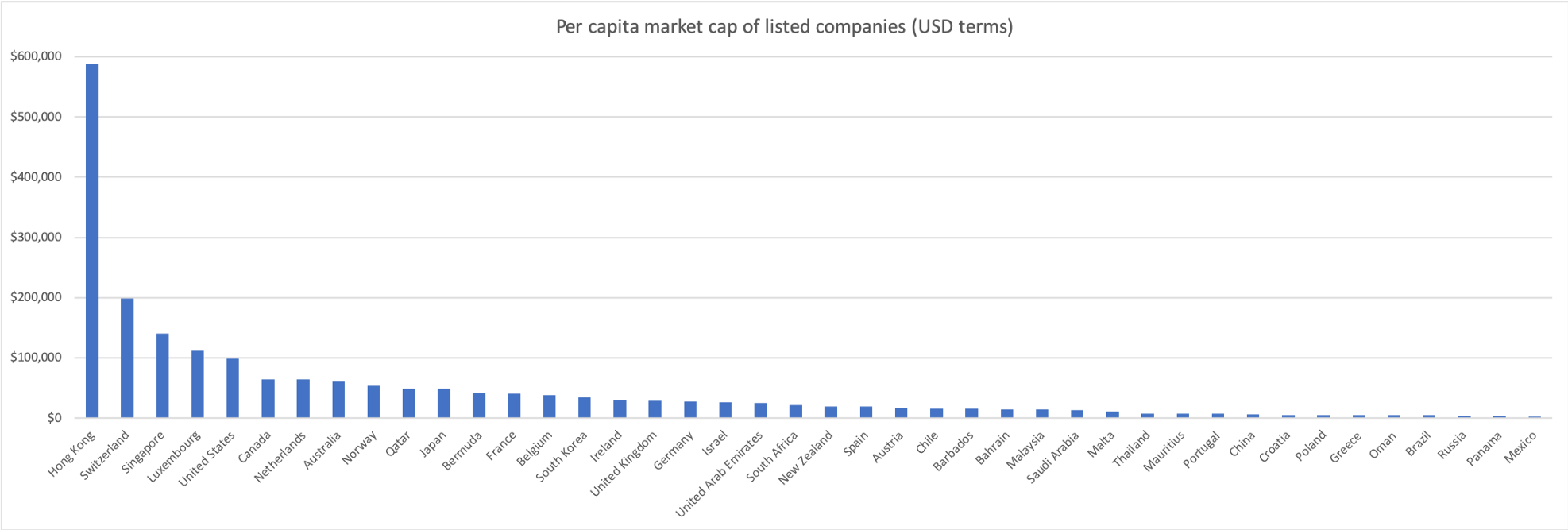

Market capitalization of listed domestic companies (USD) divided by population, World Bank data

Market capitalization of listed domestic companies (USD) divided by population, World Bank data

Amazingly, the per capita market cap of domestic equity in Hong Kong is US$588k. This is a bit of an exception, as many Chinese companies choose to list on the HKEX rather than in Shanghai or Shenzhen. This is partially a function of less onerous listing requirements in Hong Kong, partly a function of Hong Kong’s financial hub status, and tighter relationships with western capital markets, and partially a function of the fact that Hong Kong’s legislature, judiciary, and attitude towards property rights are influenced by its former status as a British colony.

For a more detailed take on why Chinese firms are so fond of listing in Hong Kong, Fanpeng Meng’s A History of Chinese Companies Listing in Hong Kong and Its Implications for the Futureprovides additional context:

Specifically, there are some fundamental elements [present in Hong Kong]: a stable and sound legal system with strong respect of private property ownership, an absence of exchange rate control with the linked exchange rate, an efficient and sophisticated banking sector populated by some of the world’s top banks, a simple and low-rate taxation regime in which there are no capital gains taxes and whereby income taxes are charged on a territoriality basis, and a relatively clean and transparent business environment intensively monitored by the government.

Listings in Hong Kong are quite significant relative to China, totaling about US$4.3T compared with China’s US$8.7T.

Other states scoring highly on the per capita equity market cap figures include a smattering of haven states like Switzerland, Singapore, Bermuda, and Luxembourg, and developed nations like the U.S., Canada, the Netherlands, Norway, and Japan. Regional financial hubs like Qatar, the UAE, and South Africa also score well by this measure.

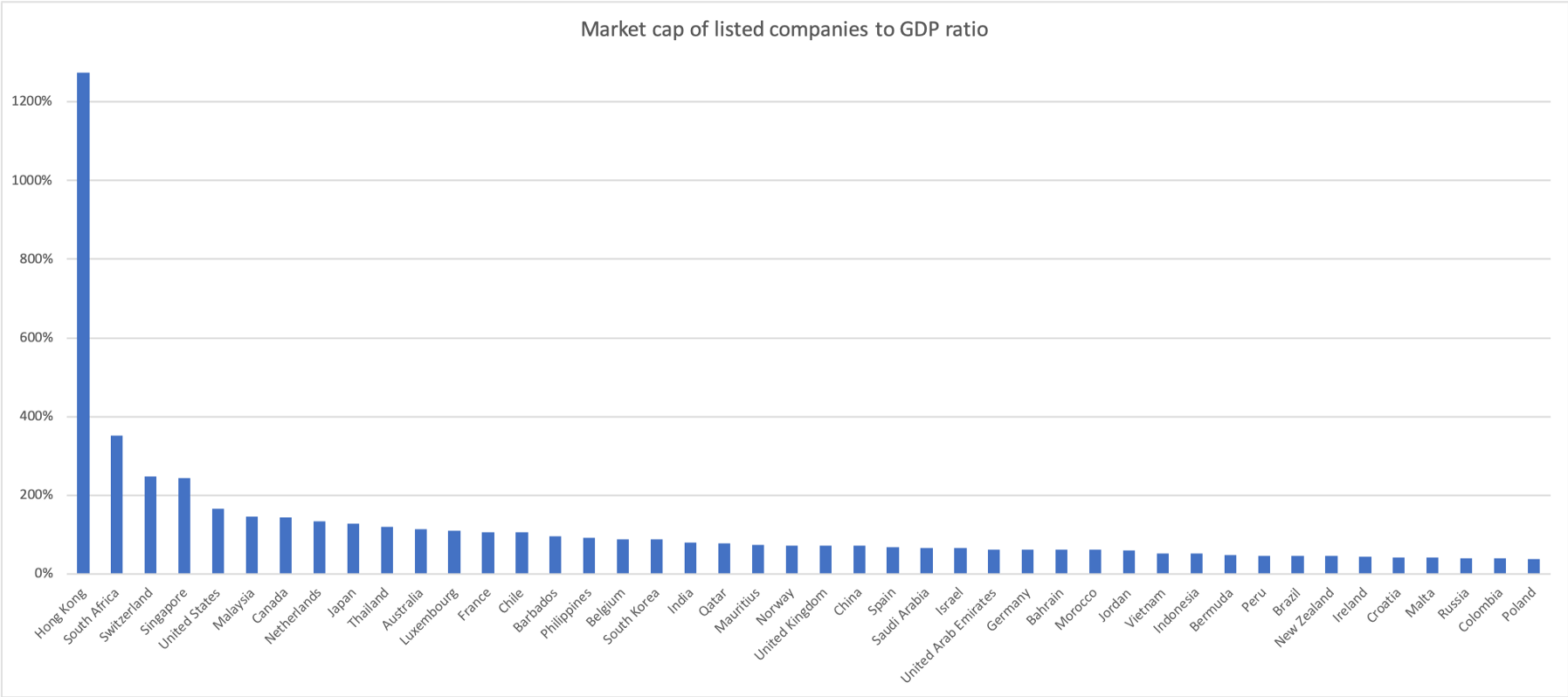

Another similar measure is the aggregate market cap to GDP ratio. This synthesizes the two cartograms depicted above, so you can find the biggest outliers without having to visually inspect the charts.

The ratio of the market capitalization of listed domestic companies (USD) to 2018 GDP, World Bank data

The ratio of the market capitalization of listed domestic companies (USD) to 2018 GDP, World Bank data

Compared with the per-capita metric, this one better selects for nations which have a lower overall standard of development but still have large equity markets relative to their economies. Again, Hong Kong is the stark outlier here. But it’s joined in the list of unexpectedly large equity markets by places like South Africa, Malaysia, Thailand, and Chile.

South Africa is an interesting case study. In Africa, there are only three meaningfully developed local equity markets — Nigeria, South Africa, and Egypt. South Africa, a historically prosperous former British colony with the lingering presence of British institutions, is the largest of the three. Literature on equity development in Sub-Saharan Africa is sparse.

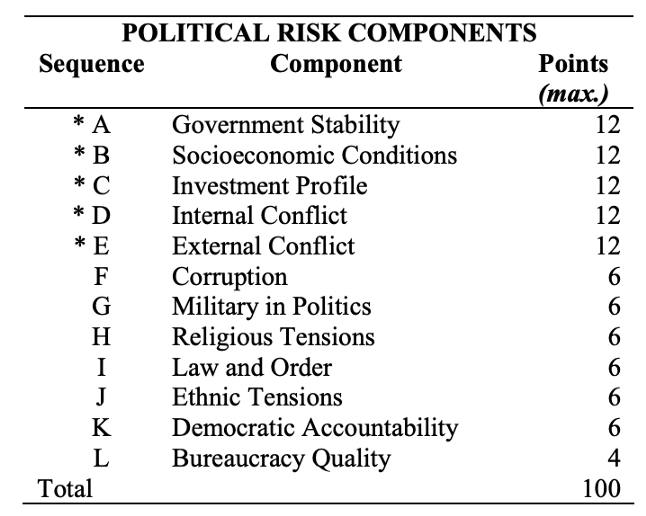

Political risk determinants from the International Country Risk Guide Methodology

Political risk determinants from the International Country Risk Guide Methodology

Some answers can be found in an IMF working paper on the topic (Andrianaivo and Yartey 2009). The authors conclude from a cross sectional regression that the most important determinant of equity market development in Africa, aside from straightforward variables like domestic savings and per capita GDP, is political risk. This stands to reason: if a military junta takes over, or parliament is dissolved, or the country experiences armed insurrection, equity markets will not develop. I’ve inserted the political risk rubric that the authors used to give you an idea of the relevant criteria. Historically, South Africa has been relatively conflict free (their main post-independence conflicts were minor excursions in Namibia and Angola) and has benefited from stable rule under the ANC, although political conditions have deteriorated in recent years.

My main reaction from the data is to observe that the development of a vibrant equity market is somewhat of an aberration. There are a huge number of disqualifying features — and indeed, your typical state does not in fact have a liquid domestic equity market. So what explains the uneven development of public equity markets around the world?

Rules Make the Market

So why do some jurisdictions dominate when it comes to the issuance of public equity? As it turns out, there’s an incredibly vibrant literature motivated by this specific question. The foundational, field-defining paper is Law and Finance by La Porta, Lopez-de-Silane, Shleifer, and Vishny.

If you haven’t read it, I strongly recommend a read. It’s one of my favorite economics papers, because the methodology really is dead simple: the authors simply look at the variance in investor protections across a broad array of countries, and realize that legal traditions in those countries explain a significant fraction of that variance. In other words, the legal tradition employed on a country-by-country basis, which informs_ what it means to be a shareholder._

Specifically, the authors divide commercial legal traditions in 49 jurisdictions into civil law and common law, further subdividing civil law into German, French, and Scandinavian variants. Common law refers to the British tradition of allowing judges to shape the law through precedent, whereas in civil law, inherited from the Roman tradition, the law is generally created by the legislature, with case law (precedent-setting through court cases) being secondary.

As the authors (henceforth LLSV) note,

[Civil law] originates in Roman law, uses statutes and comprehensive codes as a primary means of ordering legal material, and relies heavily on legal scholars to ascertain and formulate its rules

More abstractly, you can think of common law as a bottom-up, adaptive approach, and civil law as a top-down, more rigid approach. The consequential differences between jurisdictions with diverging legal traditions are significant; indeed, it has been compellingly argued that Brexit primarily boils down to a dispute between legal traditions (in which the EU attempted to impose a civil law tradition on the common law UK, causing frictions). In the words of the Economist, “English lawyers take pride in the flexibility of their [common law] system, because it can quickly adapt to circumstance without the need for Parliament to enact legislation.” In short, common law is considered to be faster moving and more adaptable — ideal for fast-changing capital markets.

A full 21 countries in the sample inherit France’s civil law tradition, many of which were conquered by Napoleon. Others were added as part of France’s colonial holdings in Africa and the Pacific. And French jurisprudence informed the structure of post-colonial regimes in the wake of Spanish and Portuguese empires in Latin America.

The British Empire led to the proliferation of English jurisprudence throughout the commonwealth. Strikingly, these colonial origins seem to have had long term effects on the future development of shareholder rights, hundreds of years later. As LLSV note:

[L]aws differ a great deal across countries: an investor in France has very different legal rights than she does in Britain or Taiwan. Moreover, a large part of this variation is accounted for by differences in legal origin. Civil laws give investors weaker legal rights than common laws do. The most striking difference is between common law countries, which give both shareholders and creditors the — relatively speaking — strongest protections, and French civil law countries, which protect investors the least.

Mechanically, LLSV enumerate specific shareholder rights which speak to the extent to which shareholders are protected against directors. A selection are listed below:

- One share one vote: whether laws exist to tie shares to votes, as opposed to dual classes or nonvoting tranches of equity. The authors consider jurisdictions with these laws as more shareholder friendly

- Proxy by mail: whether or not shareholders are allowed to vote by mail (more hindrance in shareholder votes disempowers shareholders, especially smaller ones)

- Oppressed minorities mechanism: whether or not minority shareholders (owning 10% or less of share capital) have the ability to challenge the decisions of management or force a buyout of their shares in the case of certain changes like M&A activity

- Preemptive rights: whether shareholders have the right of first refusal over new equity issuance

- Percent of capital required to call a shareholder’s meeting: the higher the required fraction, the less friendly the jurisdiction is to minority shareholders

Their conclusions, while simple from a statistical perspective, were revelatory in the corporate governance literature. LLSV found that:

[A]long a variety of dimensions, common-law countries afford the best legal protections to shareholders. They most frequently (39 percent) allow shareholders to vote by mail, they never block shares for shareholder meetings, they have the highest (94 percent) incidence of laws protecting oppressed minorities, and they generally require relatively little share capital (9 percent) to call an extraordinary shareholder meeting. The only dimension on which common-law countries are not especially protective is the preemptive right to new share issues (44 percent). Still, the common-law countries have the highest average antidirector rights score (4.00) of all legal families. Many of the differences between common-law and civil-law countries are statistically significant. In short, relative to the rest of the world, common-law countries have a package of laws most protective of shareholders.

Taking the analysis further, the same four authors followed their seminal paper with the 1997 Legal Determinants of External Finance, demonstrating that not only do common law countries systematically offer better shareholder protections, but that these investor protections empirically manifest in larger and more robust capital markets.

The authors summarize the key finding:

[T]he legal environment — as described by both legal rules and their enforcement — matters for the size and extent of a country’s capital markets. Because a good legal environment protects the potential financiers against expropriation by entrepreneurs, it raises their willingness to surrender funds in exchange for securities, and hence expands the scope of capital markets.

This might seem like a simple point — more investor assurances yield more capital deployed, but when you reflect on the fact that these assurances trace back to the legal philosophy undergirding the financial system, one becomes starkly aware of the path dependence in capital market outcomes. Put simply: institutional quality dictates allocative outcomes. The U.S. isn’t just the largest hub of capital formation on earth, it’s disproportionately large. This system creates extreme outliers like Hong Kong, Singapore, or Luxembourg.

A related conclusion can be found in Hernando de Soto’s book, The Mystery of Capital. De Soto evaluates the relationship between property rights and capitalism in a large number of countries worldwide, and concludes that for capitalism to function properly, it must rest atop the bedrock of strongly codified property rights. His reasoning is as follows: the main form of savings for individuals worldwide is through property (in particular, real estate). The main way that capital formation occurs on a small scale is through the monetization of that property, turning it from a purely instrumental asset (somewhere to live) into a capital asset. One example of this would be an individual borrowing against their house in order to set up a small business. If lots of savers can mobilize the capital that they naturally accumulate, capitalism can flourish.

However, as de Soto finds, a significant chunk of property, especially in the developing world, is poorly codified. That is to say, homeowners cannot prove that they hold the deed to their home (a deed may not exist), and they may not have a plausible path to formalizing their ownership. This inhibits their ability to monetize their property at all. Typically, this is due to a dysfunctional bureaucracy or a state apparatus which does not provide a means for incorporating black/grey markets into the formal economy. My takeaway from this remarkable book is that free market economies alone are not enough; they must be accompanied by a legal and bureaucratic apparatus which is flexible enough to enable property owners to make transition from de facto to de jure, and these rights must be consistently respected. For a longer take on De Soto’s conclusions as applied to Bitcoin, see Allen Farrington’s essay on the topic.

Cryptocurrencies, perhaps more so than any asset, mitigate these institutional constraints. It’s trivial to prove to a third party that you own some Bitcoin; it’s trivial to self-custody this claim, and settlement is physical and almost immediately final. Cryptocurrencies are monetary institutions — the protocol lays out a set of rules for permitted behavior, and all participants must adhere to them. This is what gives cryptocurrencies such remarkable global penetration: users mutually understand where they stand relative to the system and the established ruleset, and trust that no well-connected lobbyists are able to exert local policy on system. This is what Nick Szabo refers to as social scalability — the idea that a system can only scale to serve millions of disparate users if it standardizes behavior in a narrow domain (say, rules for what transactions are valid) while minimizing idiosyncrasy and obscurity (which undermine the system’s credibility).

Don’t Count the U.S. Out

Within the crypto industry, the U.S. has a reputation for being extremely restrictive with regards to the issuance of new cryptoassets. Since 2017 with the infamous DAO report, the SEC has made it quite clear that ICOs are more often than not unregistered securities issuances, and that issuers should be held to the same standard as conventional issuers of securities. In the U.S., if you want to sell equity to the general public, this entails significant legal costs and a high standard of transparency.

In the crypto markets so far, virtually no issuers have met this conventional standard (one exception is Blockstack). Moreover, it’s not even clear what information would be considered material for the issuance of a novel protocol or token. In their paper _What Should Be Disclosed in an Initial Coin Offering?, _Brummer, Kiviat, and Massari convincingly make the case that the various disclosure frameworks in the U.S. poorly fit the reality of token issuance, calling for a more appropriate model to be devised.

The significant amount of teeth-gnashing within the crypto industry belies the reality of these markets: the vast majority of tokens sold to the public were entirely meritless, and carried no investor protections whatsoever. Even in cases where tokens purportedly held benefits relative to conventional issuance, with touted features like algorithmically enforced vesting schedules, much of the time these soft provisions were not actually enforced. Hoffman’s _Regulating Initial Coin Offerings _takes a careful look at the promises made by promoters which could have been algorithmically enforced. In a survey of the top 50 ICOs that raised significant capital in 2017, Hoffman evaluates the actual implementation in code of promises made to investors. These fall into three categories:

- Promises made about the restriction of supply

- Promises made about vesting schedules that team members were subject to and restrictions on transfers

- Promises about surrendering power to modify smart contracts once deployed (many issuers claimed they would ultimately give up this power)

Unsurprisingly, the authors, by examining the actual code written by issuers, find overwhelming noncompliance with these relatively weak restrictions. So not only were issuers providing extremely limited assurances to buyers; those issuers could not even adhere to their own, self-imposed standards!

So we have a situation where the vast, vast majority of token offerings openly flouted the law. And _lex cryptographia _was an inferior substitute for the law: the few assurances which could indeed be encoded into a smart contract were only spottily upheld. In this context, U.S. policy towards token issuance seems downright reasonable. Assuming that the predominant legal analysis of token launches (in which a single issuer sells tokens to the public) as unregistered securities is correct, the fact that this issuance was happening through a new technological medium is irrelevant.

If you strip away the technobabble and the (generally spurious) claims of “decentralization” and “unstoppable applications,” you are left with the straightforward issuance of pseudo-equity to the general public. That anyone, even the most devoted crypto stalwarts, imagined securities regulators would turn a blind eye to this practice in perpetuity is baffling. And gradually, the SEC has come to reckon with this market niche. By being relatively (but not overly) stern, U.S. regulators are positioning themselves for a middle path. Far from outright banning tokens and the industry surrounding them, regulators have meted out a mixture of punishments. The SEC has prosecuted the very worst ICOs and given amnesty to others. Some academics have even praised the much-maligned SEC strategy of selectively enforcing the law.

Reminding ourselves that the U.S. has a 40% share of public equity markets for a reason, the professed strategy of many industry participants to seek greener pastures elsewhere seems short-sighted. The fact that an inferior instrument (the public ICO) did not get a regulatory blessing does not mean that the U.S. is destined to lose its crown as the premier locale for capital formation. Indeed, many high profile securities regulators in other capital-friendly jurisdictions are falling into step with the U.S., as is customary. If crypto issuance is to evolve into something friendlier to buyers, with functional, germane disclosures, genuine algorithmically-enforced vesting and lockups, and perhaps other strongly codified investor protections, there’s no reason that regulators wouldn’t acknowledge this reality. That they haven’t given carte blanche to these issuances is a reflection on the poverty of the implementations we’ve seen so far, not the weakness of the idea.

Recall, given the above, why the U.S. hosts a disproportionate share of public equity capital. Not only has the U.S. been a hegemonic power for most of the last century, but it has been politically stable, has not seen violent conflicts on its shores, and it boasts an accommodating common law regime which has manifested in strong shareholder protections. Additionally, it has a large middle class for which investing in equities is as much as pastime as it is a necessity. This affinity for active consumer participation in capital markets has unsurprisingly spilled over into crypto as well. Coinbase, the largest crypto exchange/custodian in the world (by far!), is an American company. The largest financialized Bitcoin product is the Bitcoin Investment Trust, issued by the NY-based Grayscale. The first established global financial institution to take Bitcoin and digital assets seriously was the Boston-based Fidelity. To the extent that this industry is an asset class (to be clear, the jury is still out on this!)_, _jurisdictions with the financial plumbing and the consumer demand for exposure will naturally be the first to service it.

This perspective may strike you as anglocentric. However, consider it in context. Within the crypto industry, the U.S. is considered a pariah simply for enforcing its local laws (and even then, extremely permissively — see the Block.one settlement). The token frenzy has been chased overseas for now, but it’s unlikely to develop into a functional securities market if it operates in an anarchic mode, dependent on the goodwill of marginal jurisdictions. The industry’s best hope is to acknowledge that market oversight is what makes them function and embrace a regime which takes a commonsense view about shareholder/tokenholder protection.

When and if these markets do mature, and security tokens, or on-chain cashflow-wrapped instruments, or highly automated smart-contract-mediated equity do emerge as a meaningful segment of the securities industry, I would fully expect U.S. regulators to engage productively. At that time, issuers and market participants will benefit from taking part in the most dynamic capital markets on earth.

The Tortoise and The Hare

By Marty Bent

Posted February 10, 2020

“Trust me.”

“Trust me.”

“I want to be candid. This strategy will cost money, involve risk and take time. We will have to try things that we’ve never tried before. We will make mistakes. We will go through periods in which things get worse and progress is uneven or interrupted.” — Timothy Geithner

This is but one snippet of one iteration of the pitch newly appointed Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner shilled to the public on February 10th, 2009.

At the time, he was frantically running across Washington D.C., from Capitol Hill to media appearance after media appearance in an attempt to convince his fellow citizens that $300 Billion of the remaining TARP funds he was about to spend on toxic assets was not a bad deal. The populace was wary that the banks he would be buying the toxic assets from would refuse to sell below market price. They had been through a lot at this point.

As Geithner was uttering the words quoted above, the computers running bitcoind v0.1.5 and below were racing to confirm the 3,768th block of the Bitcoin blockchain. Ordering their CPUs to go out and seek a SHA-256 hash below the difficulty target at the time so that they could collect 50 bitcoin block subsidy.

No one really noticed it then, but there were two solutions to the Great Recession running in parallel; the one put forth by Timothy Geithner, Ben Bernanke and crew, and another put forth by Satoshi Nakamoto.

The powers that be in the US and across the globe - those attempting to put Humpty Dumpty back together again - were too busy to be cognizant of their competition in the aftermath of the financial crisis. They were rushing to make sure people would be able to get cash out of ATMs. Satoshi and the band of misfits who were drawn to the new open source protocol he launched were hyper aware of their competition. This is evidenced by the message that was etched into Bitcoin’s genesis block, “The Times 03/Jan/2009 Chancellor on brink of second bailout for banks”. A reference to a headline in that day’s issue of The Times of London.

This wasn’t the only reference to the traditional monetary system that would be made by Bitcoin’s creator. Coincidentally, on the day after Timothy Geithner was making quick iterations of his pitch to the American people Satoshi made a direct reference to the Central Banking system and its flaws in his eyes:

“The root problem with conventional currency is all the trust that’s required to make it work. The central bank must be trusted not to debase the currency, but the history of fiat currencies is full of breaches of that trust.” — Satoshi Nakamoto

Over the course of the last eleven years, the two solutions have been going head to head in the market. The solution put forth by Geithner and crew - who have bequeathed control of the levers to the Fed presidents and Treasury secretaries who have followed - is more of the same; money printing. The accumulation of long-term debt in hopes that we can stoke production today. On the surface, it seems to be working. But can this type of monetary policy persist?

The solution put forth by Satoshi is in direct opposition to the one put forth by the banking elite; a sound digital money that cannot be debased or controlled by a select few. Bitcoin is controlled by everyone and no one at the same time.

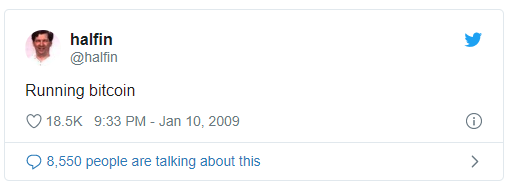

The first man to ever receive a bitcoin transaction. RIP Hal.

The first man to ever receive a bitcoin transaction. RIP Hal.

The two competing solutions are engaged in a classic Tortoise v. The Hare scenario.

The Federal Reserve and other Central Banks around the world have sprinted out of the gate; increasing the size of their monetary bases by orders of magnitude in very short order as they tinker with interest rates on a whim.

The Bitcoin Network has been on a slow grind for the last eleven years. Consistently producing blocks roughly every ten minutes as those who would like to see it succeed meticulously fortify the system. Working to make it more efficient, more scalable, more private and more robust one pull request at a time.

Most people don’t realize it, but we’re all watching a race to fix the money play out in real time. The money game is a long game. My sats are on the Tortoise.

Why Bitcoin is Not a Security

By Elisabeth Préfontaine

Posted February 10, 2020

Bitcoin is a broad topic and links together many disciplines such as cryptography, game theory, monetary theory, monetary history, economics, computer science, network dynamics, thermodynamics and information theory. This text shall be understood as a demonstration that Bitcoin, Bitcoin-related dealings, trading, and applications unequivocally sit outside the scope of the securities or derivatives legislation. This demonstration should make the case as to why the proposed framework for crypto-assets trading platform by the Consultation paper 21–402 and CSA Staff Notice 21–327 does not apply to Bitcoin.

1.1 Bitcoin Never was a Security

Here is a brief but straightforward explanation as to why Bitcoin was not a security from the start.

Monetary Capital

- No monetary capital was raised to develop Bitcoin.

- There was never a bitcoin Initial Coin Offering (ICO).

- There was no investment of capital from a founder.

- There was no premine (i.e. founders keeping a portion of the tokens for themselves).

- There is no bounty program, or free tokens offered to ‘’promoters’’.

- No capital was spent to promote its launch.

- Growth was entirely organic.

- Bitcoin was born out of an 8-page idea and roughly 40 years of R&D.

- The early-stage was sustained by volunteers.

- Bitcoin is not debt; Bitcoin is not equity. Bitcoin is Bitcoin.

Value

- Bitcoin is a bearer instrument. It solves for the double spending problem in the digital world.

- Bitcoin is functional since its inception and has an up time of 99.9837111434% since then.

- Bitcoin has no financial statements.

- Bitcoin doesn’t share security-like attributes such as a profit-sharing interest.

- The currency bitcoin has unique characteristics where individuals can express personal preference (see section 1.3)

- The market has spontaneously attributed value to it.

- The price is market driven. The value of one bitcoin is one bitcoin.

- The network effect of Bitcoin has value: its community, its users, its developers.

- The proof-of-work has value. It is an expensive monument of immutability.

- The stability at the base layer has value.

- The transparency and predictability of Bitcoin’s monetary policy has value.

- The self-regulating mechanism embedded in bitcoin has value.

- Bitcoin is its own and we are still early in the discovery of its full potential.

Decentralization

- Bitcoin is not a common enterprise. It is a network.

- Bitcoin is a decentralized system recording a sequence of transactions with 80,000+ nodes

- Bitcoin is not a company. There is no authority in charge, no management team, no CEO, no head office, no sales team, no tech support line.

- It is not centrally planned in an effort to deliver an eventual product. Bitcoin exists.

- No one person (or entity) controls the network or the protocol or can change the rules.

- No2X is a specific event that proved, in real life, bitcoin’s decentralization and uniqueness versus other centralized cryptocurrencies.

Unique Phenomenon

- A replica or a bitcoin 2.0 / 3.0 / 4.0 would inevitably be centrally planned.

- That central planning would most likely involve securities-like characteristics.

- Now that the path to creation is known a 51% attack could be successful in the early days

This section aimed to demonstrate that Bitcoin is not and never was a security. It is very possibly a one-time phenomenon and draws a line between bitcoin and the rest of so-called crypto-currencies.

We ended up with 2,000+ crypto-currencies because of the Blockchain bubble. A very sticky narrative has developed around the “technology underpinning bitcoin’’, as if it could be considered in isolation. The market created the name ‘blockchain’ which led to marketing narratives and fund-raising pitch decks being created. Much like the “snake-oil” claims of previous centuries, this new technology would solve almost any problem in the world (from lettuce tracking to identity management). This spurred the rise of blockchain projects raising capital through ICOs (initial coin offerings) in a tulip-bulb like mania.

We ended-up with 2000+ so-called crypto-currencies because very few took the time to first understand what, how and why bitcoin is. If organized true data without a central authority is not needed, then decentralization and open architecture are not needed. This would have helped contrast Bitcoin’s network and infrastructure with Initial Coin Offerings (ICOs) which are essentially a global venture-capital crowdfunding mechanism.

Could there be networks that initially started as an ICO and now are too far advanced and can no longer be considered a security? Perhaps. This will be a definition question that securities regulators will need to answer. But Bitcoin did not start as an ICO.

Understanding the uniqueness of Bitcoin’s conception and how it gave life to a digitally native scarce asset is perhaps the most direct way to comprehend what makes it different from a security-like instrument.

1.2 What is Bitcoin? Bitcoin is Text.

Bitcoin is surely different from anything we have seen before. Some argue that Bitcoin is a form of money, others argue it is a commodity and some simply don’t see anything in Bitcoin. However, this does not matter. What matters is Bitcoin exists and its network and protocol do exactly what they are meant to do, for over ten years. Bitcoin is text, information, speech. It communicates.

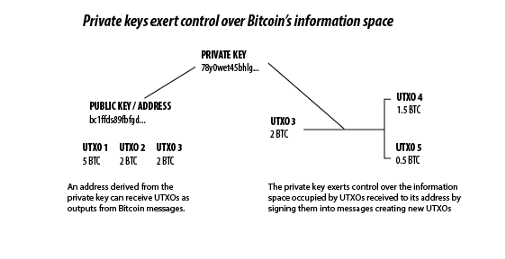

“Bitcoin is a distributed ledger system, maintained by a network of peers that monitors and regulates which entries are allocated to what Bitcoin addresses. This is done entirely by transmitting messages that are text, between the computers in the network (known as “nodes”), where cryptographic procedures are executed on these messages in text to verify their authenticity and the identity of the sender and recipient of the message and their position in the public ledger.

The messages sent between nodes in the Bitcoin network are human readable, and printable. There is no point in any Bitcoin transaction that Bitcoin ceases to be text.

It is all text, all the time.

The purpose of Bitcoin is to absolutely verify the ability of the owner a cryptographic key(which is a block of text) that can unlock a ledger entry in the global Bitcoin network.” — Beautyon

There are deep implications to understanding Bitcoin in such a way as it has ramifications to the fundamental freedoms 2(b) of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

Is IIROC, the national self-regulatory organization overseeing all investment dealers and trading activity on debt and equity marketplaces in Canada, and the CSA, aiming to challenge the Constitutional act of 1982 by trying to legislate software developments, text and messaging systems?

1.3 The General Understanding of Bitcoin is “Digital Gold”

The perception of value varies from one individual to the next. Individuals will purchase comic books, preserve them in their original sleeves without ever reading them. Others will purchase figurines, keep them in their original boxes and never play with them. Others will collect vintage cars knowing very well they can only drive one at a time. Other examples include watches, antique furniture, precious stones, paintings, sculptures, fine jewelry and wine.

The point here is their value is not tied to their use, but rather attached to the perceived value in the eyes of the owner. Gold has a valuation significantly above its industrial or ornamental usage. In today’s world, it is unlikely anyone buys a pair of shoes with gold. As such, bitcoin doesn’t need to be money (in the transactional definition of the term), but it can be valuable. What these examples have in common is scarcity. Some individuals will own them to store value, to brag, to seduce a mating partner or to speculate on the future price appreciation. Generally speaking, individuals will self-custody them.

I do not have the pretension to define something as complex and broad as bitcoin nor to define its full potential, for one reason: it is the free market that dictates what Bitcoin is. I invite the curious reader to consider these selected texts to realize the depth and uniqueness of the topic. For the first time in the history of mankind, a scarce digital asset exists. Bitcoin is not debt or equity; Bitcoin’s infrastructure permits the first digitally native bearer instrument without a central authority. Bitcoin is its own.

The monetary policy of the Bitcoin protocol is crystal clear. Its predictability, its limited supply and its stability at the base layer are valuable attributes. Accordingly, bitcoin is often referred to as “digital gold” (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7). Therefore, bitcoin can be viewed as a limited-supply consumer good.

It can be argued that bitcoin is;

- rarer than gold since technological innovation cannot increase its actual supply or the speed of production.

- more portable than gold as it can be used over the Internet, ham radio, satellite or paper.

- useful in a way that gold can’t be, as bitcoin can be programmed.

The curious reader will probably enjoy _Shelling Out: The origins of Money _by Nick Szabo. A special consideration must be paid to the concept of unforgeable costliness in the context of the energy consumption as it anchors Bitcoin is the physical world. Proof-of-work (energy consumption), the difficulty adjustment and the monetary policy are important concepts to understand in order to draw parallels and grasp the comparison with digital gold and to unbundle bitcoin from other crypto-assets.

Some won’t see any value and won’t buy bitcoin. This is simply how a market operates (i.e. where conflicting views meet). It is by the same market mechanism that someone did not invest in Amazon +/- 20 years ago when it was trading in the low double digits. Some saw value beyond a simple online book store, some disagreed, some have been rewarded, some have not.

Bitcoin is neither a debt or an equity instrument and from the start never fit the definition of a security. It can rather be viewed as a consumer good or a commodity and its dealing, trading and marketplace activities sit outside IIROC and CSA’s legislative scope.

1.4 How are the U.S. SEC and the U.S. CFTC Treating Bitcoin?

The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) has stated that Bitcoin is not a security. Here is a video interview dated June 6th 2018, where the Chairman of the SEC, Jay Clayton is crystal clear:

“…Cryptocurrencies, these are replacements for sovereign currency, replace the Dollar, the Yen, the Euro with Bitcoin. That type of currency is not a security. Let me turn to what is a security (…)”

The U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) has also already stated that:

“Yes, virtual currencies, such as Bitcoin, have been determined to be commodities under the Commodity Exchange Act (CEA)”

Why is it that a year later, Canadian securities regulators are still not clearly expressing themselves on the matter? Vague language such as “may represent’’ is used abundantly in their communications.

Just like a collection of rare butterflies, Bitcoin falls outside the scope of the security regulatory regime. This is valid for, but not limited to, the butterfly catcher, the distributor, the servicer, the collector, the curator and the gatekeeper.

Elisabeth Préfontaine, MBA, CFA, CAIA

Elisabeth Préfontaine, MBA, CFA, CAIA

To support this work, you may donate BTC to : 15Zb5wRJ95i2o5Pw6xSpz2xrHt2oL9xLmj

Octonomics is an independent research and consulting firm dedicated to financial technologies. More specifically interested in the fast and evolving world of Bitcoin, its ecosystem and applications.

A weekly newsletter is available by registering here.

A World Without Bitcoin

By Alex Gladstein

Posted February 11, 2020

The year is 2040, and cash is gone. The money you use on a daily basis has fully transitioned into a tool of surveillance and control.

In midtown Manhattan, you tip sidewalk performers with a scan of your wearable, your face, or your fingerprint. Coins and dollar bills are now curiosities—fossils from a forgotten age.

In Beijing, the government-issued Yuan has long since been digitized into the ubiquitous DCEP. Holding old paper notes is illegal, all payments are touchless or biometric, and all transactions are natively linked to your full identification stack. Every time you buy something, your national digital profile simultaneously updates.

Transaction privacy was one of the last freedoms to be stripped away in China. Now, your communications, movements, and interactions with other citizens are tracked with billions of cameras, real-time surveillance streaming from your wearables, swarms of micro-drone recorders, and immensely powerful algorithms, linking everything together in a panopticon.

In Caracas, Venezuela, the recovering economy runs on digital dollars. There is some street bartering, of course, but greenbacks finally became obsolete a few years ago, and other bearer assets like gold remain incredibly rare. If you want to buy something, you have to do it electronically and the transaction will be tracked and linked to your citizen profile.

In Lagos, like in many African capitals, all commerce is carried out on the rails of Chinese fintech, and everyone communicates seamlessly with the latest version of WeChat. The Nigerian economy runs on DCEP and the government and its 300 million citizens basically act as a Chinese satellite state.

At some point in the 2030s, governments around the world made cash illegal. They initially accomplished this feat through a demonetization process where public officials announced a new digital economy that they claimed would not leave anyone behind, would increase stability, and would make it easy to catch criminals and money launderers. Most citizens believed them.

Even in countries where the majority never had a brick-and-mortar bank account, all citizens were encouraged, then forced, to create ID-linked digital currency accounts accessible through their wearables or biometrics. Then, they were given a multi-year time window during which they could redeem their cash for a shrinking amount of digital credits. Almost everyone cashed in and went fully digital early on, when they could get the most credits. After the window expired, it became a punishable offense to carry paper or metal money.

Now, in 2040, there are two dominant currencies in the world: the digital dollar and China’s DCEP. The world is roughly divided: North America, Europe, and some top U.S. allies use the digital dollar, while the rest of the world uses DCEP. Very few other currencies remain.

Some rogue states still produce their own currencies, but these don’t last long and aren’t worth much to anyone else. These regimes tend to inflate their money supply extremely quickly, severely devaluing their currency, and eventually forcing authorities to create new currencies. This cycle destroys trust between state and citizen. Eventually, such governments give up sovereignty in exchange for survival and turn to the digital dollar or DCEP. The common person effectively has no ability to store savings in a way that isn’t controlled by either the American or Chinese government.

There hasn’t been any meaningful innovation in savings technology. Most citizens simply just save up their digital credits, but the value of their credits depreciates against real goods relatively quickly. And then there is autotaxing. By now, taxes are automatically deducted from your credit balance and tax rates rise unpredictably and always, it seems, too fast.

As in previous decades, some poor and middle class citizens still buy things like cattle or sheet metal in an effort to save against inflation, but all (save the 1%) are locked out of premium assets like real estate, fine art, vintage wine, and other scarce items.

Financial privacy has virtually disappeared, and not just in China and the DCEP countries. Along with the rise of ubiquitous surveillance cameras in public places – all linked together with AI-powered insta-analysis – all transactions are immediately linked to individuals. With cash gone, it’s extremely difficult to buy a burner phone or SIM card. Fines for trying to manipulate your credit wallets are harsh, and no one ever invented an alternative digital currency that was able to hold value.

Big data analysis wasn’t always so powerful. But it is now. Of course, humans had credit cards for decades, but unlike those early days, now governments can sift through all financial data with the press of a button.

To get credits, you need to provide ID. To use credits, you need to be loyal. To get the best perks, you need to be a perfect patriot. Around the world, digital currencies give governments unprecedented abilities to control their citizens. If your digital profile doesn’t have a top rating, you’re locked out of many public services and benefits. In dictatorships, if you dare to criticize the government, you immediately lose your financial abilities. Some say being in financial jail is worse than being in actual prison.

Corporations do create their own money. Libra was just the beginning. But all these credits are inevitably pegged to the digital dollar or DCEP, and therefore are surveillable, censorable, and confiscatable. They don’t offer an escape.

There has also been a dramatic increase in the real-time sale of your data and behavior to third parties. There is practically no way to buy something without your government and a range of corporations knowing. Instantly upon purchase, you’re met with a variety of advertisements. Many people have upgraded to smart visors and retinal implants, and they get advertisements there, too. Unless, of course, they can pay for the premium versions. In the DCEP countries, one can opt out of everything except government propaganda.

The public feared the rise of the Orwellian police state, and it came, but they also got the dystopia of Aldous Huxley. In this brave new world, a sophisticated constellation of carrots and sticks built into the financial system encourages and reinforces state-compliant behavior with impressive efficiency. Patriotism is addictive.

The Chinese social credit system, much mocked in the early 2020s, was finally implemented by governments worldwide in the ensuing decade, and with the transition into a fully digital economy, has become incredibly effective at stamping out dissent.

Governments ran sweeping campaigns to locate every single citizen within their borders and connect them to national identity systems. India’s Aadhaar was the first of many, initially promoted as a miracle for the unbanked, vulnerable, and stateless. But later, it became clear that these ID networks were just surveillance and exploitation machines.

Things are more fair for some, but a tiny few control everyone else in a way not even previously imaginable. The benevolent idea of “compliance” has led ultimately to slavery. It is the digital banality of evil.

Even now, governments continue to innovate their surveillance tech. Some citizens are being offered valuable perks for agreeing to install their credit wallets into their wrists or retinas. They say it’s the ultimate in touchless convenience. The program is popular. Some analysts say that by 2050, everyone will have one.

This could be our world.

But thankfully, this is a fantasy. In our world, we have an escape.

In 2009, a pseudonymous programmer by the name of Satoshi Nakamoto launched Bitcoin, a sovereign financial system.

Over the next few years, this decentralized money project grew. A global community made it strong, and grew a brilliant initial design into an unstoppable force. Over time, there were more nodes, more miners, more users, and more adoption.

By 2020, the separation of money from state had begun.

What was first a curiosity turned into a powerful global phenomenon. Once people understood they could digitally transact in a parallel economy that authorities didn’t control, they wanted to learn more and get involved. Satoshi pioneered a way out of the panopticon with proof-of-work, creating a non-governmental financial system.

Our future 2040 is still a horribly imperfect place, but omniscient tracking and surveillance is much more difficult for governments to achieve, because Bitcoin has enabled the survival of a digital form of cash.

So let’s rewind — let’s describe the year 2040 again, but what it could look like not just with government issued digital currencies but also with Bitcoin.

In the Bitcoin future, privacy has actually improved in some areas. With technological improvements in the Bitcoin software, it actually becomes very difficult for governments or corporations to track the Bitcoin use of citizens who practice good operational security. Bitcoin was at one point hard to access and clunky to use – just like email in the early 1990s – but things got a lot easier in the 2020s.

Governments promised waves of crime and terror if citizens dared to use a currency outside of state control. But those waves never came. By 2040, crime rates are essentially the same as they were for the previous century. In the Bitcoin world, however, it’s much more difficult for bankers to steal your money and for governments to devalue your savings.

Back in 2020, very few used Bitcoin, and even fewer understood its potential. A long hard road of education was to come. But later in the 2020s, universities began offering courses and degrees in Bitcoin. Eventually, one was able to get a bachelor’s degree or even a PhD in Bitcoin Engineering at any top university.

By 2020, tax authorities began asking citizens how much Bitcoin they held or sold, further increasing awareness among the citizenry. But by 2030, most people were using Bitcoin without knowing much about how it works, just as hundreds of millions of young people once adopted email without knowing how it worked.

Governments tried to prevent their citizens from using Bitcoin, but most measures and bans failed or were unenforceable. The permissionless nature of Bitcoin turned it into a virus that infected the surveillance state, preventing it from reaching its maximum potential.

Even in the most restrictive tyrannies, citizens figured out how to send Bitcoin back and forth in a way that was virtually impossible to effectively surveil at mass scale. Yes, governments are still able to police nations and communities, and investigators find most big criminals, but broad-based financial surveillance has been stopped in its tracks.

By this point, the Bitcoin network is protected by geopolitics. Part of Satoshi’s genius was creating an asset that would increase in value due to scarcity. Even bad governments which subsist on authoritarianism got involved in Bitcoin initially because of their greed. But over time, their reliance on Bitcoin shifted their local economy towards it, which in turn hurt their ability to control the money supply and financial system and ended up eroding their control over the citizenry.

The more democratic governments adjusted to life with Bitcoin. For example, many democracies changed the way they taxed their citizens, veering away from an income-based approach. Sales tax, VAT, and “citizen” taxes all became more important. Just as in the 20th century, taxation and the financial relationship between citizen and state continued to evolve in the 21st.

In democracies, the people created laws to allow daily small purchases to be completely private. You can buy groceries, have a small medical procedure, or buy an e-book or podcast without disclosing your identity. Because of this, your digital footprint ended up being much smaller than it would have been had all these events been tracked. Governments still ensure that larger purchases like cars, weapons, and homes require that the seller ID their customer, but for most purchases, your transactions are not uploaded to a national database—just like how things were in the cash age.

Critically, Bitcoin has allowed dissent to survive in an increasingly digital era. Independent media organizations and NGOs are still able to receive funding from supporters, even in the most difficult environments. In mega-cities, one can pay for public transport with Bitcoin-based payments, preventing the authorities from knowing your every step.

Ubiquitous surveillance cameras and data collection from next-gen social media still make privacy in general very difficult to achieve, but at least payments are protected. And Bitcoin becomes a native payment rail for pseudonymous social media platforms, where citizens can still enjoy avatars online, and practice digital freedom. Without a decentralized currency, all of this would be impossible.

I’ve painted two visions here.

On the one hand, an Orwellian dystopia.

On the other, an overly-optimistic techno-utopia. Neither will happen.

How close we get to a more positive and open financial future is dictated by what we do now with the Bitcoin ecosystem in 2020 and moving forward.

In this essay I propose six priority areas for you to consider getting involved with. There are of course more aspects of Bitcoin, but the ones I list here will be most crucial for us to tackle in the coming years.

A first priority area is global education. Only a tiny fraction of people on this planet use Bitcoin, and even fewer properly understand its power. The latest estimates put the total number of Bitcoin users at no more than 45 million people — roughly .058% of the world’s population. I personally interact with many at the top of the wider cryptocurrency and blockchain industry, ranging from executives to journalists to investors. My best estimate is that, at most, 25% of them understand the underlying principles of how Bitcoin works and why digital scarcity is the key to its success. It’s a back of the envelope estimate, for sure, but let’s just say that even inside the industry, the number of people who understand the impact Bitcoin may have on the world is small. There aren’t enough non-technical explainers; not enough university-level courses; not enough (or virtually no) journalists at mainstream media outlets who understand; few if any initiatives to try and bring this topic to the attention of policymakers, philanthropists, and public figures; and no good Bitcoin film or video content on platforms like Netflix. There is much work to do.

A second priority area is usability. Just as the mobile phone and email were hard to use at first, and only popular with the scientific or economic elite, Bitcoin has begun its life as a niche technology. We should try to break this bubble. In order for that to happen, the average user needs to be able to send and receive Bitcoin with a few clicks and a swipe. But this will take time, as all users should be able to easily control their own keys without relying on a third party. Bitcoin usage needs to be simplified without making critical tradeoffs with regard to decentralization, privacy, or sovereignty. Technical complexity needs to be minimized as well, as Bitcoin should be accessible to those who need it most around the world, who have the least powerful devices and least consistent internet access. Thankfully, things are moving in the right direction. Even in just the past two years, Bitcoin wallets have become much, much easier to use. Just as sending email transformed from a complex task to a swipe on an iPad, Bitcoin will eventually simplify. Already, unnecessary details are being gradually hidden from the end user in the same way that Signal, for example, made private communications much easier and more widespread than previously possible with clunkier tools like PGP.

Which brings us to the third priority area: privacy. It is critical that privacy be encouraged, normalized, and baked into the Bitcoin ecosystem. Critically, we want Bitcoin on-ramps, wallets, and payment networks that are open source, decentralized, and relatively private. For example, BTCPay Server is perhaps one of the most important technologies in Bitcoin today. Originally a clone of Bitpay, today it allows anyone to set up their own hosted payment server, allowing them to receive donations or payments in Bitcoin, in a way that is much more privacy-protecting. Each transaction is done via a unique invoice, and can be dumped into a wallet that isn’t attached to your ID. This will prove equally important for mom-and-pop corner stores as it will for non-profit organizations operating under authoritarian regimes. Other key innovations in this space include the upcoming Taproot upgrade, which will help reduce the amount of information Bitcoin transactions leak on the blockchain; innovations in mixing technology like CoinJoin that help camouflage users; and, of course, the Lightning Network, which takes transactions off the surveillable chain into a second layer.

This brings us to our fourth priority area: scaling. All base monies need to be scaled through secondary layers to have a global impact. Consider the gold-based economy, where we invented paper notes to help scale commerce. Or the dollar-based economy, where companies like Visa helped spark growth around the world. For Bitcoin, the most promising scaling solution is the Lightning Network: an open source, decentralized payment system. You can think of Lightning as digital cash to Bitcoin’s digital gold. At the moment, the Bitcoin network can only support around 7 transactions per second. With Lightning, there is no technical upper barrier to how many transactions per second we can do with Bitcoin. This technology is still nascent, but arguably essential for Bitcoin to become usable by hundreds of millions of people in a non-custodial way. If we want to scale Bitcoin to the masses, without them having to trust a third party, Lightning seems to be the way forward. Companies as big as Square seem to agree: there, CEO Jack Dorsey has created Square Crypto, a research group that is building a Lightning toolkit for developers. This kind of scientific exploration is important for other companies and universities to emulate and expand on in the coming years.

A fifth priority area is liquidity. Once the average person can acquire Bitcoin, the following step, at least for the next few decades, is to ensure that it is easy for them to convert their BTC to local fiat currency when necessary. A world in which we pay for everything or even most things with a Bitcoin-based system is far away, and may never come at all. For now, people in distressed or repressed places need an ability to shave off their Bitcoin into fiat to pay for daily expenses and bills. This, thankfully, is getting a lot easier. In most major urban areas on earth, there is some mixture of Bitcoin ATMs, peer-to-peer marketplaces, Bitcoin brokers, and brick-and-mortar exchange points. Expanding Bitcoin off ramps will be key to popularizing the technology in the future. The website UsefulTulips.org does a good job of analyzing Bitcoin’s growing use around the world. More initiatives like this are necessary so we can learn how and why people are using Bitcoin.

A sixth priority area, and one that might really move the needle, is minimum ID. There is a strong need for a platform like Twitter that still allows some level of pseudonymity to adopt a Bitcoin-based payment system that reveals an absolute minimum about the user. If avatars online are to exist in the future, we must be able to operate them securely without fear of our real life identities being leaked. So attaching a bank account or a credit card with our full ID stack on it to our social media account won’t do us any good. We’ll need to use digital assets that don’t require Know Your Customer (KYC) or Anti Money Laundering (AML) compliance. Lightning seems well placed to serve this function. The less we reveal about ourselves in our transactions, the harder it is for Big Brother or surveillance capitalism to grow. There could very well be a future, even a near future, in which an individual can walk into a coffee shop, buy something online, send money to a friend, and make a donation to a cause all while giving up just a minimum amount of information about themselves.

If developers and investors can focus on these six areas; if consumer protection advocates can lobby for the space for them to grow in our societies; and if users can more easily engage with Bitcoin, then we are well on our way to a more private and free world.

In conclusion, let’s revisit the impact Bitcoin could have on human rights communities if its technology ecosystem grows along the lines we’ve described.

First, consider independent journalists and NGOs operating in authoritarian environments who need to preserve financial independence. With Bitcoin, they are able to collect funds from around the world in a way that is difficult to surveil and impossible to stop. Then they can convert it into local fiat currency on an as-needed basis to pay for program expenses. This is already relevant in places like Russia and Hong Kong where the bank accounts of activists are frozen.

Second, consider the billions of refugees and stateless individuals, who cannot currently access the banking system. Today, you need to prove your identity to open a bank account or use any of the apps attached to the legacy financial system. With Bitcoin, you don’t need an ID or a passport. You just need, practically speaking, a smartphone and access to the internet. This is a great equalizer, giving anyone, no matter their class, education, background, or ethnicity, equality of opportunity.

Third, consider individuals who are dealing with high or hyperinflation. Many countries have been hit lately with double digit inflation, and some have suffered through hyperinflation. Ask any Argentine, Syrian, Turk, Iranian, Zimbabwean, or Venezuelan and they will tell you how rampant inflation can crush economies and vaporize the savings of the lower and middle class. With Bitcoin, anyone has access to a savings technology that requires no permission from a company, and cannot be devalued by a government that decides to print more money.

Fourth, consider the growing number of people who are falling under intense daily financial surveillance. Especially in China, hundreds of millions of citizens are increasingly being watched not just by hundreds of millions of surveillance cameras but also through their texts, calls, and social behavior. Transactions are a big part of this trend and will continue to be increasingly surveilled. Bitcoin provides the infrastructure for a parallel economy, one in which our financial transactions are not natively linked to our identities.

Fifth and finally, consider those who are victims of sanctions. The tragic fact is, individuals who live in sanctioned countries like North Korea and Iran didn’t vote for their governments in free and fair elections and shouldn’t reasonably be held responsible for their dictator’s crimes. Through Bitcoin today, individuals inside Iran, for example, can earn income from abroad by working on open source software projects, or can receive money from their family abroad to pay for basic expenses or medical bills at home.

If the Bitcoin project falters or slows, then there won’t be much hope for the billions of people in these situations around the world, especially as cash fades. Private payments will be practically impossible. All daily transactions will become increasing points of surveillance and control. The monetary substrate itself will be watching you, and controlling you—and you won’t be able to do anything about it.

One more thing to keep in mind: the Davos elite who currently run the world are threatened by a technology that separates money from state and provides permissionless access to a premium savings technology. They are used to running things and want the game to be rigged. They want there to be obstacles and barriers to entry. Bitcoin will frustrate them because anyone can access it and use it, no matter who they are. In the progression of the global banking elite first ignoring Bitcoin, then laughing at Bitcoin, then fighting Bitcoin, and then giving up, we are nearing the end of the laughing phase. A big battle is on the horizon.

The good news is, there is excellent momentum for Bitcoin in the areas we’ve covered, and there is growing global adoption. Despite the obstacles, the path to freedom is clear.

In an age of increasing fear over how corporate and state technology will steal our rights and freedoms, we can be grateful to Satoshi that we won’t ever have to live in a World Without Bitcoin.

Tweetstorm: The Pump

By Brendan Bernstein

Posted February 11, 2020

Most people think BTC is going to pump from a Zimbabwe esque hyperinflation.

But the opposite is going to happen

We’re on the precipice of a deflationary crisis….and this is why BTC will pump

Here’s why:

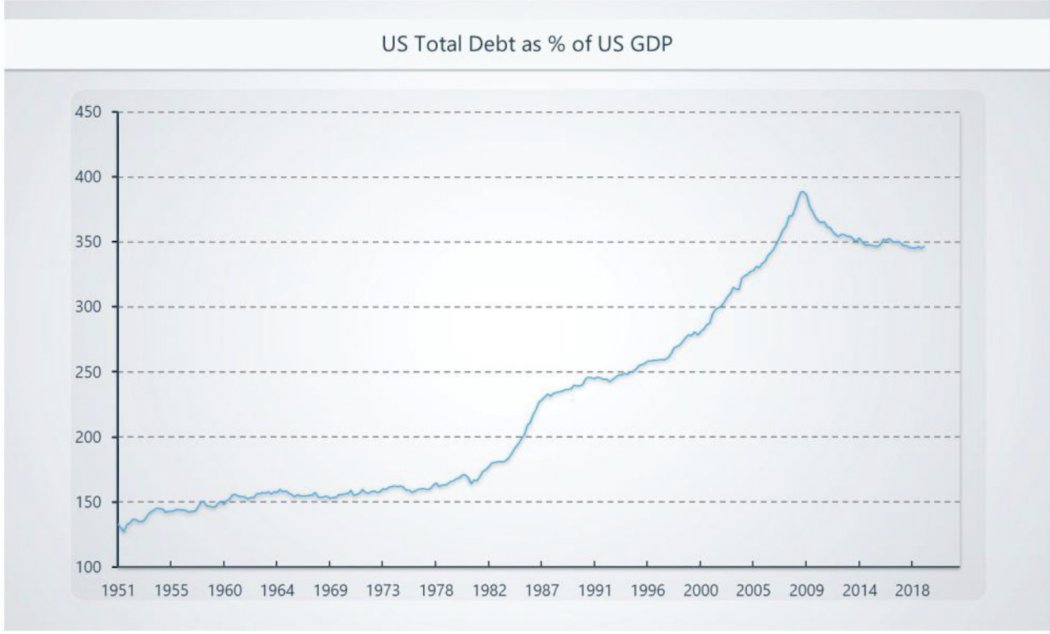

Debt has peaked and is beginning to turn.

As people deleverage, this suppresses inflation bc income goes to debt servicing instead of goods & services.

This is why the fed can pump $4tn into the economy and CPI doesn’t budge.

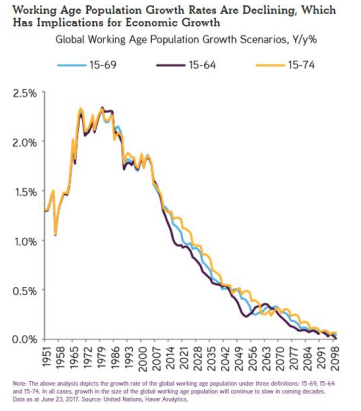

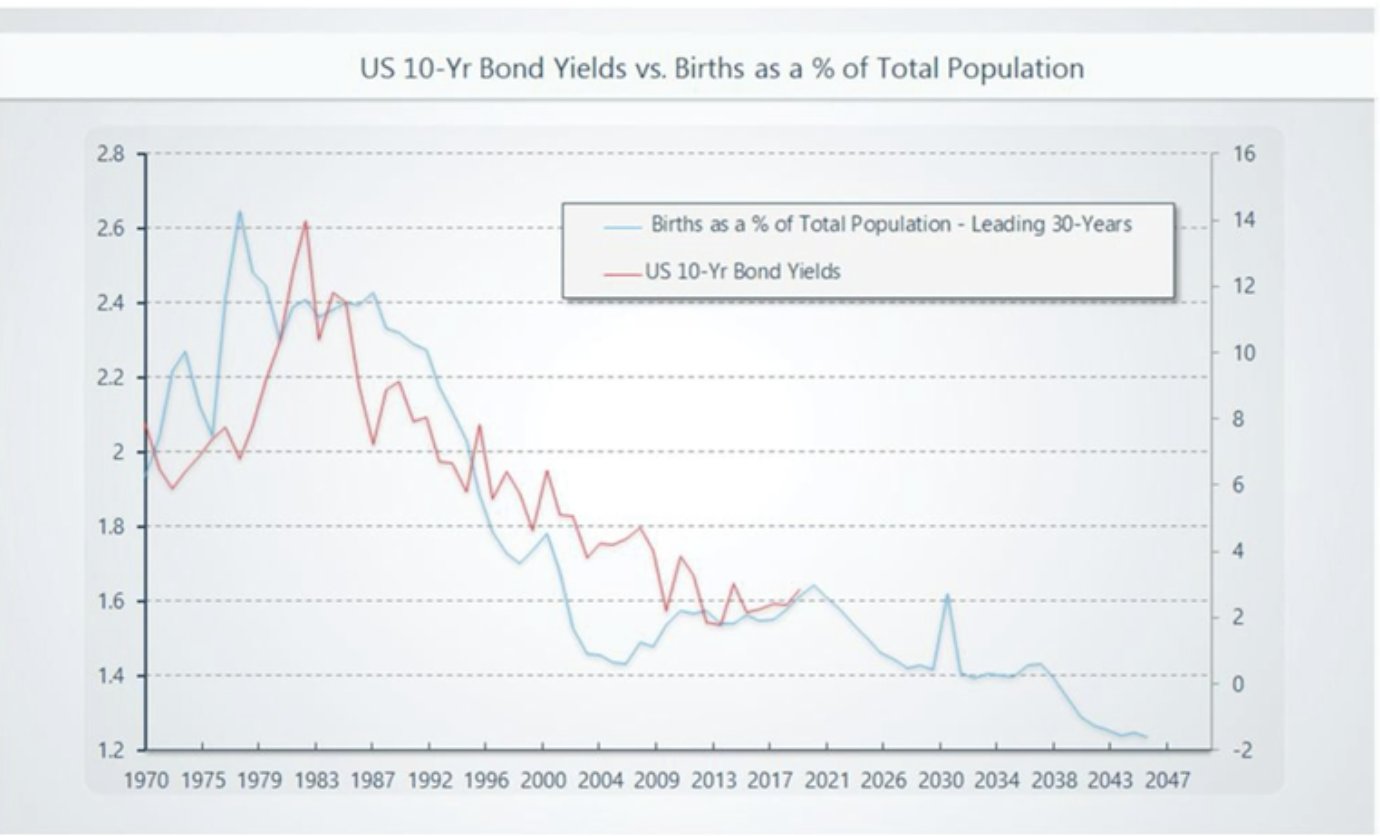

Growth is also a product of demographics. Boomers are the largest demographic and their retirement is peaking in the next 5 years

Over the last 100 years, labor force grew 5x. Over the next 100, it will only grow 20%.

There will be less and less money to spend.

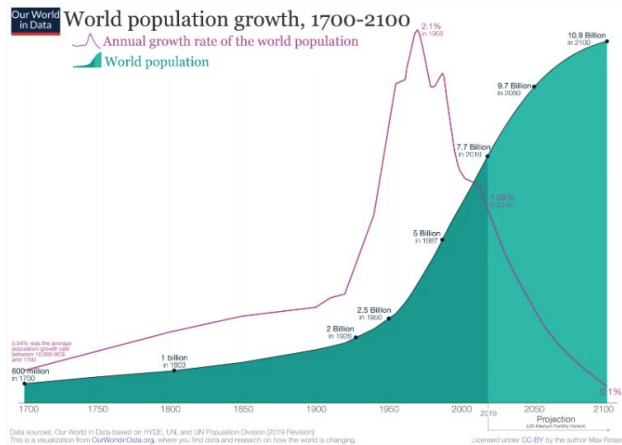

Additionally, GDP growth is directly tied to population growth.

Population growth peaked in the 1960s at 2.1% and will hit 0% in the next 100 years.

This massive tailwind is shifting to a headwind.

Population growth increases demand for goods, inflation and the stock market.

The success of our consumerist capitalist society may just be a product of labor and exponential population growth.

This is also why a $tn tax cut and $300m in fiscal spend led to almost no growth.

Boomers, which were a massive spending and stock market growth tailwind, are going to turn into a headwind this year.

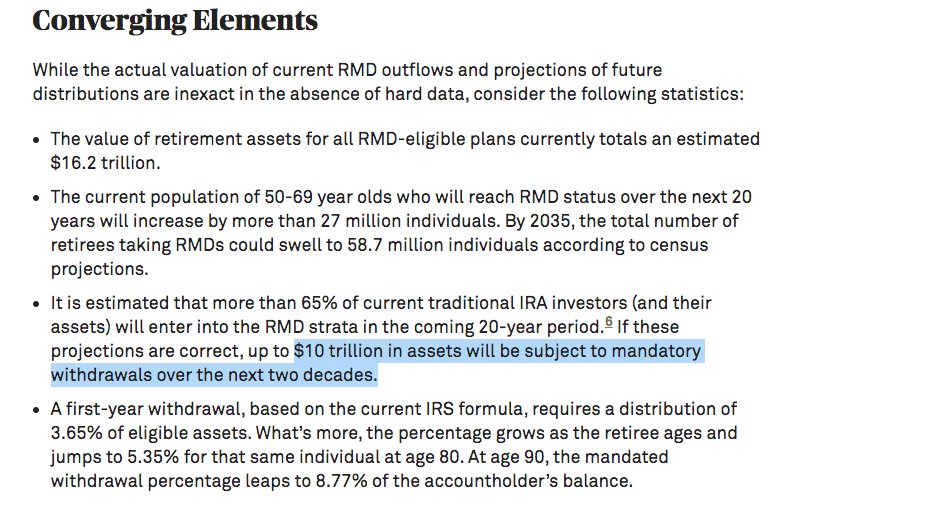

The RMD law requires that they take cash out of the stock market.

As a result, up to $10tn in assets will be subject to mandatory withdrawals

The problem is that we are at peak debt and the stability of our society rests on an increasing stock market and increasing growth to service that debt.

Stock market declines are a national security concern.

And the fed will be forced to plug this hole.

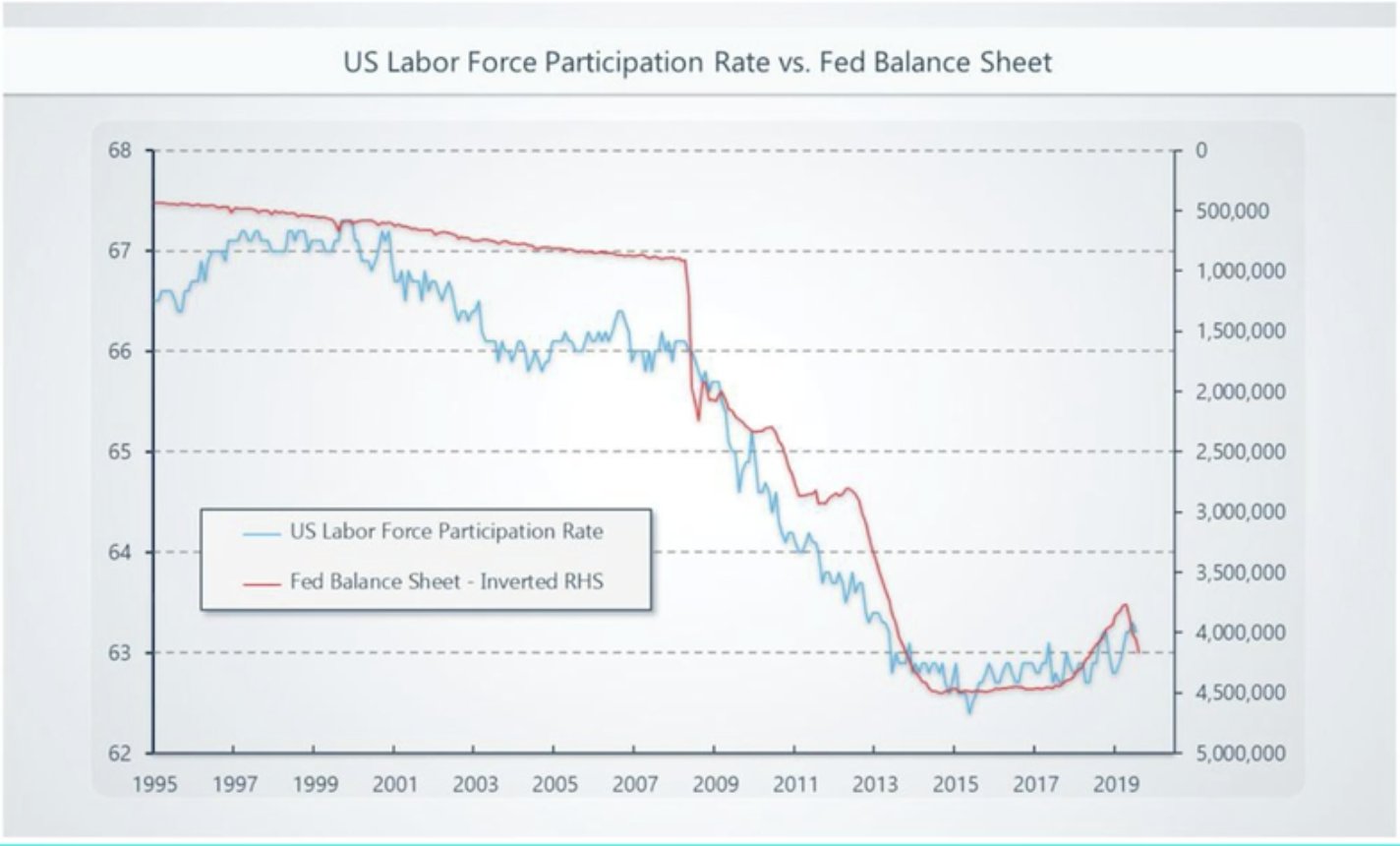

This great chart from @RaoulGMI shows the US labor force participation rate overlaid with the fed balance sheet.

As more people leave the work force, the fed has been plugging the gap by expanding their balance sheet.

This trend is only accelerating and based on the upcoming boomer retirements, this correlation would predict a doubling of the fed balance sheet over the near term.

Many people assume Bitcoin is going to stave off a Zimbabwe-esque hyperinflation of the USD.

But because of the demographic, population growth and debt dynamics, it’s much more likely the opposite occurs.

Extremely low growth and Japanification of the world

Long adult diapers

Negative rates will be the norm in this world.

But because our system is predicated on growth, the fed is going to be forced to go to extreme measures to counter it.

It’s not a question of if we get MMT, but when.

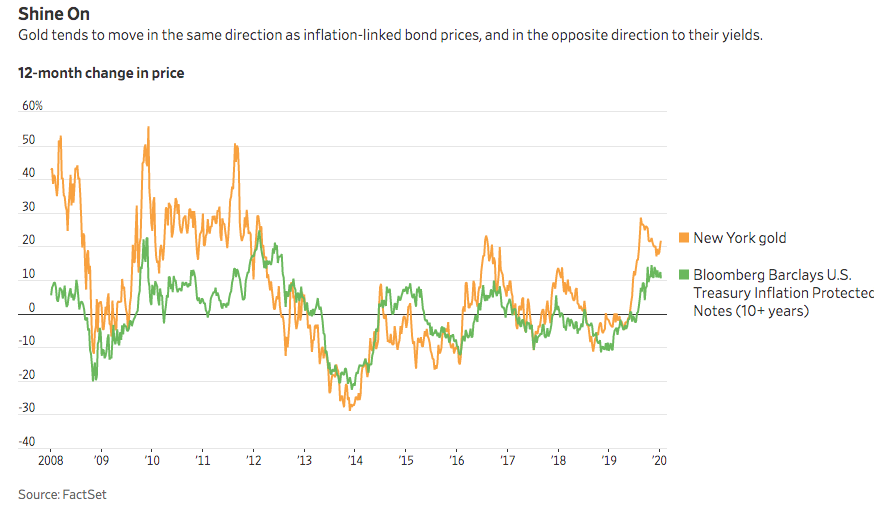

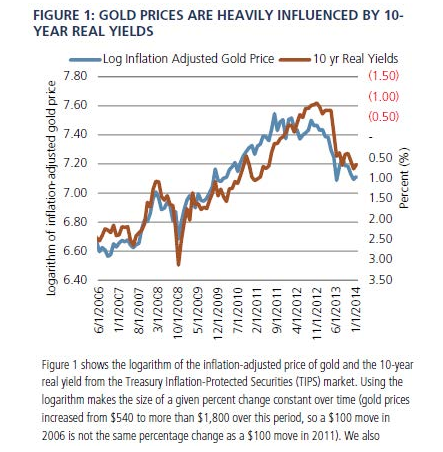

The best predictor of gold prices (and bitcoin prices too ultimately) is not the dollar or inflation…it’s real yields.

The fed’s hands are tied.

Over the next 50 years yields will be absolutely crushed.

And there could be nothing better for scarce assets like bitcoin and gold as the Fed is forced to ramp up printing to attempt to counteract these trends.

There’s a black hole in the pension system. Inequality is ramping up. Geopolitical instability is festering.

The fed is going to be forced to prop it up all up and anesthetize everything to death.

Sayonarah to any fiat purchasing power. Long scarce assets.

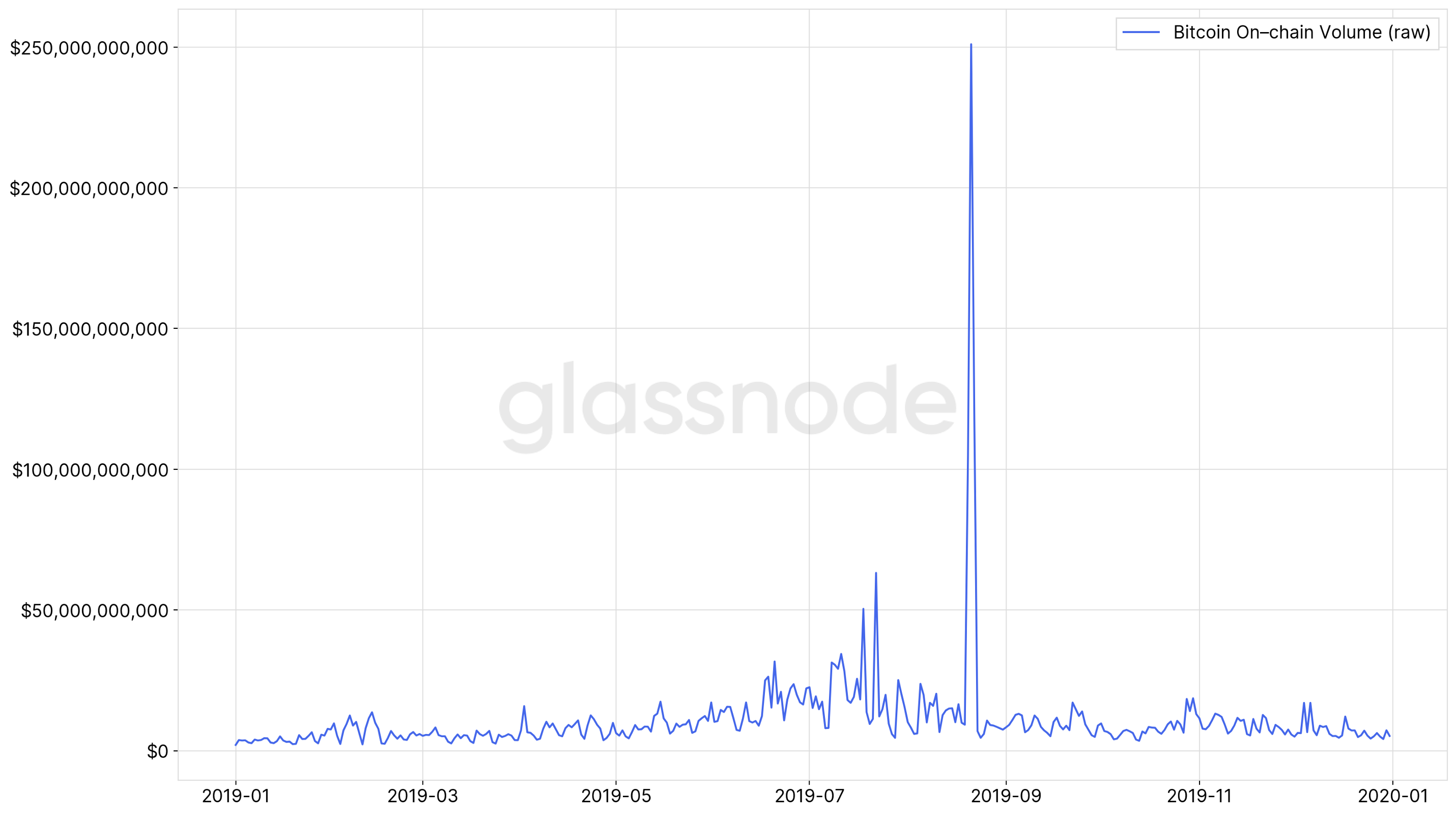

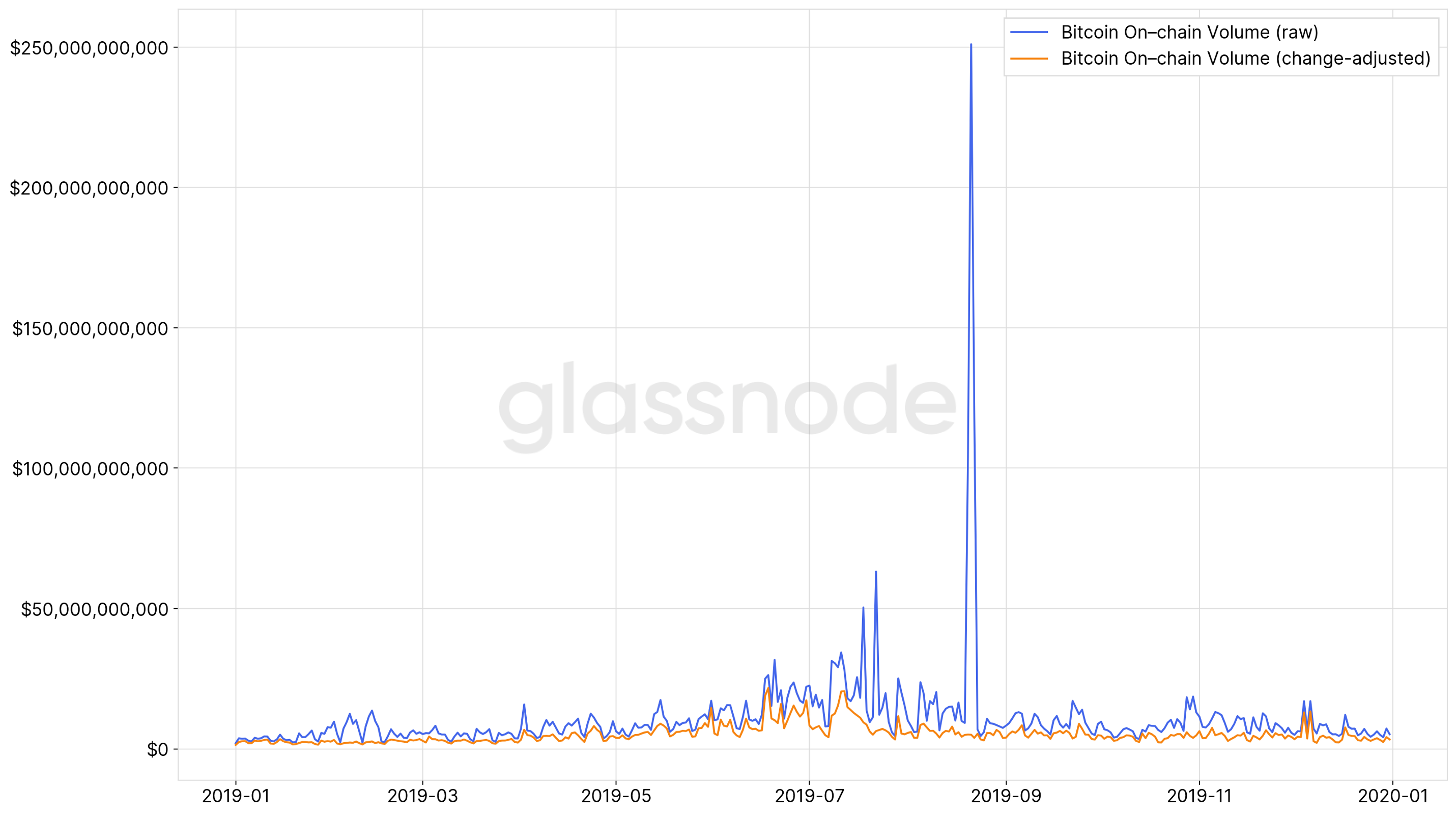

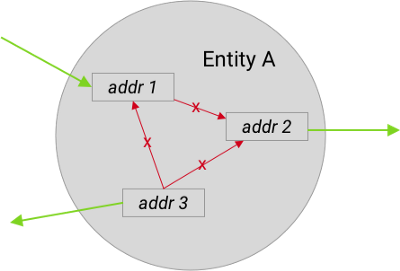

Over 75% of Bitcoin’s On–Chain Volume Doesn’t Change Hands

By Rafael Schultze-Kraft

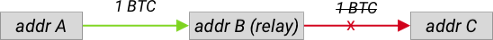

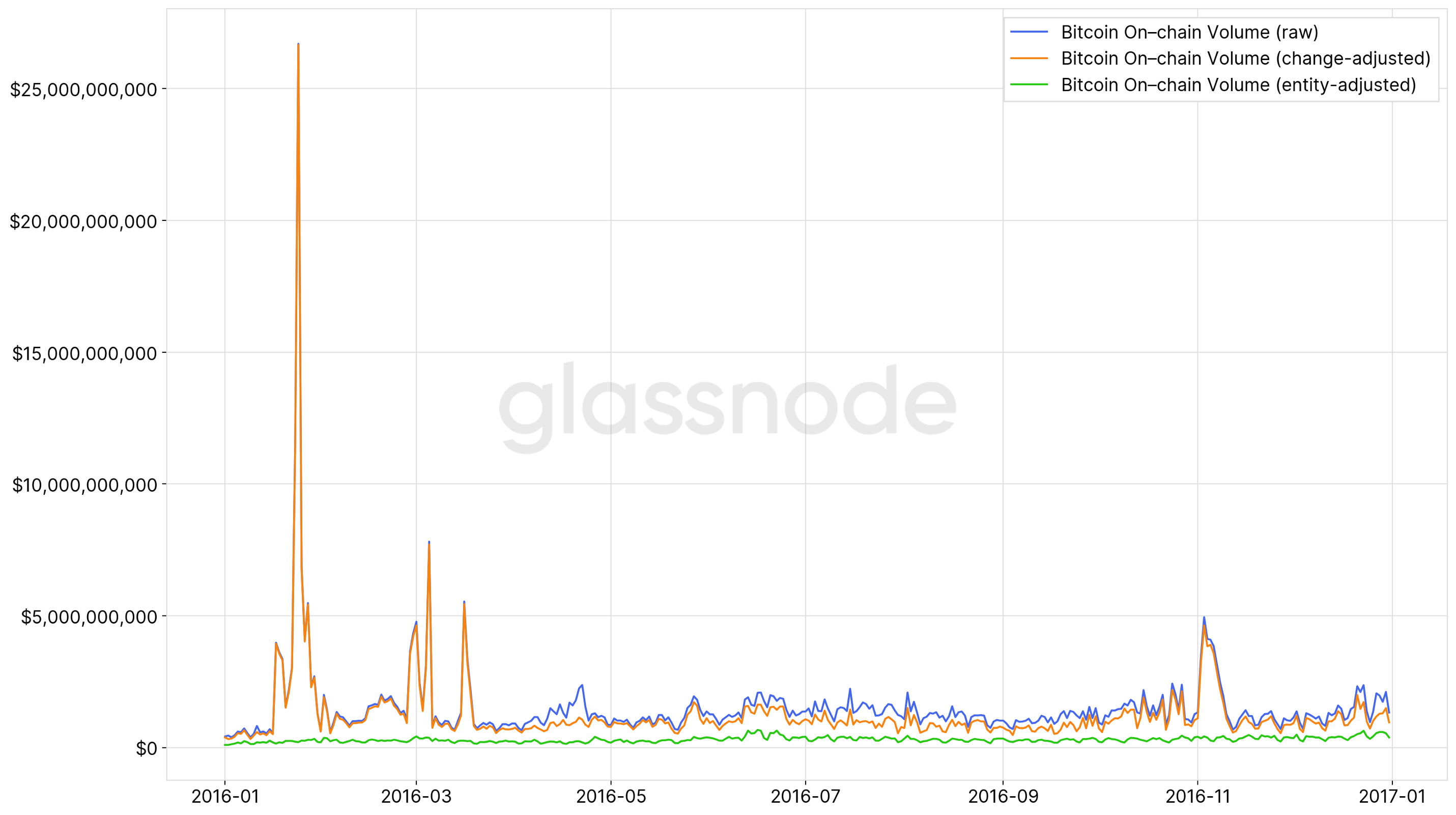

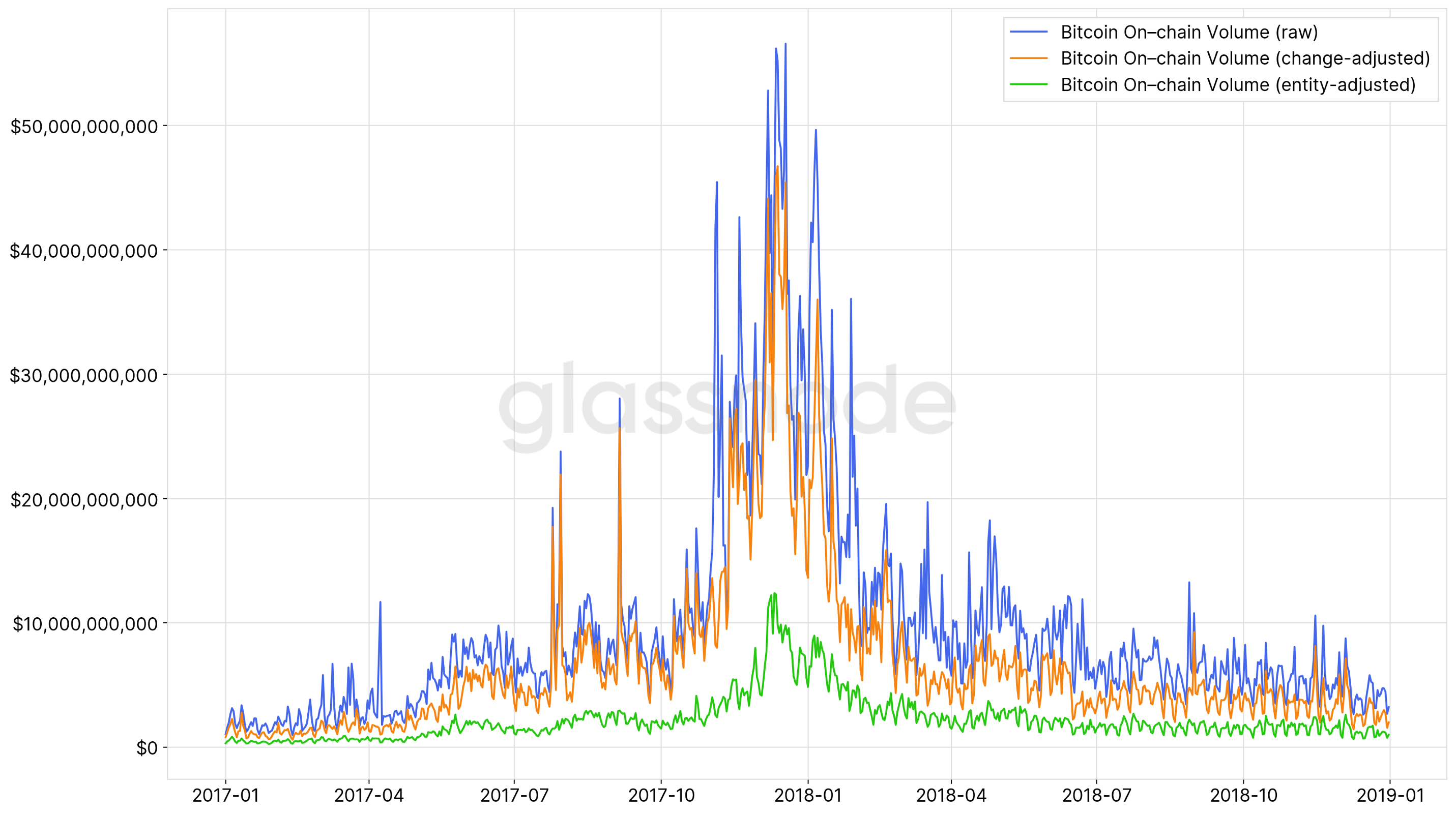

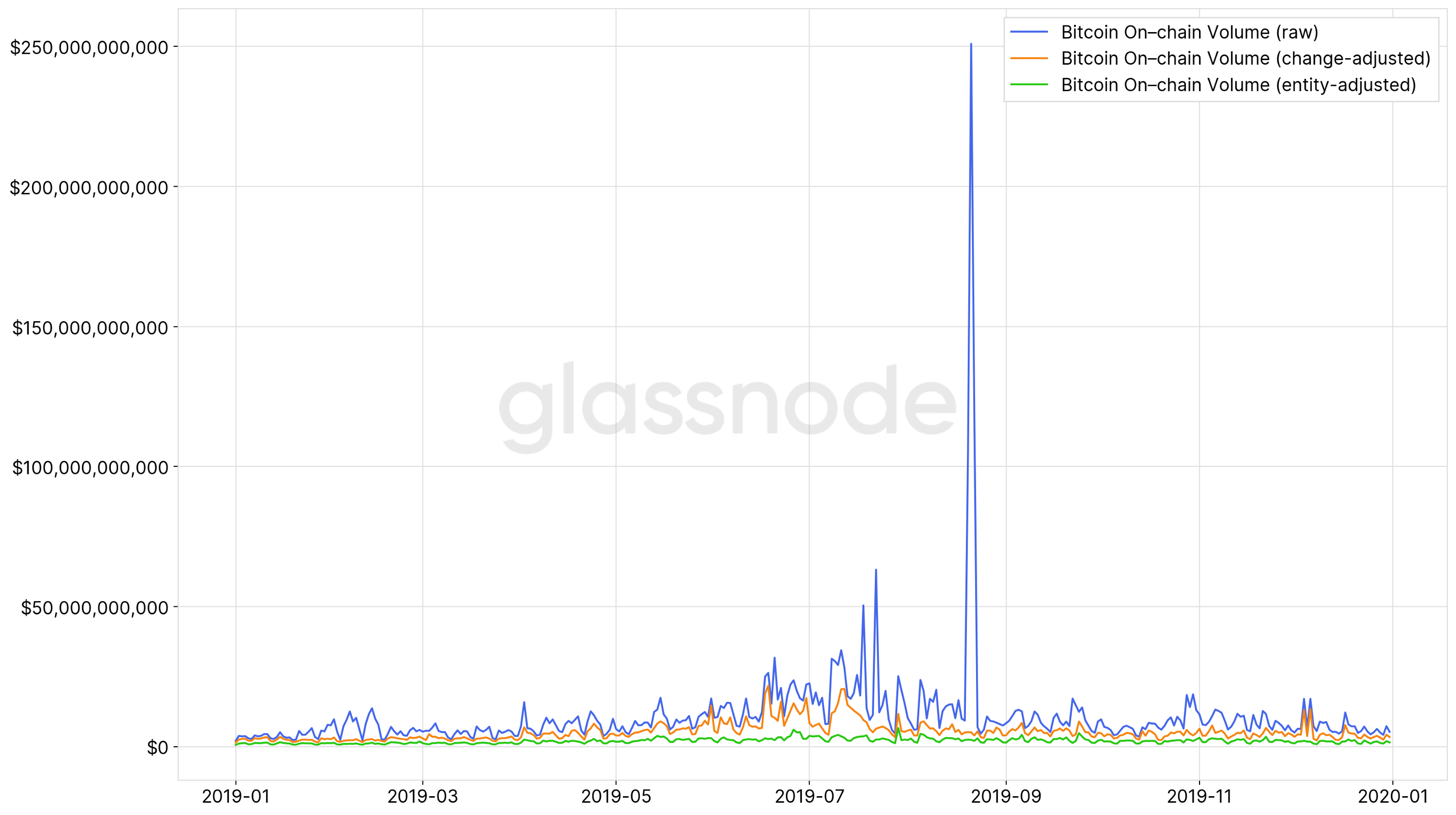

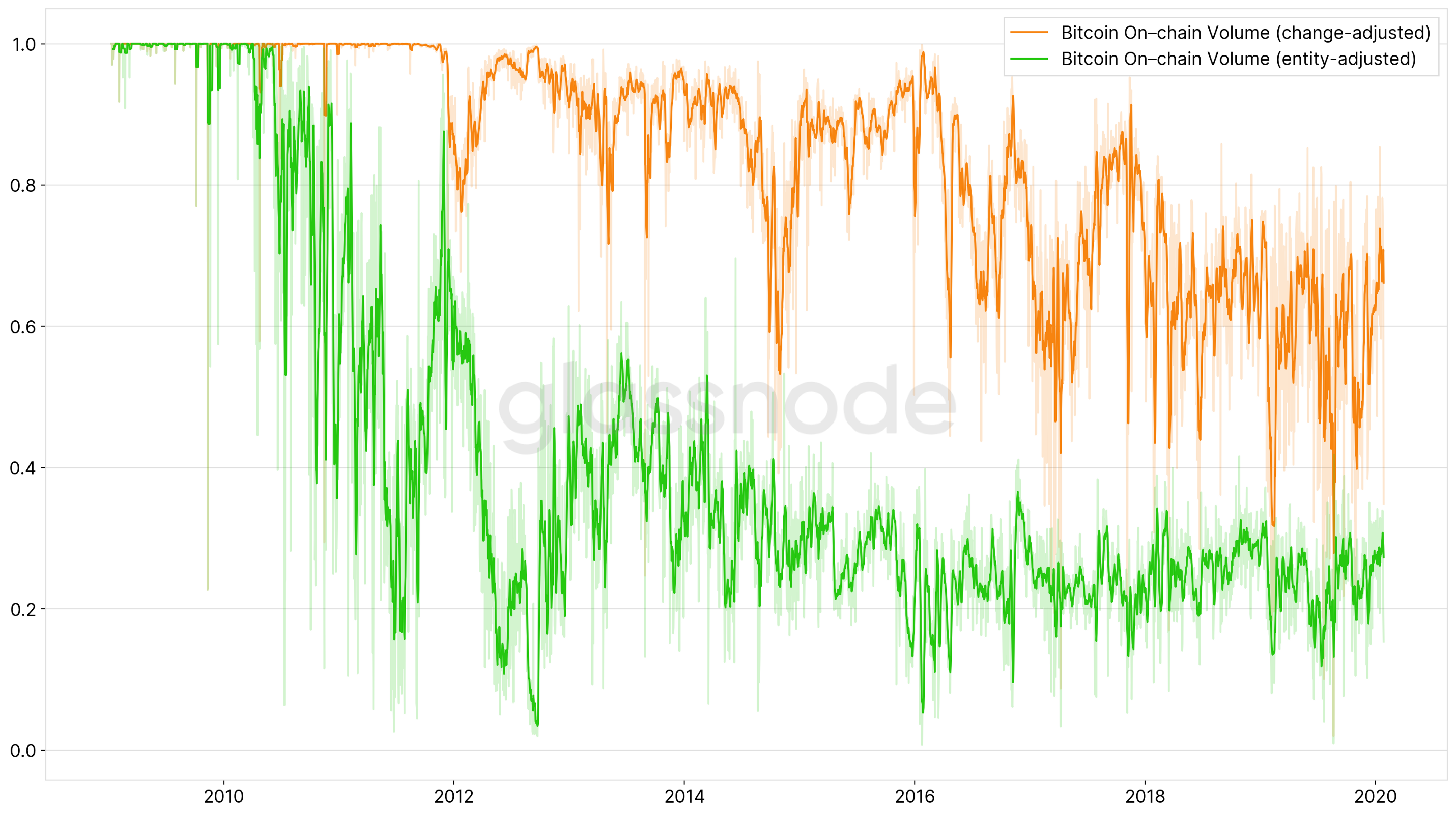

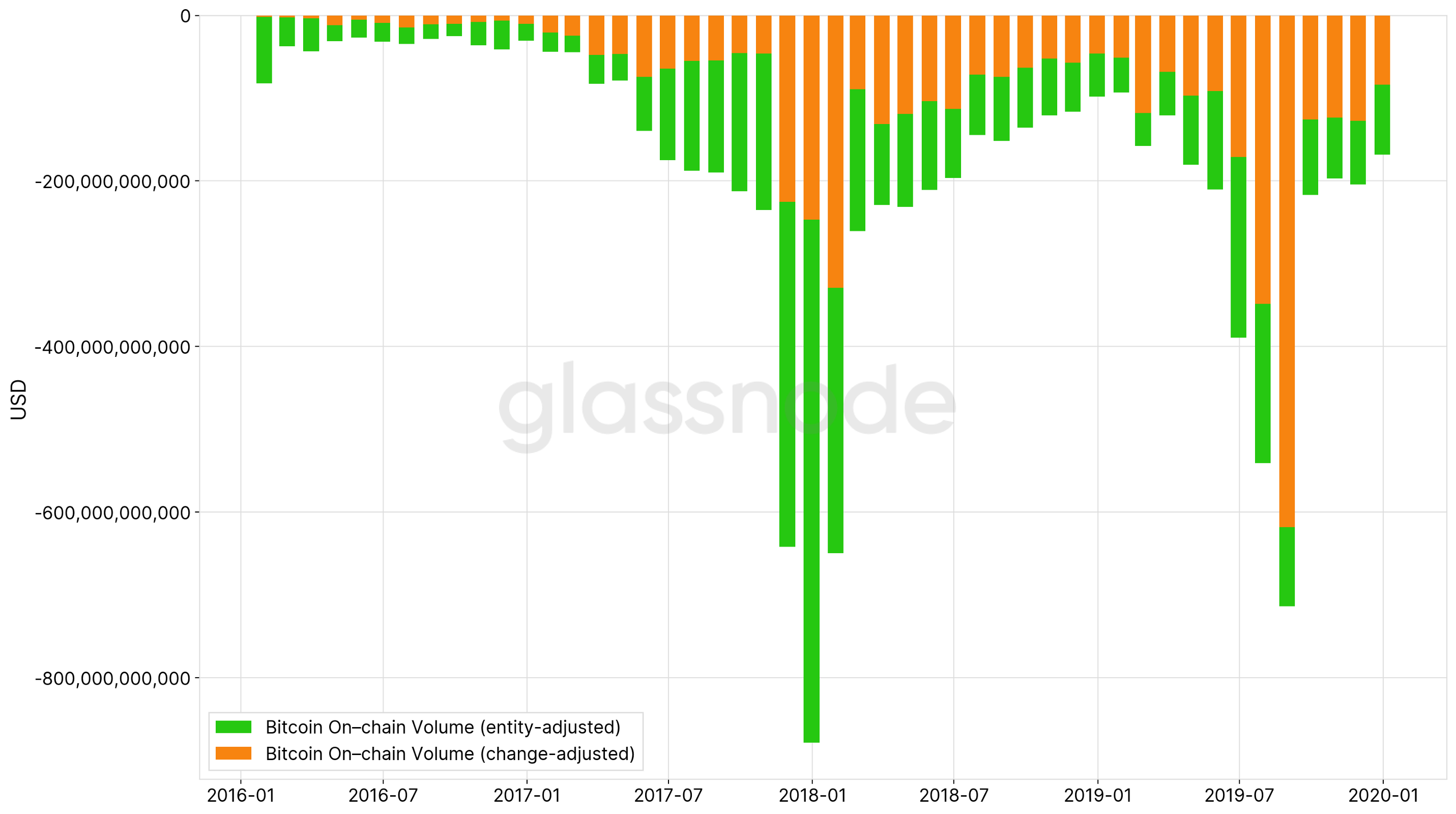

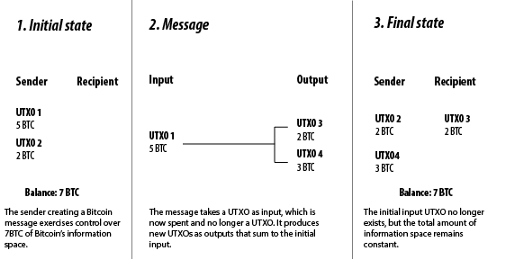

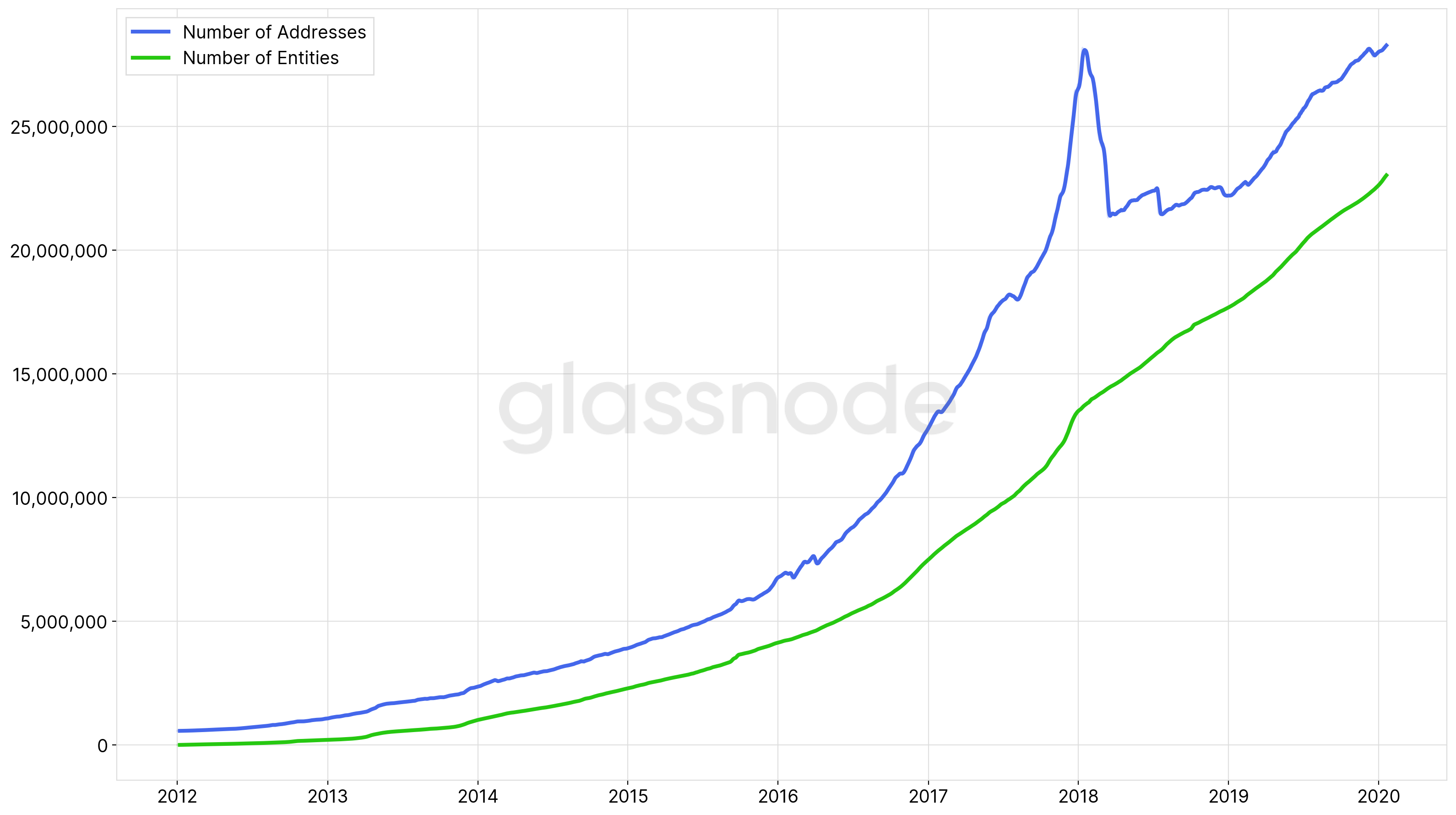

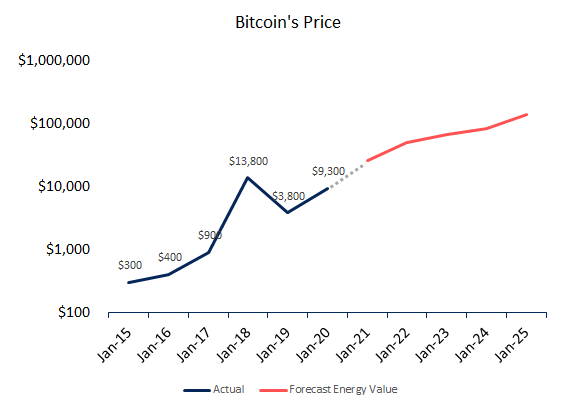

Posted February 13, 2020