WORDS is a monthly journal of Bitcoin commentary. For the uninitiated, getting up to speed on Bitcoin can seem daunting. Content is scattered across the internet, in some cases behind paywalls, and content has been lost forever. That’s why we made this journal, to preserve and further the understanding of Bitcoin.

WORDS is a monthly journal of Bitcoin commentary. For the uninitiated, getting up to speed on Bitcoin can seem daunting. Content is scattered across the internet, in some cases behind paywalls, and content has been lost forever. That’s why we made this journal, to preserve and further the understanding of Bitcoin.

Donate & Download the July 2018 Journal PDF

Remember, if you see something, say something. Send us your favorite Bitcoin commentary.

Crypto-incrementalism vs Crypto-anarchy

By Tony Sheng

Posted July 2, 2018

A close friend of mine invests in crypto. He focuses on projects that either help with regulatory compliance or fiat inflows (e.g. institutional custody). He sees value in blockchain and the surrounding ecosystem not as an unstoppable force that tears down borders, undermines governments, and shepherds in an era of crypto-anarchy, but as nothing more than a new data structure with potentially disruptive use-cases.

Let’s call this crypto-incrementalism.

My other friends want unstoppable, unseizable money that cripples legacy financial institutions; a transparent, uncensorable information infrastructure that precludes any abuses from states or corporations; true privacy and anonymity such that participants are completely unidentifiable by those that would seek to harm them; a society built on technologies unable to comply with authoritarian requests.

Let’s call this the crypto-anarchy1 .

Crypto-incrementalists and the crypto-anarchists share strong convictions in the power of decentralization. Both can get excited about Satoshi’s vision to improve on a financial system that relies “almost exclusively on financial institutions serving as trusted third parties to process electronic payments.”2

Nobody mourns the removal of the middle-man. It’s a powerful starting point for crypto-incrementalists and crypto-anarchists alike.

However, these groups diverge quickly as we move from the abstract to the material. How should we handle a government’s request to identify an individual using a cryptocurrency? How do we return assets stolen in a hack? How do we enforce legality for tokenized physical assets (e.g. real-estate)? Or tokenized securities?

Crypto-incrementalism

Crypto-incrementalists think it’s okay–even preferable–to design crypto systems able to comply with requests from governments and corporations. Assets stolen? Use a back-door to reverse the transactions. Need to enforce legality of tokenized securities? Design around the existing legal infrastructure so the legal system is the “source of truth.” Here, the benefit of crypto is to reduce inefficiencies in existing systems by applying a new technology. Working with governments and corporations is the easiest way to drive that adoption.

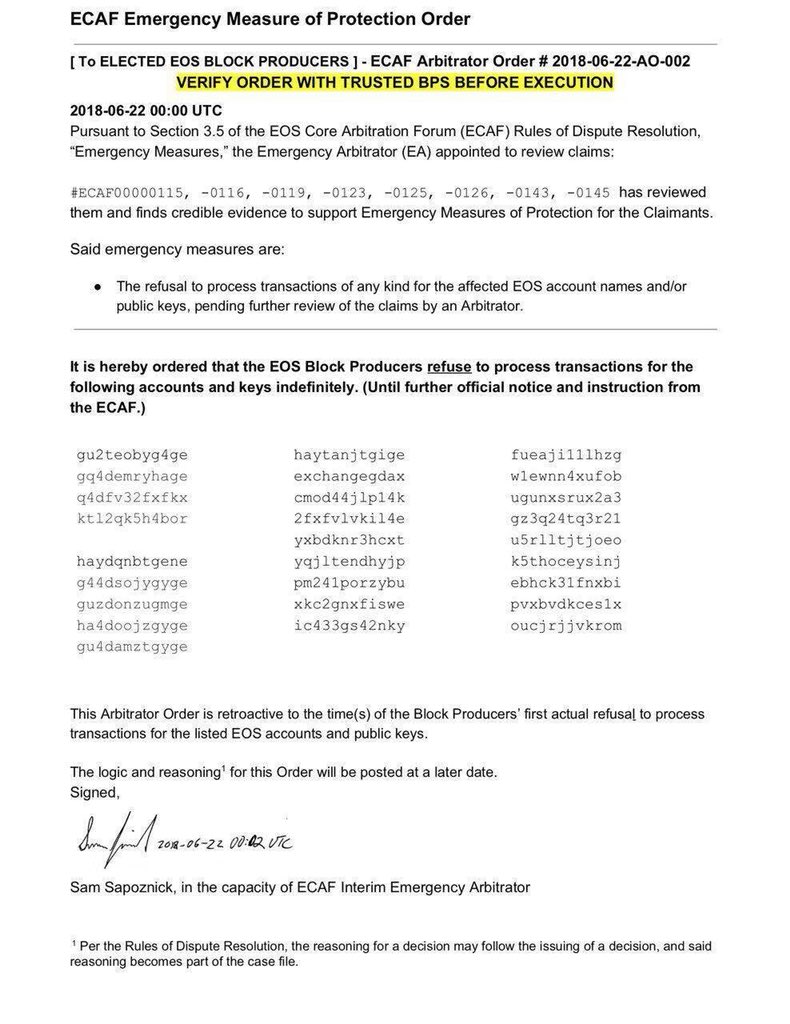

Recent actions by the powers that govern EOS provide an instructive example. On June 22nd, the “EOS Core Arbitration Forum (ECAF)” asked the 21 EOS block producers (the 21 entities that decide what “truth” is on the chain) to freeze seven accounts, providing no explanation. The ECAF stated, “the logic and reasoning for this Order will be posted at a later date.” Alarmingly, all 21 block producers complied.

Such a process gives EOS the flexibility to deal with malicious actors, but comes at the cost of potential abuses. It’s not hard to imagine a scenario where hackers sent a similar decree to the block producers. Or for ECAF to ask the block producers to freeze accounts on behalf of a government.

This is a trade-off. Acceptance of these risks offers a way to incorporate blockchain into some very large industries such as enterprise blockchains, security tokens, tokenization of physical assets, and more. For these use cases, a centralized entity has authoritarian control of the protocol by design–it’s the only way to comply with existing financial and legal systems. Debates around these use cases tend to reduce to this single design choice that is exciting to crypto-incrementalists and repulsive to crypto-anarchists.

Crypto-anarchy

Crypto-anarchists want information infrastructures that are, by design, unable to comply with authoritarian requests. Assets stolen? Nobody has the power to reverse the transactions: best we can do is fork the protocol. Need to enforce legality of tokenized securities? Hard af and probably not worth working on. Want to identify an individual participant in the network? Sorry, that data does not exist. Any designs that make a protocol vulnerable to authoritarian control render said protocol useless. For crypto-anarchists, the success is binary: sufficient protections against centralized powers, or insufficient. Anything “in the middle” is insufficient.

Why require complete decentralization and privacy? The corner cases are unacceptable. Members of a persecuted minority could get their funds frozen, speech censored, identity deleted by an evil government. Even if the government couldn’t directly freeze the funds (e.g. we’re all using a Bitcoin), without sufficient privacy, they could identify the addresses belonging to members of the persecuted minority and take actions on them physically or through the ecosystem surrounding Bitcoin (e.g. retailers).

Use of popular decentralized networks are not yet sufficiently private. Torrent users will often receive cease-and-desists from their internet providers. Bitcoin users have been routinely identified for innocuous and criminal purposes. Users aren’t sufficiently protected for two reasons: (1) privacy technology is not yet built into networks like Bitcoin, and (2) users are largely uneducated on privacy preservation, and unbeknowingly identify themselves with things like their IP address.

Is decentralization good enough? If Bitcoin cannot comply with an authoritarian request to seize funds (which it cannot), doesn’t that satisfy the needs of crypto-anarchists? It’s certainly good, and covers the majority of authoritarian requests, but does not protect users from e.g. physical violence. While a user can’t have their funds seized at the protocol level, if their identity is exposed, a powerful entity could find them physically and coerce them.

Luckily, lots of exciting work is happening around privacy. There are privacy-forward cryptocurrencies like Zcash and Monero, projects like Enigma and Keep, and the big protocols like Bitcoin and Ethereum have plans to improve their privacy technology.

Use cases

Here are some example implementations of the most commonly discussed use cases for crypto.

Money

- Incremental: a cryptocurrency that can, without the consent of the majority of the network, report the identities and behaviors of participants in the network to governments, freeze or seize balances, or change the “rules” (e.g. monetary policy)

- Anarchic: a cryptocurrency that is unable to comply with authoritarian requests (e.g. Bitcoin) and offers strong privacy guarantees (e.g. Zcash)

Computing platform

- Incremental: a smart contract protocol that can, without the consent of the majority of the network, blacklist accounts (e.g. EOS) or prevent access to certain groups (e.g. private blockchains).

- Anarchic: a smart contract protocol that is unable to comply with authoritarian requests (e.g. Ethereum) and offers strong privacy guarantees (none yet exist of material scale)

Tokenized securities

- Incremental: a protocol or set of smart contracts designed to comply with existing financial and legal systems, necessarily enabling those in power to control access and modify data of the protocol

- Anarchic: a completely new system for securities where the source of truth is not existing systems, but what is on the chain. This new system is unable to comply with authoritarian requests and sufficiently protects user privacy

Non-fungible tokens

- Incremental: just like tokenized securities where the token is only a pointer to the provenance (“true” version) of the asset. When the token and the asset are out of sync, a centralized entity is able to modify the ledger to match the token with the asset.

- Anarchic: the provenance of the asset is the token. The ledger is unable to comply with authoritarian requests and the privacy of users is preserved.

In each of these cases, there are possible benefits in adopting the incremental approach compared with current technologies. For example, an incremental approach to tokenized securities scales the technology behind securities while maintaining compatability with today’s systems. However, the incremental approach will never satisfy the requirements of crypto-anarchists because the incremental approach can always comply with authoritarian requests and does not necessarily (but could) offer privacy.

Conclusion

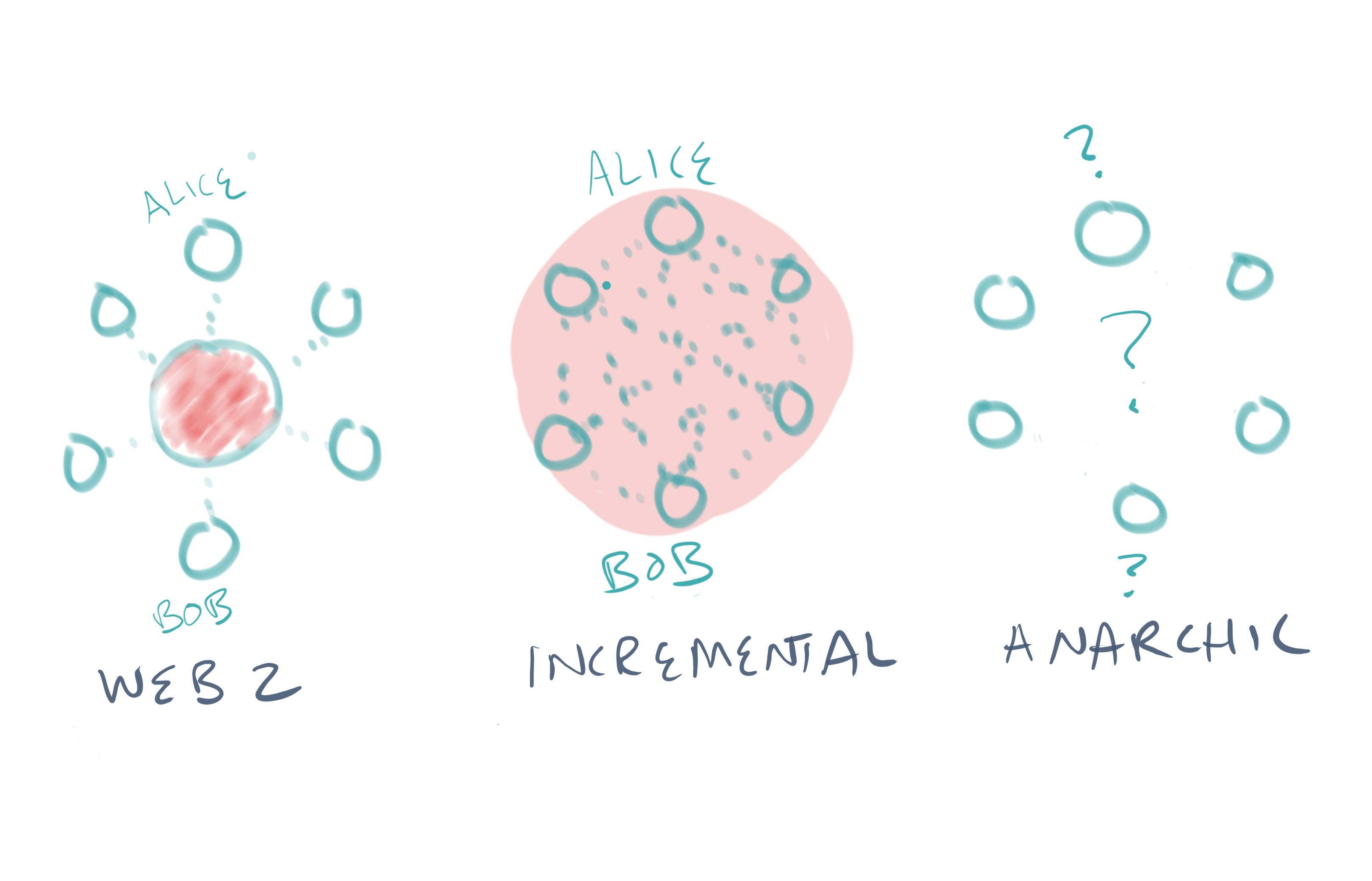

In sum, one can think of crypto projects as either crypto-incremental or crypto-anarchic. Both remove the middle-man omnipresent in today’s web2 systems, but differ in their abilities to comply with authoritarian requests and preserve privacy.

Crypto-incrementalists envision numerous applications of blockchain that improve efficiencies in existing systems, designing around current legal and financial systems. The protocols of crypto-incrementalists remove the middle-man but are not resistant to censorship. While their protocols may behave like decentralized networks, they are still able to comply with authoritarian requests. The crypto-incremental future does not look that different from today. Users may enjoy incrementally reduced fees, but no new freedoms.

The protocols of crypto-anarchists cannot comply with authoritarian requests. And they preserve the privacy and anonymity of its users. These requirements are hard to satisfy (as evidenced by Bitcoin’s poor privacy guarantees), and make certain use cases all but impossible (e.g. enterprise blockchains, tokenized securities) with legacy financial and legal systems.

Many of the most common debates in crypto reach an impasse because one party is a crypto-incrementalist and the other is a crypto-anarchist. Critics of EOS/IOTA/(anything that’s not Bitcoin) complain that it’s too centralized. If you are a crypto-anarchist, EOS would never satisfy your requirements. But if you’re a crypto-incrementalist, you may happily accept centralization for the faster transactions.

I believe crypto-incremental and crypto-anarchic projects can coexist. Where we see problems is in the widespread conflation of crypto-anarchic properties with crypto-incremental projects. Early crypto evangelists have been so successful in promoting censorship resistance and privacy that many assume that all crypto projects have or will have these properties. This is a dangerous misconception, as it’s highly unlikely (mostly impossible) that a project can go from crypto-incremental to crypto-anarchic. Crypto-incremental projects are simply not contenders for use cases that require crypto-anarchy, but many market themselves as contenders because the “value” of those use cases (e.g. unseizable money, permissionless platforms) is much higher than an incremental improvement to an existing system. We would do well as an industry to clarify.

- https://nakamotoinstitute.org/crypto-anarchist-manifesto/#selection-71.665-71.898 ↩

- https://bitcoin.org/bitcoin.pdf ↩

The False Dichotomy of Utility and Store of Value

By Qiao Wang

Posted July 5, 2018

There seems to be a growing belief that a cryptoasset doesn’t need to have high utility to be a good store of value (SoV), and conversely, it doesn’t need to be a good SoV to have high utility.

A more radical version of this even says that a good SoV cannot have high utility, and a high-utility asset cannot be a good SoV.

This leads to a popular, binary classification of tokens as being either a SoV or a utility token. For instance, people tend to classify Bitcoin as a SoV, and Ethereum as a utility token.

Origin of the Dichotomy

I suspect that the “SoV vs. utility” mental model stems from the realization that blockchains are characterized by two technical tradeoffs at the base layer:

- Decentralization vs. scalability: if you need to process a lot of transactions at the base layer, you may have to sacrifice decentralization, for instance by increasing the block size or by reducing the number of validators.

- Security vs. featurefulness: if you want the base layer to be featureful, for instance by introducing Turing-completeness, you may enlarge the attack surface.

Decentralization and security are important qualities of a SoV, while scalability and featurefulness create utility potential. Hence, SoV and utility are believed to be at odds with each other.

The velocity thesis, as reasoned from the equation of exchange M = T/V, further strengthens this view. As velocity (V) is inversely related to monetary base (M) in the equation, it is posited that utility tokens are unlikely to accrue value because users are unwilling to hold the asset.

Complementary network effect

Solutions to the aforementioned technical tradeoffs are beyond the scope of this discussion. However, we shall argue, from an economic point of view, that utility and SoV are not only a false dichotomy, but also form a synergistic relationship with each other, by exhibiting what we call a complementary network effect.

Complementary network effect refers to situations where increase in usage and value of one product increases usage and value of a separate product, which in turn increases usage and value of the original product.

For instance, an increase in the number of useful iOS apps make iOS devices more valuable, which in turn leads to more development of apps on iOS. An increase in the variety of available DVDs make DVD players more valuable, which in turn leads to more DVD production.

In the case of cryptoassets, we can view utility and SoV as two separate products of the same network. All else equal, more utility makes a cryptoasset a better SoV, which in turn increases utility.

This is not to say, for instance, that high utility will lead to a good SoV in the absolute sense. Rather, higher utility will lead to a better SoV in the relative sense. For instance, if an asset has a high inflation rate or low censorship resistance, utility not be sufficient to make it a good SoV, but will help it better store value than otherwise.

SoV as a complement to utility

Let’s first look at why SoV leads to better utility. To understand the symbiotic relationship between the two, we must first understand what they really are:

- An utility asset is one that we exchange for another product or service.

- A SoV asset is one that we hold so that at some point in the future we exchange it for another product or service.

The key insight here is that utility involves exchange, and an exchange involves both a buyer and a seller. If you are a buyer, you may not care about whether the utility asset you are giving up is a good SoV. In fact, if you had a choice between spending a good SoV and a bad SoV, you’d probably want to spend the bad one. But the seller, who is your counterparty, prefers to accept a good SoV, because obviously they are the one who will hold the asset.

Some argue that sellers don’t care because if you pay them a bad SoV, they may be able to immediately dump it for a good SoV. But as a matter of fact that additional trade comes with a cost, be it a financial, temporal, or mental, and thus is less preferable.

I have travelled to at least 20 developing countries in Latin America, Eastern Europe, Africa, and Asia, and almost everywhere I go the USD is at least as widely accepted as the local currency. Why is the USD so popular even if it’s not a legal tender? Why do locals prefer it over some other international currencies? Because the Federal Reserve is the most capable central bank in the world at maintaining the value of its currency.

Electoral power

A second-order effect of being a good SoV is that, if a critical mass of people hold the asset in a democratic country, it makes it very hard for the government to ban or otherwise suppress the asset, which clears the path for utility adoption.

In January 2018 South Korean Justice Minister caused an uproar after he called for a ban on cryptocurrency exchange in a press conference, and subsequently softened his stance. Some estimates put cryptocurrency ownership in the country as high as 33 percent of the adult population. Arguably, South Korea has reached the critical mass of electoral power.

Utility as a complement to SoV

Here’s a thought experiment. Suppose that a cryptonetwork is worth $100,000 and there are 10 users. Then on average each user would have to hold $10,000 worth of tokens at any point in time. Maybe that’s too much, and so they would want to dump the tokens. Suppose now that there are 10,000 users in the $100,000 cryptonetwork. Then the average user would only hold $10 worth of tokens, and happily do so for convenience and without worrying too much about the impact of their token holding on their overall portfolio.

This is the intuition behind usage creating value. But there is more to it. An increase in utility actually improves the very properties of a good SoV, such as liquidity, security, decentralization, and intersubjective beli ef.

Liquidity

Utility increases liquidity because people need to trade the asset in order to use it. For instance, imagine that prediction markets and gambling platforms, which are prohibited by many governments around the world, become wildly successful on a censorship-resistant platform like Ethereum. Then people will have to exchange fiat for Ethers in order to use those apps, and then exchange Ethers for fiat to cash out.

Liquidity is especially powerful as it is self-reinforcing. The more liquid an asset has been historically, the more speculators it will attract.

But why is liquidity important for a SoV in the first place? As previously defined, a SoV is an asset that we hold so that at some point in the future we can exchange it for another product or service. If liquidity of the asset is lower, then the cost of exchange is higher, and hence by definition the asset would be a worse SoV.

Security

Miners and stakers need economic incentives to secure the network. They can charge users through transaction fees or holders through inflation. And here’s the elephant in the room. An inflationary monetary policy obviously leads to a worse SoV. So if the network doesn’t want incentives to come from inflation then they must come from transactions, i.e., utility. But if there is no transaction in a deflationary cryptonetwork, who will secure it?

The perfect example of this is Bitcoin, which currently is the best SoV cryptoasset. As its inflation trends to 0, miner rewards will have to come from transaction fees. If they are no longer incentivized to secure the network due to the lack of block rewards and transaction fees, then Bitcoin will obviously lose its SoV status.

Decentralization

The activation of Segwit showed the world that users operating full nodes had tremendous governance power even if the majority of miners wanted a different direction. By extension, it demonstrated that the more utility a network has, the more likely it is to have a diverse set of stakeholders, none of whom can change the rules of the network on a whim.

Would Bitcoin have been equally immune to changes during the first couple of years, when it had many fewer users with skin in the game, and therefore less checks and balances?

How decentralized a cryptonetwork is ultimately boils down to how immune it is to oligarchs attempting to change the rules, or to change states not according to the rules. This is a crucial property of a SoV because a good SoV is one whose monetary policy is credible, transactions cannot be censored, and balances cannot be stolen, by one or few malicious actors.

Intersubjective belief

The familiarity principle is a phenomenon by which mere exposure to a particular thing makes people like it more. An obvious real-world application of this psychological trick is advertising. Another example is that people tend to invest in domestic companies as they are less exposed to international news. If we use Bitcoin as a payment rail or Ethereum as a dapp platform on a day-to-day basis, we could develop a subconscious attachment to them.

I debated internally for a long time whether or not this is relevant to SoVs, as this is getting into the realm of evolutionary psychology or even philosophy. Then I asked myself a few questions.

- Why is gold almost two orders to magnitude more valuable than Bitcoin even if the latter is almost strictly better?

- How did Nixon successfully get the USD off of Bretton Woods?

- Why has ETH been more valuable than ETC ever since the fork even if the latter maintained immutability?

The answer may be intersubjective belief, a term borrowed from Sapiens. “Intersubjective belief is something that exists within the communication network linking the subjective consciousness of many individuals. If a single individual changes his or her beliefs, or even dies, it is of little importance. However, if most individuals in the network die or change their beliefs, the inter-subjective phenomenon will mutate or disappear.”

Religion is a intersubjective belief. Capitalism and democracy are in many ways intersubjective beliefs. Money is also an intersubjective belief.

- The value of gold does not only stem from its durability and scarcity, but also benefits from a strong shared belief that has been built through thousands of years of human exposure.

- America and the world continued to use the USD without much turmoil after it got off gold, as people have been used to transacting reliably using the same pieces of paper during the several decades prior.

- ETH has been more valuable than ETC partly because ETH proponents were more trusted by the community and thus more influential on the intersubjective belief.

Empirical Evidence Against the Velocity Thesis

It’s perfectly fine to reason about the velocity thesis using common sense, for instance, by saying something along the lines of “more people willing to hold the asset reduces circulating supply thereby driving price up”. However, it’s highly handwavy that many proponents of the velocity thesis use the tautological equation of exchange M=T/V to conclude that:

- Utility does not lead to value.

- Value is suppressed by velocity.

This is because the growth of velocity (V) could merely be a consequence of higher utility (T), rather than users’ lower desire to hold the asset which would suppress value (M).

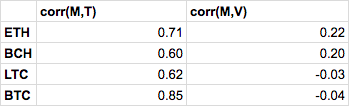

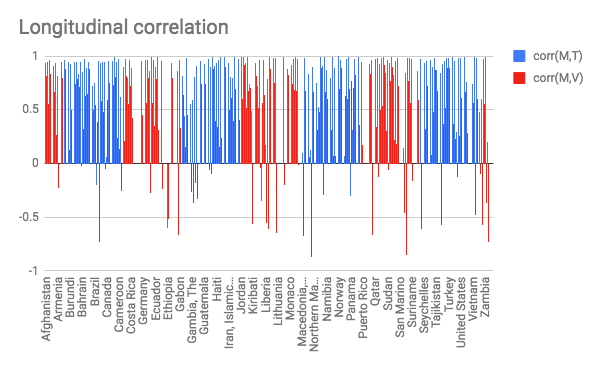

Indeed, empirical evidence (data source: coinmetrics.io) shows that:

- Utility (T) has historically been strongly correlated to value (M).

- Value (M) has historically been uncorrelated, or evenly weakly positively correlated to velocity (V).

One could argue that the velocity thesis does not apply in the early, speculative phase, but will eventually hold at equilibrium. But since the equation of exchange is borrowed from the macroeconomic world of fiat currencies to reason about the microeconomic world of cryptocurrencies, which by the way is completely nonsensical, a natural question one would ask is, does the velocity thesis even hold for fiat currencies?

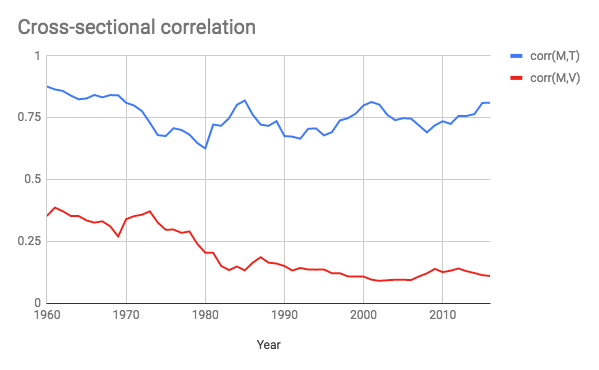

Unsurprisingly, both cross-sectional and longitudinal studies (data source: worldbank.org) show that once again:

- Utility (T) is strongly correlated to value (M).

- Value (M) is positively correlated to velocity (V).

In other words, the empirical evidence in both crypto and fiat is:

- Consistent with our reasoning that utility and SoV are synergistic with each other. It does not prove our thesis, but is coherent with the latter.

- Inconsistent with, and therefore rejects, the null hypothesis that velocity diminishes value.

Conclusion

If the technical tradeoffs described earlier can be solved, then there is no reason to believe that SoV and utility cannot make each other better. Thanks to the complementary network effect, SoV properties such as sound monetary policy and security drive more users to transact on the network and developers to make network more usable, which in turn reinforces the SoV status of the cryptoasset.

That’s a big “if”, of course.

However, we should not underestimate the ingenuity of the engineers who are working on these problems. L2 scalability solutions that also preserve L1 decentralization on their way to production. Ethereum had egregious security issues on the application layer, but these issues don’t seem to be unsolvable with better coding practices, and the base layer has been remarkably issue-free so far, in spite that many believed otherwise back in 2014.

Bitcoin Governance

By Pierre Rochard

Posted July 8, 2018

My speech at the Chain-In conference that this medium post is based on:

Why do we care?

Bitcoin’s governance matters because Bitcoin is the first successful, most liquid, and most widely known crypto-currency. In the words of Michael Goldstein, “Sound money is a foundational pillar of civilization, and Bitcoin restores this powerful tool for social coordination.” If Bitcoin’s governance model is flawed, it could prevent Bitcoin from reaching its full potential. If Bitcoin’s governance is flawed, Bitcoin’s stakeholders should work to fix it.

Conversations regarding Bitcoin’s governance tend to focus on who the decision makers ultimately are, perennial candidates include miners, nodes, and investors. The purpose and mechanics of governance are often just implied or even disconnected from reality. Views on the efficacy of past governance are often driven by who “won” or “lost” a specific decision, rather than the adequacy of the decision making process itself.

What is Bitcoin governance?

Bitcoin governance is the process by which a set of transaction and block verification rules are decided upon, implemented, and enforced, such that individuals adopt these rules for verifying that payments they received in transactions and blocks fit their subjective definition of “Bitcoin”. If two or more individuals adopt the same set validation of rules, they form an inter-subjective social consensus of what “Bitcoin” is.

What is the purpose of Bitcoin’s governance?

There is a wide range of views regarding what the purpose of Bitcoin’s governance should be. What outcomes should governance optimize for?

- Matt Corallo argues that trustlessness is the most important property of Bitcoin. Matt defines trustlessness as “the ability to use Bitcoin without trusting anything but the open-source software you run”. Without the property of trustlessness, all other positive outcomes are jeopardized.

- Daniel Krawisz argues that maximizing the value of a bitcoin is what governance de facto optimizes for. Daniel states that “the general rule about Bitcoin upgrades […] is that upgrades which increase Bitcoin’s value will be adopted and those which do not will not.”

In the context of Bitcoin’s governance, these two views mirror the classic divide between deontological and consequentialist ethics respectively. I favor Matt’s deontological approach of focusing on trustlessness. Throughout monetary history, from ancient coin producers to modern central banks, trusting others to produce money has resulted in abuse of that trust. Compromising on trustlessness could help the Bitcoin price find a local maximum, at the expense of finding a much higher global maximum. Furthermore, there is no evidence that Bitcoin’s price has been correlated with upgrades to the Bitcoin protocol. Perhaps Bitcoin’s fundamental value is affected by upgrades, but Bitcoin is so illiquid and volatile that the price does not reliably reflect fundamental value. If we can’t observe the consequences of an upgrade on Bitcoin’s value, the consequentialist approach seems inadequate.

Before we can evaluate the current Bitcoin governance process against the stated goals of maintaining trustlessness or increasing the value of Bitcoin, we should attempt to define how the current Bitcoin governance process actually works.

How does the current Bitcoin governance process work?

The Bitcoin governance process maintains a set of verification rules. At a high level, this long set of verification rules covers syntax, data structures, resource usage limits, sanity checks, time locking, reconciliation with the memory pool and main branch, the coinbase reward and fee calculation, and block header verification. Amending these rules without tradeoffs is no easy feat.

Most of these rules were inherited from Satoshi Nakamoto. Some have been added or amended to address bugs and denial-of-service vulnerabilities. Other rule changes occurred to enable innovative new projects. For example, the new Check Sequence Verify opcode was added to enable new scripts.

Research

Every rule change begins with research. For example, SegWit began with research into fixing transaction malleability. Transaction malleability had become a serious issue because it prevented the Lightning Network from deploying on Bitcoin. Industry and independent researchers collaborated on what eventually became SegWit.

Critics have pointed out occasional disconnects between what researchers want to research, user expectations, and what is good for the network’s properties. Additionally, academic computer scientists prefer “scientific simulations” over “engineering experiments”. This has been a source of tension in the research community.

Proposal

When a researcher has discovered a solution to a problem, they share their proposed changes with other protocol developers. This sharing could be in the form of an email to the bitcoin-dev mailing list, a formal white paper, and/or a Bitcoin Improvement Proposal (BIP).

Implementation

A proposal is implemented in the node software by the researcher(s) who proposed it, or by other protocol developers who are interested in it. If a researcher can not implement a proposal, or the proposal does not attract favorable peer review, then it will linger at this stage until it is either abandoned or revised.

While this may give the impression that the contributors to Bitcoin protocol development can veto a proposal, a researcher can make their case to the public and route around existing developers. In this scenario, the researcher is at a disadvantage if they lack reputation and credibility.

Another problem at the implementation phase is that the maintainers of the reference implementation will not merge in an implementation if it is widely seen as contentious by the Bitcoin protocol developers and the wider Bitcoin community. The reference implementation’s maintainers have a deliberate policy of following consensus changes rather than trying to impose them. The C++ reference implementation, hosted at github.com/bitcoin/bitcoin, is the direct successor of Satoshi’s codebase. It continues to be the most popular Bitcoin node implementation due to its maturity and reliability.

To circumvent the reference implementation’s maintainers and make consensus changes regardless is as simple as copying the Bitcoin codebase and releasing the proposed changes. This happened with the BIP-148 User Activated Soft Fork (UASF).

A proposal to change validation rules can have a softfork or a hardfork implementation. Some proposals can only be implemented as a hardfork. From the perspective of pre-fork nodes, a softfork implementation is forward-compatible. With a softfork, the pre-fork nodes do not need to upgrade their software in order to continue validating the pre-fork consensus rules. However, these pre-fork nodes are not validating rule changes made by the soft-fork. From the perspective of pre-fork nodes, a hardfork is notforward-compatible. Pre-fork nodes will end up on a different network as post-fork nodes.

There has been controversy about the effects of hard and softforks on the network and users. Softforks are seen as being safer than hardforks, because they do not require an explicit opt-in, but this can also be seen as coercive. Someone who disagrees with a softfork must hardfork to reverse it.

Deployment

Once implemented in the node software, users must be persuaded to use the node software. Not all node users are equal in their importance. For example, “blockchain explorers” have more power as many users rely on their node. Additionally, an exchange can determine which validation rule set belongs to which ticker symbol. Speculative traders, large holders, and other exchanges provide a check on this power over ticker symbols.

While individual users may signal on social media that they are using a certain version of node software, this can be sybil attacked. The ultimate test of consensus is whether your node software can receive payments that you consider to be bitcoins, and you can send payments that your counter-parties’ node software considers to be bitcoins.

Softforks have an on-chain governance feature called BIP-9 Version bits with timeout and delay. This feature measures miner support for softforks on a rolling basis. Miner support for proposals is used as a proxy measure for the wider community’s support. Unfortunately this proxy measure can be inaccurate due to mining centralization and conflicts of interest between miners and users. On-chain “voting” by miners also perpetuates the myth that Bitcoin is a miner democracy, and that the miners alone decide on transaction and block validity. BIP-9 is useful to the extent that we recognize and accept the limitations of proxy measurements.

Enforcement

Changes to the validation rules are enforced by the decentralized p2p network of fully validating nodes. Nodes use the verification rules to independently verify that payments received by the node operator are in valid Bitcoin transactions and are included in valid Bitcoin blocks. Nodes will not propagate transactions and blocks which break the rules. In fact, nodes will disconnect and ban peers which are sending invalid transactions and blocks. As StopAndDecrypt put it, “Bitcoin is an impenetrable fortress of validation.” If everyone determines that a mined block is invalid then the miner’s coinbase reward + fees is worthless.

The role of miners is to provide a proof of publication function (often referred to as “timestamping”) with a difficulty-adjusted proof-of-work for transaction ordering. The amount of hashrate provided is based on the cost of hardware and electricity on one hand, and revenue from the coinbase reward + fees on the other hand. Miners are mercenaries, and in the past they have provided their services without full rule validation. Due to mining centralization, miners can not be trusted to enforce the validation rules on their own.

Has the current Bitcoin governance model resulted in more trustlessness?

In my opinion, the current Bitcoin governance model has prevented a degradation of trustlessness. The dramatic increase in on-chain Bitcoin transactions over the past 5 years seemed to have no end in sight. If Bitcoin’s governance model had not been resistant to last year’s miner signalling for a doubling the maximum block weight, a precedent would have been set of valuing transaction throughput above trustlessness.

Has the current Bitcoin governance model resulted in upgrades that increase Bitcoin’s value?

I think it’s impossible to establish a causal relationship. The price is much higher than it was 2 years ago, but it seems to be an endogenous process driven by trader psychology, not technological fundamentals. Regarding fundamentals, it’s undeniable that Bitcoin’s governance has delivered on consensus changes which the Lightning Network depends on to operate. I’ve been experimenting with establishing channels and making Lightning payments: there is no doubt in my mind that LN increases Bitcoin’s value.

The Bitcoin Risk Spectrum

Nik Bhatia

Posted July 9, 2018

- 1/4 The Bitcoin Second Layer

- 2/4 The Time Value of Bitcoin

- 3/4 The Bitcoin Risk Spectrum

- 4/4 The Lightning Network Reference Rate

Bitcoin is already a reserve asset. It is the world’s first true example of decentralized digital scarcity, and its elegant, predetermined supply schedule reinvents monetary policy. Its value is recognized by millions of people who own bitcoin as a savings vehicle, speculative investment, or currency hedge. Bitcoin is a reserve asset because millions of people own it as one. Its next step is to transition from a reserve asset to a functioning reserve currency by unlocking the bitcoin capital market. Lightning Network’s arrival finally allows us to assign time value to bitcoin, and we can begin building bitcoin’s capital market from first principles.

Lightning Network

HTLCs are financial agreements with two important properties that eliminate reliance on trusted third parties. Firstly, the contracts have an embedded call option on the counterparty’s bitcoin which dissuades theft. Secondly, the contracts have an expiration, which prevents balances to be held in limbo to perpetuity. These two properties remove counterparty risk but instead introduce payment channel management risk. Routing Lightning payments is the equivalent of a short-term bitcoin lease and allows the router to earn fees; these fees can be used to calculate interest earned on bitcoin staked to Lightning payment channels.

Traditional Capital Markets

Traditional capital markets have a risk spectrum: generally speaking, higher variance of returns is positively correlated with a higher expected return. More risk, more reward. It is important to note that risk-free rates are entirely conceptual and theoretical. They are simply a matter of convention to facilitate financial theoretical research and improve communication. Therefore, this article is an attempt to discuss and derive bitcoin-native financial theory, including how bitcoin can be reconciled against other assets. Bitcoin is still trillions of dollars of market capitalization away from becoming a legitimate alternative to other deep capital markets like the ones denominated in US Dollars, Euros, Yen, Pounds, and Yuan. Before we dissect bitcoin’s risk spectrum, let’s take a look at that of the US Dollar to get a sense of which aspects bitcoin should copy and which it should reinvent.

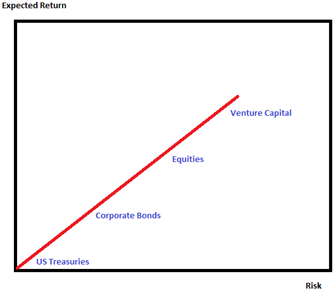

US Dollar Risk Spectrum

Why is the US Dollar the world’s reserve currency? There are many reasons including geopolitical and economic prowess, but one of the reasons is the depth of its capital market. There are over $100 trillion in bond and equity securities, allowing owners of US Dollars to easily find a home for them. Its capital market can be viewed as a risk spectrum, with risk on the x-axis and expected return on the y-axis.

US Dollar Risk Spectrum

US Dollar Risk Spectrum

The first point (illustrated) on the risk spectrum is US Treasury debt. Financial theory requires a risk-free asset to establish baseline interest rates, and currently that asset is US Treasuries. The obvious flaw of this financial theory is that US Treasuries are not truly risk-free. They have default risk, albeit appropriately characterized by market as the lowest possible default risk that an investor can attain. (Many sovereign bonds now have yields lower than yields in the United States, but those bonds are not denominated in US Dollars. This article is written only comparing bitcoin to the US Dollar).

The second point is corporate bonds. Companies issue fixed obligations at a spread to US Treasuries; for example, this year Walmart issued a 5yr bond at 5yr Treasuries plus 0.60% and General Motors issued a 5yr bond at 5yr Treasuries plus 1.37%. Each of these companies used the 5yr US Treasury as a reference rate. Investors consider the risk premium, or creditworthiness, of each company relative to Treasuries. We can see from this example that bond investors view Walmart as more creditworthy than General Motors because Walmart borrows at a lower spread to Treasuries. This is why reference rates are considered an anchor for debt capital markets, because they more easily allow for relative value comparisons.

Further along the risk spectrum are investments with higher risk profiles, such as publicly traded equities and venture capital funds. Theoretical formulas for the expected return on equities usually include a combination of the risk-free rate and the company’s risk premium. Venture capital investors will seek an even higher return because the probability of principal loss is perceived to be higher than that of public equities. Theoretical risk premiums are added to each subsequent point of the risk spectrum, all anchored from the risk-free rate.

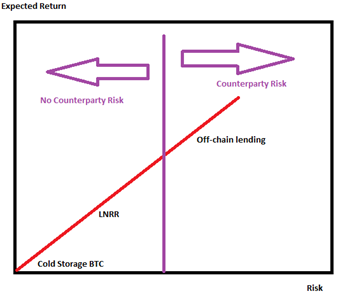

Bitcoin Risk Spectrum

Bitcoin’s capital market should be designed from first principles because its final settlement does not require trusted third parties. Final settlement of the US Dollar has counterparty risk because deposits are considered a liability on banks’ balance sheets. Holders of US Dollars would rather face the US government as a counterparty rather than banks, so they prefer to purchase US Treasuries with their deposits. Either way, the final settlement has counterparty risk. Additionally, the US Dollar itself depends on a single nation and has a single entity controlling monetary policy in a discretionary way; bitcoin avoids both of these risks. Let’s take a look at Bitcoin’s risk spectrum.

Bitcoin Risk Spectrum

Bitcoin Risk Spectrum

The first point (illustrated) on Bitcoin’s risk spectrum is bitcoin held in cold storage. The analogy commonly used for cold storage is a gold bar held in your hand. There is no counterparty risk; the risk is its storage and security, much like if you had possession of physical gold. Skilled storage and security practices make loss less likely, and the advent of robust multisignature solutions further reduces risk. Private key management anchors the bitcoin capital market much like the timeliness and consistency of the US government paying back its debt obligations anchor the US Dollar’s capital market. The expected return on cold storage bitcoin is at best zero and is actually negative if you consider that storage costs and on-chain transaction costs are non-zero.

I am proposing that the second point on Bitcoin’s risk spectrum should be LNRR, the Lightning Network Reference Rate. Routing fees earned on bitcoin staked to Lightning payment channels can be expressed as an interest rate. The rates received on the payment channel or node level can be hashed and cryptographically provable. Node operators can opt-in to publish realized interest rates on their capital. If a consensus can be reached on an interest rate calculation protocol, capital providers can publish interest rates in an open and transparent way. Positive interest rates will attract bank-like entities that believe they can earn positive return using effective payment channel management and security techniques. Some bitcoin previously held in cold storage will seek the income attainable in Lightning Network, the first ever example of an opportunity cost tradeoff in bitcoin that doesn’t require additional counterparty risk. Bitcoin staked to Lightning is the most unique income producing asset in all of monetary history: income with zero counterparty risk. The historical implications of this on capital markets are tremendous.

A huge leap in risk exists between the second and third point on Bitcoin’s risk spectrum. The first two points, as we have established, have various security and management risks but no counterparty risk whatsoever. Real world lending of bitcoin has genuine counterparty risk, whether using exchange-based lending platforms or other forms of direct lending. In theory, these rates of borrowing should be higher than LNRR, and capital providers could use LNRR to make relative value decisions between bitcoin leasing via Lighting and off-chain bitcoin lending. Any real world lending will not have bitcoin’s blockchain as security. Lenders will need strong contracts in jurisdictions with strong rule of law to ensure repayment of capital, just as they do with fiat currencies. Complete loss of principal remains.

Conclusion

I am increasingly optimistic that we are close to seeing Lightning Network wallets provide a way to calculate interest earned via routing fees. Lightning development is accelerating and the total bitcoin staked to payment channels is increasing accordingly. The time value calculations that we are on the verge of realizing will underpin the entire bitcoin capital market. It will not happen all of a sudden. Node operators will need to cryptographically prove interest earned over a long enough time horizon to attract larger sums of capital to Lighting Network. Wallet infrastructure and security both still need a lot of improvement, especially as UX leaves the command line and enters the GUI phase. I am eager and excited to hear from the Lightning community on how we can achieve the first step on the path to reserve currency: interest rate and time value calculations.

Cryptocurrencies are money, not equity

Developer incentivization and the power of holders

By Brendan Bernstein

Posted July 22, 2018

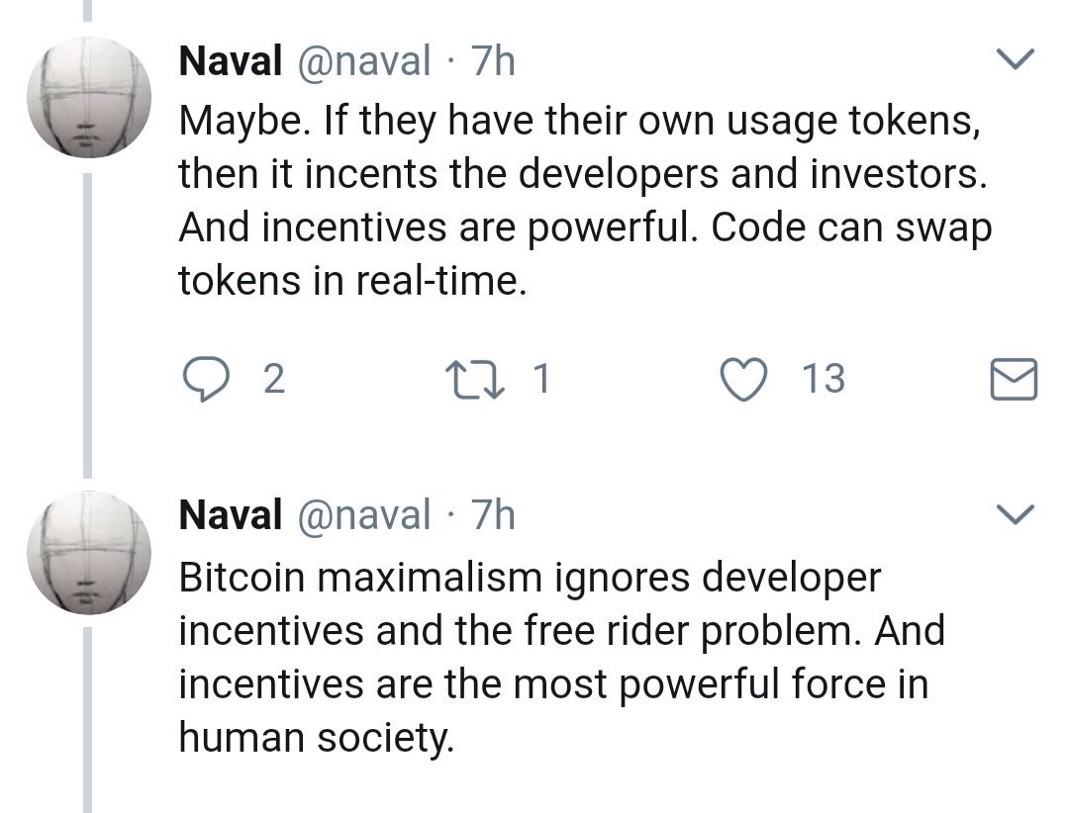

Naval recently incited a debate regarding developer incentivization and the value of holders. It spurred a number of responses and a fruitful discussion. This issue has just about been exhausted. But instead of banging my head against the wall in frustration, I figured I’d add my two cents and meander on the axiomatic issues in the cryptocurrency space that this revealed.

There are two questions Naval surfaced: (1) What’s the value of holders? and (2) How to incentivize developers?

Naval’s contention stems from a deep issue: the tech investing ethos in a space with monetary assets. The two are diametrically opposed. Like Ethereum and multi-sigs. Reconciling this matter should also answer his two questions.

The goal of this post is to remove these notions from your brain. I can’t promise it will work in its entirety…you may still eat vegetables after this. But hopefully you can rid yourself of the naive comparison of tokens to traditional startup investing and begin to understand the pivotal role investors play. Altcoin rehab, if you will.

Table of Contents:

i) Cryptocurrencies are money

ii) How cryptocurrencies capture value

iii) Crucial role of investors in value capture

iv) Investors run the show

Cryptocurrencies are Money, not Equity

The fundamental fallacy is treating cryptocurrencies like equity when in reality they are money. Sure, most “technical whitepapers” have no mention of money whatsoever. But given we’re talking about incentives, why would they?

Pretending tokens are equity-like differentiates their token from Bitcoin. Instead of appealing to the monetary nature, a whitepaper can propose notions that appeal to traditional equity investors. But really, all unpegged cryptocurrencies are money and need to be understood that way.

The majority have a stated use case as a medium of exchange within a quasi-decentralized economy. To many “technologists” dismay, that is economics speak.A medium of exchange and a currency is very different than equity

If it sounds like I’m just being petty, I promise I’m not. It’s a small distinction to some, but failure to make this crucial distinction will lead to a host of problems.

Value Creation != Value Capture

The value of any business, centralized or not, is the value of services it provides to its end user. But that does not necessarily mean that the business captures that value. The best equity investments both create and capture the most value.

An investment’s value is based on the market size and % of that market investors capture. The two are often times independent.This has traditionally been an issue for open source projects. Open source technologies, like Linux for example, have added immense value to the world but Linux itself is not able to capture it.

The freedom, security, flexibility and accountability of open source often is considerably better than proprietary alternatives — but capturing that value has often been futile. Tokens were supposed to be the white knight for open source developers of the world. Finally, developers could both open source their code and make money.

How to Capture Value?

Remember equity? An instrument startups used to raise money with before the millennials took over. Equity is a contract that gave its holders recourse to the balance sheet and liquidation value of a company. To oversimplify a little, equity investors are generally investing in increasing cash flow. But if tokens are not equity, what are buyers really investing in?

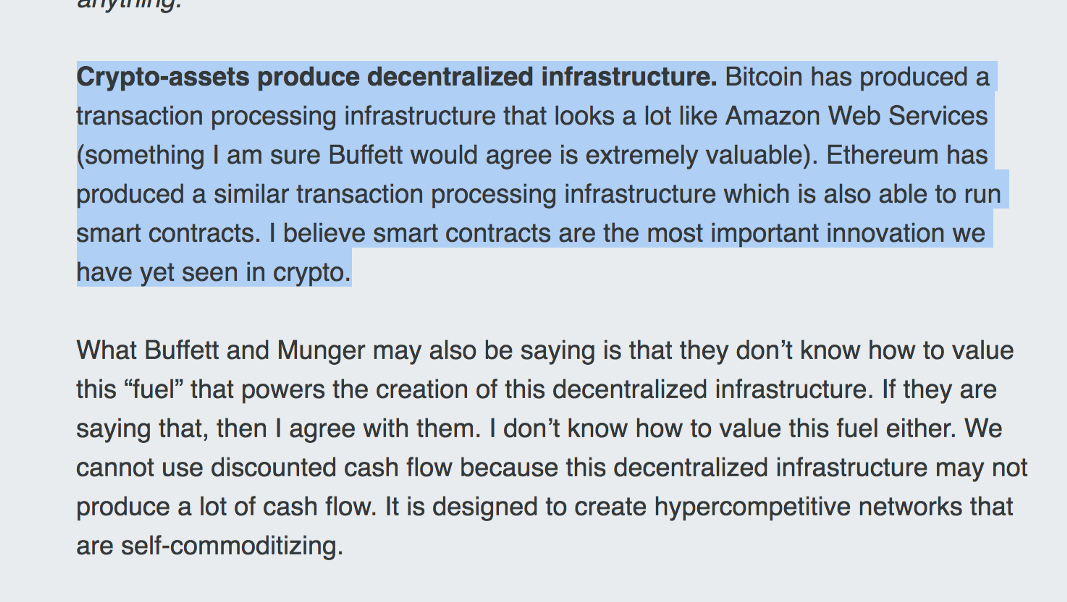

According to Fred Wilson (whom I have great respect for), the answer is “decentralized infrastructure”.

I think that Fred and others are directionally correct. But where I think some investors are going wrong is equating an equity-like infrastructure investment with a token and monetary investment. Keyword here being token.

Here’s my take on what’s happened:

Step 1: Convince investors that tokens are equity-like.

Step 2: Convince investors that the protocols will be “fat”.

Step 3: Create an “infrastructure” protocol.

Step 4: Sell to investors.

Step 5: Profit.

Tokens do indeed power (quasi) decentralized infrastructure, but that doesn’t mean that they necessarily capture any of the value they produce. Like our poor friend, Linux.

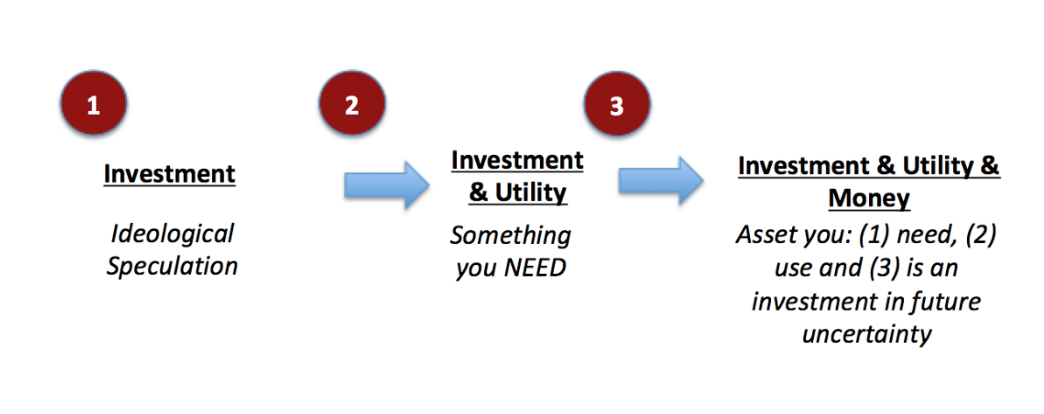

Value capture for a money boils down to supply and demand. MV = PQ (That’s the “equation of exchange” for the uninitiated.), for example, is interesting to the extent it captures this dynamic. It’s a helpful mental construct. But like wet dirt, it should not be used in a vacuum.

The next assertion may feel a little bit unpleasant as it starts to tug on the part of your brain where the aforementioned memes have their stranglehold. But bear with me and resist the urge to regress.

The market cap of anything is the amount of wealth held in it. It is the amount of units * the price of the asset. AAPL being worth $700bn means that $700bn of wealth is held in the stock. Gold being worth $7tn, means that $7tn of wealth is held in gold. BTC being worth $150bn means that $150bn of wealth is held in the token. The velocity discussion is just another way to elucidate this mechanism. For stocks and tokens alike, the more wealth that is held, the more it goes up in price.

Intuitively, this should make sense. If you buy something and sell it immediately that negates the benefit to price from buying it in the first place.

Investors in the equity world use KPIs and multiples to map value creation to value capture: LTV / CAC, DAUs and EBITDA multiples. The framework is that as “usage” increases, so does the valuation. The KPIs help to abstract this into digestible metrics. But these same mental models don’t belong in the cryptocurrency realm.

KPIs tend to work for equity because usage generally maps to cash flow. Tropes like follow the developer activity work for centralized platforms because they tend to generate more cash flow the more people work on it. Centralized aggregators — Google, Facebook, Netflix — need to garner a tremendous amount of usage for the positive feedback loops of value creation to kick into effect.

As a business’s cash flow increases, there’s a greater incentive to hold its stock because of the legal recourse to cash flow and concomitant increase in dividend yield / liquidation value. If the market cap was $100bn, and cash flow increases from $10bn to $20bn, yield doubles and the price should double as a result to bring the yield back in line with the market. Investor demand to hold increases to capture this yield. But even in the absence of price increases, an investor can still do well if the dividend increases.

There’s a tacit assumption in cryptocurrencies that the same link above — from usage to value creation — will hold true. That KPI improvement — say usage of Filecoin’s network for example — will lead greater wealth held in the cryptocurrency. But the biggest difference between equity and money comes down to the incentive to hold.

The Behavioral Nature of Money

Unlike equity, cryptocurrencies and money have absolutely no recourse to cash flow, no preferential rights, no dividend stream and no pro rata share of liquidation value. Money is not a productive asset.

If you are holding a money, you’re betting on the market cap staying the same or increasing in the future (hence, storing your value). Given the above framework, it’s a bet on either the same amount of, or more wealth, being held in the asset later on. But unlike equity, because money is not a productive asset, holding money makes you entirely dependent on the actions of others.

To the best of my knowledge you cannot consume tokens. At least, I hope you aren’t. The only way for them to get you anything in return is if other people accept it in exchange for consumable goods and services.

Money has value because everyone believes it has value. Absent the shared belief, there’s no intrinsic value in holding a money.

Every time you’re using a money, somebody is demanding the monetary asset from you. And given the monetary asset is not consumable, the only way somebody would demand it is if they also think they can use it to demand other goods and services. Money only has value because of the optionality it confers on holders, which is a byproduct of other people’s demand for money.

Investors bootstrap a new currency: Cryptocurrency “Regression Theorem”

Hopefully by now you understand that money and equity couldn’t be more different. Using the same mental models to invest in both is going to end disastrously. But you’re probably left wondering how any monetary asset can accrue value in the first place if it’s not just based on “usage”.

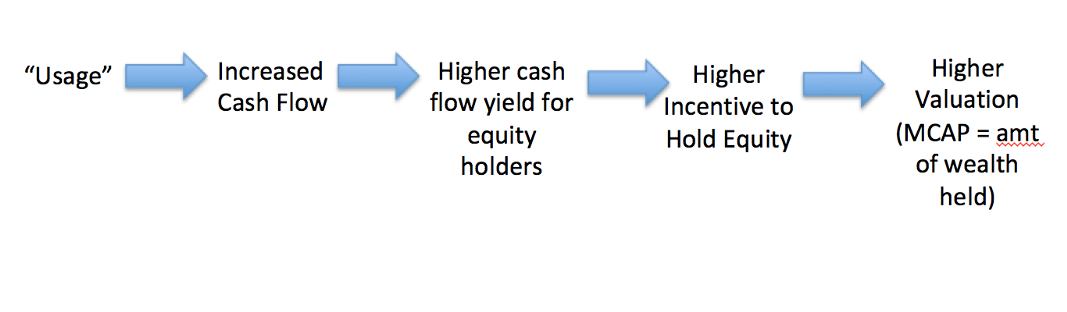

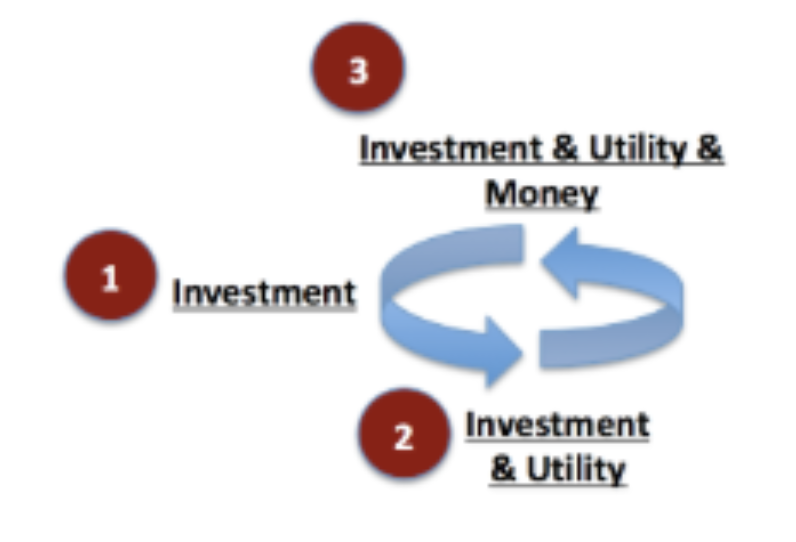

Below, I propose a cryptocurrency “regression theorem” — a three step process towards crypto-asset monetization (Mises coined the regression theorem for his theory on the origins of money) . This isn’t meant to describe the origins of money, but instead how a crypto-asset will accrue value and win based on where we stand today.

The only cryptocurrencies that accrue value will be those that traverse the three steps above. Before I shock you even more by saying this can only occur with one asset, let me introduce you to this concept.

First a cryptocurrency begins as an asset held for speculative purposes. Early investors in a new money are rewarded handsomely if it’s adopted. Initial holders don’t have many opportunities to exchange the asset for goods and services — with significant risk comes a commensurate reward.

Step 2 is the introduction of a narrow form of utility — ICOs for ETH and Silk Road for BTC are examples. I’d also consider BTC usage as a SoV for citizens in countries with hyper-inflating currencies an example today. It almost feels dirty using the word utility in this concept because dApp platform promoters have stolen it from us. But utility in this regard does not necessarily mean “dapp utility”. It just reflects the progression from a purely speculative asset to one with speculative demand and narrow usage.

Third and finally, it becomes money: an asset you need, use and is also an investment in future uncertainty. A true money isn’t just an asset with narrow utility, but one that you cannot survive without. It’s an investment in future uncertainty and a vehicle to transfer wealth across space and time. It’s like Star Trek. But with money.

There’s an important and under-appreciated time component. The key distinction between an SoV and MoE is that an SoV is a MoE in the future. To invest in the future optionality, investors today must have confidence that investors in the future will demand the same monetary instrument for savings. And investors in the future also require the same guarantees. The process ends up becoming self recursive and non-linear.

Investment in step 1 is predicated on the asset progressing to step 2. And prospective investors in step 2 will buy only if they think the asset can move to step 3. Thus, investors in step 1 will only enter if they believe it can complete the full loop. If there’s a leak anywhere in this process, it cannot start.If investors in step 1 don’t ultimately think it has the ability to become a widespread money, it should never be able to get off the ground in the first place.

This is why long term credibility of monetary policy is imperative. Uncertainty suffocates this process as the value of a money rests on the confidence of holders in the future nature of the monetary asset. Holders today won’t make a bet on holders in the future if they don’t know what monetary factors those future holders will be subject to.

But so many cryptocurrencies have defied the “cryptocurrency regression theorem” you say. Well yes, today, this process is extremely leaky. But it’s because it’s behavioral in nature and the behavior of most investors is akin to a drunk person at a yard sale. They’re buying everything regardless of price and utility.

Most investors today still mistakenly think cryptocurrencies will accrue value like a stock and that their investment success hinges on a mere transition from step 1 to 2. However, as cryptocurrencies attempt to progress through this process, usage alone will not be enough to sustain a cryptocurrency’s valuation. The transition to step 3 must occur. And those who usher others on the cryptocurrency monetization ride through this process are the long term investors and holders. Not a free rider in my book.

Why is step 2 not sufficient? There’s a widespread notion that money is valuable because it is useful as a medium of exchange, when in reality the opposite is true. If money were simply used as a monetary medium, but not held as savings, any increase in its value would immediately be negated as the user sells out of the asset. The only way the market cap of a money can increase is if people hold more wealth in an asset.

Since 1950s, usage and adoption of the USD increased dramatically. Used as a world reserve currency, the mechanism for all oil trade, and the preferred currency for large scale Equity ICOs (I mean IPOs), adoption has taken off. But since 1970 gold has still gone up 6x vs the USD. Clearly “usage” is not the only determinant of a money’s long term value.

Gold price vs USD

Gold price vs USD

Thus a transition to the third step is necessary, with widespread investor adoption.

Transition to step 3: The (Un)intelligent Investor

Whereas equity’s value is independent of the markets belief because of its convertibility into assets and pro rata dividend share, money’s value is completely dependent on other investors.

Ben Graham, in his seminal piece on valuation, The Intelligent Investor, extolled the virtue of separating the price of an asset from Mr. Market. You can be a contrarian — in fact you have to be — and succeed in the equity markets because equity has recourse to cash flow. A low price relative to value represents a good buying opportunity. In the equity markets, if you invest in what everyone else believes to be true, the efficient market hypothesis will prevail. If you believe what the market believes, your return will equal the market’s and your LP capital will end up with Vanguard.

Unlike equities where you want to separate yourself from Mr. Market, with currencies you want to converge on what Mr. Market is telling you.

The more Mr. Market agrees with you, the more liquid and salable your currency is — that is, the more demand other people will have for your money.

Developer activity, buzz, dapp launches and ICOs are not leading indicators. Don’t follow the developers. Follow the money, and the developers will join.

Capiche?

When you are trading your time for money — also known as working in common parlance — you are betting that money will give you more optionality than your time / effort because other people will demand that money from you both now and in the future. Money, in this regard, is liquid time. Working for money is going long optionality. And holding that money vs getting rid of it today is betting that more people will demand that money in the future.

Unlike with equities, being an “intelligent” investor in money suffocates that optionality. You rarely benefit from being a contrarian when it comes to money. That’s why Bitcoin’s rise is teaching some bad lessons. If a stock doubles in price, ceteris paribus, it generally becomes less valuable because of the reduction in dividend yield. With money the opposite is true. BTC is orders of magnitude more useful today than when its price was $1 because it is more salable.

The market cap today is much higher, indicating more people accept and demand it

In money, you want to be an “Un-Intelligent Investor”. The best form of money will be the one that most people have accepted. The worst form of money, is the one that nobody demands to hold. Market cap is a representation of this dynamic.

The larger network a currency has, the better — which then causes more people to buy in, further reinforcing this value.As liquidity differences between two different moneys grow, there’s a disutility to holding whatever asset is less liquid. Holding a less liquid asset confers an opportunity cost and asset holders will seamlessly convert into the asset with highest optionality. As more people convert into the stronger asset, the differences between the two are exaggerated. Once other people recognize this, it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. The worse currency ultimately hyper-inflates and the other in relation to it hyper-deflates. Investors will be forced to converge on what the rest of the market is telling them, constantly recalculating and making internal predictions of what asset is most likely to do so.

On the free market there tends to only be one reserve currency because of these strong positive feedback loops of value.Step three is ultimately the process of all wealth converging into a single monetary asset. And the winner of that is determined by the long term holders dem.

Without long term holders, there’s no way to bootstrap a new currency and progress through the cycle above. No cryptocurrency market would exist without them. And cryptocurrencies would have zero chance of taking down any reigning monetary SoV’s without investors continued intransigence and unrelenting will to hold.

Investor obliviousness is a wrench in the gears of the regression theorem. But he who exits last from the old monetary asset will end up hanging their private keys on the wall like Zimbabwe dollars. Fear of missing out turns into fear of getting out.

Investors Control and “Incentivize” the Cryptocurrency Development

As we just saw, the market cap and valuation of any money is dependent on how much wealth is held in it. Per the cryptocurrency regression theorem, investing in a cryptocurrency is ultimately a bet on other people demanding to hold the asset in the future. For any cryptocurrency to win — for any of us to make money — we need to appease the long term investors. The money with the most intransigent and largest holder base will win.

Developers could try to launch an objectively better currency, but that doesn’t necessarily mean it will overtake the inferior one. To do so, investors need to follow. The only way developers get paid from a cryptocurrency is if they create something investors want to hold.

Good developers are invaluable. But in this regard, they’re like pilot fish who follow sharks around feeding off their spoils. Developers (and miners too) are forced into working on whatever investors are signaling they desire (segwit2x showed this too). The value of the tokens that they receive as their compensation is based on investor demand for it. Developers are ultimately dependent on investors (there’s some nuance here — yes BTC needs lightning network, for example).

Don’t mistake this as an assertion that developers are not important. I’d give up my first born to be Greg Maxwell or Elizabeth Stark. My broader point is that there is a feedback loop that exists which is catalyzed by investor interest. Investors signal that Bitcoin is the most likely to win through it holding the most wealth. The top developers work on it and buy bitcoin to capitalize on its rise. More investors join because of the strong technical roadmap. Victory.

But developers, are only incentivized — compensated — from a cryptocurrency if investors value it highly. Developers cannot create value in a vacuum with a crypto-asset. They need to create something that investors demand to hold. And ultimately, because of the crypto-regression theorem, a high initial valuation — which usually determines a significant portion of the dev pay — will be predicated on a high long term valuation.

Developer Incentives

Back to Naval’s initial assertion, the only reason utility tokens currently “incentivize” devs is because fly-by-night speculators and investors are holding tokens mistakenly, as I alluded to above. Developers are capitalizing off of investor uncertainty and the attendant overvaluations.

Bitcoin developer compensation hasn’t been nearly as explicit as with ICOs — but that doesn’t mean that it doesn’t exist. Unfortunately for many traditionalists many things often tend to work better in practice than in theory. Bitcoin Core is one of the most active open source repositories to ever exist. If that’s from ignoring incentives, it sounds like we need to banish so-called incentives from all open source projects.

What’s relatively unique to bitcoin is that because a salary or pre-sale allocation isn’t granted to developers, many of them are forced holders if they want to capitalize on their development work. Given long term holders are pivotal to a cryptocurrency’s success, there could be no better synergy than having the holder base and developer base overlap. And this is the most common form of developer incentive in bitcoin. Rather than ignoring developer incentives, bitcoin almost elegantly forces their alignment. Developers only get paid if they appease the investors through token appreciation — and often times they are the largest investors. It’s forced skin in the game.

This next point may hurt the most to those aforementioned SV-ethos infected investors. But it frankly may be the case that this “tech revolution” can succeed without the help of VC investors disrupting crypto-incumbents. As exciting as it is to take down Goliath, sometimes it can be more beneficial to have him on your side. And the notion that you can take down Bitcoin through a large pre-mine allocation to developers is like trying to fight Apple by poaching its engineers with monopoly money.

I think it’s unfortunately the case that most developers cannot and should not be contributing to cryptocurrencies at the protocol level because they don’t have the requisite knowledge. And that’s fine. There are lots of other problems in the world for developers to work on and VCs to fund. It’s not necessarily a good thing that ICO funding is outpacing traditional, non crypto equity financing. Most of that capital could also be re-allocated to supporting the best crypto-money that exists.

Developers follow the investors. And so long as investors continue to value ICOs, developers will launch them. When this inevitably changes, so will the “developer incentives”. The sooner investors complete altcoin rehab, the better we can correctly incentivize developers.

Conclusion

Investors are the most important piece of the puzzle. Investors aren’t free riding, they are (1) signaling to the market which currency they desire and (2) compensating devs and other holders for their work.

Devs and early VCs should be gracious to investors, for that is how they get paid.

Valuation is predicated on investor behavior and so is developer compensation. Devs ultimately follow the holders in terms of valuation. Investors are the most important aspect

Holders control the protocol.

Disclaimer: The comments, views, opinions and any forecasts of future events reflect the opinion of the quoted author or speaker, do not necessarily reflect the views of Tetras Capital Partners, LLC (“Tetras”) or other professionals at Tetras, are not guarantees of future events, returns or results and are not intended to provide financial planning or investment advice.

Visions of Bitcoin

How major Bitcoin narratives changed over time

By Nic Carter & Hasu

Posted July 29, 2018

Do I contradict myself? Very well then, I contradict myself I am large, I contain multitudes.

– Walt Whitman, Song of Myself

Perhaps the most enduring source of conflict within the Bitcoin community derives from incompatible visions of what Bitcoin is and should become. Businesses building on Bitcoin, believing it a cheap global payments network, eventually became nonviable when blocks filled up in 2017. They weren’t necessarily wrong, they just had a vision of the world that ended up being a minority view within the Bitcoin community, and was ultimately not expressed by the protocol on their desired timeline.

In the absence of a recognized sole leader, Bitcoiners refer to founding documents and early forum posts to attempt to decipher what Satoshi truly wanted for the currency. This is not unlike US Supreme Court justices poring over the Constitution and applying its ancient wisdom to contemporary cases. Others reject textual exegesis and focus instead on a pragmatic analysis in context.

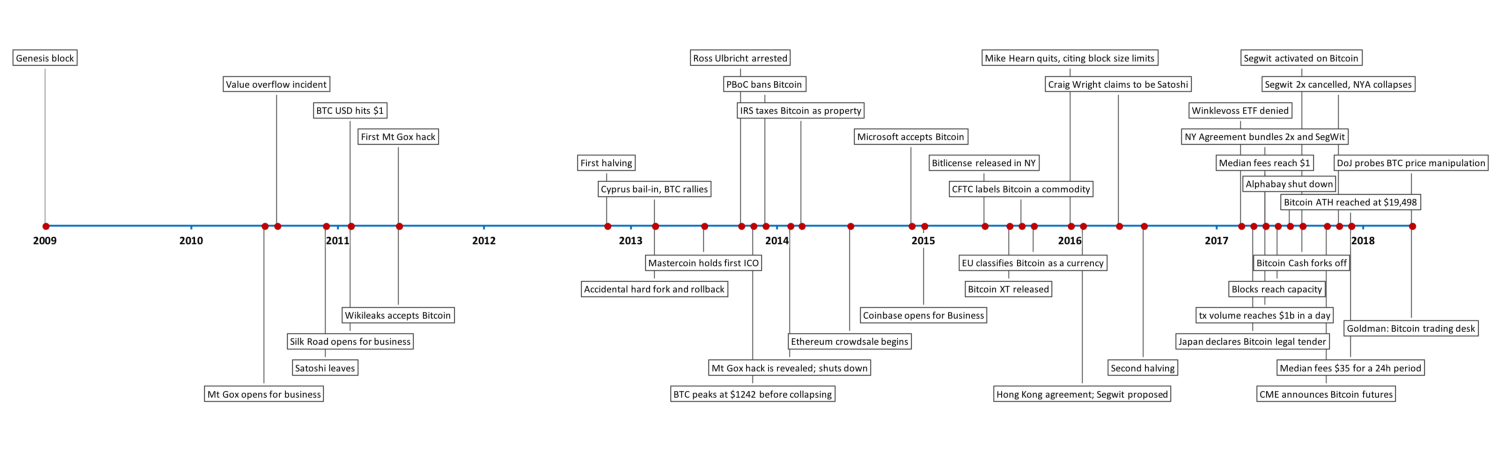

Conflicts within Bitcoin thus arise from entities who hold visions of the protocol that are mutually exclusive — and this leads to friction when these visions cannot be reconciled. Visions of Bitcoin are not static. Technological developments, practical realities and real-world events have shaped collective views. This post is an attempt to aggregate the various dominant narratives that have characterized Bitcoin throughout its 9-year history. This post builds on excellent prior work by Murad Mahmudov and Adam Taché, and we suggest you add that to your reading list.

Changing narratives

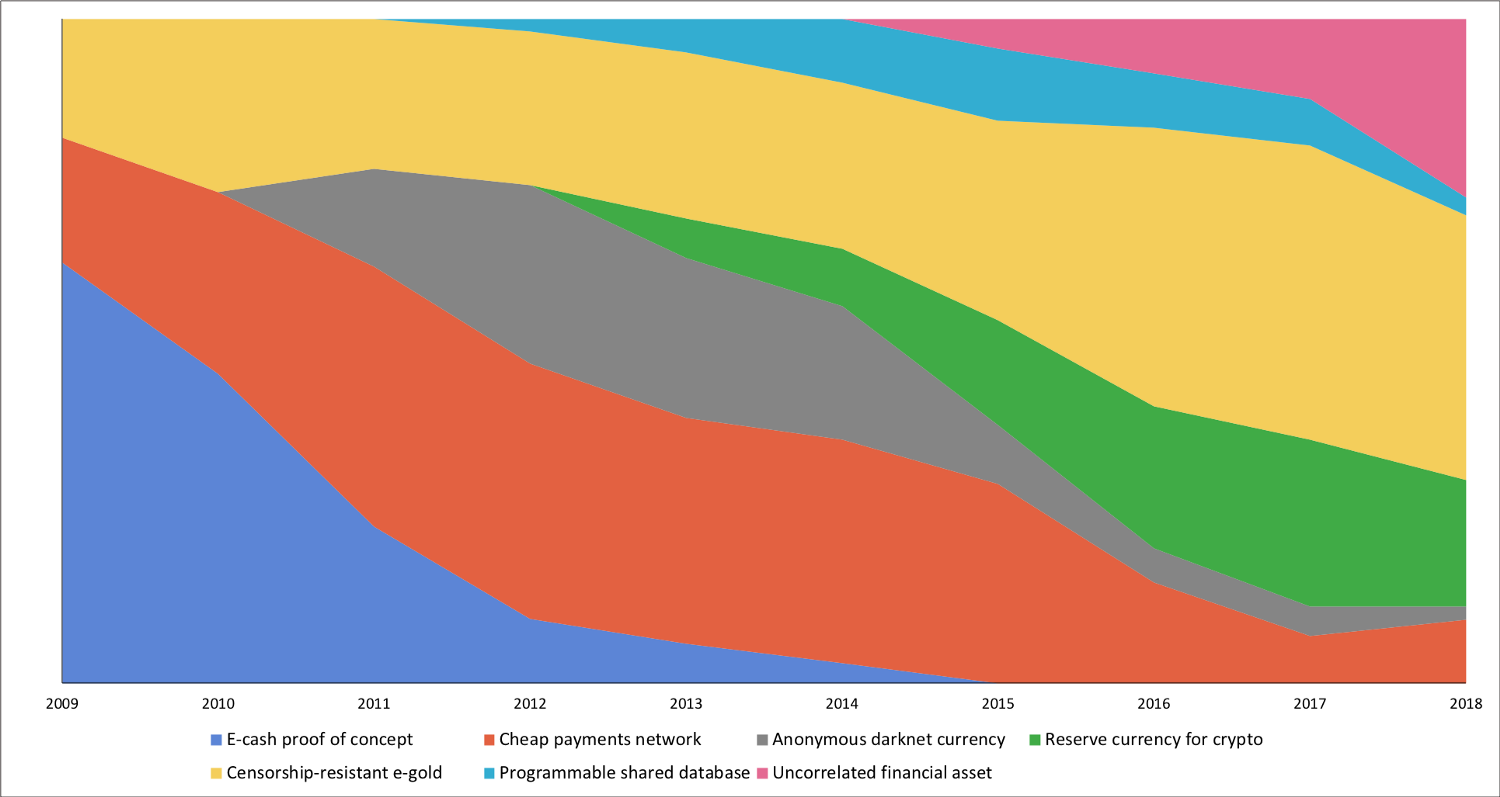

Here, we want to more granularly explore the prevalence of key narratives. We identify seven distinct major themes that have held positions of prominence among Bitcoiners throughout its history. Note that these do not necessarily have to be the most influential narratives — we are instead focusing on major strains of thought that have characterized Bitcoin users.

In rough order of appearance, these are:

- E-cash proof of concept: the first major narrative, this was the general view of Bitcoin in its earliest days. Back then, cypherpunks and cryptographers were still appraising the nascent project and determining whether it worked, if at all. Since all prior e-cash schemes had failed, it took a while for people to be convinced of its technical and economic viability and move on to more expansive conceptions of the protocol.

- Cheap p2p payments network: an extremely popular and pervasive narrative. Some believe this is what Satoshi had in mind — a straightforward currency for peer to peer internet transactions. A decentralized Paypal or Venmo, if you will. Since microtransactions are a key component of internet commerce, proponents of this view generally believe that low fees and convenience are an essential characteristic of such a currency.

- Censorship-resistant digital gold: the counterpoint to the p2p payments narrative, this is the view that Bitcoin primarily represents an untamperable, uninflatable, largely unseizable, intergenerational wealth store which cannot be interfered with by banks or the State. Proponents of this view de-emphasize Bitcoin’s use for everyday transactions, arguing that security, predictability, and conservatism in development are more important. We’re callously lumping in sound money believers into this camp.

- Private and anonymous darknet currency: the view that Bitcoin is useful for anonymous online transactions, in particular to facilitate black market online commerce. This is not necessarily mutually exclusive with the e-gold position, as many proponents of the digital gold view believe that fungibility and privacy are important attributes. This was a popular narrative before the chain analysis companies had success de-anonymizing Bitcoin users.

- Reserve currency for the cryptocurrency industry: this is the view that Bitcoin serves an essential purpose as the native currency for the cryptocurrency/cryptoasset industry more generally. This is a view espoused by traders for whom BTC is the numeraire — the currency in which the prices of other assets are quoted. Additionally, traders, businesses, and distributed networks that hold reserves in BTC de-facto endorse this view.

- Programmable shared database: this is a slightly more niche view, and generally involves the understanding that Bitcoin can embed arbitrary data, not just currency transactions. Individuals holding this view tend to see Bitcoin as a programmable, expressive protocol, which can facilitate broader use-cases. In 2015–16, it was popular to express the notion that Bitcoin would eventually absorb a diverse set of functionalities through sidechains. Projects like Namecoin, Blockstack, DeOS, Rootstock, and some of the timestamping services rely on this view of the protocol.

- Uncorrelated financial asset: this is a view of Bitcoin that treats it strictly like a financial asset and finds its most important feature to be its return distribution. In particular, its tendency to have a low or nonexistent correlation to all manner of indexes, currencies, or commodities makes it an attractive portfolio diversifier. Proponents of the view are generally not too concerned about owning spot Bitcoin; they are interested in exposure to the asset. Put another way, they want to buy Bitcoin-flavored risk, not necessarily Bitcoin itself. As Bitcoin has become more financialized, this conception has gained steam.

In the chart below, we’ve weighted these various narratives according to their popularity at the time.

This isn’t modern art — it’s our representation of Bitcoin’s changing tides

This isn’t modern art — it’s our representation of Bitcoin’s changing tides

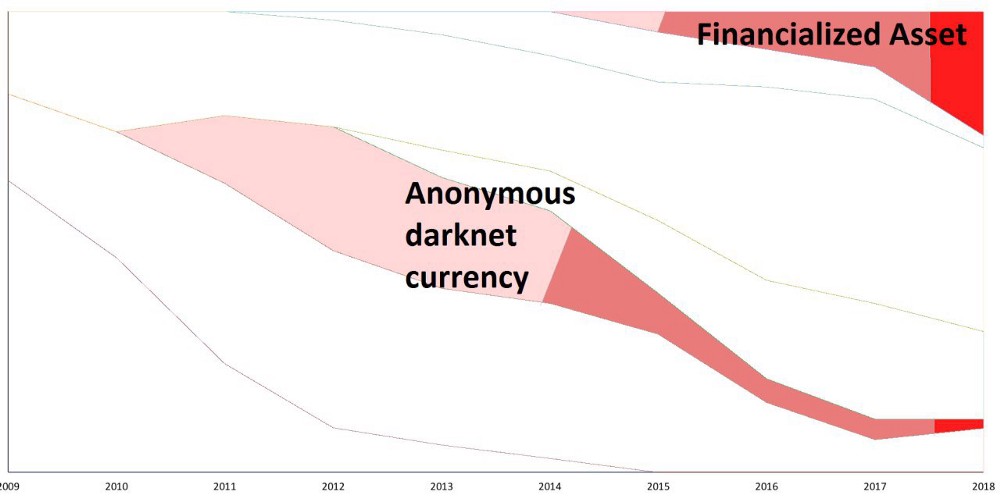

In this chart, we lay out the relative influence of the seven narratives we identified above. As you can see, the e-cash proof of concept was the dominant view at the start, although the p2p payments network and digital gold views were also espoused at the time. Later, Bitcoin as an anonymous darknet currency gained steam with the Silk Road. The idea never really died off, and Bitcoin is still used on the darknet today, even though other privacy-oriented alternatives exist.

As ICOs were invented and a broader market of altcoins began to proliferate, BTC became the reserve asset for that larger economy. This grew to become a significant feature of Bitcoin, especially in the bull markets of 2014 and 2017. We note that the p2p payments contingent remained influential until mid 2017, when they largely migrated to Bitcoin Cash (some had already left for Litecoin and Dash). However, with the emergence of Lightning in 2018, there has been an upswing of enthusiasm for online microtransactions and fee-less internet payments.

In 2015 and 2016, sidechains became a popular talking point, and it was assumed that Bitcoin would soon boast a much-expanded functionality, obsoleting most altcoins. Related functionality-extending projects like Mastercoin (now Omni), colored coins, Namecoin, Rootstock, Blockstack, and Open Timestamps, contributed to this general view. However, as sidechains proved complicated to implement, non-money uses of Bitcoin fell out of favor.

As Bitcoin emerged from the 2014–15 bear market, analysts began to contemplate its status as a differentiated commodity-money. In November 2015, Tuur Demeester published an investment note entitled “How to Position for the Rally in Bitcoin,” arguing that it had unique characteristics as a portfolio asset. In mid-2016, Burniske and White influentially argued that Bitcoin represented an entirely new asset class. These analysts noticed Bitcoin’s stubbornly low correlations with traditional assets, and as this persisted, Bitcoin as a portfolio diversifier gained steam among certain forward-looking corners of the asset management industry. Today this is a popular view, driving much of the demand for financial products which would give traditional investors exposure to Bitcoin.

Throughout all these regimes, the digital gold conception has remained influential, and now is the consensus view, predominating over the p2p petty cash faction, which largely departed with Bitcoin Cash. Today, after years of strife and infighting, this is the majority view. However, not all Bitcoin users are ideological bitcoiners, and wanted to reflect this in the chart. Many Bitcoin holders hold it as a portfolio diversifier, some still use it for anonymous darknet transactions, and the p2p cash contingent has re-emerged alongside Lightning.

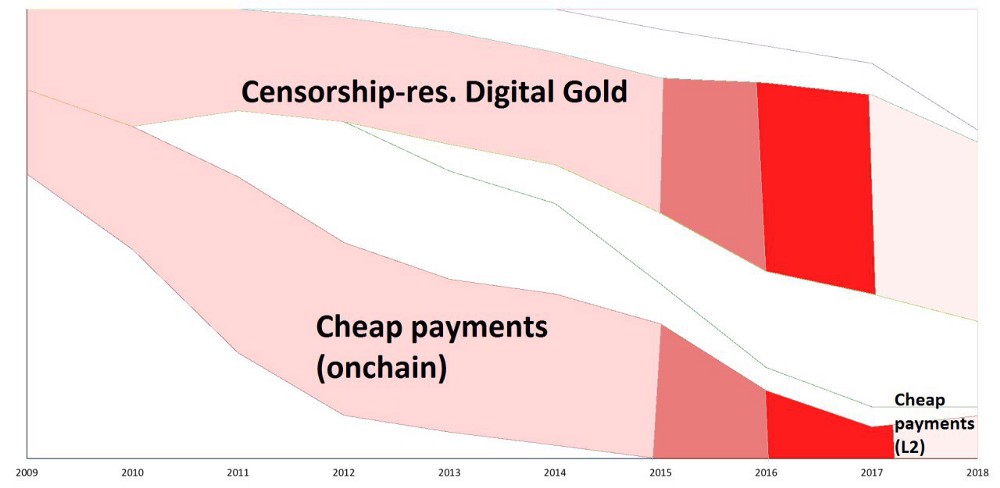

Tension and release

If you scrutinize the above chart, you’ll notice that some of the visions of Bitcoin are entirely incompatible. For instance, a move to a global on-chain payments network conflicts with the digital gold view, as emphasized by Spencer Bogart. We’ve depicted the conflict between these views of the world by isolating them on this chart.

The conflict really began to be fought seriously with the release of BitcoinXT in 2015, although rancorous discussions had long preceded that. Further provocations including Bitcoin Classic, Unlimited intensified the conflict. It reached its peak in mid 2017 when Bitcoin Cash finally forked. During the bull run of late 2017, Bitcoin fees reached extreme levels, leading to defections to the Bitcoin Cash camp. However, since then, fees have settled down and the need for big blocks appears less urgent.