Bitcoin’s Resilience to Exponential Change

| If you find WORDS helpful, Bitcoin donations are unnecessary but appreciated. Our goal is to spread and preserve Bitcoin writings for future generations. Read more. | Make a Donation |

Bitcoin’s Resilience to Exponential Change

By Yassine Elmandjra & Dhruv Bansal on Unchained Capital Blog

Posted May 15, 2020

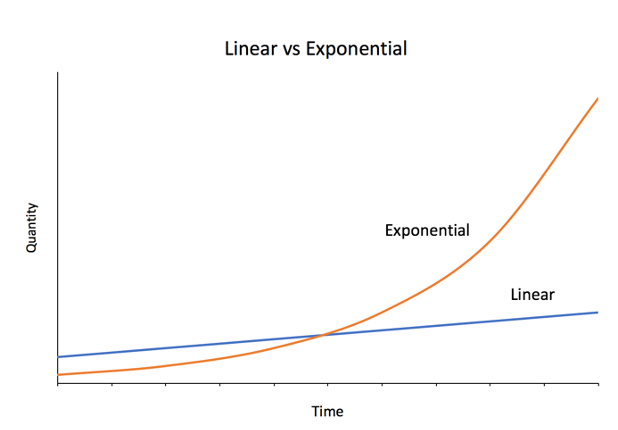

Exponential growth is often grossly underestimated. In technological innovation, exponential trends are masked as linear ones, giving old technologies a false sense of comfort. As a new technology gains momentum, forecasts based on linear thinking turn out to be misleading.

In this world, it becomes hard to predict the winners. As innovation proliferates, old technologies are rapidly displaced by new ones. Competitive market dynamics create little competitive advantage and leave no company or industry immune to disruption. Countless examples show that disruption is often initiated from outside the established market leaders. IBM dismissed the threat of personal computers, allowing competitors to capture the market years before it entered. Digital wallets are disrupting legacy banking. Electric vehicle manufacturers are overtaking the transportation industry.

While new entrants begin dominating a new paradigm, traditional incumbents remain over-committed to a particular conception of a technology. This over-commitment controls decision making processes. When an innovation appears, established industries tend to double down on their allegiance to traditional technologies that once made them market leaders. Falling into a sunk cost fallacy, these leaders prohibit themselves from employing a “rip and replace” strategy. It becomes only a matter of time before they submit to new innovation and survive, or stagnate and die.

Incumbents who are successful in keeping up with technological innovation create products and compelling narratives about the role these technologies will have in society. Once accepted into the market, these technologies rely on incumbents to maintain their relevance. If not, the “cheaper, better, faster” solution replaces both the technology and the incumbent.

Herein lies the implication of traditional market technologies: in an exponentially growing world, central planners are necessary for their survival. If a technology is to remain relevant, effective central planning is required by the entities adopting that technology. Absent an effective central planner, technologies may fall victim to disruption caused by exponential growth.

But what happens when technologies with _no _central planner, like Bitcoin, are exposed to exponential change? How might decentralized systems adapt? Or are their fates doomed by exponential rates of technological advancement?

Bitcoin’s exposure to exponential growth

Once dominated by hobbyists drawing CPU from desktops, mining bitcoin has evolved into a hyper-competitive, multibillion-dollar industry harnessing specialized chip hardware. Through exponential advancements in hardware, mining today is exclusively powered by application specific integrated circuits (ASICs), hardware designed for the sole purpose of mining Bitcoin.

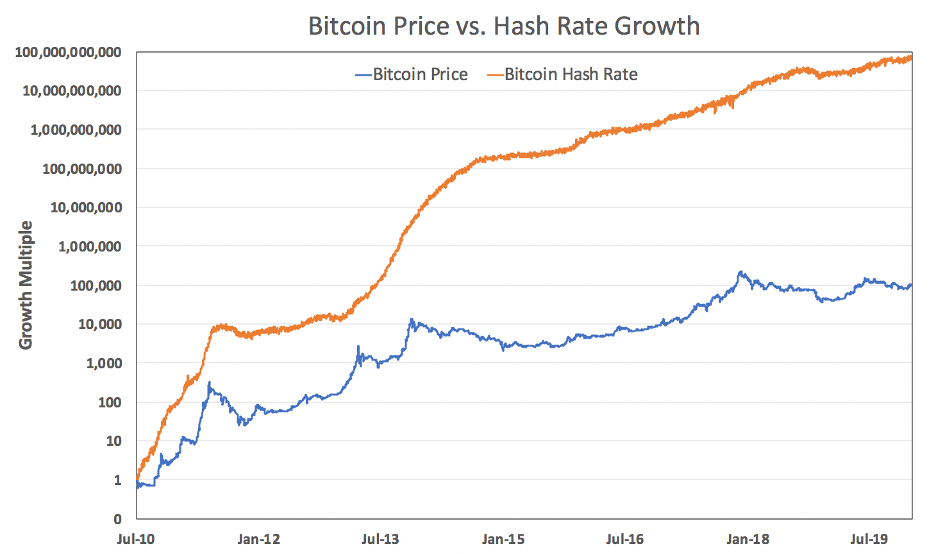

As a result of exponential advancements in hardware and an increased demand to mine, the number of computations dedicated to mining Bitcoin has grown by nearly 11 orders of magnitude, a 1 million times faster rate than Bitcoin’s increase in price.

Despite these exponential advancements, Bitcoin’s fundamentals remain intact. Specifically, Bitcoin has been able to issue new coins and produce blocks at a constant rate of production, ensuring a predictable monetary policy.

So how does Bitcoin achieve immunity from this exponential growth?

Proof-of-work helps Bitcoin achieve immunity

Bitcoin’s resistance to exponential change is best explained by unpacking creator of Bitcoin Satoshi Nakamoto’s implementation of proof-of-work.

As suggested in its name, proof-of-work was initially conceived as a way to make certain things harder to create. Spam, denial of service, and other attacks all rely upon an attacker’s ability to flood a network with useless traffic at low or no cost to the attacker but at great cost to the network.

In a centrally planned network such as a subway system (or a corporate LAN), a central planner can issue tickets to grant users access, mediate traffic flow, and establish checkpoints to validate these tickets. As a network exponentially grows, it becomes increasingly expensive for a planner to maintain checks and balances. Attackers who obtain a ticket machine (or some private key) can flood the network with valid traffic without paying for the ticket.

Bitcoin’s implementation of proof-of-work embeds a system of checks and balances by creating a digital, self-validating ticket that is measurably difficult to produce. Proof-of-work tickets can’t be printed out on a stolen ticket machine because no machine exists that can cheaply make proof-of-work tickets. The only way to produce a ticket is to do work, and anyone who sees the ticket will be able to verify exactly how much work went into producing the ticket.

If transmitting an email or web request required first performing proof-of-work, the rest of the network could easily identify how much work went into messages before they decided to process them. A market-driven computing price would emerge that would be trivial for users to verify and difficult for attackers to exploit. As the network scales, attacks would become more expensive and less common.

A promotion offering subway riders the chance to exercise briefly instead of paying for a ticket. This is a funny example but it’s not proof-of-work; possessing the ticket isn’t proof you did the exercises. Even a video of you doing the exercises isn’t proof as it might be faked. Real proofs-of-work are believed to be unfakeable. (https://edition.cnn.com/2013/11/15/tech/apparently-this-matters-squats-moscow-subway/index.html)

Proof of work is time

However, making it difficult to mint coins is only one part of creating a distributed currency. Absent a central planner, the various “minters” would also need a ledger to list and record trades of the coins they were creating. This is solved by having every market participant keep its own copy of the ledger and update it whenever it was made aware of any new transfer of tokens. But what happens if some participants receive conflicting transactions in different orders?

Enter the double-spend problem.

The double-spend problem is solved by answering “which transaction is first?” In other words, all market participants must agree on the order of events. Satoshi’s solution was to implement an ordered sequence of “blocks” each irrevocably cemented to its ancestors using proof-of-work. Combined with the “heaviest chain” rule, this “blockchain” would provide a universal order to all (sufficiently confirmed) transactions.

Even if the integrity of the order of transactions could be guaranteed, however, the rate of block production would be difficult to regulate given changes in the amount of work performed. In Bitcoin’s case, an irregular block production would mean irregularity in issuing bitcoin. Irregularity in issuing bitcoin would mean an unpredictable monetary policy. How could blocks be produced at a constant rate if the amount of work performed to produce blocks was constantly changing?

Bitcoin’s difficulty rebalancing algorithm

Satoshi realized that proof-of-work could also be used to engineer a distributed market-driven clock. The clock would provide both an ordering to events and tell time by producing new blocks. But in order to keep itself calibrated, the clock would need a ticker that would readjust based on the amount of work performed to produce blocks. This is known as the difficulty rebalancing algorithm.

Bitcoin’s difficulty rebalancing algorithm is Bitcoin’s elegant way of providing this calibration mechanism. The importance of Bitcoin’s difficulty rebalancing algorithm is underappreciated and highlights how proof-of-work is used to resist exponential change. The goal of difficulty rebalancing is to ensure that a certain number of blocks (2016) always gets mined in the same real-world time period (2 weeks). Shared time in centrally planned systems is typically “looked up” by asking a central time-keeping server. Bitcoin has no time-keeping server, and instead resorts to this form of crowdsourcing.

During a rebalancing, the Bitcoin software examines submitted timestamps included in each of the prior 2016 blocks. A validation rule is built into the software that ensures valid blocks have timestamps within a small range of each user’s own configured time. The block timestamp is thus used as a “crowdsourced timestamp” for the network. During rebalancing, the software uses prior blocks as a sample (N=2016) from which to statistically estimate the amount of time those blocks took to produce. Through this mechanism, Bitcoin’s difficulty readjustment is able to account for any changes in work and act as a subversion when exponential growth in work is performed.

Regardless of changes in work, the clock serves to measure consistent durations of time. If blocks are produced at a (statistically) constant rate, an issuance schedule can be encoded into block production, establishing a fixed monetary policy. This solves a potential “supply glut” by ensuring that difficulty follows work in such a way that block production remains constant.

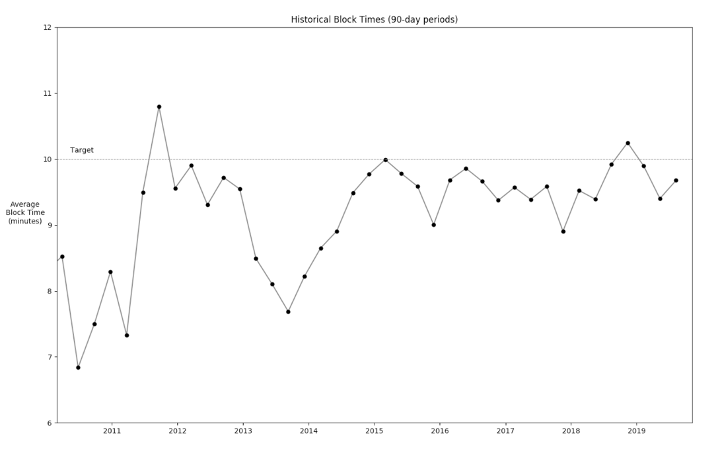

How well does Bitcoin’s clock work? As shown in the graph below, for more than a decade, Bitcoin has maintained a consistent block time despite exponential increases in work performed, also known as hashrate. Over time, block times have moved closer to the target block time of 10 minutes, suggesting that Bitcoin becomes a more accurate clock as it scales.

Bitcoin turns threat into virtue

Decentralized systems can survive (and even thrive) in the absence of a central planner if they are designed to be resistant to exponential advancements in technology. It is with this implicit realization that Satoshi Nakamoto, the anonymous creator of Bitcoin, pursued creating a distributed, market-driven digital money immune to disruption in an exponentially growing world.

Centrally planned systems are easier to design, construct, and reason about than distributed, market-driven systems. However, the system itself cannot survive without central planners managing adoption and participation. Central planners regulate, coordinate, coerce, and monitor the participants and activity in the system.

In distributed systems, participants can come and go as they please. They can choose to break rules and be adversarial instead of cooperative. They can attempt to subvert, divide, or destroy each other, or the market itself. With the right incentives, however, decentralized systems can sustainably coordinate activity at a larger scale more efficiently, robustly, transparently, and fairly than centrally planned systems.

By implementing proof-of-work, Bitcoin has become the first successful digital money immune to the exponential disruption vector. Proof-of-work in Bitcoin is used to throttle miners, mint new tokens, order transactions, and crowdsource time measurements. With cumulative proof-of-work as a proxy for Bitcoin’s security, exponential growth in computing technology has seemingly turned from a potential threat into a virtue. Bitcoin neatly steps around exponential advancements in technology by ensuring a counter-balancing growth of difficulty, suppressing the influence of exponential change on the network and instead elegantly using it to further protect itself.

Thanks to colleagues at ARK Invest and Phil Geiger for reviewing and providing valuable feedback.