Bitcoin and The Business Cycle

| If you find WORDS helpful, Bitcoin donations are unnecessary but appreciated. Our goal is to spread and preserve Bitcoin writings for future generations. Read more. | Make a Donation |

Bitcoin and The Business Cycle

By Ben Kaufman

Posted April 16, 2020

For centuries, production in capitalist countries seems to progress in some kind of “cycles”. Every few years, the economy experiences a period of sharp economic growth which is then upset by a collapse of businesses and a high unemployment rate — a recession. This cyclical movement of the market, repeatedly going from an economic boom to bust, is known as the “business cycle”. Social scientists of multiple disciplines have suggested numerous explanations for this phenomenon, from “under-consumption” to some psychological propensity. Yet, so far, no popular counter-measure pursued has solved this problem. Central banks have evidently failed to “cure” this alleged “market failure”, and despite the enormous, continuous growth in their power and influence, we once again seem to be at the beginning of a devastating recession.

Despite the confidence on the side of central bankers in their ability to handle this issue, it seems that, especially since the last crisis of 2008, the public is losing patience with the current system. People are getting fed up with footing the bill for the mistakes of the financial system, and very justly so. The scheme at work is already clear and visible. The economists grievously fail, and the taxpayer pays the costs (and their salaries)¹. It’s obvious that this system cannot continue. Yet, the right alternative — the solution — is still far from obvious. Nevertheless, the mainstream and most academia appear to agree on one thing, that money must be managed by the government, that is, through central planning.

They tend to look at the economy as a machine — some kind of a black box which is running on an engine fuelled by money. The more “fuel” you throw in, the quicker the engine will go, and the faster the economy will move. While the different economic schools and doctrines usually provide different theories and explanations, their practical controversies and disagreement are primarily around at what point injecting more “fuel” would cause the “machine” to run too fast, overheat and eventually blow up. That is, how much money would be too much for the economy and lead to problems or even to hyperinflation. Regardless of the many differences between the popular doctrines, the issue of money is where you will find their most enthusiastic agreement. The money supply² must always increase! Printing, bank credit expansion, “liquidity injection”, “quantitative easing”, public deficit spending, even outright handouts — just throw it out of a helicopter if that’s what it takes — but you must never let the inflow of money slow down!³

This approach of monetary “engineering” is undoubtedly the most popular, and has guided policies for more than a century. But, considering its failure to deliver on any of its promises⁴, there seems to be a good reason for questioning this approach. In fact, if there is anything to learn from the last hundred years, it is that government control over money, namely central banking, doesn’t promote prosperity. Expanding money and credit does not cure the problem of the business cycle (or any other issues for that matter) — this approach has failed every time. The common analogy that the economy is like a machine operated by the state fueling it with money might sound sensible to some, but does it really fit? Is the theory we have learned to accept, quite by default, actually correct?

In this article, I will present the “heterodox” approach of the “Austrian school” of economics. The Austrian school approaches the questions of economics from the view of individual actions and incentives, looking at the economy as an “organic” complex resulting from the many actions of individuals. Its theory of the business cycle is probably one of its central, though most controversial, achievements. The purpose of this article, however, is not merely to explain the Austrian Business Cycle Theory (ABCT), and certainly not to justify its validity. Many other books already provide such brilliant expositions⁵. The goal of this article is to discuss the possibility of economic reform which builds upon the theoretical works of the Austrian school. My aim here is to lay down the argument for how Bitcoin could be the key to preventing the business cycle — enabling greater and more sustainable economic growth.

Economic Growth

So to begin our discussion, we shall first look at how a healthy economy grows. Adam Smith, the “father of economics,” has attributed economic growth chiefly to the division of labor, that is, to the specialization of individuals in performing specific tasks. However, there is a much more critical aspect of human progress which Smith overlooked. As Carl Menger, the founder of the Austrian school of economics explained, it is the availability of “factors of production,” that is capital, on which economic growth is dependent, and which also sets the limits for the division of labor.⁶

Capital, or capital goods, are the goods which are not used for direct consumption, but are used in the process of producing other goods, eventually reaching to consumers as “consumption goods.” Menger has explained this difference by referring to different “orders” of goods. The goods which consumers directly use, like food, clothes, and cars, are the goods of the “lowest, first order.” If we take bread, for instance, then we could say that flour is a “second-order” good in the process of producing it. Wheat can then be called a third-order good, and the land on which the wheat grew upon a fourth-order good. The order of a good is nothing inherent in it, but is rather “a product of reasoning” based on how a person intends to use it. Therefore, the same good can be of different orders when employed at different stages of production. The point here is, of course, not the assignment of the specific orders of goods, but understanding that production is a structure with varying “depth”. Furthermore, as we will now see, the higher the orders of goods we use in a production process get, that is, the “deeper” our production structure is, the more we will be able to produce.

As an example, consider a lumberjack cutting wood with an ax, as compared to another one which uses an electrical chainsaw. Clearly, the latter will be much more productive at his work, as the capital good he employs is much superior to the one used by the former lumberjack. But, it is no less clear that the chainsaw requires the employment of much higher order goods to assemble, its production process is longer and more complex. While an ax could be produced even by primitive people, from quite simple raw materials, the chainsaw requires the use of industrial equipment, like an engine and a power source, which by themselves require the use of many other goods, and so on. In other words, the chainsaw necessitates the accumulation of much (much) more capital and the use of much higher orders of goods to produce — it needs a “deeper” production structure.

Menger’s student, economist Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk, has termed this property of increasing length and complexity of production, the “roundaboutness” of production processes. The more “roundabout” a production process is, the more and higher-order capital goods it means are employed. His choice of the term “roundabout” attempts to signify a crucial concept. To produce more and better consumer goods, we must first take the time to create more capital goods. By “deviating” from the straight line we wish to follow to get to our main goal of producing the final consumption goods (like firewood), taking the additional effort and going first to produce something else (the capital needed, like the ax or chainsaw), we can manufacture much better, or a greater quantity of, final products. The process of human progress, of improving welfare and material conditions of people, could most adequately be described as the process of capital accumulation. Our development and economic growth is dependent on and limited by the availability of capital goods for production. Thus, to understand the actual process of economic growth, the next step to look at is how capital accumulation works.

Accumulating capital means increasing the level of savings that a person holds. It means withholding consumption of goods and, instead, saving them and employing them in further production. When considering an individual working alone, like a fisherman building himself a fishing rod, the process of capital accumulation is quite straightforward. The fisherman delays his “production” of fish in the present and instead takes the time to build a fishing rod. He will need to postpone his consumption of fish while producing the rod but will later be able to use it to catch many more fish. Eventually, he will have more capital savings (the rod) and will be able to produce (fish) more efficiently. However, when discussed in the framework of the market economy, the process suddenly becomes much more “abstract” and harder to follow. Therefore, it is of the utmost importance to understand the specifics of capital accumulation in the market economy.

The market economy is a system of the division of labor. It is a “framework” in which private individuals own capital, exchange goods and services, and cooperate to achieve their ends. Its most important property is the existence of a pricing system for all traded products and services, denominated in a common medium of exchange — money. Therefore, the allocation of capital in the market economy is done mostly by using the money prices of goods.

Most people tend to confuse money and money prices. When we say, for instance, that our lumberjack saved 100$ by producing firewood, what we mean is that he created something priced on the market as worth 100$. If he decided to use the firewood for consumption, he may do so either directly — for example by using it to make fire, or indirectly, by selling it for 100$ of cash, spending that on something he will actually consume. If, however, he prefers to increase his savings, he could refrain from consuming the wood, storing it for later, or using it to make new work tools (capital). Or again, as the usual course of the market economy goes, he could sell it for cash, and either save that money to spend later, spend it now on buying more capital goods to use, or lend it to or invest it in some enterprise. The more capital goods people accumulate, either directly by owning them, or indirectly, through money savings, lending, and investing, the more will the economy progress.⁷

As we now see, the most important force of economic growth is saving and accumulating capital, which requires deferring consumption of the goods produced. Therefore, we now face a new question. How long will a man be willing to defer his consumption in order first to accumulate more capital? In other words, how does a man, and eventually the economy as a whole, decide the length of production? That is, whether to focus on short term production of relatively fewer consumer goods sooner, or longer-term production, employing more “roundabout” processes to produce more (or better) consumption goods later.

The answer is that people decide according to their time preference. It is a generally accepted⁸ that all else being equal, a person will always prefer to satisfy his needs sooner rather than later (as for every person time is finite and the future is uncertain). This means that, for people to defer their present consumption, the future output expected from taking longer (more roundabout) production efforts must be high enough to compensate for this delay in consumption. Put simply, people value time, they prefer to attain their ends sooner rather than later, and the extent to which they value the present more than the future is their level of time preference.

Having high time preference, a person will be less willing to defer his consumption, and will be more present-oriented in his economic activity. In contrast, a person with lower time preference will prefer to wait longer and take more roundabout processes, as they will sufficiently compensate him for the increase in production length. We may say that the time preference of people is what regulates the length of production in the economy.

The lower time preference is, the more future-oriented people are, and the more capital they save and accumulate to enhance productivity and develop the economy.⁹

Again, in the case of an isolated economy of a single individual, there will not be much further question of how the process goes. In such a case, the same person does everything by himself. Just to clarify, retaking the example of a fisherman, if his time preference is relatively high, we will not be willing to defer his consumption to make the fishing rod first. However, if he has a low enough time preference, he will prefer this more “roundabout’’ process of making the fishing rod while catching no fish at first and then use it to increase his productivity. But as we said before, the process looks different when we introduce the division of labor of the market economy. In the market, production is directed according to consumers’ demand¹⁰, reflected through the price system.

Time is a factor of production. In fact, it is the only factor of production without which no production is possible. As such, time, that is, the time preference of the consumers, also has its money price in the market, namely, the interest rate. The interest rate is the price required to withhold capital from others for a certain time¹¹. As people save more, thus lower their time preference, it means that they are willing to delay their consumption for a lower “compensation”¹² compared to what they used to, and will accordingly offer their funds at a lower cost (interest rate).

As the interest rate gets lower, capital becomes cheaper for entrepreneurs to obtain. Projects which were previously too long or too capital intensive to be profitable suddenly become viable investments, as more capital is available at lower costs. Thus entrepreneurs will find it profitable to expand their businesses and open new initiatives, and consequently will expand and deepen the production structure by taking more roundabout production processes. What happens is that, by taking on more loans (or investments) from savers, entrepreneurs will be able to purchase the capital saved by the people who lowered their time preference (as lower time preference means more saving). This is how new capital accumulated gets into the production structure of the market economy, how resources are mobilized and the division of labor taking place. Prices serve as the guiding indicator for producers in the market economy, and the price of time, the interest rate, serves as an especially important indicator, as it is present in all imaginable processes of production and regulates their length and use of the available resources.

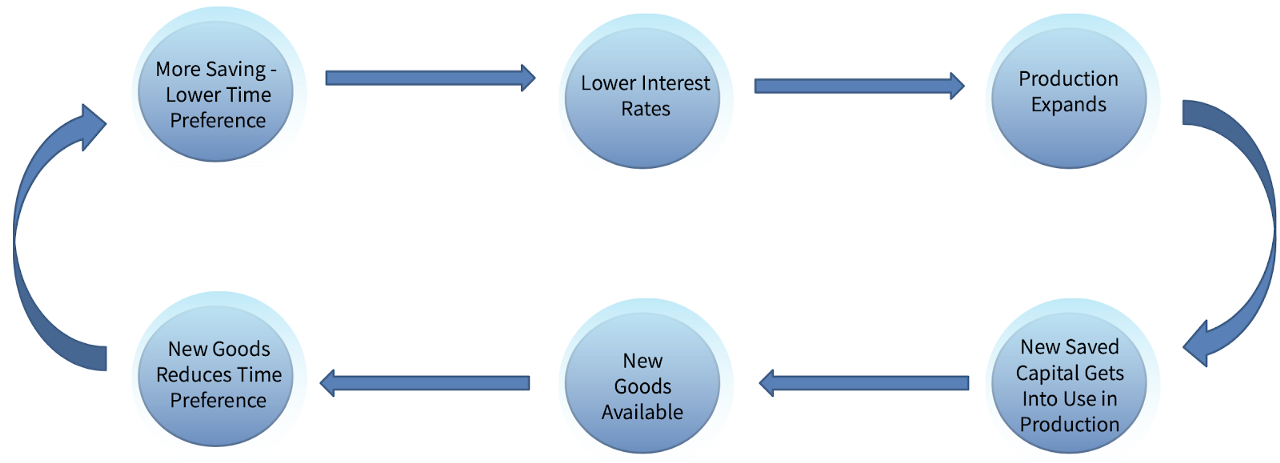

As these more roundabout processes of production mature, there will be a greater supply of goods (could be both capital and consumption goods) in the economy. People will then be able to lower their time preference and increase their savings without diminishing (or even while increasing) consumption. In a sense, there is a positive feedback loop, where lower time preference and longer-term view allows production to expand, eventually making more goods available, allowing to reduce time preference even further and so on. This is the process of civilization, by which humans have raised themselves from poverty and destitution to the modern prosperity, relative to past generations, that we have today.

The Business Cycle

So far, we have not seen any issue which should lead to the appearance of the business cycle — the recurring periods of great economic boom followed by a collapse of projects throughout the whole economy. So now we shall turn to our main problem here, what, indeed, is the cause of the business cycle?

According to the Austrian theory, developed initially by Böhm-Bawerk’s student, economist Ludwig von Mises, the root of the problem is to be found in the intervention of governments and central banks with the money supply, more accurately, with their efforts to increase the money supply and expand credit.¹³ In simple terms, what credit expansion means here is the creation of money, out of thin air.¹⁴ There are many ways today by which governments aim to expand credit, like Quantitative Easing, fractional reserve banking¹⁵ — which is insured by the taxpayer (implicitly or explicitly) and fully regulated by the state, and various other accounting schemes and financial “tools.” Still, the essence of all those schemes is to increase the supply of money and credit in the economy, essentially out of thin air.

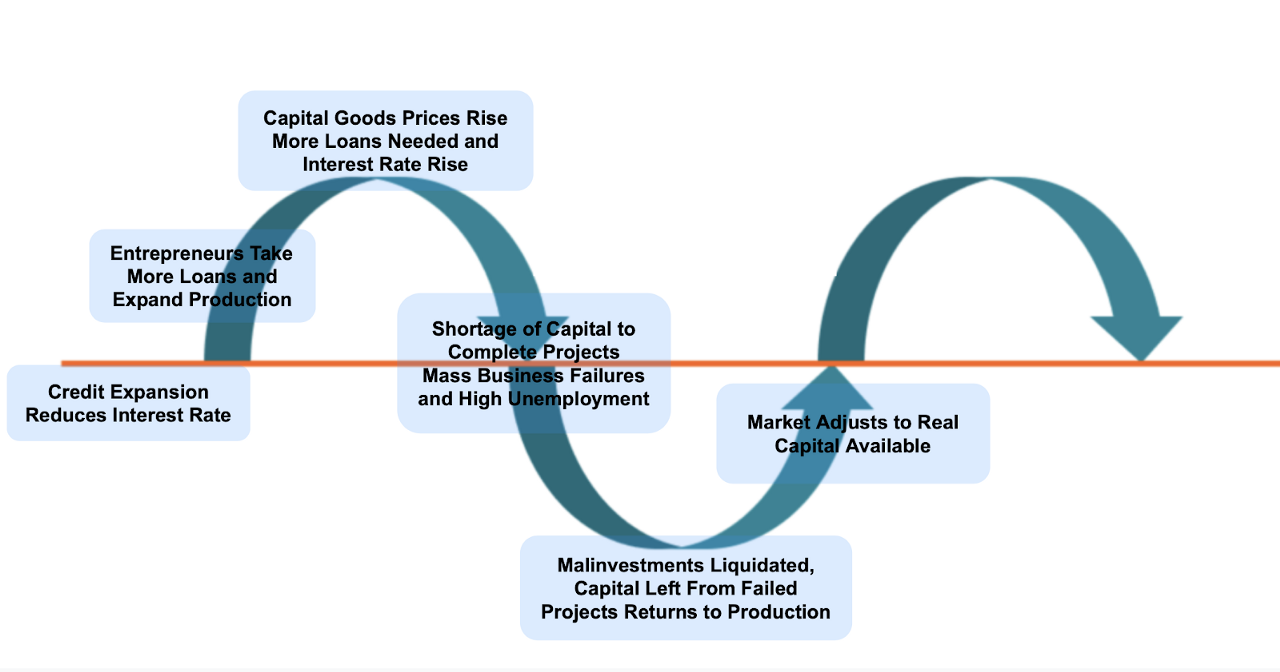

So what are the effects of such credit expansion on the process of economic progress we have discussed thus far? The initial effect from such credit expansion will be a drop in the interest rate. As the new money finds its way to (or, as usually happens, originates in) the banking system, banks will be in a position to offer cheaper loans, simply from having a greater supply of money available. This reduction of the interest rate has, for a long time, been the main (declared) objective of governments when pursuing credit expansion.

As we have seen, a lower (natural) interest rate is indeed correlated with economic growth, as it reflects lower time preference. From this, many economists have taken the leap to the conclusion that a lower interest rate promotes economic growth, and that it is therefore the government’s responsibility to push it as low as possible. However, we know that the interest rate is not like a metric on a machine, it is the reflection of the time preference of people. Attempting to promote economic growth by lowering the interest rate with credit expansion is like trying to “promote” rain by pushing down the pointer on a barometer. You will achieve nothing more than rendering the barometer defective and cause those who rely on it to make wrong projections. This is exactly what happens with the interest rate. As we said, entrepreneurs and businessmen rely on the interest rate to determine the length and complexity of their production efforts. The interest rate is their indication for how much capital is available to use for production. As central banks lower the interest rate, it lures entrepreneurs into expanding production and to commit to more roundabout processes than they otherwise would have taken. It distorts the economic data guiding entrepreneurs, leading them to make systematic errors, and ultimately misallocating capital.

At first, the expansion in production will cause an apparent economic boom, with more businesses opening, new constructions launching, wages rising and a general increase in economic activity. Nevertheless, this economic boom is necessarily unsustainable, as it relies on a defecting indicator for capital availability — the artificially low interest rate.

The essential problem caused by the artificially low interest rate is that it creates the illusion that there is more capital available for production than there really is. A “real” drop in the interest rate comes from a drop in the time preference of people, from the greater accumulation and saving of capital. The price system is the information system of the market economy, and the interest rate is the indicator informing entrepreneurs of changes in savings, in the capital available for production. However, when the government artificially lowers the interest rate, there is no change in the available capital. People did not reduce their consumption, nor did they increase their savings in any other way. There is no new capital to use in production, but with the artificially lower interest rate, entrepreneurs already rely on the existence of such additional capital in order to complete their expanded production processes. In other words, the increase in production started during the boom is unsustainable, it is impossible to complete, and will therefore have to end with a collapse.

But let us take a moment to see what this process would actually look like. With lower interest rates, as we said, entrepreneurs will expand production. They will take on new loans and use them to buy more capital goods. Now, since the supply of capital did not increase, but the demand for it from entrepreneurs rose, the prices of capital goods will have to rise to match the new demand. As the prices of the higher order goods rise, entrepreneurs will be forced to take new loans to obtain the capital they need to complete production. There will be a higher demand for loans and the interest rate, still artificially low, will be pushed back to the level where it corresponds to the true time preference of people. With the interest rate back up, and with the prices of capital goods adjusted to the new money supply, the shortage of capital to complete all production becomes apparent. The submarginal projects started during the boom, or malinvestments, as Mises called them, will again appear as unprofitable and will have to be liquidated. The final result of this process is a massive collapse of businesses across all the economy and a consequent high unemployment, that is, a recession.

During the recession, malinvestments are liquidated, and the capital invested in them is either lost or reallocated to more profitable projects. The recession is, in a sense, the re-adjustment of the market to the real capital and time preference of people. It is the market curing itself and recovering, wiping out the mistakes made on the basis of distorted information, stopping to waste scarce capital on unrealisable projects, and reallocating capital based on the corrected information.

In short, the business cycle is a period of unsustainable expanded production, induced by lower interest rates, followed by the realization that the expanded production is unsustainable, and the consequent collapse of businesses.

So what can we do to stop the recession? Unfortunately, once credit expansion has started causing the illusory economic boom, the eventual bust is inevitable. Capital is being wasted, and there is no way to make such malinvestments truly sustainable. Yet, basing their efforts on a different theory, governments and central banks still believe it is possible to artificially “combat” the recession by accelerating credit expansion even further. However, their repeated failures to handle those cycles leaves us a very good reason to question their theories and approach.

If the government pushes credit expansion even further, it will be able to reduce the interest rate again, essentially returning us to the first step of the cycle, but with the malinvestments made continuing to waste additional capital. Still, it is crucial to understand that they cannot do this forever. The boom is unsustainable, and preserving the malinvestments it induced by lowering interest rates at an accelerating pace will not change this fact, but only postpone it from being exposed, further delaying an amplified and inescapable market adjustment. Eventually, either capital is exhausted or a hyper-inflation ensues.¹⁶ Delaying the bust only aggravates the issue, causing a greater bust later, as it allows malinvestments to continue to waste scarce capital.

As the cycle becomes inevitable once the interest rate is distorted, the only way to stop the business cycle is to prevent interest rate manipulations. That is, we must prevent credit expansion from taking place. This is the approach taken by the Austrian economists, of which many, including Mises himself, suggested such reforms for preventing credit expansion. These were usually along the lines of returning to a rigid gold standard, having free market competition in money, or making large banking reforms, but among all their proposals, two, unfortunately contradictory, things are common.

First is their goal — their essence is limiting the power of governments and their control over money and credit. Second is their practical approach, which essentially amounts to limiting the government’s power *by asking the government* to limit itself. Such a thing is quite unprecedented. Governments will not voluntarily reduce their power over anything, nor will they admit of making such a huge mistake as causing business cycles for so many years, as adopting any such proposal must mean.

Many of the Austrian economists have realised this fault in their works to achieve any practical result, which led Friedrich A. Hayek, Mises’s most well-known student, to the following conclusion:

“I don’t believe we shall ever have a good money again before we take the thing out of the hands of government, that is, we can’t take it violently out of the hands of government, all we can do is by some sly roundabout way introduce something that they can’t stop.” — F. A. Hayek

This is precisely where Bitcoin comes in. While Hayek’s quote is from 1984, about two and a half decades before Bitcoin was invented, hardly anyone has ever described Bitcoin better than that. The idea of Bitcoin, as Satoshi wrote, is to create “a peer to peer electronic cash system”. That is, money which is operated by a global and open network, without depending on any central authority. No single participant or a specific group is necessary for operating Bitcoin — no one can shut it down, because there is no one Bitcoin depends on to continue to work. It is as Hayek said, a system which takes “the thing” (money) out of the hands of government, and that they can’t stop.¹⁷

This is the most important difference between Bitcoin and gold, which most Austrians still currently endorse. The gold standard was operated by governments and banks, and cannot work without such a system of a few central institutions holding most of the gold reserves. Without such a system, all gold payments will have to be physically delivered. Such an option was already impractical decades ago, but today, with all the digital payments made, it is just unthinkable. This means that the gold standard can only function if approved by governments, but is doomed as soon as the political attitude shifts unfavourably. It is this very weakness of the gold standard that enabled governments to effectively confiscate it (Executive Order 6102) and eventually completely remove it (Executive Order 11615). This weakness of gold is what Bitcoin aims to fix. It is “an unstoppable force” — money which does not ask for permission from politicians to operate.

Bitcoin and the Business Cycle

But assuming for a moment the use of Bitcoin as money, there is still the question of how would it help prevent the business cycle? Bitcoin has a few notable attributes in this regard.

First, Bitcoin has a predetermined fixed supply limit. It is produced by a mechanism of proof of work, a digital “gold mining” like process, and limited to 21 million units ever to be created. This is slightly different from gold, where mining can continue to unknown extent, but the important property they share is that their supply cannot be manipulated by government decree. No paper signed by politicians could make more Bitcoin or gold appear, unlike the system of fiat money we have today. This means that, with Bitcoin, governments will not be able to inflate the base supply of money. This is the first necessary step towards limiting credit expansion in the economy. But, while necessary, it is not enough by itself, as it still does not directly limit the ability of banks to expand credit.

This leads us to the second important way by which Bitcoin could help prevent the business cycle, and on which we have already touched briefly. It is the fact that Bitcoin works without intermediaries, it is peer to peer cash. It allows people to hold their money by themselves, without having to give (more correctly, lend)¹⁸ it to a bank to be able to make transactions. This will ensure a clear separation between money held by individuals for their regular expenses (as cash balances), and the money they wish to save and can be invested productively in the economy through the banking system. In other words, it could limit the part of the money, the reserves, held by banks, thus limiting their power to excessively expand credit. When people can use their money — without relying on financial institutions to make the transactions — they can choose what amount they wish to hold themselves to transact from, and what they prefer to save and invest in the economy, and entrust banks with managing the latter. Such a system will make sure that the supply of money and money substitutes (credit) in circulation remains stable, preventing credit expansion and the consequent business cycle.

Even if banking for “demand deposits”, that is for money held for regular expenses, continues, the fact that Bitcoin has a rigid supply will force banks to be responsible with their credit issuance or they will risk a bank run. Furthermore, since Bitcoin is a digital asset, it is much cheaper to store, verify and transfer than with physical assets. That is, Bitcoin does not need a Fort Knox to benefit from economies of scale in storing and handling it. Therefore, the barriers of entrance for new competing banks will be lower, and there will be better grounds for free competitive banking. This improved competition could force banks to be more responsible in managing reserves¹⁹, thus limiting credit expansion more effectively even in such a “free banking” scenario.

The Road Ahead

Now that we see the main economic reason for transitioning to Bitcoin, we can discuss how such a transition could take place. In fact, I would argue that this transition has already started. In just about a decade, Bitcoin has grown from being a mere idea on a mailing list to a global network serving millions of people, having cleared trillions of dollars worth of transactions. Many businesses have already started accepting it, people are hodling it, and we may even say that there is a new, alternative, financial system already developing around it. Despite the impression some people get from its short-term price volatility, the trend is clear, Bitcoin is going forward. It is not waiting for politicians to approve it (like gold or Libra do), or central bankers to adopt it, or for “economists” to embrace it — it is growing in spite of their current objections.

This present trend though is by no means inevitable. While it is unlikely that Bitcoin itself can be stopped, its adoption could very well be. In the end, Bitcoin is just a tool available for people, but it is the public which decides if they wish to pick it up and use it. Like with all other economic and political changes, the success of Bitcoin depends on public opinion. It is not enough that we have Bitcoin if people don’t see its benefits, or refuse to use it. Unfortunately, the most prevalent views of today, both in economics and politics, see Bitcoin as useless, harmful and even “evil”. The idea of money not controlled by the state is rejected by all popular doctrines of today, and the only view somewhat receptive to it, that of the Austrian school, has been on the losing side of public opinion for many decades.

However, it seems that together, by combining Austrian economics as a theoretical framework, with Bitcoin as the practical approach, we could have an incredible opportunity to sway public opinion. While the Austrian framework provides the theoretical explanations of the benefits of having sound, hard money, Bitcoin demonstrates them in reality. And while it is unclear what further consequences would result from adopting Bitcoin, the Austrian approach to economics can clarify that. The Austrian view is the only one which is able to provide an explanation for the success of Bitcoin, and even simply for its existence. In other words, Bitcoin exposes the public to the possibility of having a different kind of money, not controlled by the state, while the Austrian theory explains why such money can be so beneficial and desirable. Every day in which Bitcoin continues to operate is a slap in the face of the mainstream economists. It is a living proof that their theories might not be right after all. That the free market does not need the state to set and manage the money, and can produce a better monetary system by itself.

Conclusions

To briefly summarise, the unique properties of Bitcoin — being digital, peer to peer, unstoppable hard money, have the potential to make a real transformation in the economy, preventing the business cycle and allowing for sustainable economic growth.

For millennia, governments were entrusted to manage the money for their citizens, but history is flooded with examples where this power was abused.²⁰ While in the past, such abuses were shameful acts committed secretly by rulers against their citizens (like coin clipping), today — in the age of populism — the rulers are no longer ashamed of it, but to the contrary, they proudly announce those acts, backed by the “intelligentsia” providing excuses for how this is done “for the people” to “stimulate the economy”.

As Mises explained on the essence of sound money:

“It is impossible to grasp the meaning of the idea of sound money if one does not realize that it was devised as an instrument for the protection of civil liberties against despotic inroads on the part of governments. Ideologically it belongs in the same class with political constitutions and bills of rights. The demand for constitutional guarantees and for bills of rights was a reaction against arbitrary rule and the non-observance of old customs by kings. The postulate of sound money was first brought up as a response to the princely practice of debasing the coinage. It was later carefully elaborated and perfected in the age which — through the experience of the American Continental Currency, the paper money of the French Revolution and the British Restriction period — had learned what a government can do to a nation’s currency system.” — Ludwig von Mises

Money is the backbone of the market economy, it is what coordinates the action of everyone, which is why it must be neutral — resistant to manipulations and forced debasements. It is time that we take the thing out of the hands of the state, back into the hands of the people. It’s time to move to Bitcoin.

This article is based on a lecture given at the Value of Bitcoin Symposium which took place in March 2020, Vienna. The full video of the lecture is available here

Special thanks to Ben Prentice (mrcoolbp), David Lawant (DavidLawant_BTC), Emil Sandstedt (bezantdenier), Keyvan Davani (keyvandavani), Thibaud Marechal (thibm_), and Stefanie von Jan (stefanievjan) for all the feedback I received from their reviews, comments, and suggestions which helped me shape this article.