Welcome to prepping, Bitcoiners

| If you find WORDS helpful, Bitcoin donations are unnecessary but appreciated. Our goal is to spread and preserve Bitcoin writings for future generations. Read more. | Make a Donation |

Welcome to prepping, Bitcoiners

By Preston Byrne

Posted March 31, 2020

Posted on March 31, 2020 by prestonbyrne

I’m a Bitcoiner, libertarian, and somewhat of a prepper. There’s a lot of overlap between the three communities. I’m not quite sure why.

Part of it might be down to the fact that these groups tend to look upon large-scale structural features of our societies, such as central banks or sovereign debt piles, with a considerable degree of suspicion, correctly identifying that debt is itself a form of political risk reallocation and, as with all risk, increasing the amount of risk in a system makes it vulnerable to stress.

With that in mind, I think it’s OK to now say that mild prepping is no longer some loony fringe hobby. As we see that the basic, “boomer” assumption that modern, technocratic government will always have the capability to handle a crisis is wrong, we also see that individual people and companies who were prepared for this crisis were in the best position to assist with ending it. See, e.g., MyPillow, GE, and GM at the corporate level, or people who got off of the streets and went into quarantine in the first week of March on a personal level.

Companies that carried large debt loads or frittered away their cash on stock buybacks appear fragile and brittle in the face of a 12-standard-deviation demand shock. This will likely set a new baseline across our society – both in business and personally – where savings, thrift, and resiliency, even if inefficient, become higher priorities among individuals, businesses, and governments.

Comprehensive risk management is, when applied to individual life, referred to as “prepping.” The benefits of “prepping” are that when a global disaster like Covid-19 strikes, the only errands you need to run are (1) to a low-tax liquor store on the Delaware state line and (2) to one’s local Staples to pick up printer ink, rather than joining the hordes of Americans fighting over the last boxes of rigatoni and minute rice.

On a personal level, I am sure – Twitter reveals all – that many of you in the Bitcoin world are now venturing into the preparedness universe for the first time.

Neeraj is the crypto meme master. He is not a farmer. And he’s totally into this. Then there’s his colleague, Peter:

Originally I thought Peter was a neophyte to this but I’m now advised he’s been into permaculture for awhile.

This is awesome. People are getting into self-sufficiency and people who are into self-sufficiency are starting to talk about it more.

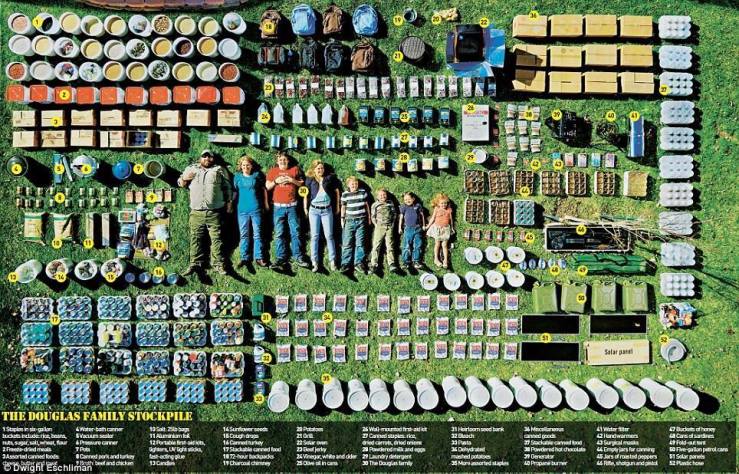

New people should be warned, however, that there is an entire industry dedicated to prepping and, more particularly, selling you a bunch of preparedness crap that you probably don’t need. In keeping with the financial preparedness piece of the equation, you shouldn’t spend a penny more than you need.

To paraphrase the Adam Smith Institute’s Madsen Pirie, before Covid-19, prepping was considered lunacy. In the future, it is likely to be policy, at all levels of society.

It’s something I’ve tried to apply in my personal life. Here’s how I went about it.

1) Eliminate debt loads.

The best thing you can do from a preparedness perspective is to eliminate all debt, particularly if it carries a high rate of interest. This will allow you to save and invest.

2) Preparedness is a way of life, not a line-item.

Until recently I ran a small law firm on my own. During that time I kept my burn rate very low by, e.g., setting up shop in Connecticut rather than New York. My aim was to always have several months’ worth of opex in bank so I could survive if the phone stopped ringing for a few months.

Fortunately, that never happened. At the outset of the Covid-19 crisis, I was a little shocked to learn how narrow other businesses’ margins were. (Although admittedly when I first started working for myself I wasn’t planning for demand shocks, either.) I learned the hard way that runway is life during (a) my days as a startup founder, where survival and successfully closing venture investments was highly correlated and (b) my days after running a startup when I had to stretch out my savings while requalifying as a lawyer in the United States and unable to work.

After realizing that whatever safety net you thought you had by virtue of living in a modern, Western country was a figment of your imagination, you’re never quite the same. You cannot fix this problem with a single transaction. You have to change the way you do business. All of American society is now experiencing _austerità _for arguably the first time in nearly 100 years, and realizing that it, too, under certain circumstances, has no safety net.

“Money printer go brrr” may be working this time, but it can’t work forever. It is not a sound basis for society-wide risk management. I predict that, once this crisis is over and people begin getting back to work, saving rates will soar. With good reason.

3) Start small by building an EDC loadout.

De-risking is the accumulation of many small decisions rather than a few big decisions. Like stacking sats, except you’re stacking stuff.

This is a lot of work. Don’t try to do this overnight.

This is a lot of work. Don’t try to do this overnight.

You have to be cheap enough, but not too cheap. There are limits to cheapness. When I was in London during the Great Recession of 2008-09, for example, one law firm was rumored to have decided to slash costs by sending all mail via Second Class post, which was not a good idea (this decision was, apparently, swiftly reversed when the firm realized that the postal/mailbox rule in England only applies to First Class post).

Fortunately, you don’t need a ton of gadgets and junk to be ready for most situations. You should have some tools.

I recommend that folks who are totally new to this start with only a handful of things by building what I call an everyday carry, or EDC, loadout. This includes basic stuff like hex keys, a multitool, a flashlight and spare batteries, a utility knife if laws in your jurisdiction permit (in England or NYC, for example, this would not be a smart idea), a lighter or two, maybe something for water filtration, and a small case in which to keep these things.

If you’re not accustomed to having any of these things around, after doing this, what you’ll find is that situations start coming up where before you didn’t have the right tool but, suddenly, now you do.

My typical EDC loadout. A flashlight identical to this one is on my person at all times. The rest of this stuff is usually nearby, either in a bag or the center console of my truck.

My typical EDC loadout. A flashlight identical to this one is on my person at all times. The rest of this stuff is usually nearby, either in a bag or the center console of my truck.

Keeping a toolbox in your car or office is also probably a good idea. Car kits can be built out with useful, but bulkier, things that you might not want to drop into a briefcase or backpack but would want nearby, like jumper cables, 12 volt DC-AC converters, spare battery packs, and small electric air compressors. You will wind up using them at some point.

To be perfectly frank, a multitool, a good set of allen wrenches, a flashlight, and a set of jumper cables was enough to handle virtually any real-world problem I had until Covid-19. My guess is that the same will be true for you.

4) US government guidance is woefully inadequate, and purveyors of survival kits, citing that guidance, will try to rip you off.**

FEMA’s official guidance states that every person in the United States should keep at least 72 hours’ worth of non-perishable food and other necessities (batteries, etc.) for themselves and their families immediately available.

By implication FEMA also says that businesses should also be prepared for 72 hours’ worth of disruption. As the current crisis shows, however, 72 hours is simply not enough to deal with crises of the scale modern Americans may expect to face. From a business perspective, if you can’t cover your expenses for more than 72 hours, you need to cut expenditures somewhere or open up a revolving liquidity facility.

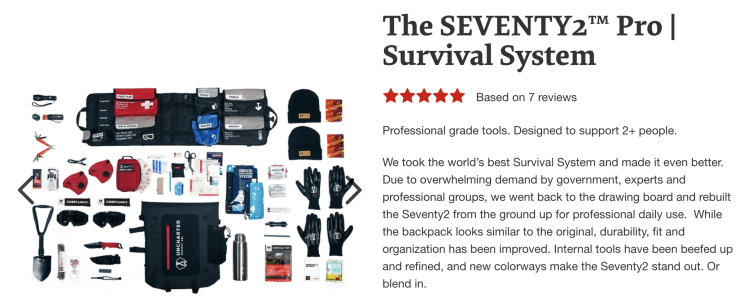

From an individual perspective, your first task on your prepping journey will be to assemble these supplies. One thing you may encounter as you embark on your preparedness journey is a concept known as a “bug-out bag” which holds 72 hours’ worth of stuff and a first-aid kit. You should have one.

In online prepper circles, bug-out bags are a serious topic of conversation, because these bags are regarded as the ultimate grab-and-go survival tool you’re able to have with you at all times. I keep mine in the back of my truck. Much digital ink has been spilled over what the exact contents of these bags should be, how much they should weigh, or even what they should look like, with some adherents preferring tacticool MOLLE bags and others preferring more subtle I’m-weekending-in-the-Hamptons-nothing-to-see-here duffels.

Some companies sell luxury 72-hour bug out bags full of generic crap for $500 or more.

Overpriced

Overpriced

You do not need these expensive kits. You can build them on your own, with better equipment, for a fraction of the cost and with negligible effort using sites like Amazon.com (although I always recommend going to local shops first if you possibly can). Check out sites like The Prepared or graywolfsurvival to see how the prepper OGs developed their “bare minimum” supply lists. What works for them may not work for you. Decide what works for you.

FEMA’s 72-hour guidance is, very clearly, obsolete. That doesn’t mean you shouldn’t follow that advice as an absolute bare minimum level of personal risk management.

In my opinion you should probably keep enough on hand to survive for two weeks rather than 72 hours, and you should store it in a trunk rather than a bag.

Part of “bug-out bag” theory is that it’s supposed to be something you literally grab as you’re on the way out the door, fleeing a disaster. Unless your house is literally on fire, in the United States it is unlikely that a major crisis like Covid-19 will emerge so quickly that (a) you are unable to get to a vehicle and escape and (b) you’ll have no time to retrieve some belongings. Considering that grocery store supply chains are continuing to work even in the Covid-19 crisis, if you keep a bag in your car, and a trunk in your house or apartment, chances are pretty good you’ll be ready for most disasters life throws at you short of an asteroid strike or nuclear war.

More preparedness is better than less. My personal preference is to keep a bag in the car and few weeks’ worth of stuff in the house that I’ll actually eat, so nothing is wasted and it’s possible to rotate things out well before they expire.

5) Don’t over-prepare.

FEMA’s official guidance for the Pacific Northwest is beefier than its guidance for the rest of the country, recommending that all citizens there maintain a 2-week supply of life’s necessities. This is good advice and, in my view, a good objective for most Americans to have.

This determination was informed by a 2017 disaster preparedness exercise code-named “Cascadia Rising.” Cascadia Rising simulated the outcome of an extremely large, so-called “Megathrust” earthquake off the coast of Washington and Oregon. That earthquake – the occurrence of which, like a global pandemic, is an absolute certainty on a long enough timescale – is predicted to register an almost incomprehensibly large 9.0 on the Richter scale and is expected to completely destroy most of the PNW west of I-5.

In theory, it seems sensible to just order a ton of Mountain House freeze dried food, leave it in your closet and forget about it until disaster strikes. But this is expensive, and on Day 17 of lockdown, I have to say that the ability to eat real food – meat, vegetables, fruit – is really rather nice.

With this in mind, I don’t keep a ton of stuff stored 24/7/365. That would be a waste of effort and money. Instead, in the run-up to the U.S. outbreak I implemented what I referred to as a “ramp strategy” which, rather like the collateral management in finance, ramped up the level of security I had on hand as the risk of economic collapse increased.

To do this successfully you need to make information and time your allies. As long as you are a high-information citizen, you can spot threats ahead of time, and plan accordingly. As the risk of a catastrophe in the United States increased, my preparedness levels – which, admittedly, were somewhat higher than average – rose commensurate to the danger. When Wuhan was locked down, I prepared. When Venice was locked down, I prepared some more. When the U.S. crossed 100 cases, I prepared some more. As D.C. shut down, I added the finishing touches.

The following week, as America realized the jam it was in, I was fairly annoyed with the situation but was able to follow CDC guidance, stay home, and focus on work without needing to worry if I’d be short on crackers and tea.

The lesson from the Covid-19 crisis is not to run out and buy all the canned food in the world and allow it to languish in a pantry until the next disaster strikes. The lesson is to be flexible, which means clearing your debt load, living somewhat more frugally and to focus on tooling and capabilities (being able to filter and boil water, make a fire, charge a battery, change a tire) rather than stuff. Unless you’re trying to be 24/7/365 prepared for a surprise nuclear first strike which you expect to occur in the immediate future, keeping a permanent stock of food you’ll never eat isn’t a particularly smart idea.

If you’re smart, you’ll know ahead of time what you need to survive for [n] weeks and will be able to submit some very tailored orders via online shopping to address those needs before less-informed citizens begin to swarm grocery shelves. This should minimize the investment of time and the risks of unnecessary or wasted expenditures.

6) As bad as it is, Covid-19 is probably not “the big one.” It’s also probably the worst economic crisis you’ll ever experience.

As bad as this is, it could actually be worse. Covid-19 kills anywhere between 0.2% and 1% of those it infects. Contrast this with the plague, which kills 17% of those who contract it, or H5N1 influenza, which kills 56% of those infected. Ebola and Marburg viruses kill, in some settings, north of 80% of their victims.

That said, while being on Covid-19 lockdown is likely the worst thing anyone reading this blog post will ever have to experience, it almost certainly isn’t the last crisis we will ever experience – meaning we should take the opportunity to learn from it and build up resiliency in its wake.

A resilient society requires everyone to do their part to be personally prepared, so (a) you aren’t part of the problem when a crisis breaks out and (b) you have the means to remove others from the zone of danger when a crisis breaks out, both of which limit the burden on government and your reliance on government to continue carrying on your day to day life until normality is restored.