The Onion Model of Blockchain Security – Part 1

| If you find WORDS helpful, Bitcoin donations are unnecessary but appreciated. Our goal is to spread and preserve Bitcoin writings for future generations. Read more. | Make a Donation |

The Onion Model of Blockchain Security – Part 1

By Hasu

Posted April 11, 2020

Public blockchains are empirically secure. For most of their (admittedly, short) history they did what they were designed to do, processing transactions without any hiccups. That we can observe. It is harder to come up with a theory of why it’s the case.

Individuals typically explain their pet project’s security with whatever they personally understand and value the most. Depending on who you ask, a public blockchain is either secured by economic incentives, by globally distributed hashpower, by full nodes, or by a rabid community upholding a shared set of values. That’s not entirely surprising: The law of the instrument suggests that we over-rely on tools that are already familiar to us. If your only tool is a hammer, to tend to treat everything as a nail.

I don’t think any of the above factors can explain the phenomenon all on their own. It is too easy to come up with attacks that succeed in spite of perfect protection in one particular area. For example, in a network where all users run a full node, a miner could still replace the entire blockchain with an alternate one where he controls all of the coins. So it must be the combination and interplay of the different parts that generate the amount of security needed for a permissionless digital cash system.

The onion model of blockchain security

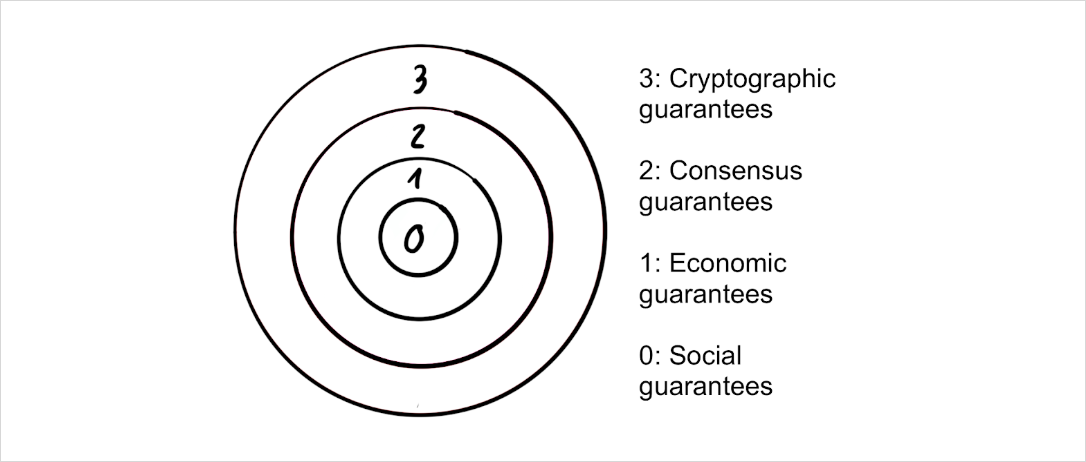

The model I propose hopes to synthesize the individual elements of security into a coherent picture. The goal is to look at public blockchain more holistically, detect strengths and weaknesses, and allow the comparison of different blockchains. The security of a public blockchain resembles an onion, where each layer adds additional security:

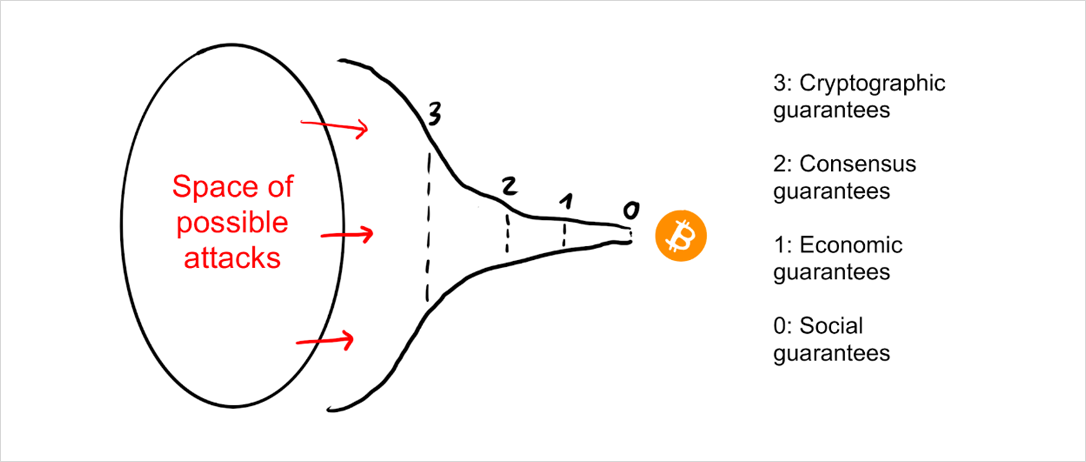

To permanently destroy a public blockchain, it is necessary to destroy the faith of users in its ledger state (the list of ownership) as well as the ability to reliably update that state going forward. All higher layers serve to prevent this from happening.

Attacks have to pass through this funnel of defensive layers before touching the core. We now discuss the layers one by one.

Cryptographic guarantees

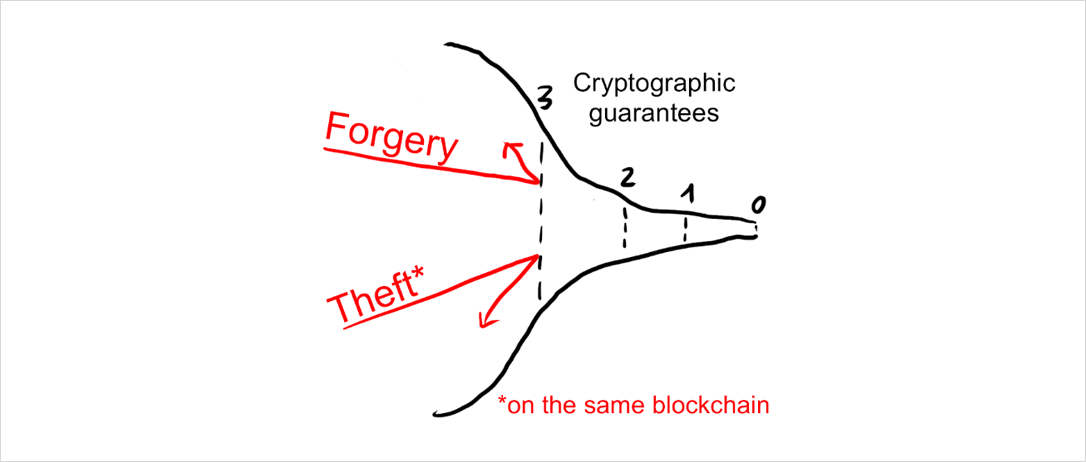

The outermost shield is provided by cryptographic guarantees. Cryptography gives the most reliable form of guarantee, so we want it to do the heavy lifting and prevent most attacks from the get-go. Cryptography ensures, among other things:

- No printing coins from thin air: All blocks (and hence all block rewards) must have a sufficient proof of work attached to them.

- No spending other people’s coins: Digital signature schemes ensure that only the valid owner of a coin can spend it.

- No retroactively changing the contents of old blocks: Hash pointers ensure that an attacker has to change all blocks built on top of any old block he wants to change.

All of these attacks are rejected by the first filter:

But while cryptography is very powerful, there are other assurances it cannot provide. For example, it cannot decide which of two equally long blockchains is the “correct” one (that would require knowledge about the real world, such as “which of them will other people switch to” and “which of them has the higher market value in the long-term”). It also cannot force miners to mine on a specific block, publish a block once they found it, or even ensure they include specific transactions.

Consensus guarantees

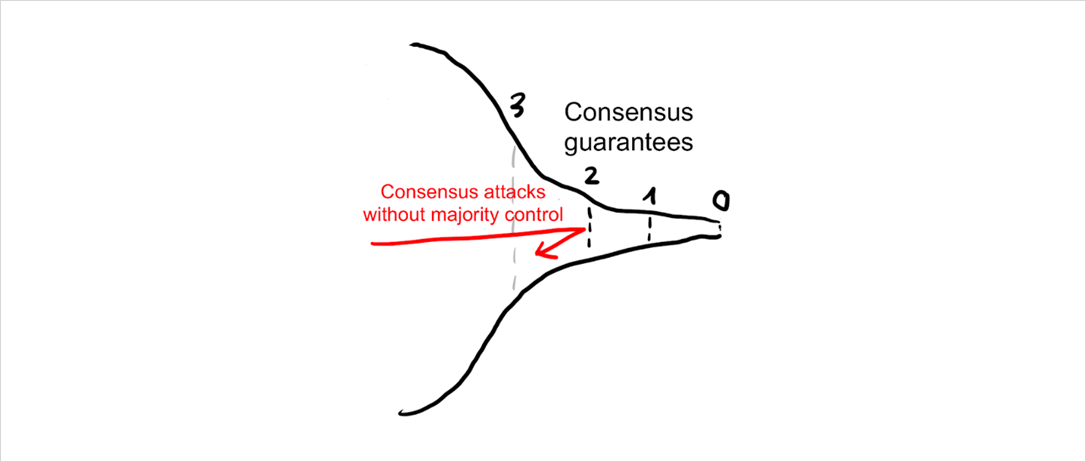

Some of the attacks that pass the first layer will be stopped in the consensus process. In Nakamoto consensus, nodes constantly observe the network and automatically switch to the longest (most expensive) chain. Miners only get paid if their blocks end up being part of that longest chain, so they need to converge with the other miners. As a result, there is a strong bias for miners to work on the tip of the blockchain because that’s where their block is most likely to become recognized by everyone else.

If a rogue miner wanted to mine on a previous block, he would enter a race condition with the rest of the miners who continue to work on the tip of the chain. Only if he finds several blocks faster than everyone else combined, he can catch up and then pull ahead. But depending on his share of hashpower, he is very unlikely to succeed with even a very shallow reorganization.

For an attack to work reliably, an attacker needs to first obtain control over the consensus layer. That means controlling either >50% of hashpower in proof-of-work, >33% of stake in BFT-based proof-of-stake, or >50% of stake in longest-chain based proof-of-stake.

The operational difficulty of this is often underestimated. For example, large governments are typically seen as the largest risk to public blockchains. However, if they wanted to buy the necessary hardware on the primary markets they would quickly find that annual production is capped by chip foundries in China, Taiwan, and South Korea. And their capacity is further capped by rare-earth mining in Australia, wafer production in Asia and Africa, and so on. There’s only a limited amount of capacity available every year, even for a highly motivated buyer. Acquiring the necessary hardware that way could take at least 2-3 years, and would not go unnoticed.

Only China could get to 50% hashpower by confiscating existing hardware or possibly coerce pool owners into launching a single attack. This could work, but only until individual miners start to notice and direct their hashpower elsewhere. While an attack like this is very unlikely to work against Bitcoin anytime soon, smaller networks command respectively smaller shares of hashpower or stake. In that case, the space of possible attackers can include smaller (rogue) governments as well as the entire private sector.

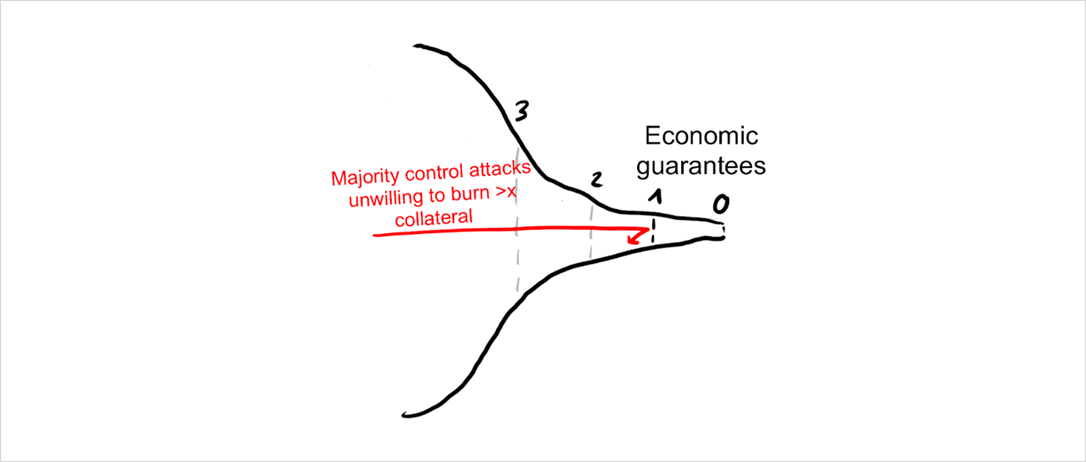

Economic guarantees

I’ve previously argued that thanks to economic guarantees, blockchains don’t immediately break if a single entity controls the consensus layer. By setting the right incentives, blockchains can associate a real-world cost with misbehavior. The ability to due that comes from the native token, introducing a concept of digital scarcity (and hence value) that can reward good behavior (with block rewards and fees) and punish bad behavior (either by slashing security deposits or by withholding future rewards.)

The size of these incentives scales with the level of control an actor has over the consensus layer. An actor who controls a lot of hashpower (even a majority) has proportionally more to lose from destroying the system. Thereby, attacks are discouraged with economic punishment for the attacker.

If a rogue miner wanted to mine on a previous block, he would enter a race condition with the rest of the miners who continue to work on the tip of the chain. Only if he finds several blocks faster than everyone else combined, he can catch up and then pull ahead. But depending on his share of hashpower, he is very unlikely to succeed with even a very shallow reorganization.

Not all economic incentives are made equal. A network with a larger block reward relative to network value is more secure because it forces miners to have more skin in the game. (This is why the declining block subsidy poses a risk to Bitcoin’s security).

Miners also have more skin in the game when hashing requires specialized hardware (so-called ASICs) that cannot be repurposed if the network disappears. It is no coincidence that all mining attacks to date have happened to smaller networks that subscribe to a fallacy called ASIC-resistance, where control can be acquired with little, or even no skin in the game (e.g. by renting hashpower).

Social guarantees

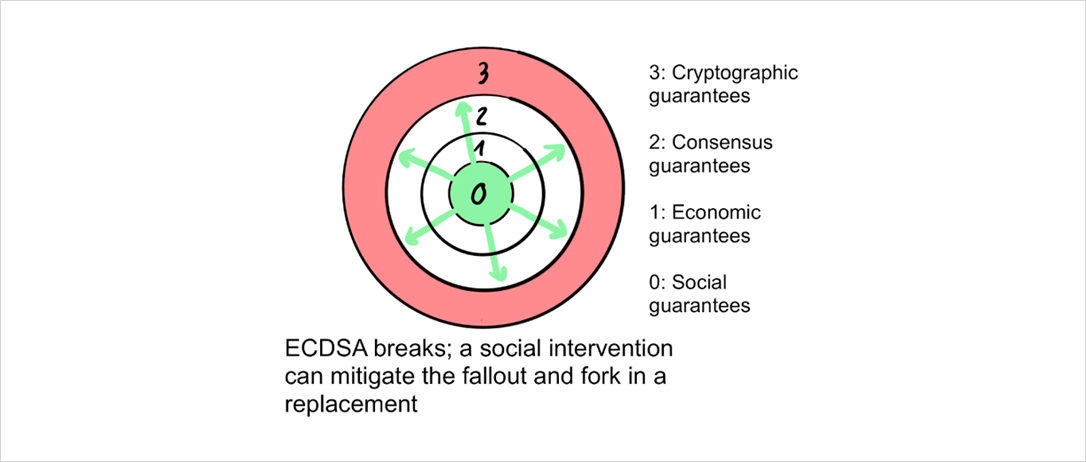

Previously we said that to permanently destroy a public blockchain, it is necessary to destroy the faith of users in its ledger state (the list of ownership) as well as the ability to reliably update that state going forward.

This is necessary because blockchains are not the ends itself. There’s no reason to pack up and go home because some parts of it failed temporarily. A blockchain is merely a means to automate the process of establishing a social consensus between its participants, a tool to maintain and update a shared database. The state of that database has value to the participants, and they are strongly incentivized to restore the system when it breaks.

For example, if the cryptographic hash function breaks, the social layer can come to a manual consensus (guided by technical experts) to replace the broken part:

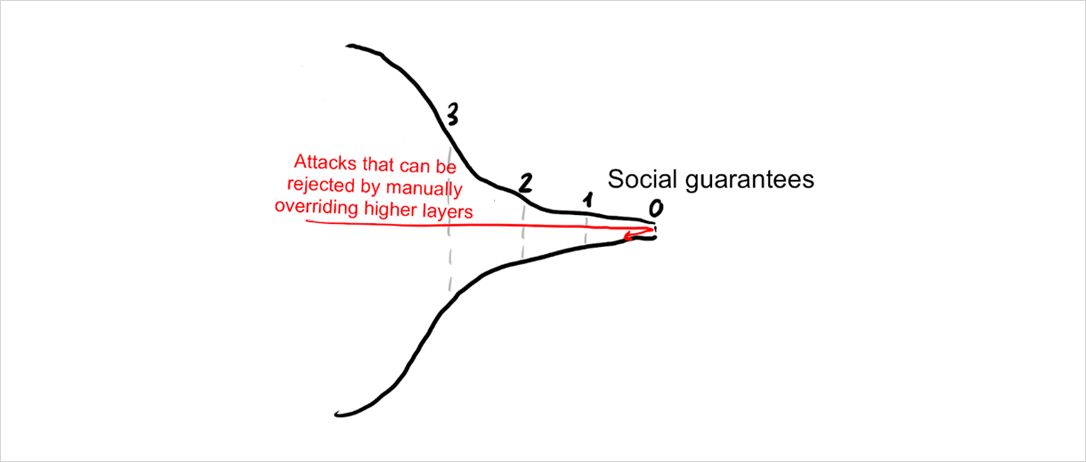

Likewise, if a consensus attack makes it past the stage of economic guarantees, the social layer can still manually reject it. If an attacker with majority hashpower started to DOS the network by mining empty blocks, in full acceptance of the economic damage to himself, then users could decide to change the PoW function and thereby remove that miner’s control manually.

As we can see, the only way to kill a blockchain for good is to either make users lose interest in the ledger state itself or damage the system to a degree that it cannot possibly be fixed.

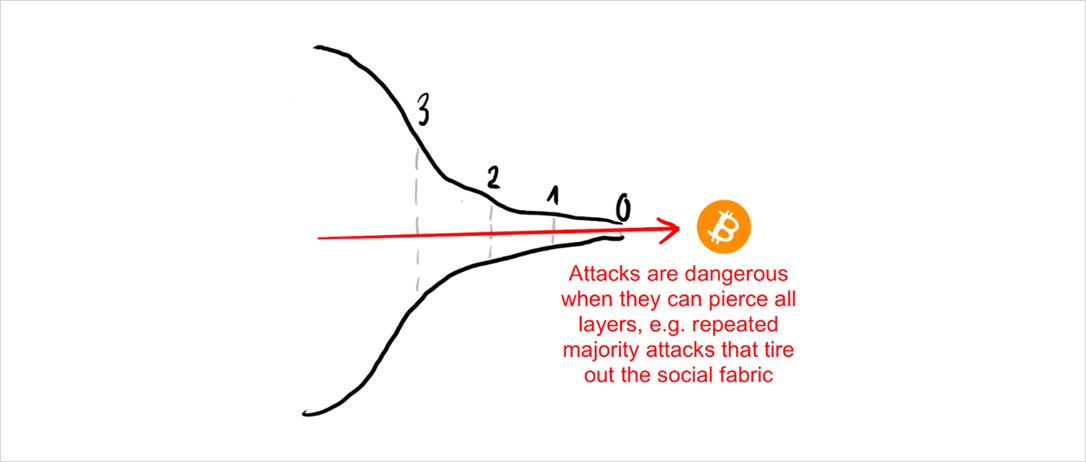

Attacks are dangerous when they can pierce all the layers and ultimately wear out the social core of the system until it can no longer override damage to higher layers and heal.

For both the healing and the manual intervention to work, the communities of each project need strong social conventions around their project’s main properties. In the case of Bitcoin, these core values are irreversibility of transactions, censorship-resistance, no backward-incompatible changes, and the 21m token cap. They serve as action blueprints for when social intervention becomes necessary, and create Schelling points around what needs to be fixed and what doesn’t.

These core values of a project are perpetually renegotiated, and not all users agree on all properties. However, the stronger the agreement around a particular value, the more likely it can be upheld during times of hardship.

Looking at the social layer as ground zero of any blockchain, we can see that social engineering attacks are a big threat. Higher layers become more vulnerable if rogue developers can sneak in detrimental code changes without supervision, particularly in projects with frequent hard-fork policies (recommended read on the topic).

Conclusion and future parts

I find the onion model useful to see how individual layers of a blockchain can create a secure whole. In some ways, it builds on my previous article on Bitcoin’s social contract: Any public blockchain starts from a set of shared values at the core, a blueprint for what the system hopes to achieve.

That set of values must be translated into rules of interpersonal behavior (the protocol!). Then we enforce these rules automatically, creating different types of guarantees: economic, consensus, and cryptographic. By constraining the behavior of its participants, the system becomes socially scalable, thereby enabling cooperation and hence wealth creation in low-trust environments.

Stay tuned for future parts, where we start applying the model to specific projects, starting with Bitcoin.