Stop comparing Bitcoin to the internet

| If you find WORDS helpful, Bitcoin donations are unnecessary but appreciated. Our goal is to spread and preserve Bitcoin writings for future generations. Read more. | Make a Donation |

Stop Comparing Bitcoin to the Internet

By Dhruv Bansal

Posted January 19, 2018

The market cap of cryptocurrencies dropped almost 50% from ~$820B to ~$420B in the last month. This is not the first time cryptocurrencies have experienced such significant losses (though it’s one of the fastest) and it certainly won’t be the last. Crypto-cynics and unfriendly media were jubilant in their choruses of “I told ya so”. There was much hand-wringing and regret expressed by some investors, especially those who only recently acquired their positions, who doubtless sold during the plunge.

Yet, throughout, there remained a population of crypto holders curiously unfazed by the debacle and the clamoring. These investors call themselves “hodlers”. They have held cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin for extended periods, some for many years, and they have weathered downturns like this before. Why did they buy crypto so early? How have they remained so serene when so many others in the market are panicking? Are they crazy? Or is blockchain a religion for them?

The answer is simple: hodlers recognize the true potential of blockchains and this allows them to adopt the long-view on their cryptocurrency holdings. Like value investors, short-term pullbacks in price mean little to them. Rather they relish when prices collapse because it lets them acquire more coins, cheaply.

In this article, I will provide a historical analogy for blockchains which will help you adopt the long-view on cryptocurrencies.

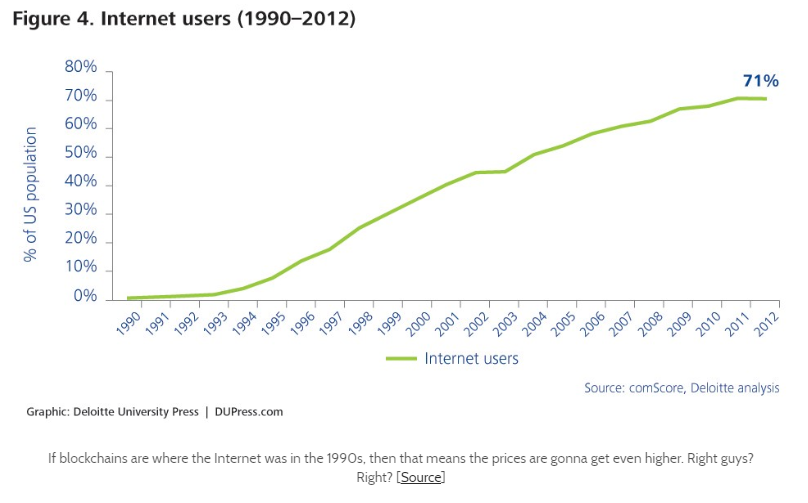

But first, we must dispense with an analogy you might already be familiar with: blockchains are like the Internet in the 1990s.

It’s not an uncommmon insight:

And it’s true: the “Internet in the 1990s” really is a good historical analogue for the blockchain in many ways. Blockchains are digital, networked, and will change society, just like the Internet did, so the analogy is sticky. And who didn’t love the 1990s, amirite? A 32-bit era of wunderkind programmers evolving crazy, ambitious startups to speciate a new niche. Crypto-pimps and cheerleaders love using the Blockchain::Internet analogy, because it suggests fantastic, abundant, imminent growth. Invest!

The diligent remember that most tech startups of the 1990s would eventually fail, even some which had tremendous funding. The NASDAQ spike and crash reminds older investors of the “Bitcoin bubble” or mania over ICOs. Crypto-cynics and haters love the Blockchain::Internet analogy as well because it suggests caution and the need for due diligence in the face of irrational exuberance. Caveat emptor!

Both of these perspectives on the Blockchain::Internet analogy are correct. Like the Internet in the 1990s, blockchains are poised for tremendous growth, so investing in the right tokens & teams may yield once-in-a-generation returns for investors (the crypto-equivalents of Google, Amazon, Facebook, &c). Yet many (most?) current projects will probably still fail (Pets.com, Webvan, eToys, &c.).

But both these perspectives are also dramatically wrong. Comparing blockchains to the Internet actually undersells the eventual value of the industry and the impact it will have on humanity.

No, the best analogy for the blockchain is not the Internet, but the lowly telegraph. In order to understand why, let’s first discuss the telegraph and the technologies that evolved from it.

A modern view of the telegraph

Historical woodcut of a telegraph operator transmitting some dank memes (1839). [Source]

Most people know what a telegraph is (or was): a tappitty-tap electronic gizmo that allowed historical, mustache-oriented peoples to send each other the old-timey equivalent of LOL ROTFLMAO.

But allow me to offer a different perspective. The telegraph was the first example of a new category of technology:

The telegraph was the first telecommunications technology: it enabled humanity to transmit digitally encoded information at (near-)instant speeds over long distances using a privately owned network.

Let’s unpack that sentence a bit:

- telecommunications: The telegraph was the beginning of the telecommunications industry (ignoring for now earlier, more manual methods such as firing cannons, waving flags, or flashing lights over relay networks of manual operators).

- digitally-encoded information: We are referring to Morse code, of course, the bebop-doo-wop binary line noise of the telegraph’s protocol. Telegraph operators transformed users’ thoughts and words (themselves already a discrete encoding of sorts) into these data structures before they could flit along the network.

- (near-)instant speeds over long distances: Data transmission through telegraphic wires was (is) so fast that it may as well be called instant (we are neglecting here the practical/engineering issue of needing repeater-stations manned by human operators taking a finite time to repeat each message, but please, forgive us our trespasses into falsehood in pursuit of narrative).

- privately owned network: Telegraph networks were capital-intensive projects with limited throughput, so their private owners charged usage fees.

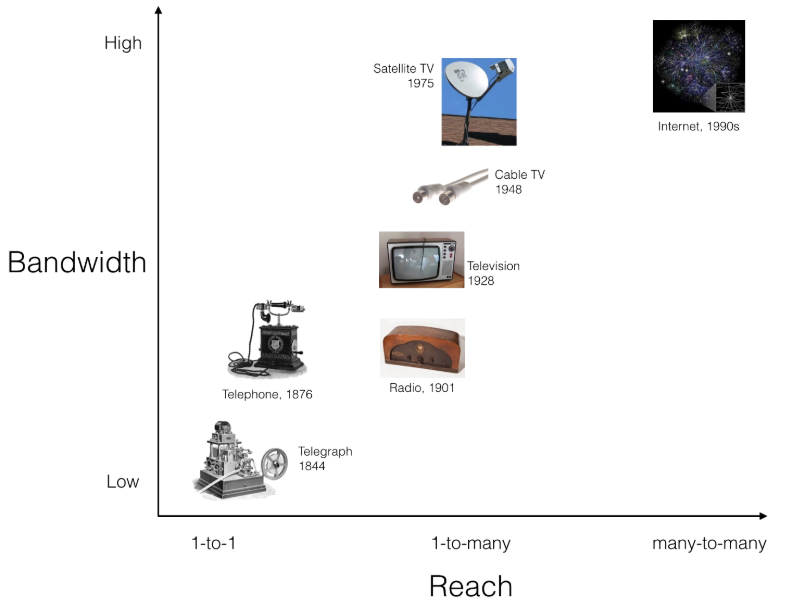

The Internet is the pinnacle of modern telecommunications, but it also the logical and inevitable outcome of the technological and social change started by the telegraph (1844):

- (1876) The telephone brought telecommunications directly into people’s homes and allowed for the direct transmission of audio in addition to just textual characters.

- (1901) The radio introduced the use of the wireless electromagnetic spectrum to transfer data instead of physical telegraph wires. This allowed for one-to-many transmission, enabling content such as entertainment and news beyond just one-to-one, direct communication.

- (1928) Television introduced the digital representation of visual signals in addition to just text and audio.

- (1948) Cable TV and satellite TV (1975), introduced even greater bandwidth and greater speeds and supported more content with greater variety.

- (1990s) The Internet integrated all of these improvements and expanded discourse from one-to-one and one-to-many to many-to-many.

Telecommunications has come a long way in 170 years, increasing reach and bandwidth by orders of magnitude. But it all started with the telegraph. [All images from Wikipedia]

If there were an extremely wise and forward-thinking person alive in 1844 when Samuel Morse sent the first real telegram (WHAT HATH GOD WROUGHT? — totally metal) 44 miles from Washington D.C. to Baltimore, could they have anticipated the Internet? Could they have remarked: Reginald, darling, what if we use light instead of wires, digitally encode audio and video in addition to just text, increase the bandwidth tremendously, and allow everyone to individually send and receive messages from wherever they are?

No technology is an island

It would have been extremely difficult for an 1840s telegraph enthusiast to predict the Internet. The evolution of telecommunications did not happen in isolation from all other technological and social change. It was driven by, and drove, the parallel evolution of other industries, most importantly energy, transportation, and computing. Without cheap and ubiquitous energy or global supply chains, how could we have built communications satellites or iPhones?

But all of these parallel industries already existed, in some rudimentary form or another, by the mid-19th century. The telegraph itself demanded a thorough understanding of electromagnetism, crude oil was being refined from paraffin, combustion engines were in industry, and the Jacquard loom had been long-operating. In each decade following the introduction of the telegraph, these technologies combined to create a more fast-paced, connected, global world with a greater need and desire for instant communications.

The details may have been fuzzy, but to those who saw the telegraph as the first member in a new category of telecommunications technology, the future was clear: a smaller, more connected, but more centralized planet. Some futurists of the time even got pretty close:

So why are blockchains like the telegraph?

Why do we believe the telegraph is the best analogy for blockchains?

It’s because blockchains, just like the telegraph, are the first example of a new category of technology:

Blockchains are the first distributed consensus technology: they use cryptography to enable global coordination through collective self-interest instead of centralization.

Let’s unpack this definition, just as we did for the telegraph:

- distributed consensus: This combination of technology and social movement is historically new, and Bitcoin’s blockchain is the canonical first example.

- cryptography: Public/private keypairs, hashpower, Merkle trees, &c, are cryptographic tools designed to create or correct imbalances in power between attackers and defenders, spammers and validators, governments and citizens, &c.

- global coordination: Blockchains are distributed systems. They have no inherent saturation size and can (eventually) scale to global demand. Their consensus algorithms (Proof-of-Work and Proof-of-Stake) are completely opt-in and provide coordination without control or coercion.

- collective self-interest instead of centralization: Successful blockchains use valuable tokens to create strong local incentives in delicate balance from which beneficial collective behavior can emerge. There are no centralized committees or official leadership hierarchies.

If you accept the argument that blockchains are a new category of technology, then the next question to ask is, “Where does it go from here? What will our world look like when Bitcoin is as old as the telegraph?”

The Distributed Future vs. the Centralized Past/Present

This question can’t be answered in isolation. The telecommunications industry arose alongside the energy, transportation, and computing industries. These are all democratizing industries, but they are also centralizing industries: they each created greater access for the average person but in a way that created ever greater inter-dependency on an ever fewer number of global firms. These industries are all capital-intensive, and cartels and monopolies have risen and been disrupted again and again as market share vacillates during and consolidates between cycles of innovation.

Blockchains weren’t developed in a vacuum. The principles of robustness, trustworthiness, anti-fragility, and independence through distribution which drove cypherpunks to build Bitcoin are active in other industries today. If we are to predict the future, it is these industries we should consider alongside blockchains:

- Green energy will save us from cooking ourselves to death. But it is also a stimulus towards distribution. Energy is thermodynamically expensive to move around, and so it is vital to capture it near where it is being used. Our existing, highly centralized grid is already transitioning to solar, wind, and geothermal driven more by unit economics than by environmentalism. Once energy harvesting is sufficiently distributed, the grid itself will dissolve into a distributed foam of local energy transport networks and just-in-time markets.

- 3D-printing is still very much in its infancy, but one day (sooner than you think) it will be possible to 3D-print many of the items in our lives, and certainly most of the small, consumable ones. Global supply chains will be completely disrupted. We will mostly ship raw materials, and we will make finished products near to where they are used. Distributing manufacturing processes to the edges of the supply chain amounts to a form of “reverse-Mercantilism”.

- Mesh networking IOT is not the only use case for mesh networks. Our centralized telecommunications infrastructure is too easy to monitor and manipulate and people will eventually (later than we hope) realize this. A new Internet, built on top of a planet-spanning fully distributed mesh infrastructure both implemented on and incentivized by some future blockchain is inevitable in our view.

Today, you use the Internet to buy products on Amazon which were made in China using raw materials from around the world. The government monitors your Internet traffic. Amazon knows about everything you buy. Huge amounts of dirty energy are wasted transporting raw materials to places such as Shenzhen and then transporting the finished products through a small number of global shipping firms. The cost for all of this inefficiency & overhead is passed on to you. And then you gotta pay that sales tax.

In the future, you will use a mesh Internet to buy blueprints for a product sold in a distributed marketplace to print out in a local 3D-printer and you will pay for the blueprints and the materials & energy the 3D-printer used with cryptocurrency. No one will be able to monitor your messages or transactions. No single company will know about everything you buy. A minimal amount of matter will be transported to you. The energy required to build your product will be sourced sustainably and locally where you live.

When communications, money, manufacturing, and energy are all distributed in this way why would the corporations providing them remain centralized? Global marketplaces such as Amazon can exist on blockchains without requiring corresponding centralized corporations to build them. There may still be large swaths of the economy controlled by global companies but the fabric of these companies will be distributed.

If it sounds laughable to you to imagine that global mega-corporations such as Amazon or Bosch or Merck will dissolve into distributed autonomous organizations (DAOs), consider that Bitcoin already provides a compelling real-world example. Bitcoin is a DAO which “sells” a token (BTC) which serves as a trusted store-of-value for its holders. Bitcoin mining increases the security of the BTC token for its users so Bitcoin miners are “hired” by Bitcoin and paid in the same token. It sounds circular, but it’s really just smartly- balanced incentives.

ICOs, decentralized exchanges, lending, & investment platforms show that many other financial services beyond storing value & making payments can also be provided by DAOs. “World computers” such as Ethereum are trying to distribute computing while other projects are distributing storage, bandwidth, & data. Together these chains will distribute cloud computing, the basis for so much of the modern economy. Though more nascent, there are projects working to distribute identity, social media, journalism, property ownership, insurance, &c. Supply-chain oriented blockchains are trying to disrupt shipping, manufacturing, & logistics.

If global corporations are distributable then why not nation states? Plans for state-backed cryptocurrencies are already operating in several nations. How long before the state itself is backed by a blockchain? After all, blockchains can be thought of as the first political technology in the history of the world and are absolutely capable storing political capital in addition to monetary capital.

It was impossible to predict all the details of our modern world in 1844, and it is just as impossible to predict the details of the future in 2018. But we can certainly see the trend: a more distributed world where energy and resource allocation will still matter, but centralized supply chains, media & energy networks, and the perverse incentives they create will be gone. Blockchains and the distributive technologies discussed above form a mutually self-reinforcing autocatalytic set which will together distribute the world.

So why does it matter?

The Internet was a tremendous innovation, but it was also the endpoint of a centuries-long evolution in centralizing technology. Blockchains are the beginning of a future evolution in distributing technology. Comparing blockchains such as Bitcoin to the telegraph emphasizes the scope of this future evolution and helps you to adopt the long-view on cryptocurrencies.

Amara’s Law applies to blockchains more than any other recent technology:

We tend to overestimate the effect of a technology in the short run and underestimate the effect in the long run. — Roy Amara

If you believe that the ICO token you bought yesterday is going to solve the world’s problems tomorrow (as well as make you arrogantly wealthy), you’re falling for the first part of Amara’s Law. But if you believe that nation states, global supply chains, planet-spanning banks and oil pipelines will not fundamentally change in the next century, you are falling for the second part of Amara’s Law. Blockchains may not fix the world, but they are definitely going to change it.

OK OK, but what does this mean for the Bitcoin price?

However the distributed future looks, Bitcoin is positioned to be its global reserve currency. Bitcoin is flawed but beautiful: we may never use it to buy coffee or as a platform for building web applications, but it has proven to be an excellent way of safeguarding wealth against inflation, censorship, forgery, seizure, and corruption. Emerging “Layer 2” solutions such as the Lightning Network make transacting with Bitcoin even easier. The energy markets, atom exchanges, social networks, global mesh internet, sundry political tribes and, indeed, coffee shops of the distributed future will settle their accounts, eventually, to the Bitcoin blockchain.

Satoshi’s promise was that by holding Bitcoin, you potentially hold a share of the total economic activity of the entire future world. This prophecy galvanized early adopters to buy in, but it is the real work of programmers, entrepreneurs, educators, regulators, and ordinary users that will make this vision come true. If these workers can help Bitcoin survive decades of more FUD, alternating adulation and vilification, solve its own scalability and governance issues, and learn to interoperate with the many other blockchains that are succeeding in their own domains, then the price of a single Bitcoin will be many times what it is today.

If you’re convinced that the major coins such as Bitcoin, Ethereum, &c. are “too big already” and won’t appreciate in price anymore, you’re making the mistake of thinking these technologies & social movements are nearing maturity. They are not. They are still early.

Those of you worried about timing your entrance into Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies, “waiting for the dip”, are similarly making the mistake of chasing an extra 20% return in the short-term at the risk of missing out entirely on future growth.

The truth is, BTC at $5k, $10k, $20k or ETH at $100, $500, $1000 are a bargain. If Bitcoin really is the telegraph then an entire revolution in technology, politics, and society itself is about to occur — and has already started!

So if you believe you’re late to the party, don’t worry — we all just got here. This is a great time to learn about and invest in Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies. Even more important than investing, there’s work to be done! There are technologies to scale, interfaces to build, regulators to educate, intransigent uncles to convince, inefficient industries to disrupt, and new business models to explore. Let’s get started.

Unchained Capital is working on building the distributed future. We are creating financial instruments for long-term Bitcoin holders who believe in cryptocurrency and don’t want to sell their assets but need liquidity.