Security Budget in the Long Run

| If you find WORDS helpful, Bitcoin donations are unnecessary but appreciated. Our goal is to spread and preserve Bitcoin writings for future generations. Read more. | Make a Donation |

Security Budget in the Long Run

By Paul Sztorc

Posted February 14, 2019

A discussion of Bitcoin’s ability to resist 51% attacks (ie, its “security budget”). Competition makes it difficult for one network to collect enough fees – instead, we should try to collect fees from all networks. This post is a somewhat more-empirical sequel to “Two Types of Blockspace Demand”. And to my Building-on-Bitcoin talk.

1. The “Security Budget”

Bitcoin’s “security budget” is the total amount of money we pay to miners (or, if you prefer, the total amount spent on mining – they are the same thing). When this value is low, 51% attacks are cheap. In 2018, BTC’s security budget was about $7 million per day. So, the suppression of BTC (via a never-ending campaign of 51% attacks) would cost –at most– $2.6 billion per year.

$2.6 B is pretty low – by comparison, the 2017 annual US Military Budget was $590 billion, and the FED’s annual operating expenses totaled $5.7 billion.

2. The Block Subsidy

Fortunately, we can expect the block subsidy to give us more security in the future. Even though it “halves” once every four years (effectively falling by a factor of 0.84 per year), it hits for full force no matter how high the BTC exchange rate climbs. As long as annual appreciation 19%+, it fully compensates for the PP lost to the halvening. Historically, the rate has been much higher than 19% (more like 70%+), and so the security budget has increased substantially over time, and will continue to do so for a while.

Of course, eventually the exchange rate must stop appreciating. Even if Bitcoin is outrageously successful, it will apparently reach a point where it simply cannot grow faster than 1.077 per year1, as this is apparently the growth in the nominal value of all the world’s money.

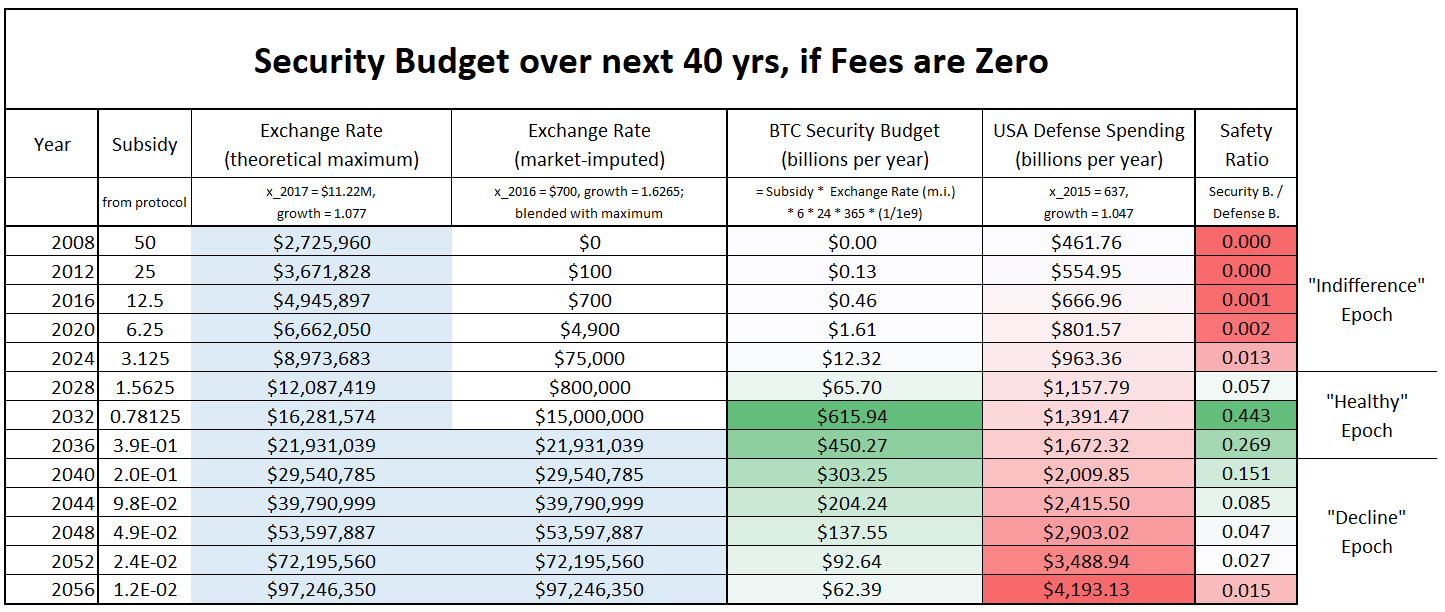

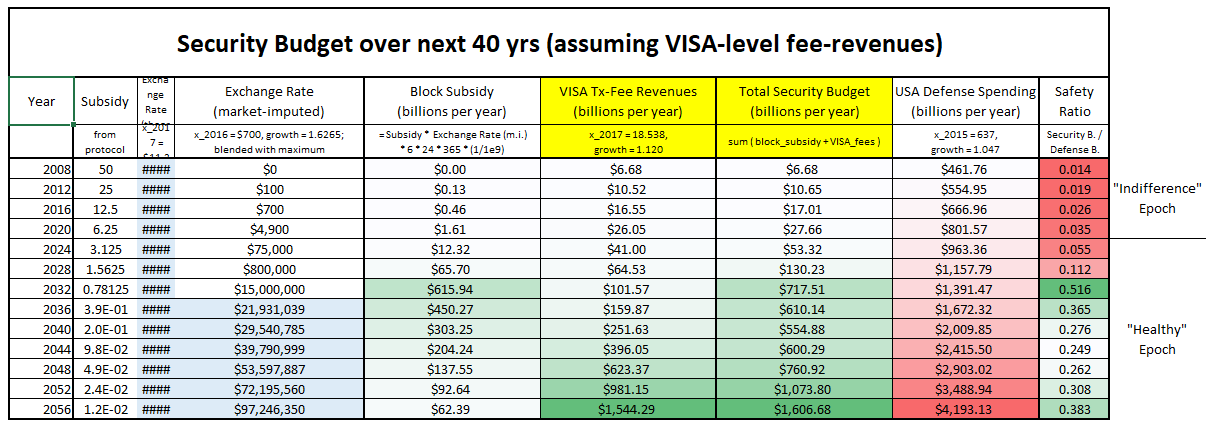

Here I show the growth, and ultimate decline of the security budget:

Above: Bitcoin’s security budget over time.

Above: Bitcoin’s security budget over time.

Each row refers to a different year. Theoretical max exchange rate from the Game and Watch paper. Imputed exchange rate is historical rates and growth factors, with some manual “blending in” so as to more rapidly approach the theoretical maximum. Defense budget extrapolated from wikipedia data. “Safety Ratio” is the percentage of military budget that would be needed to disable Bitcoin. All numbers are in nominal dollars.

The “indifference” epoch is one where Bitcoin is vulnerable, but few adversaries squander their opportunity to attack because they are not paying attention. The “healthy” epoch is one where BTC should be able to deter 51% attacks even from ultra-wealthy motivated adversaries. But the “decline” epoch shows us a bleak future, in which 51% attacks on Bitcoin are easy again.

3. Transaction Fees

i. The Desired “Fee Pressure”

As is commonly known, transaction fees are expected to come to the rescue. As Greg Maxwell remarked:

fee pressure is an intentional part of the system

design and to the best of the current understanding

essential for the system's long term survival

Personally, I'm pulling out the champaign that market

behaviour is indeed producing activity levels that can

pay for security without inflation.

This view, (of a needed “fee pressure”), is common. Roger Ver has compiled similar quotes from other Bitcoin intelligentsia. Roger did this in order to discredit them politically, but the quotes are nonetheless accurate.

ii. The Dual Nature

The dual nature of Bitcoin (as both a money-unit, and a payment-rail) has confused people since Bitcoin was first invented.

In general, monetary theorists and economics ignored the payment-rail (and dismissed Bitcoin as supposedly having “no intrinsic value”). Businessmen and bankers ignored the money-unit (and regarded purchases of BTC as hopelessly naive), and instead tried hopelessly to rip-off the “blockchain technology”.

The confusion persists today in the “scaling debate”, in the form of a discussion over whether or not the “medium of exchange” use-cases are more valuable than the “store of value” use-cases.

And I think it persists in long-run security budget analysis, as well. Consider the following table:

| Revenue Source | Block Subsidy (12.5 BTC) | Transaction Fees |

|---|---|---|

| Market’s Units | …of BTC | …of block space |

| Price Units | … $ (PPP) per BTC | $ (PPP) per byte |

| If BTC price = moon… | …SB Goes Up | …SB Unaffected |

| Meme | Store of Value | Medium of Exchange |

| Slogan | “Digital Gold” | “P2P Electronic Cash” |

While the two are mixed into the same “security budget”, the block subsidy and txn-fees are utterly and completely different. They are as different from each other, as “VISA’s total profits in 2017” are from the “total increase in M2 in 2017”.

VISA’s profits are a function of how cost-effectively VISA provides value to its customers, relative to its competitors (MasterCard, ACH, WesternUnion, etc). Changes in M2 are a function of other things entirely, such as: election outcomes, public opinion, business cycles, and FED decisions. There is some sense in which M2 “competes” with the Japanese Yen, but there are really no senses in which it competes with MasterCard.

iii. Are fees truly paid “in BTC”?

Transaction fees are explicitly priced in BTC. But, unlike the block reward, they do react to changes in the exchange rate. As the exchange rate rises, a given satoshi/byte fee rate becomes more onerous, and people shy away from paying it.

And so tx-fees are not really “priced in BTC”, despite the protocol’s attempt to mislead us into thinking that they are. They are actually priced in purchasing power, which –these days (pre-hyper-bitcoinization)– is best expressed in US Dollars.

So, it is entirely appropriate to say, for example, that “in Dec 2017, BTC had tx-fees as high as twenty-eight dollars “. And it would be inappropriate to say that the tx-fees were “as high as .0015,0000 BTC”. For if the BTC price had been 10x higher2, the tx-fees would have only reached .0001,5000 BTC.

iv. Stimulating Production

Whenever prices rise, entrepreneurs are induced to produce. (Owners are also induced to sell, but we are not interested in that right now.)

The supply of BTC is famously capped at 21 million. The produced supply (aka the “new” supply) is currently capped at 12.5 BTC per block, until the next halving.

The supply of a completely different good, “btc-block-bytes”, is also capped. It was first (in)famously capped at 1 MB per block, and now is capped at something-like 2.3 MB per block.

As was just said: whenever blocks become more valuable, entrepreneurs search for ways to produce more of them.

One way is to reactivate older, marginally unprofitable mining hardware. Production then hastens…temporarily. Of course, after the next difficulty adjustment, block-production will return to its equilibrium rate (of 1 block per 10 minutes).

Alternatively, entrepreneurs can create, and mine, Altcoins.

v. Altcoins as Substitute Goods

Alt-“coins” are very poor substitutes for Bit-“coins”. Each form of money, is necessarily in competition with all other forms: money has strong network effects; the recognizability property has super-linear returns to scale; exchange rates are transaction frictions that are inconvenient; etc. What people wanted was a BTC. They wanted to get rid of all their other forms of money!

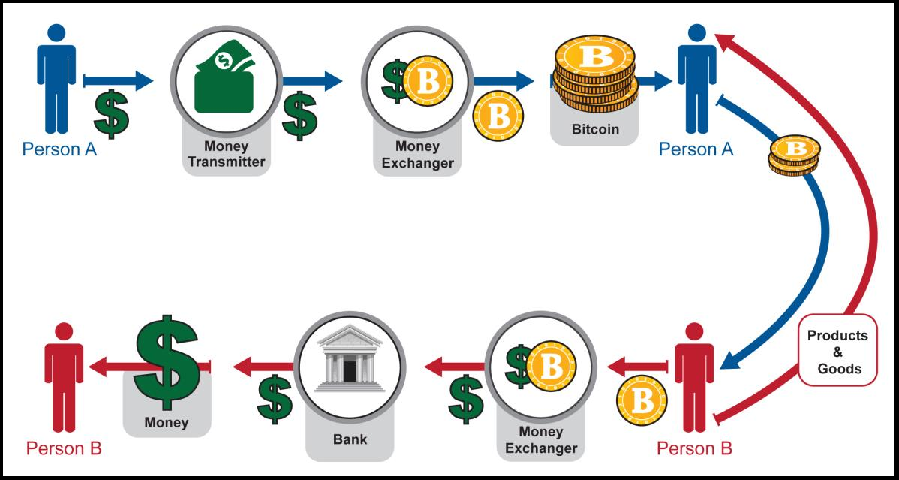

But it is the reverse when we consider transaction fees and “btc-block-bytes”: Altcoin-blockspace is a pretty good substitute for Bitcoin-blockspace. Remember that this type of demand has nothing to do with obtaining BTC. Users merely wish to buy something using the Bitcoin payment-rail. This image from 2013 FINCEN Congressional testimony hopefully makes it clear:

insert caption here

insert caption here

Since the amount of coin sent in a blockchain payment is always configurable, it will always be possible to send someone “twenty dollars” worth of LTC; or “one BTC” worth of DOGE; or “one sandwich” worth of EOS. All of this is made much easier by the “exchangers” (ie: Coinbase, ShapeShift, SideShift, BitPay, LocalBitcoins, multi-currency wallets, CC ATMs, etc) which now take numerous forms and are easy to use.

Furthermore, this (true) premise –that Altcoin-payments are indeed substitutes for Bitcoin-payments– is occasionally explicitly admitted3, even by hardcore maximalists. Especially during the last fee run-up in late 2017:

vi. Competitive Demand for the Payment Rail

The supposedly-essential “fee pressure” has, for the moment, deserted us.

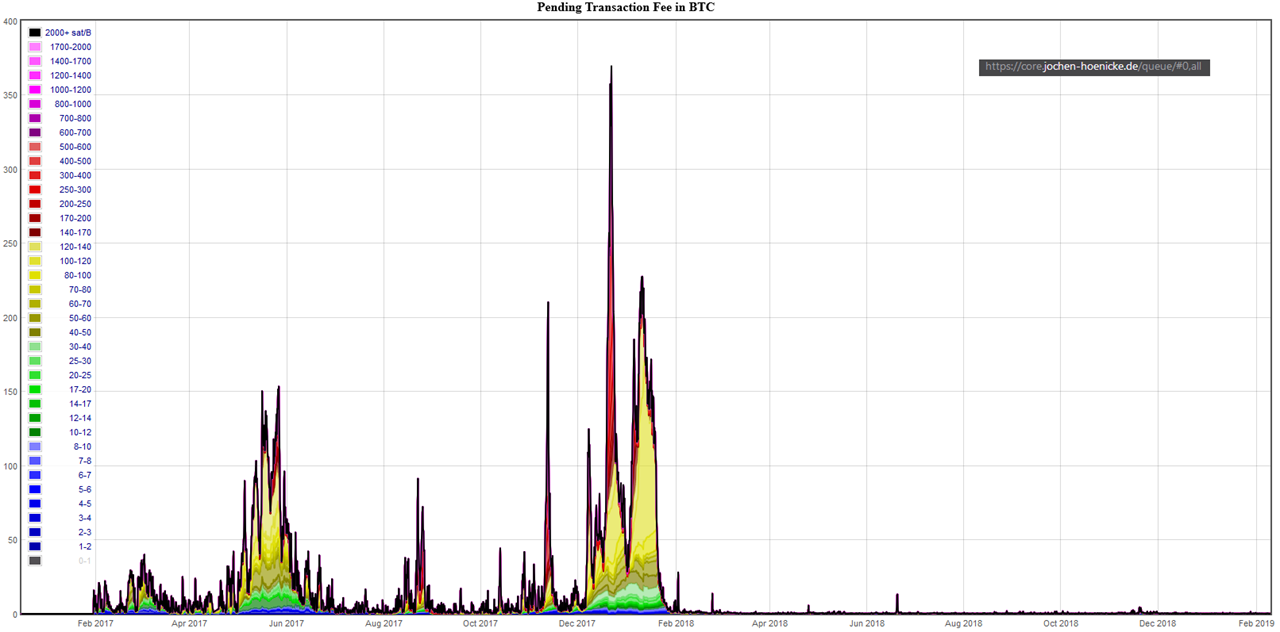

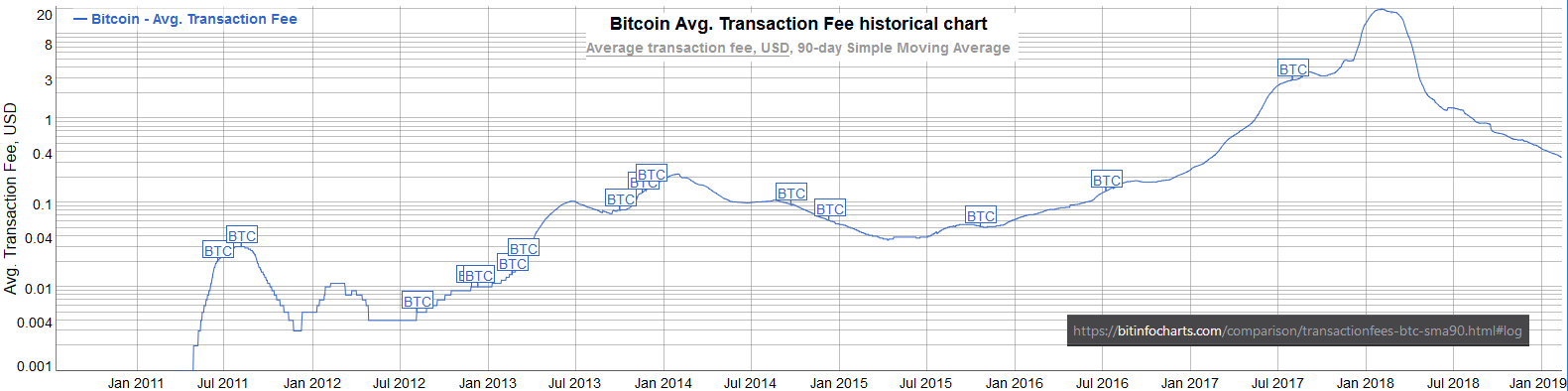

See this graph (from this page) for BTC-priced fees:

insert caption here

insert caption here

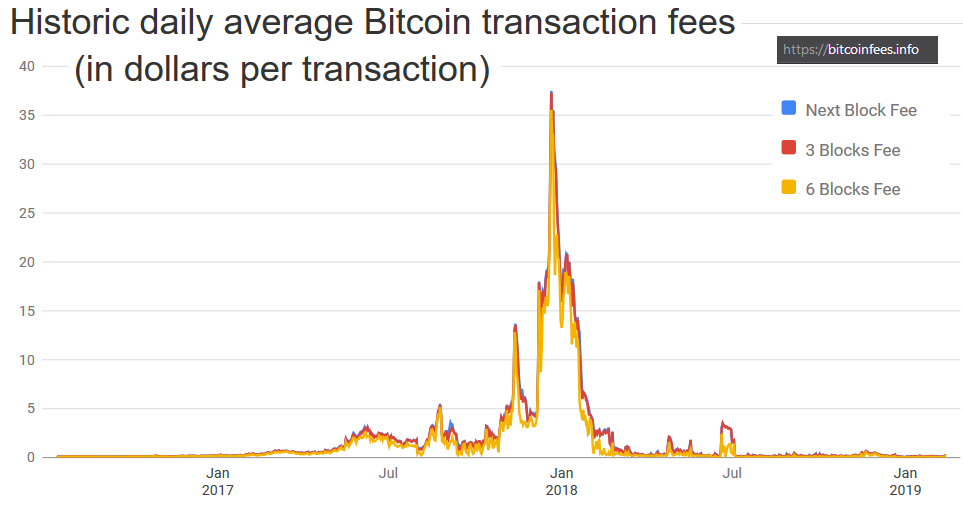

And this graph (from this page) for USD-priced fees:

We see that fee pressure has crumbled. Today, a typical transaction will cost 30-40 cents – much cheaper than a VISA txn.

Compare the historical data, given in 90-day moving-average …

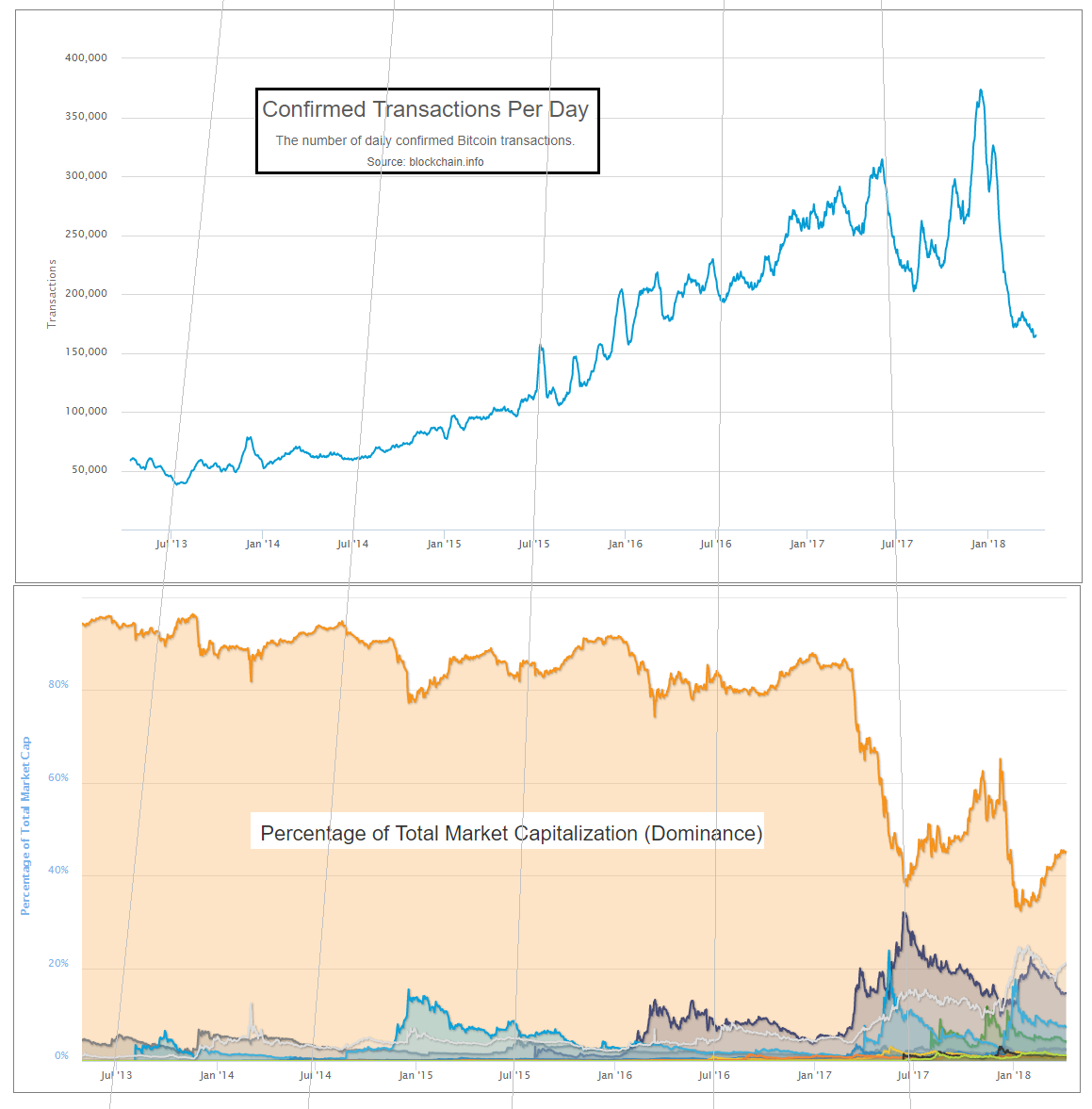

…to the two graphs below:

We see that BTC’s crossing of the “1 USD per transaction line”, in May of 2017, coincides with the rise of Altcoins. We also see that the “pressure” of late 2017 quickly canceled itself out, and then some. Finally, we see that this release-of-pressure coincided with a sudden (and unprecedented) decline in BTC-transactions.

To me, this data refutes the theory that users will pay high BTC fees willingly. In fact, they seem to have only ever paid high fees unwillingly– during a brief “bubble” time (of relative panic and FOMO).

If that theory is indeed false, then total fees will not be any higher –in USD terms– than they are today.

According to blockchain.info, fees in the last 12 months totaled $70 million. (In the 12 months before that, they were $770 million).

Revisit the chart above, and you will see that this barely registers. After all, when $70 M is priced in the units of the chart (billions), it is just $0.07.

If the consumer is cost-conscious, and will only pay the lowest tx-fees, then how can we get those numbers up?

vii. Alternative Fee-Sources

a. Lightning Network

The Lightning Network (if successful) will allow very many “real-life transactions” to be fit into just two on-chain txns.

The immediate effect of this, is to lower on-chain transaction fees; but the ultimate effect is increase them. LN boosts on-chain fees by increasing the utility of each on-chain txn (by allowing each to do the work of many txns), and by therefore making high on-chain fees more tolerable to the end user.

Exactly how much will LN boost fees?

At this point – it is anyone’s guess. But my guess is that they cannot realistically increase by more than two orders of magnitude.

First, on-chain txns are needed to create, and periodically maintain, the LN. So LN-users will still be paying on-chain fees; and will still prefer to minimize these costs. Meanwhile, Altcoins will have their own Lightning Network (they will copy LN, just as they’ve copied everything else). All of these LNs will compete with each other, the same way that different blockchains compete with each other.

Keep in mind, that the fees paid to LN-hubs4 will, by definition, not be paid to miners. So, there is no sense in which LN-fees “accumulate” into one big on-chain txn-fee (in contrast to how the economic effect of each LN-txn does accumulate into a single net on-chain txn).

Second, the LN user-experience will probably always be worse than the on-chain user-experience. LN is interactive, meaning that users must be online, and do something [sign a transaction] in order to receive money. It also means that your LN-counterparties can inconvenience you (for example if they stop replying, or if their computers catch fire) or outright harass you. LN also comes with new risks – the LN-design is very clever at minimizing these risks, but they are still there and will still be annoying to users. Users will prefer not to put up with them. So they will tend to prefer an Altcoin on-chain-txn over a mainchain-LN-txn.

b. Merged Mining Sidechains

Merged-Mined Sidechains do whatever Altcoins can do, but without the need to purchase a new token. So they have infinitely lower exchange rate risk, and are more convenient for users.

On top of that, MM SCs send all txn-fees they collect to Bitcoin miners. Under Blind Merged Mining, they do this without requiring any users or miners to run the sidechain node software.

A set of largeblock sidechains could process very many transactions. In the next section, I will assume that the total Sidechain Network replaces VISA, (and VISA alone), and captures all of its transaction fee revenues. VISA is only a small percentage of the total payments market (which includes checks, WesternUnion, ApplePay, etc), but it is a good first look.

viii. VISA’s Transaction Fee Revenues

Contrary to what I believed just moments before looking this up, VISA does not earn any money off of the interest that it charges its customers.

Observe page 40 of their most recent annual report:

Our operating revenues are primarily generated from

payments volume on Visa products for purchased goods

and services, as well as the number of transactions

processed on our network. We do not earn revenues

from, or bear credit risk with respect to, interest

or fees paid by account holders on Visa products.

Instead VISA’s revenue comes from transaction fees. This perfectly facilitates our comparison.

Total revenues were 18,538 $M in 2017, up from 11,778 $M in 2013. This corresponds to quite an annual growth rate – 12% per year.

If we assume that current trends holds, we get the following:

Above: The ‘security budget table’ from earlier in this post, plus a new column: VISA transaction fees. These fees are added to the base block subsidy amounts, to get a new total security budget.

This security budget does seem to be much safer in the long run, and safer in general.

Conclusion

To deter 51% attacks, Bitcoin needs a high “security budget”. Today’s tx-fee revenues are not high enough; we must ensure that they are “boosted” in the future.

Higher prices (ie, higher satoshi/byte fee-rates) are one way of boosting revenue. Unfortunately, competition from rival chains acts to suppress the market-clearing fee-rate.

A better way, is to attempt to devour the entire payments market, and claim all of its fee revenues. This can be done using Merge Mined Sidechains, without any decentralization loss.

Footnotes

- The math is that 1.077 = (25.94/5.85)^(1/20). And note that 1.077 is below the required “stasis rate” of 1.19. ↩

- I mean that if the USD/BTC price had been 10x higher, throughout the “bubble” of late-2017. In other words, if Bitcoin had started Jan 2017 at around 9,000 USD/BTC and then risen to 190,000 USD/BTC. ↩

- I do remember there being much more of this, but I could only find a few examples (before giving up). Please message me if you can find/remember any other examples. I guess I will eventually remove this paragraph if I never find any more. ↩

- By “fees paid to LN-hubs”, I mean the fees that you would pay, (off chain), to any Lightning Node that your LN-payment routes through. ↩