Lessons from the uneven distribution of capital

| If you find WORDS helpful, Bitcoin donations are unnecessary but appreciated. Our goal is to spread and preserve Bitcoin writings for future generations. Read more. | Make a Donation |

Lessons from the uneven distribution of capital

By Nic Carter

Posted February 8, 2020

What we can learn from distorted maps

As the crypto markets continue their transition from a retail-focused, unrestricted global altcoin casino, to a more constrained and regulated environment, it’s worth zooming out and pondering what long-term allocative outcomes this market is likely to witness. Cryptocurrency purports to allow commerce and capital to flow freely, independent of artificial nation state boundaries. However, when securities are involved, the state tends to intervene.

There is a good reason for this: securities are high-stakes markets governing the allocation of productive capital, and for them to function, the state needs to enforce fairness, disclosure, and information symmetry. In fact, the best example in favor of securities laws I can think of is the anarchy and carnage exhibited in the Initial Coin Offering boom in 2017. If blockchain-lubricated capital markets mature from these early hiccups and some of these equity-like assets become viable, they will surely be indexed to their local jurisdictional rules. To the extent that tokenization and crypto-wrapped securities become investable, I’d venture that the U.S. is strongly positioned to compete for issuers — despite the globalized nature of the crypto industry.

What distorted maps tell us about shareholder rights

It’s often said that the SEC is “pushing innovation abroad” by cracking down on crypto projects, especially those that issue pseudo-equity in the form of a token. This may well be the case. It is also quite a reductive view. Capital clusters in jurisdictions where the rules are understood, where property rights are respected, and where legal systems appropriately apportion power between shareholders and directors. Thus, the enforcement of age-old rules which made the U.S. the most vibrant equity market on earth in a crypto context can be understood as either hostile to issuers, or accommodating to investors. The latter perspective is sorely neglected in the regulatory analysis.

In the issuance of equity, standardization is a godsend. If you work in startups, you will mostly likely have a strong understanding of the nuances of a Delaware C corp or the YC SAFE. When issuers select these instruments to raise capital, they are opting for a set of rules and a legal context which are mutually understood by founders, VCs, and law firms. This often entails cheaper diligence and less legal overhead. Indeed, some VC funds don’t invest in anything other than Delaware C Corps. This is just one anecdote, but it hints at the bigger picture: investors like predictable and comprehensible structures. They like to know where they stand relative to founders, and what their recourse is if something goes wrong. At a global scale, small differences in jurisdictional predictability lead to wildly divergent outcomes.

You may be surprised to learn that the U.S. accounts for 26% of global GDP, but a staggering 40% of global public equity capitalization. This point is best made visually with a chart called a cartogram. What a cartogram does is weight land area by some variable while keeping shape intact (or at least attempting to). Let’s start with a basic map projection. In this case I am using the Plate Carée projection, a variant of the equirectangular projection. This is what it looks like:

World countries shapefile courtesy of ArcGIS Hub (source)

World countries shapefile courtesy of ArcGIS Hub (source)

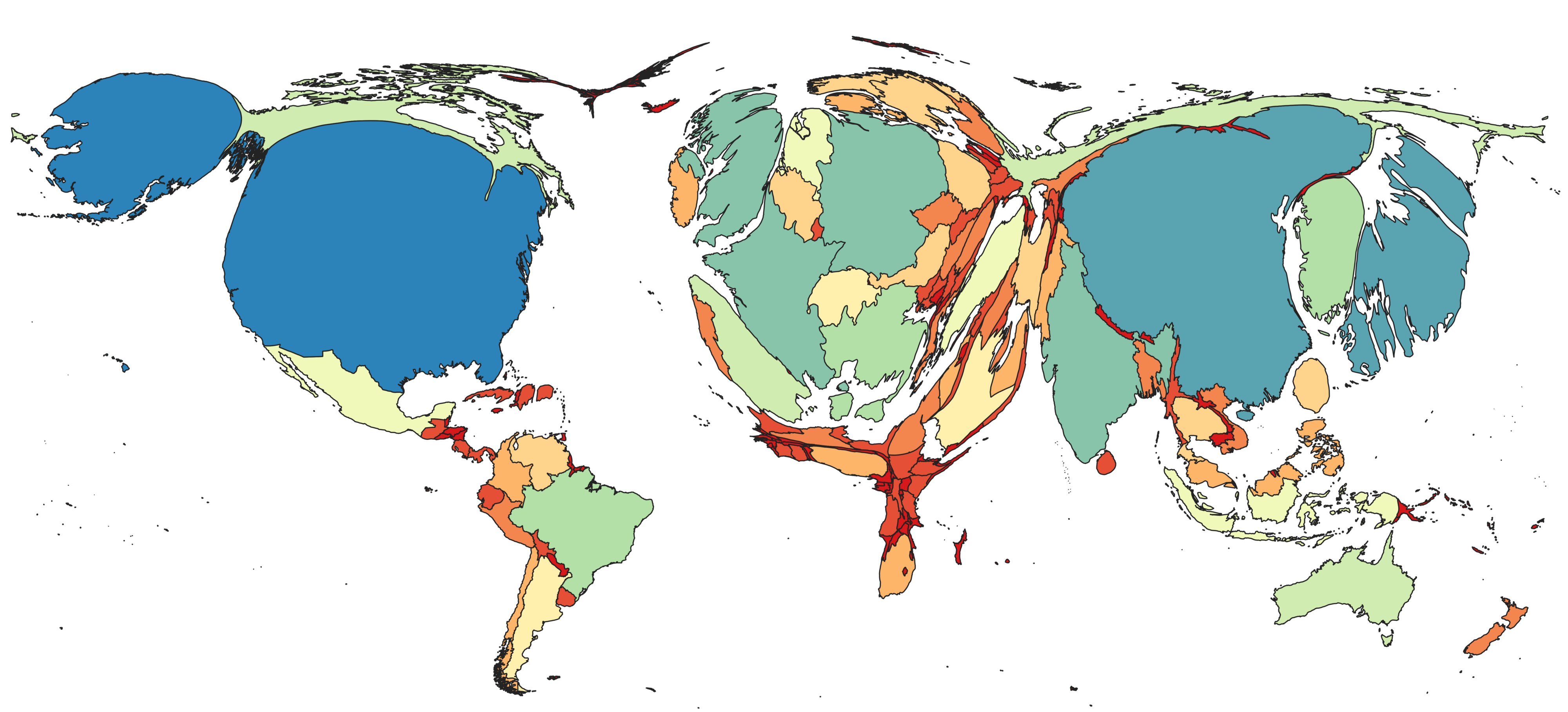

Now let’s weight countries by GDP (2018) so you can get a general sense of the global income distribution. This means that certain more developed countries will swell up and less developed countries will shrink. But I’ll do my best to retain the general shapes of the countries so the map is still intelligible.

Cartogram made with Scapetoad and visualized in QGIS3.4. Data is 2018 GDP in USD terms from the World Bank

Cartogram made with Scapetoad and visualized in QGIS3.4. Data is 2018 GDP in USD terms from the World Bank

I’ve bucketed countries into a few color coded categories so you can compare similar countries by GDP. For instance, with this chart, you can tell that France ($2.5T), Germany ($3.6T), and India ($2.9T) are in a similar range. Same with South Korea ($2T), Brazil ($2T), and Italy ($1.9T). You can also tell that Australia, Spain, Canada, and Russia have similar GDP — between $1.3 and $1.6 trillion. You get the point.

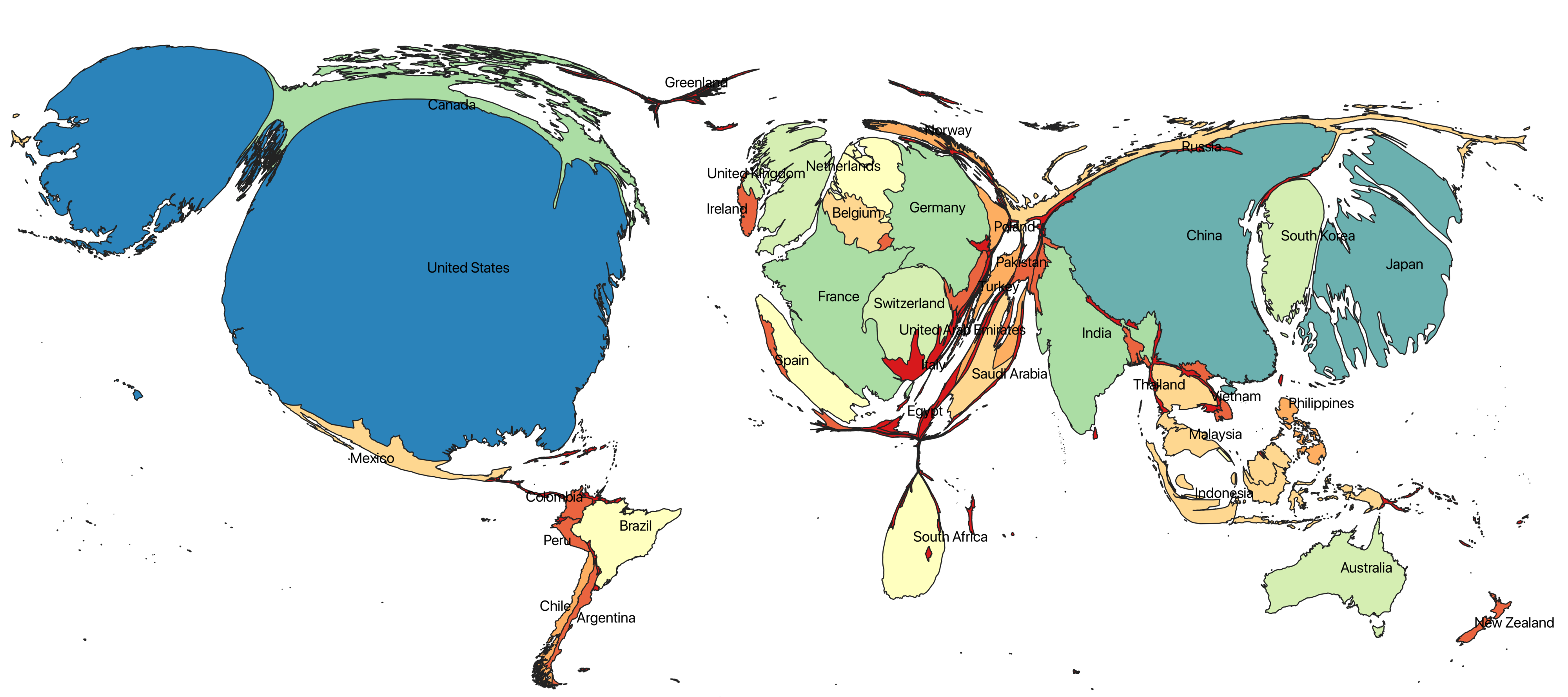

Now if I were to ask you what the same map with domestic public equity capitalization as the key variable might look like, you might imagine it would resemble the above. More GDP, more money to invest in the stock market, after all. Interestingly, this isn’t quite the case. Here’s the map weighted by the size of domestically listed equity markets:

Cartogram weighted by market capitalization of domestically listed companies, 2018 data courtesy of the World Bank

Cartogram weighted by market capitalization of domestically listed companies, 2018 data courtesy of the World Bank

Please note that Hong Kong isn’t present on this map because it sadly wasn’t included in the open source vector file I used to build the country shapes. Hong Kong would be about 50% the size of China on this map. Compare the Public Equity cartogram with the GDP cartogram and you notice a few things immediately:

- the U.S., even though generates a big chunk of global GDP, still punches above its weight in terms of domestically listed equity

- South America and Africa have under-developed capital markets, even relative to GDP

- Chinese equity markets are prominent, but small relative to their share of global GDP

- niche/haven jurisdictions like Hong Kong (not depicted), Luxembourg, Singapore, Switzerland, are overweighted

- Europe represents a significant fraction of equity markets but less than you might expect from their share of global GDP

Let’s dig in to the data a bit more to find the biggest outliers when it comes to countries that punch above their weight from an equity market perspective.

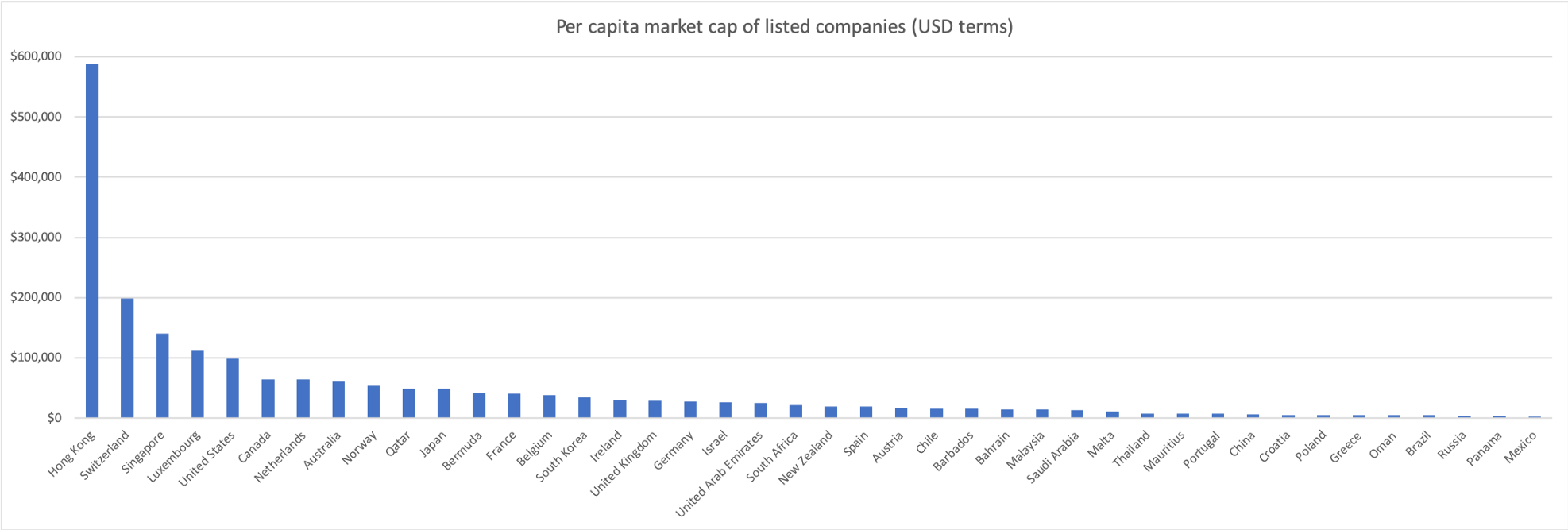

Market capitalization of listed domestic companies (USD) divided by population, World Bank data

Market capitalization of listed domestic companies (USD) divided by population, World Bank data

Amazingly, the per capita market cap of domestic equity in Hong Kong is US$588k. This is a bit of an exception, as many Chinese companies choose to list on the HKEX rather than in Shanghai or Shenzhen. This is partially a function of less onerous listing requirements in Hong Kong, partly a function of Hong Kong’s financial hub status, and tighter relationships with western capital markets, and partially a function of the fact that Hong Kong’s legislature, judiciary, and attitude towards property rights are influenced by its former status as a British colony.

For a more detailed take on why Chinese firms are so fond of listing in Hong Kong, Fanpeng Meng’s A History of Chinese Companies Listing in Hong Kong and Its Implications for the Futureprovides additional context:

Specifically, there are some fundamental elements [present in Hong Kong]: a stable and sound legal system with strong respect of private property ownership, an absence of exchange rate control with the linked exchange rate, an efficient and sophisticated banking sector populated by some of the world’s top banks, a simple and low-rate taxation regime in which there are no capital gains taxes and whereby income taxes are charged on a territoriality basis, and a relatively clean and transparent business environment intensively monitored by the government.

Listings in Hong Kong are quite significant relative to China, totaling about US$4.3T compared with China’s US$8.7T.

Other states scoring highly on the per capita equity market cap figures include a smattering of haven states like Switzerland, Singapore, Bermuda, and Luxembourg, and developed nations like the U.S., Canada, the Netherlands, Norway, and Japan. Regional financial hubs like Qatar, the UAE, and South Africa also score well by this measure.

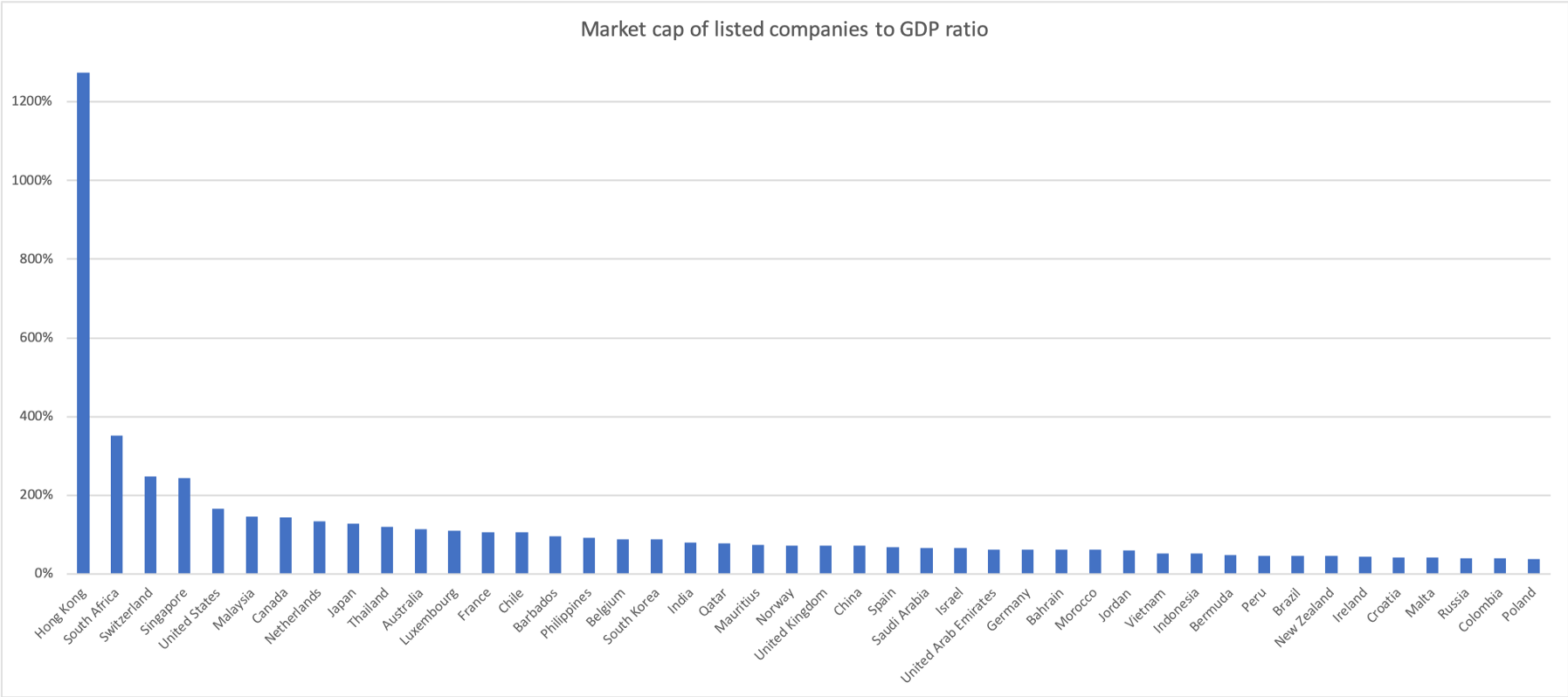

Another similar measure is the aggregate market cap to GDP ratio. This synthesizes the two cartograms depicted above, so you can find the biggest outliers without having to visually inspect the charts.

The ratio of the market capitalization of listed domestic companies (USD) to 2018 GDP, World Bank data

The ratio of the market capitalization of listed domestic companies (USD) to 2018 GDP, World Bank data

Compared with the per-capita metric, this one better selects for nations which have a lower overall standard of development but still have large equity markets relative to their economies. Again, Hong Kong is the stark outlier here. But it’s joined in the list of unexpectedly large equity markets by places like South Africa, Malaysia, Thailand, and Chile.

South Africa is an interesting case study. In Africa, there are only three meaningfully developed local equity markets — Nigeria, South Africa, and Egypt. South Africa, a historically prosperous former British colony with the lingering presence of British institutions, is the largest of the three. Literature on equity development in Sub-Saharan Africa is sparse.

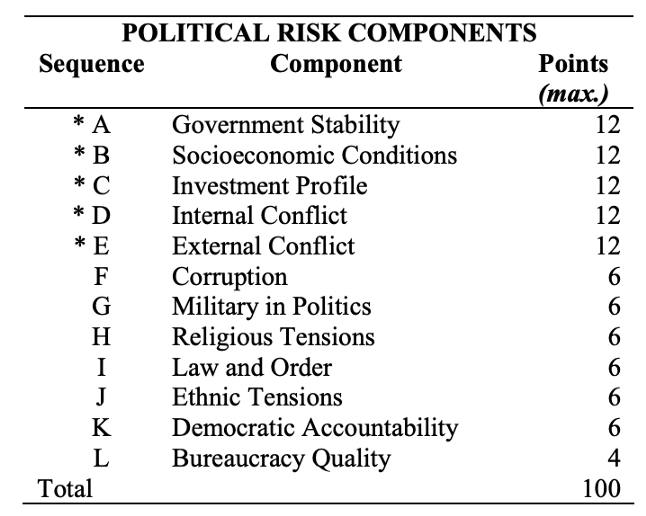

Political risk determinants from the International Country Risk Guide Methodology

Political risk determinants from the International Country Risk Guide Methodology

Some answers can be found in an IMF working paper on the topic (Andrianaivo and Yartey 2009). The authors conclude from a cross sectional regression that the most important determinant of equity market development in Africa, aside from straightforward variables like domestic savings and per capita GDP, is political risk. This stands to reason: if a military junta takes over, or parliament is dissolved, or the country experiences armed insurrection, equity markets will not develop. I’ve inserted the political risk rubric that the authors used to give you an idea of the relevant criteria. Historically, South Africa has been relatively conflict free (their main post-independence conflicts were minor excursions in Namibia and Angola) and has benefited from stable rule under the ANC, although political conditions have deteriorated in recent years.

My main reaction from the data is to observe that the development of a vibrant equity market is somewhat of an aberration. There are a huge number of disqualifying features — and indeed, your typical state does not in fact have a liquid domestic equity market. So what explains the uneven development of public equity markets around the world?

Rules Make the Market

So why do some jurisdictions dominate when it comes to the issuance of public equity? As it turns out, there’s an incredibly vibrant literature motivated by this specific question. The foundational, field-defining paper is Law and Finance by La Porta, Lopez-de-Silane, Shleifer, and Vishny.

If you haven’t read it, I strongly recommend a read. It’s one of my favorite economics papers, because the methodology really is dead simple: the authors simply look at the variance in investor protections across a broad array of countries, and realize that legal traditions in those countries explain a significant fraction of that variance. In other words, the legal tradition employed on a country-by-country basis, which informs_ what it means to be a shareholder._

Specifically, the authors divide commercial legal traditions in 49 jurisdictions into civil law and common law, further subdividing civil law into German, French, and Scandinavian variants. Common law refers to the British tradition of allowing judges to shape the law through precedent, whereas in civil law, inherited from the Roman tradition, the law is generally created by the legislature, with case law (precedent-setting through court cases) being secondary.

As the authors (henceforth LLSV) note,

[Civil law] originates in Roman law, uses statutes and comprehensive codes as a primary means of ordering legal material, and relies heavily on legal scholars to ascertain and formulate its rules

More abstractly, you can think of common law as a bottom-up, adaptive approach, and civil law as a top-down, more rigid approach. The consequential differences between jurisdictions with diverging legal traditions are significant; indeed, it has been compellingly argued that Brexit primarily boils down to a dispute between legal traditions (in which the EU attempted to impose a civil law tradition on the common law UK, causing frictions). In the words of the Economist, “English lawyers take pride in the flexibility of their [common law] system, because it can quickly adapt to circumstance without the need for Parliament to enact legislation.” In short, common law is considered to be faster moving and more adaptable — ideal for fast-changing capital markets.

A full 21 countries in the sample inherit France’s civil law tradition, many of which were conquered by Napoleon. Others were added as part of France’s colonial holdings in Africa and the Pacific. And French jurisprudence informed the structure of post-colonial regimes in the wake of Spanish and Portuguese empires in Latin America.

The British Empire led to the proliferation of English jurisprudence throughout the commonwealth. Strikingly, these colonial origins seem to have had long term effects on the future development of shareholder rights, hundreds of years later. As LLSV note:

[L]aws differ a great deal across countries: an investor in France has very different legal rights than she does in Britain or Taiwan. Moreover, a large part of this variation is accounted for by differences in legal origin. Civil laws give investors weaker legal rights than common laws do. The most striking difference is between common law countries, which give both shareholders and creditors the — relatively speaking — strongest protections, and French civil law countries, which protect investors the least.

Mechanically, LLSV enumerate specific shareholder rights which speak to the extent to which shareholders are protected against directors. A selection are listed below:

- One share one vote: whether laws exist to tie shares to votes, as opposed to dual classes or nonvoting tranches of equity. The authors consider jurisdictions with these laws as more shareholder friendly

- Proxy by mail: whether or not shareholders are allowed to vote by mail (more hindrance in shareholder votes disempowers shareholders, especially smaller ones)

- Oppressed minorities mechanism: whether or not minority shareholders (owning 10% or less of share capital) have the ability to challenge the decisions of management or force a buyout of their shares in the case of certain changes like M&A activity

- Preemptive rights: whether shareholders have the right of first refusal over new equity issuance

- Percent of capital required to call a shareholder’s meeting: the higher the required fraction, the less friendly the jurisdiction is to minority shareholders

Their conclusions, while simple from a statistical perspective, were revelatory in the corporate governance literature. LLSV found that:

[A]long a variety of dimensions, common-law countries afford the best legal protections to shareholders. They most frequently (39 percent) allow shareholders to vote by mail, they never block shares for shareholder meetings, they have the highest (94 percent) incidence of laws protecting oppressed minorities, and they generally require relatively little share capital (9 percent) to call an extraordinary shareholder meeting. The only dimension on which common-law countries are not especially protective is the preemptive right to new share issues (44 percent). Still, the common-law countries have the highest average antidirector rights score (4.00) of all legal families. Many of the differences between common-law and civil-law countries are statistically significant. In short, relative to the rest of the world, common-law countries have a package of laws most protective of shareholders.

Taking the analysis further, the same four authors followed their seminal paper with the 1997 Legal Determinants of External Finance, demonstrating that not only do common law countries systematically offer better shareholder protections, but that these investor protections empirically manifest in larger and more robust capital markets.

The authors summarize the key finding:

[T]he legal environment — as described by both legal rules and their enforcement — matters for the size and extent of a country’s capital markets. Because a good legal environment protects the potential financiers against expropriation by entrepreneurs, it raises their willingness to surrender funds in exchange for securities, and hence expands the scope of capital markets.

This might seem like a simple point — more investor assurances yield more capital deployed, but when you reflect on the fact that these assurances trace back to the legal philosophy undergirding the financial system, one becomes starkly aware of the path dependence in capital market outcomes. Put simply: institutional quality dictates allocative outcomes. The U.S. isn’t just the largest hub of capital formation on earth, it’s disproportionately large. This system creates extreme outliers like Hong Kong, Singapore, or Luxembourg.

A related conclusion can be found in Hernando de Soto’s book, The Mystery of Capital. De Soto evaluates the relationship between property rights and capitalism in a large number of countries worldwide, and concludes that for capitalism to function properly, it must rest atop the bedrock of strongly codified property rights. His reasoning is as follows: the main form of savings for individuals worldwide is through property (in particular, real estate). The main way that capital formation occurs on a small scale is through the monetization of that property, turning it from a purely instrumental asset (somewhere to live) into a capital asset. One example of this would be an individual borrowing against their house in order to set up a small business. If lots of savers can mobilize the capital that they naturally accumulate, capitalism can flourish.

However, as de Soto finds, a significant chunk of property, especially in the developing world, is poorly codified. That is to say, homeowners cannot prove that they hold the deed to their home (a deed may not exist), and they may not have a plausible path to formalizing their ownership. This inhibits their ability to monetize their property at all. Typically, this is due to a dysfunctional bureaucracy or a state apparatus which does not provide a means for incorporating black/grey markets into the formal economy. My takeaway from this remarkable book is that free market economies alone are not enough; they must be accompanied by a legal and bureaucratic apparatus which is flexible enough to enable property owners to make transition from de facto to de jure, and these rights must be consistently respected. For a longer take on De Soto’s conclusions as applied to Bitcoin, see Allen Farrington’s essay on the topic.

Cryptocurrencies, perhaps more so than any asset, mitigate these institutional constraints. It’s trivial to prove to a third party that you own some Bitcoin; it’s trivial to self-custody this claim, and settlement is physical and almost immediately final. Cryptocurrencies are monetary institutions — the protocol lays out a set of rules for permitted behavior, and all participants must adhere to them. This is what gives cryptocurrencies such remarkable global penetration: users mutually understand where they stand relative to the system and the established ruleset, and trust that no well-connected lobbyists are able to exert local policy on system. This is what Nick Szabo refers to as social scalability — the idea that a system can only scale to serve millions of disparate users if it standardizes behavior in a narrow domain (say, rules for what transactions are valid) while minimizing idiosyncrasy and obscurity (which undermine the system’s credibility).

Don’t Count the U.S. Out

Within the crypto industry, the U.S. has a reputation for being extremely restrictive with regards to the issuance of new cryptoassets. Since 2017 with the infamous DAO report, the SEC has made it quite clear that ICOs are more often than not unregistered securities issuances, and that issuers should be held to the same standard as conventional issuers of securities. In the U.S., if you want to sell equity to the general public, this entails significant legal costs and a high standard of transparency.

In the crypto markets so far, virtually no issuers have met this conventional standard (one exception is Blockstack). Moreover, it’s not even clear what information would be considered material for the issuance of a novel protocol or token. In their paper _What Should Be Disclosed in an Initial Coin Offering?, _Brummer, Kiviat, and Massari convincingly make the case that the various disclosure frameworks in the U.S. poorly fit the reality of token issuance, calling for a more appropriate model to be devised.

The significant amount of teeth-gnashing within the crypto industry belies the reality of these markets: the vast majority of tokens sold to the public were entirely meritless, and carried no investor protections whatsoever. Even in cases where tokens purportedly held benefits relative to conventional issuance, with touted features like algorithmically enforced vesting schedules, much of the time these soft provisions were not actually enforced. Hoffman’s _Regulating Initial Coin Offerings _takes a careful look at the promises made by promoters which could have been algorithmically enforced. In a survey of the top 50 ICOs that raised significant capital in 2017, Hoffman evaluates the actual implementation in code of promises made to investors. These fall into three categories:

- Promises made about the restriction of supply

- Promises made about vesting schedules that team members were subject to and restrictions on transfers

- Promises about surrendering power to modify smart contracts once deployed (many issuers claimed they would ultimately give up this power)

Unsurprisingly, the authors, by examining the actual code written by issuers, find overwhelming noncompliance with these relatively weak restrictions. So not only were issuers providing extremely limited assurances to buyers; those issuers could not even adhere to their own, self-imposed standards!

So we have a situation where the vast, vast majority of token offerings openly flouted the law. And _lex cryptographia _was an inferior substitute for the law: the few assurances which could indeed be encoded into a smart contract were only spottily upheld. In this context, U.S. policy towards token issuance seems downright reasonable. Assuming that the predominant legal analysis of token launches (in which a single issuer sells tokens to the public) as unregistered securities is correct, the fact that this issuance was happening through a new technological medium is irrelevant.

If you strip away the technobabble and the (generally spurious) claims of “decentralization” and “unstoppable applications,” you are left with the straightforward issuance of pseudo-equity to the general public. That anyone, even the most devoted crypto stalwarts, imagined securities regulators would turn a blind eye to this practice in perpetuity is baffling. And gradually, the SEC has come to reckon with this market niche. By being relatively (but not overly) stern, U.S. regulators are positioning themselves for a middle path. Far from outright banning tokens and the industry surrounding them, regulators have meted out a mixture of punishments. The SEC has prosecuted the very worst ICOs and given amnesty to others. Some academics have even praised the much-maligned SEC strategy of selectively enforcing the law.

Reminding ourselves that the U.S. has a 40% share of public equity markets for a reason, the professed strategy of many industry participants to seek greener pastures elsewhere seems short-sighted. The fact that an inferior instrument (the public ICO) did not get a regulatory blessing does not mean that the U.S. is destined to lose its crown as the premier locale for capital formation. Indeed, many high profile securities regulators in other capital-friendly jurisdictions are falling into step with the U.S., as is customary. If crypto issuance is to evolve into something friendlier to buyers, with functional, germane disclosures, genuine algorithmically-enforced vesting and lockups, and perhaps other strongly codified investor protections, there’s no reason that regulators wouldn’t acknowledge this reality. That they haven’t given carte blanche to these issuances is a reflection on the poverty of the implementations we’ve seen so far, not the weakness of the idea.

Recall, given the above, why the U.S. hosts a disproportionate share of public equity capital. Not only has the U.S. been a hegemonic power for most of the last century, but it has been politically stable, has not seen violent conflicts on its shores, and it boasts an accommodating common law regime which has manifested in strong shareholder protections. Additionally, it has a large middle class for which investing in equities is as much as pastime as it is a necessity. This affinity for active consumer participation in capital markets has unsurprisingly spilled over into crypto as well. Coinbase, the largest crypto exchange/custodian in the world (by far!), is an American company. The largest financialized Bitcoin product is the Bitcoin Investment Trust, issued by the NY-based Grayscale. The first established global financial institution to take Bitcoin and digital assets seriously was the Boston-based Fidelity. To the extent that this industry is an asset class (to be clear, the jury is still out on this!)_, _jurisdictions with the financial plumbing and the consumer demand for exposure will naturally be the first to service it.

This perspective may strike you as anglocentric. However, consider it in context. Within the crypto industry, the U.S. is considered a pariah simply for enforcing its local laws (and even then, extremely permissively — see the Block.one settlement). The token frenzy has been chased overseas for now, but it’s unlikely to develop into a functional securities market if it operates in an anarchic mode, dependent on the goodwill of marginal jurisdictions. The industry’s best hope is to acknowledge that market oversight is what makes them function and embrace a regime which takes a commonsense view about shareholder/tokenholder protection.

When and if these markets do mature, and security tokens, or on-chain cashflow-wrapped instruments, or highly automated smart-contract-mediated equity do emerge as a meaningful segment of the securities industry, I would fully expect U.S. regulators to engage productively. At that time, issuers and market participants will benefit from taking part in the most dynamic capital markets on earth.