Is Bitcoin Compatible with Banking?

| If you find WORDS helpful, Bitcoin donations are unnecessary but appreciated. Our goal is to spread and preserve Bitcoin writings for future generations. Read more. | Make a Donation |

Is Bitcoin Compatible with Banking?

Yes, but banking must be disintegrated

By Zane Pocock

Posted April 23, 2020

Photo by Jason Pofahl on Unsplash

Photo by Jason Pofahl on Unsplash

In the past, banking served two distinct functions, typically operated by separate businesses: warehousing wealth and facilitating loans.

These services are immensely valuable and typically harmless on their own. But it was an integration of banking functions that ultimately cemented the normalization of today’s fractional reserve banking system, allowing for market distortions that gave rise to precarious debt-fuelled bubbles like the one we’re watching unfold right now. It thus incentivized a structural fragility that placed commercial banking in a position of outsized importance to the functioning of society. Banking used to be about providing services to the free market, not the centrepiece.

The instrument that was manipulated to conflate these two banking functions was commodity money — a cumbersome monetary technology that was inevitably centralized, captured and manipulated to the point that paper claims on it were no longer redeemable.

With its absolute scarcity, Bitcoin is positioned in stark opposition to the monetary and banking status quo, and can serve as the medium for a philosophical and practical resurgence against the fiat monetary paradigm. Further, it is designed with explicit provisions that can be programmatically harnessed to keep banking roles separate once again.

While I argue that the Bitcoin communication protocol should explicitly not be defined as “money” in the legal sense, its scarce information space has accrued value such that those who exercise control over some of it have inevitably sought solutions for its security and leverage (warehousing and loans). By understanding the history of traditional banking institutions and the unique features offered by Bitcoin, participants in the Bitcoin network can acknowledge the value offered by these services whilst being careful to harness Bitcoin’s assurances to continue separating these roles.

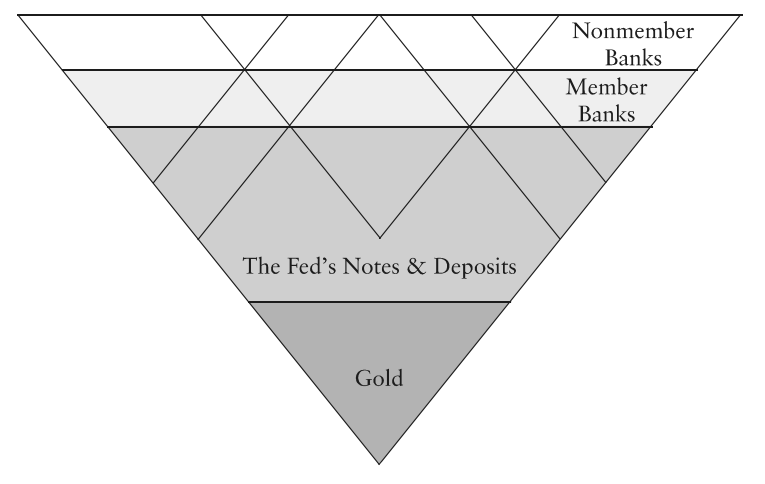

A Brief History of Banking

In his great treatise on money and money substitutes, Theory of Money and Credit, Mises demonstrated that fractional-reserve banking was the root cause of the business cycle, arguing that the issuance of uncovered money titles reduced the interest rate in the credit market below its natural level. If, for every dollar of silver held at a bank, the bank had issued two dollar bills with legal title to the one underlying silver dollar, then the circulating supply of money would have doubled. The law of diminishing marginal utility dictates a reduction in the relative demand for the new money and thus reduces the price that can be demanded for access to it (interest rates). Thus, businesses are likely to borrow beyond what they should (it’s cheap to do so), ultimately becoming overleveraged and misallocating resources before a market downturn corrects these inefficiencies.

How money substitutes are inflated from an underlying asset (fractional reserves). Source

How money substitutes are inflated from an underlying asset (fractional reserves). Source

Mises’ student, Murray Rothbard, made the mechanics of this lesson more accessible to the layperson in his book The Mystery of Banking. Rothbard argued that it was thanks to the confluence of two distinct forms of banking that a fractional reserve banking system was able to flourish, ultimately creating the fiat paradigm we live under today. These distinct banking functions were those of deposit and loan banking.

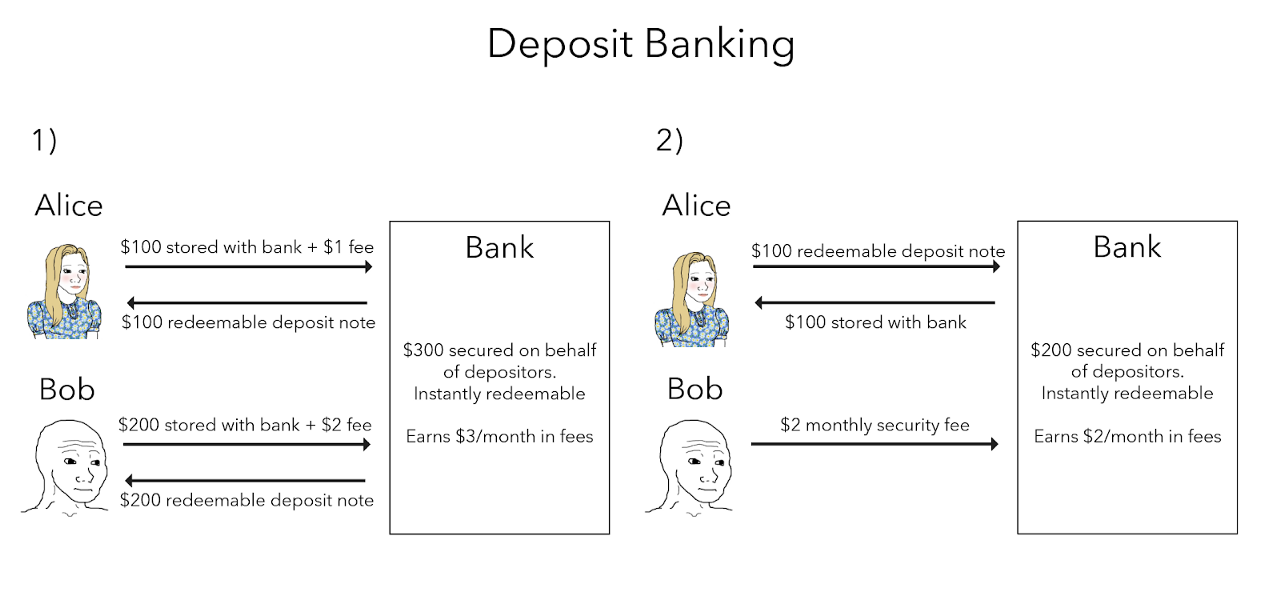

A money warehousing business (a deposit bank) would offer centralized security services to safeguard monies in exchange for a fee paid by the customer. With commodity monies, the returns to violence are high — it makes economic sense for savers to employ a service responsible for defending against theft or loss. These commodity monies also suffer from inconveniences in divisibility and transportability, so another role of the deposit bank was to provide money substitutes (bank notes) that could be carried and exchanged more freely between participants in the economy, with those notes directly convertible to the real money (such as gold) held on deposit at a moment’s notice.

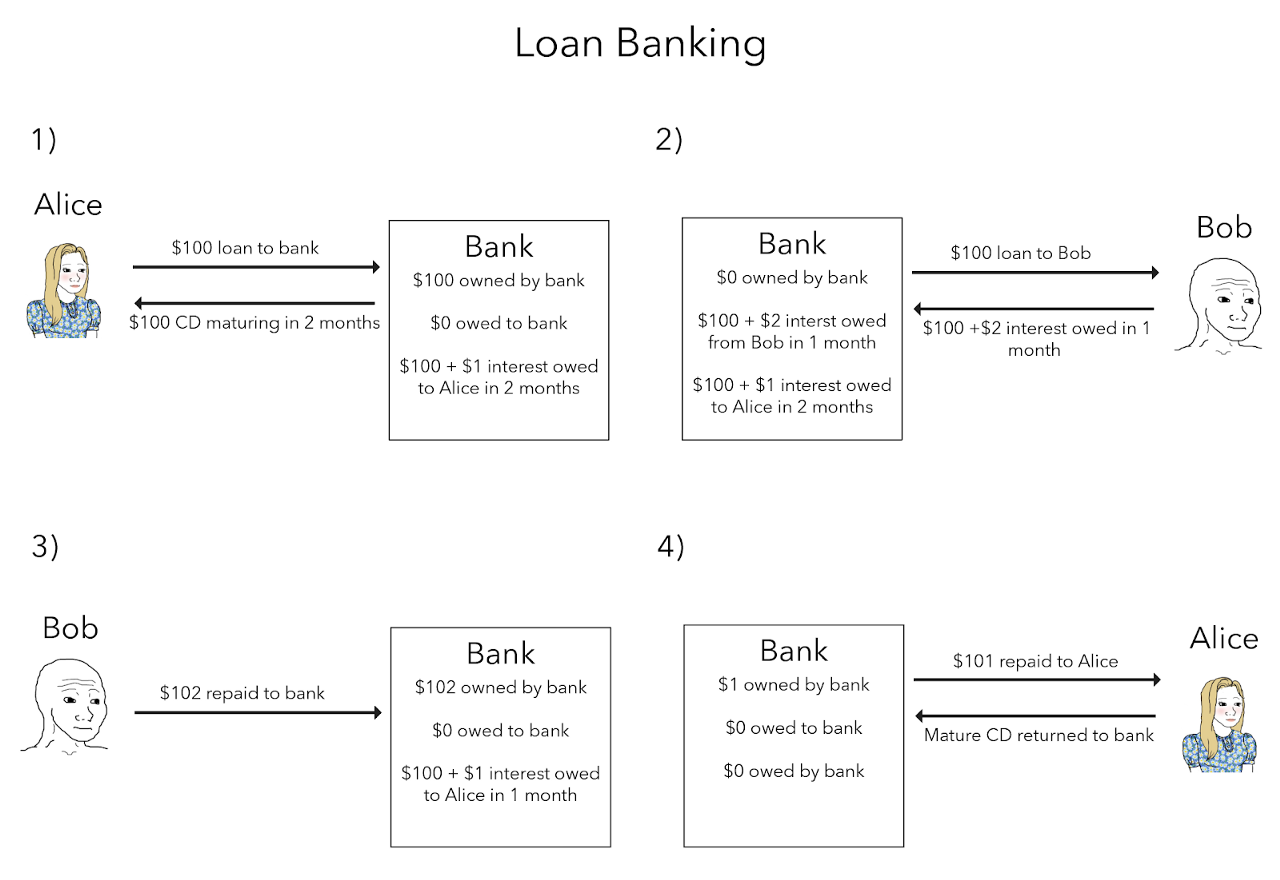

Separately, credit banking businesses, such as those observed in Venice in the Middle Ages and the Scriveners of 17th C England, might explicitly borrow money from depositors and pay them in the form of interest for the privilege and risk. These certificates of deposit would identify a fixed term; at maturity, funds would be returned to the creditor with an interest payment for taking on the default risk of loaning to the bank. The bank would make money by then lending these funds to other businesses and individuals, say for mortgages, charging a higher interest rate than they were paying to the initial client and pocketing the spread. Risk officers for the credit institute would ensure their debts reached maturity after the money they loaned out was repaid, thus remaining solvent.

Rothbard’s insight was to acknowledge that both forms of banking businesses would fail occasionally, but that this was a good thing. Bank runs on deposit banks running fractional reserves would hurt defrauded depositors, for the institutions were effectively operating whilst insolvent. But such failures encourage greater due diligence and maintain the money supply in the long run by weeding these institutions out of the economy. Meanwhile, loan banking is explicit in its risks: there is a palpable chance that a credit institute might default if it mismanages its risk exposure. In simple terms, interest rates are the market rate for 1) buying current access to monetary instruments (the time-value of money) and 2) pricing their default risk.

Rothbard posits that a marriage between the two banking functions put an end to this age and was critical to today’s self-reinforcing cycle of fractional reserve banking, monetary inflation and central banking. He illustrates that central banks lifted the restraints on fractional reserve banking by putting a floor under the whole system that ultimately allowed for excessive credit expansion (printing money) before finally severing any relationship to an underlying asset at all (fiat money).

Legal paradigms

Another great work of economic literature was written on this issue more recently. Where Mises and Rothbard arrived at a discussion of banking by first analyzing how money comes to be used, Money, Bank Credit and Economic Cycles by Jesús Huerta de Soto starts with the two forms of banking before going on to derive the economic and legal implications of such a system.

Irregular deposits

De Soto argues that deposit banks dealing in fungible goods like commodity monies were dealing in irregular deposits, meaning that the same precise gold bar didn’t need to be returned to the depositor. Legal ownership of the specific gold bar was transferred to the bank on the proviso that gold of the same quality and quantity was available instantly to the depositor (ipso facto requiring 100% reserves) — the certificate of deposit was a fully covered money title.

What makes this important for the present discussion is by contrasting it with regular deposits, such as custody of an artwork. Irregular deposits technically transfer legal ownership of the gold to the bank while requiring that it remains fully covered, whereas custody of an artwork clearly doesn’t involve the transfer of ownership. This created a paradigm where the bank was held responsible even for an “act of God”. Thus the bank acted not only as a safekeeper, but the debt they owed to a depositor was so senior that the institutions came to serve as a form of insurance. This would be a moot point for custodying something non-fungible; a destroyed painting can clearly not be returned to the rightful owner.

If the institution is responsible even for black swan events, then the flaw in any form of fractional reserves is obvious: de Soto compellingly summarizes that “if the depositary has acted fraudulently and has employed the deposited good for his own personal use, he has committed the offense of misappropriation.” Thus, if an institution serving a warehousing role at any point does not have 100% reserves, it is comparable to a painting loaned to a gallery being sold by that gallery. The legal paradigm upholding this intuition existed until surprisingly recently: de Soto draws our attention to a decision by the Court of Paris in 1934 that convicted a banker for violating the expectation of 100% reserves.

Unfortunately, this rich history and legal precedent has been rendered trivial for now. The technical transfer of ownership involved in irregular deposits allowed for a dishonest play on definitions, with arguments successfully being made by legal counsel that conflated credit contracts (loans) and deposit contracts (warehousing) as essentially the same thing. These functions of banking are now joined at the hip.

Bailment

If uncovered money titles are the root cause of the business cycle, fraudulent, and enabled by contemporary banking structures, then in Bitcoin it will pay to strictly adhere to a different framework. Fortunately, the “not your keys, not your bitcoin” meme has lent prominence to a particular legal relationship for assets held under custody: bailment.

When an art collector lends a painting to a gallery, that painting is still the collector’s property. It doesn’t matter that the owner doesn’t currently exert possession or physical control over it. This is called bailment: when physical possession and control are handed to a third party, but the original owner retains legal title.

As Caitlin Long has been fighting for in Wyoming, legal recognition of a bailment relationship between depositors and a Bitcoin custodian is likely to be an important line of defense for those who need to employ the services of a custodian. Importantly, in a bailment relationship the asset never touches the custodian’s balance sheet, meaning a properly-written contract will ensure that rehypothecation is not legally possible in this scenario (where the custodian uses deposited assets as collateral against their own business loans). By extension, liens ought not be placed on collateral by the business’ debtors (where another party engaged by the custodian, such as an investor, might attest to seniority over assets under custody in a liquidation event).

Bitcoin Fixes This

Aside from correcting legal definitions, the Bitcoin protocol offers certain assurances that deserve far greater attention in conversations about its custody. Most importantly, if parallels between Bitcoin services and banking are to be found, it should be observed that Bitcoin natively offers tools that can be employed to explicitly delineate between custody and loans.

Bitcoin is a communication protocol, so it is helpful to first consider two distinct types of Bitcoin information: UTXOs and private keys.

UTXOs (unspent transaction outputs) encumber the protocol’s scarce information space. Think of the Bitcoin network as if it has space on a hard-drive, except instead of documents adding in size to 120GB, we have UTXOs adding in size to 21M BTC. When people say that there will only ever be 21 million bitcoins, what they mean is that there will only ever be a combined total sum of 21M BTC shared among all UTXOs on the network. It’s the information space encumbered by these UTXOs that has accrued market value.

Bitcoin UTXOs are scarce because one script, and only this one script, is locking up their value on the network. This script is unlocked by a corresponding private key. As far as the Bitcoin protocol is concerned, if one can resolve this script to the network by using the right private key, then they have the right to create a transaction with the UTXO. Because UTXOs are consumed in transactions (resulting in equally valued outputs at the other end), it is notable for our purposes here that they are best employed to explicitly transfer or lend this information space to a third party.

Private keys, on the other hand, are simply the secrets that allow this activity on the Bitcoin network. Because of the value that these secrets can be used to unlock, safeguarding them is imperative. These secrets can be known by a specialized third party offering certain assurances, much like a password manager, and thus they are well-suited to being “warehoused”.

Private Key Warehouses

In legacy finance, the role of a qualified custodian has typically been to safeguard legal title to financial products like securities. Perhaps because of confusion around what Bitcoin is, we have seen the emergence of institutions structured more like securities custodians than contemporary banks entering the space. Specialized custodians are explicitly aiming to fill the warehousing role, and they leverage the unique properties of the Bitcoin protocol to achieve this. At Knox, for example, there isn’t simply a big central storage unit and database of “bitcoins”. Customer UTXOs are encumbered by completely segregated private keys in an auditable multi-signature scheme, geographically dispersed and insured for the value of the UTXOs over which they exert control. The infrastructure is set up such that UTXOs can’t be unilaterally spent by internal operators–that requires the cryptographic authorization of the depositor that is in control.

The importance of this can not be understated. Whilst all Bitcoin participants should still be strongly encouraged to retain exclusive knowledge of their private keys, for many individual and corporate use-cases this is not practical. But warehousing private keys like this is not “reinventing banking” in the way detractors think it means.

Bitcoin private key warehouses (“custodians”) are tasked with occulting the knowledge of the private key that locks up the network value of their clients.

Given appropriate legal structures to ensure that keys are shared in a bailment relationship, technical assurances that these third parties cannot single-handedly consume UTXOs, and providing auditability through public addresses on the network, fractional reserves under such a system should not even be possible. At their most basic, these companies simply offer a private contract to keep a secret and occult their customer’s private keys. They’re security services for valuable, secret information with two major functions:

1. Act as a computational service provider

Apply signatures (information, text) with secret values (information, text) propagating the results of the computation (information, speech)

2. Act as a storage service provider

Hold onto secrets (information, text), to make 1. Possible

One of the reasons for using irregular deposits to custody fungible goods is that it’s impractical and prohibitively costly to return the exact same gold bar to its original depositor. But in Bitcoin, if it’s defined that the private keys themselves are what’s being shared, this is not only possible, but inherent to the system. While it is by no means trivial to provide these assurances and ensure rigorous key segregation, an advantage of Bitcoin’s digital nature quickly becomes apparent: once the methodology is defined and implemented, keeping private keys separate scales incredibly well, unlike a physical gold warehouse where costs would increase in lockstep with the number of customers.

Furthermore, Bitcoin participants shouldn’t trust that the services they employ are keeping these promises. While a certain segment of the Austrian school would argue to let a self-correcting free banking system simply run its course, we needn’t be so cavalier in Bitcoin. If a Bitcoin holder engages the services of a private key warehouse, auditable addresses should be demanded for the UTXOs that can be controlled by those keys.

In this context, Bitcoin’s apparent lack of fungibility (distinct UTXOs can be identified) is a feature, not a bug. Irregular deposits as defined by de Soto need not exist when we have a system that can functionally scale to segregate each customer’s private keys and addresses, while also being audited by the customer without needing to query the business’ servers.

Customers might also consider storing individual keys from a multi-signature wallet across different private key warehouses to provide an extra level of risk segregation assurance, thus requiring an incredibly complex, multi-party collusion to violate their expectation of safekeeping.

This is the technical, practical and philosophical beauty of multisig: it is consensus-enforced (non-simulated) shared ownership of a scarce asset. Until now, the concept of scarcity has described the exclusive usage and ownership of a given good by a specific individual. If someone is holding the only axe in the village, another can’t hold the same axe at the same time. It is scarce. There can be private contracts that simulate shared ownership amongst many peers, but these are not inherently enforceable, as any party can cheat. Thus, we need legal systems to punish such cheaters after the fact. Bitcoin, however, enforces this shared ownership in its very protocol, to such an extent that Max Hillebrand argues it is no longer simulated, but actual shared ownership. Of course, all of this is under the assumption that the right people keep their secrets safe.

With the fundamentals established, these assurances can be extended to services where Bitcoin is posted as collateral against a fiat loan. Obviously, a customer posting collateral can’t retain exclusive control over the asset — for example, the service might be forced to liquidate based on certain predefined scenarios. But there are interesting models such as Unchained Capital’s collaborative custody, where collateral posted against a loan is held in a 2-of-3 multi-signature scheme. Unchained Capital holds one key, another is with a third-party key agent (Citadel SPV), and the customer holds the final key. An auditable address for collateral is derived such that the customer can keep an eye on it, and having multiple parties involved can offer certain assurances. The third-party key agent must verify that a liquidation event is legitimate before Unchained Capital can claim those assets, while the customer can also work with the key agent to have collateral returned in the event that Unchained Capital fails or is otherwise unavailable. Remember, the business model for collateralizing loans ought not to be lending collateral back out as if the bank owns it: the model is instead to earn interest on the fiat loan. The collateral can simply be seen as insurance against default, and multisig schemes can be used to enforce this.

One final note: another reason for the deposit banks of old was for scalability. Bank notes served a legitimate use-case for divisibility and transport in a commodity money system. While there’s no guarantee for future scaling, the Bitcoin network doesn’t yet need the financial intermediary role of a money substitute, and it is hoped that the Lightning Network Protocol or a future protocol layer will provide this scalability that banknotes once provided without needing to derive centralized substitutes.

UTXO loan-banking

A clearly distinct class of financial infrastructure has also emerged in the early financialization of Bitcoin: interest-bearing accounts. If someone sends UTXOs to Ledn on the promise of earning a 3.6% return, it should be distinctly understood that the legal title to the information space encumbered by those UTXOs no longer belongs to the depositor. Rather, Ledn exercises property rights, ownership and control, with a debt owed to the depositor and interest paid out as a fee for the privilege.

As in historic loan banking, these UTXO loans function largely as you’d expect. There are typically term requirements for the deposit (the depositor can reclaim possession of the information space after a month or longer), and it is understood that the depositor is taking on the default risk of the company with which they hold this interest-bearing account.

If there is any gripe with this model, it ought to be in the marketing. Often, these products are implicitly marketed to help Bitcoin holders “start saving”. Where the loan banking model explicitly carries more risk than one would expect from a contemporary bank account (e.g. there is no lender of last resort and no FDIC-style depositor insurance in Bitcoin for now), it’s a savings account at a traditional bank that this market positioning brings to mind. To be blunt, these loans are more like an investment in the default risk of a fintech startup, while “saving” in the Bitcoin paradigm is a term best suited to securing private keys. After all, the supply cap of Bitcoin theoretically means that the purchasing power of UTXOs is preserved, unlike in the inflationary fiat paradigm where purchasing power is systematically diminished and investment is required simply to save. That aside, the fact that this loan structure has emerged clearly separated from the role of private key warehouse is welcome.

Subversion of Bitcoin

Having spelled out the features that Bitcoin offers its network participants, now isn’t the time to be complacent. Note that some companies are, indeed, engaging in practices that might simply recreate the trappings of the legacy financial system. Individual caution is needed.

I have written in the past about my thoughts regarding BlockFi, for the company appears indifferent to the opportunities of the Bitcoin protocol put forward in this article. BlockFi’s interest-bearing account is very high risk, but this is transparent enough and one might have few qualms with that (an 8.6% return on some deposits should be the only market indicator you need to establish this conclusion).

What might be worth more consideration in the context of the current thesis is that Blockfi also offers a bitcoin-collateralized loan. Presumably, one might expect the company to hold the Bitcoin collateral in an auditable, segregated wallet under a bailment relationship — as with Unchained Capital, you’d expect that their business model is to earn interest on the fiat loan being repaid while safely custodying the UTXOs posted as collateral. Alas, the UTXOs held under both the interest-bearing and collateralized schemes appear to be commingled and the company reserves the right to rehypothecate — that is, Bitcoin posted as collateral can be re-lent by BlockFi as if it were theirs, exposing depositors to additional counterparty default risk. This is very much akin to the contemporary banking system. The market is the great arbiter of such trade-offs, but given the assurances offered by the Bitcoin protocol it might be considered that competitors provide better assurances in the way they handle collateral.

Bitcoin Can Work With Banking

As most would have expected, it’s becoming very clear that Bitcoin is being financialized at a rapid rate. Fortunately, the nature of something truly scarce means that fractional reserves can not be sustained for long. Whether by design or accident, such schemes will tend to be discovered and collapse in the absence of a lender of last resort. But while this secures Bitcoin against any systemic risk — blocks will still be mined every ten minutes, oblivious to what participants do with it — such failures can cause a lot of suffering to those defrauded by them.

Bitcoin offers assurances that ought to be harnessed by alert network participants to ensure the safety of their holdings. By forcing a segregation between services akin to deposit banks (custodians) and loan banks, and demanding certain verifiable assurances from both, these services and participants alike can thrive while supporting the early financialization of Bitcoin and avoiding the trappings of Wall St. Both of these banking functions, with their different risks, are likely necessary for the ethical financialization of Bitcoin, so long as one remains alert.

Special thanks to Max Hillebrand, Ben kaufman and Ben Prentice for review and guidance, Stephan Livera for pointers and as always Thib and Daskalov for brainstorming, support and reviews.

Knox is working on the ethical financialization of Bitcoin with a focus on private key custody. If you would like to know more about how Knox can support the security of private keys, attempt to poke holes in our model or otherwise hear more, please reach out and speak to our team!