Bitcoin’s Town Square

| If you find WORDS helpful, Bitcoin donations are unnecessary but appreciated. Our goal is to spread and preserve Bitcoin writings for future generations. Read more. | Make a Donation |

Bitcoin’s Town Square

By Zane Pocock on Mempool Review

Posted June 18, 2020

Why mempools are the network’s most brutal information space

To the average Bitcoin participant, mempools are simply a list of pending transactions to check in on when they have a transaction to broadcast. But they are so much more.

Mempools are a bustling, brutal marketplace of pure data. They reflect all the knowledge of the pressures, needs, time preference and means of every single participant demanding transaction settlement on the Bitcoin network. And they distill all this knowledge into a real-time price signal anyone can interpret and interact with.

Mempools are the centerpiece of the entire Bitcoin economy. And they are totally underrated.

Note: mempools are tightly integrated with other components of the Bitcoin network, particularly mining and transaction verification, that are out of scope for this article to explore. We will uncover what we need to make everything clear, but this article is more focused on a mental model for understanding mempools than technical exactitude.

Thousands of Mempools

At its simplest abstraction, “the mempool”, short for Memory Pool, can be thought of as a database of pending Bitcoin transactions. These are transactions that have been broadcast by users but haven’t yet been included in a block. Because they have not been mined into a block, such transactions are considered “unconfirmed”.

We refer to “the mempool” here in quotes because this term is a colloquialism that neglects the true nature of how the Bitcoin network functions, and it’s worth correcting. While “the mempool” would imply that there is a single master list of unconfirmed transactions, there is no such certainty. Rather, every participant running a full node will have a slightly different version.

When we talk about “the mempool” we thus aren’t strictly talking about a ubiquitous information space. We’re talking hypothetically about all the transactions spread across all the mempools. Most mempools might have most of the transactions but the idea of “the mempool” is a shortcut that helps us make generalizations and perform economic calculations.

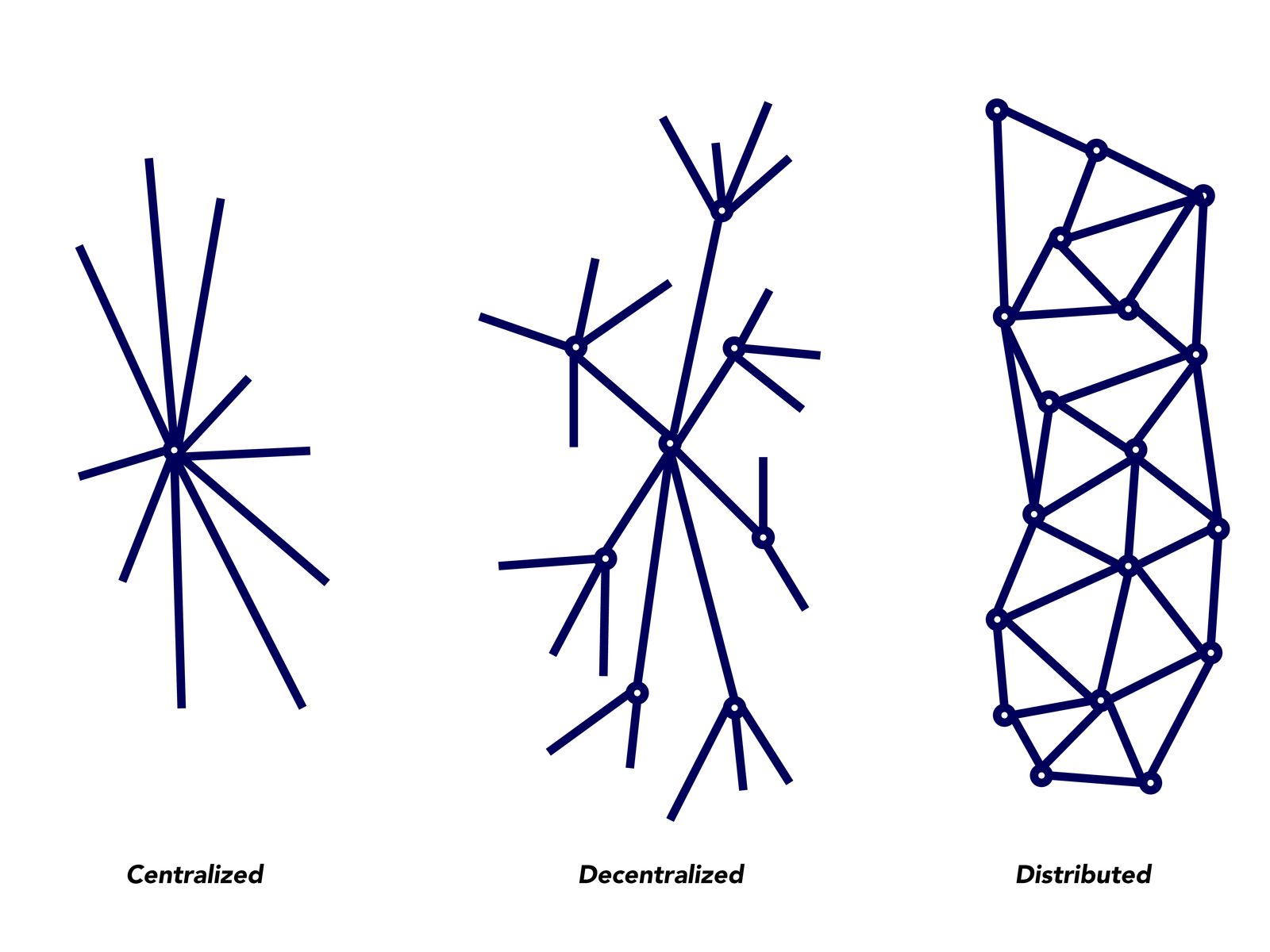

Why is this? The Bitcoin protocol functions such that each node represents an intersection on a distributed network, each with a unique set of connections to other nodes.

When a participant broadcasts a transaction to the network through a node (hopefully their own), that node will pass the transaction data on to the other nodes that it has direct connections with. These nodes will first verify that the transaction is legitimate, and if so, they will update their list of unconfirmed transactions to include it and pass the data on to the other nodes that they, in turn, are connected to. Those nodes will repeat the process until the percentage of nodes with a copy of this transaction approaches 100%. This is called a transaction relay.

So, what happens when those transactions are mined into a block? While humans think of miners as huge industrial enterprises hashing transaction data at great cost, nodes on the Bitcoin network simply interact with miners as they do with any other node. These nodes, which seen through a human lens happen to “mine”, keep their own version of the mempool from which they select transactions to include in a block when they successfully meet the current network criteria, roughly every ten minutes. Those blocks then propagate back through the network in much the same way as transactions, with each node verifying that they meet certain criteria, updating their copy of the settlement ledger (“the blockchain”), and passing the message on to others. Each individual node first tries to validate these blocks with the transactions they already have in their mempool and request any missing transactions from peers, after which they flush these transactions from their mempool as they are no longer “unconfirmed”. For a high-level understanding of some more nuanced parts of this process, Marty Bent published a wonderful graphic explanation by Bitcoin Core contributor Amiti Uttarwar.

This is why it’s important to understand “the mempool” as a collection of independent mempools: it’s easy to accidentally equate the idea of a shared mempool with the certainty of the blockchain and its settlement assurances. While every participant eventually stores an identical record of final settlement (the blockchain), there is no such record of truth for those transactions awaiting settlement. For our purposes, understanding “the mempool” as a marketplace, this is important: calculations we might like to make will always be probabilistic.

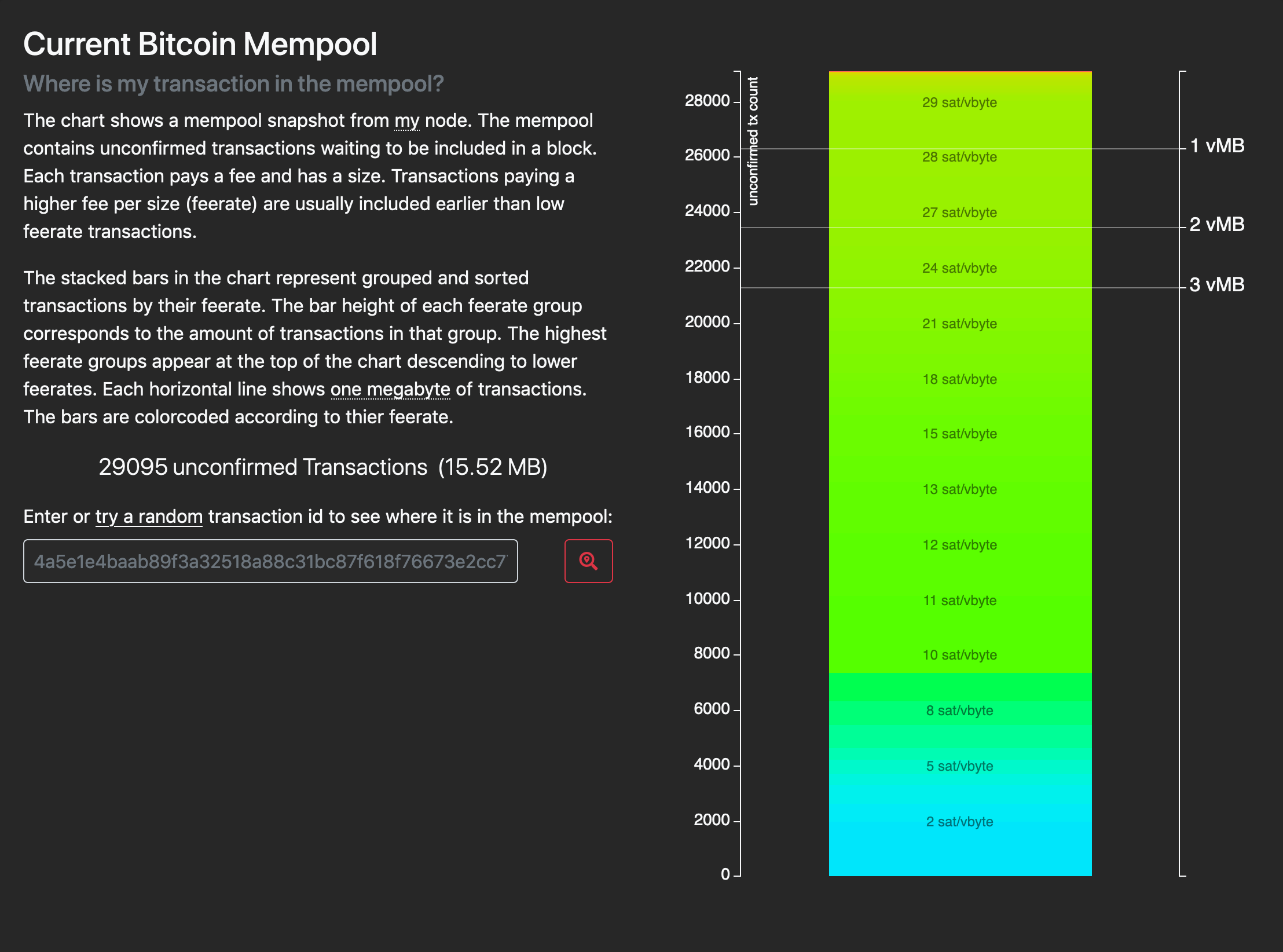

While the Bitcoin network is best seen simply as a communication protocol dealing in scarce information space, mempools are a clearing house for the allocation of that information space. Users of the Bitcoin protocol can roughly keep track of their unconfirmed transactions through metrics gathered from their own mempool. If you have initiated your own transaction before, you might have noticed that wallets such as Electrum will tell you its “position in mempool” expressed as, say, “13 MB from tip.” As far as a miner is concerned, the two most important data points about a transaction is its size (in terms of data requirements, not value) and the feerate it’s willing to pay. If you imagine your mempool as a list of transactions ordered by the feerate each is paying, this is very roughly telling the participant that their transaction is estimated to be about 13 MB worth of >1 MB blocks away from being included because that is how high it is bidding, so say 11 blocks or 110 minutes assuming ten-minute block times (to more technically proficient readers, please bear with me here—I recognize this is quite a simplification).

The Use of Knowledge in Bitcoin Society

Austrian economist F. A. Hayek would have loved mempools. In his 1945 essay The Use of Knowledge in Society, he illustrates the profound importance of price signals by making the case that every economic actor has some of the information all of the time, but all of the information none of the time. At its most simplified, his argument is a knock-out refutation of the idea of a planned economy: how could a central planning board possibly keep up with the dynamism of each individual component of the economy? Price signals and their fluctuations are immensely powerful as they tend towards carrying all of this information, despite no single individual needing to know exactly why certain prices have moved in certain directions. Hayek’s insight was to understand that in all cases, what is known by a single agent is only a small fraction of the sum total of knowledge held by all members of society. A decentralized economy thus complements the dispersed nature of information spread throughout society. Much like transactions propagating through mempools, specific and granular market dynamics can efficiently propagate through an entire economy via price signals.

“The marvel is that in a case like that of a scarcity of one raw material, without an order being issued, without more than perhaps a handful of people knowing the cause, tens of thousands of people whose identity could not be ascertained by months of investigation, are made to use the material or its products more sparingly; that is, they move in the right direction.” —F. A. Hayek

It’s no surprise that in our present Information Age, Hayek’s essay is gaining prominence anew. For example, The Use of Knowledge in Society is central to Jimmy Wales’ philosophy for how to manage the Wikipedia project. At the outset he would “imagine a world in which every single person on the planet is given free access to the sum of all human knowledge.” Extending Hayek’s thesis beyond the purely economic realm and into all knowledge, what is more likely to be successful? The centrally-planned mission of Google to “organize the world’s information”, or the organic, open Wikipedia built on the foundational Hayekian idea that “when information is dispersed (as it always is), decisions are best left to those with the most local knowledge?”

Applying these ideas back to the economic information spaces of Bitcoin, the impactful nature of mempools becomes apparent. When a participant is attempting to broadcast a transaction to the Bitcoin network, it matters not why their mempool is giving them certain indicators. But those indicators carry enough real-time knowledge from the activity of the entire global Bitcoin economy to make the best economic decision for those UTXOs they control at that point in time.

If, for example, a network participant’s mempool is starting to fill up, one might say the network is getting “busy.” This might be because more people were buying and withdrawing Bitcoin from exchanges in anticipation of some bullish event. It might be because participants are nervous about the solvency of a particular exchange and they’re running for the exits via base-layer final settlement. It might be because a large actor is consolidating UTXOs … And so on and so forth, and in all sorts of combinations. But the basic principle of interacting with mempools is this: when a block is mined, transactions are removed from mempools. Others continue to fill it up. And sometimes there’s a traffic jam if new transactions arrive at a higher rate than they are cleared.

Many of these hypotheses can, of course, be tested with further research, but what’s important for the average actor is simple and doesn’t require any further knowledge: for whatever reason, more transactions are awaiting settlement. As a result, your mempool is telling you that you’ll have to pay up for your place in the limited information space of a newly minted block.

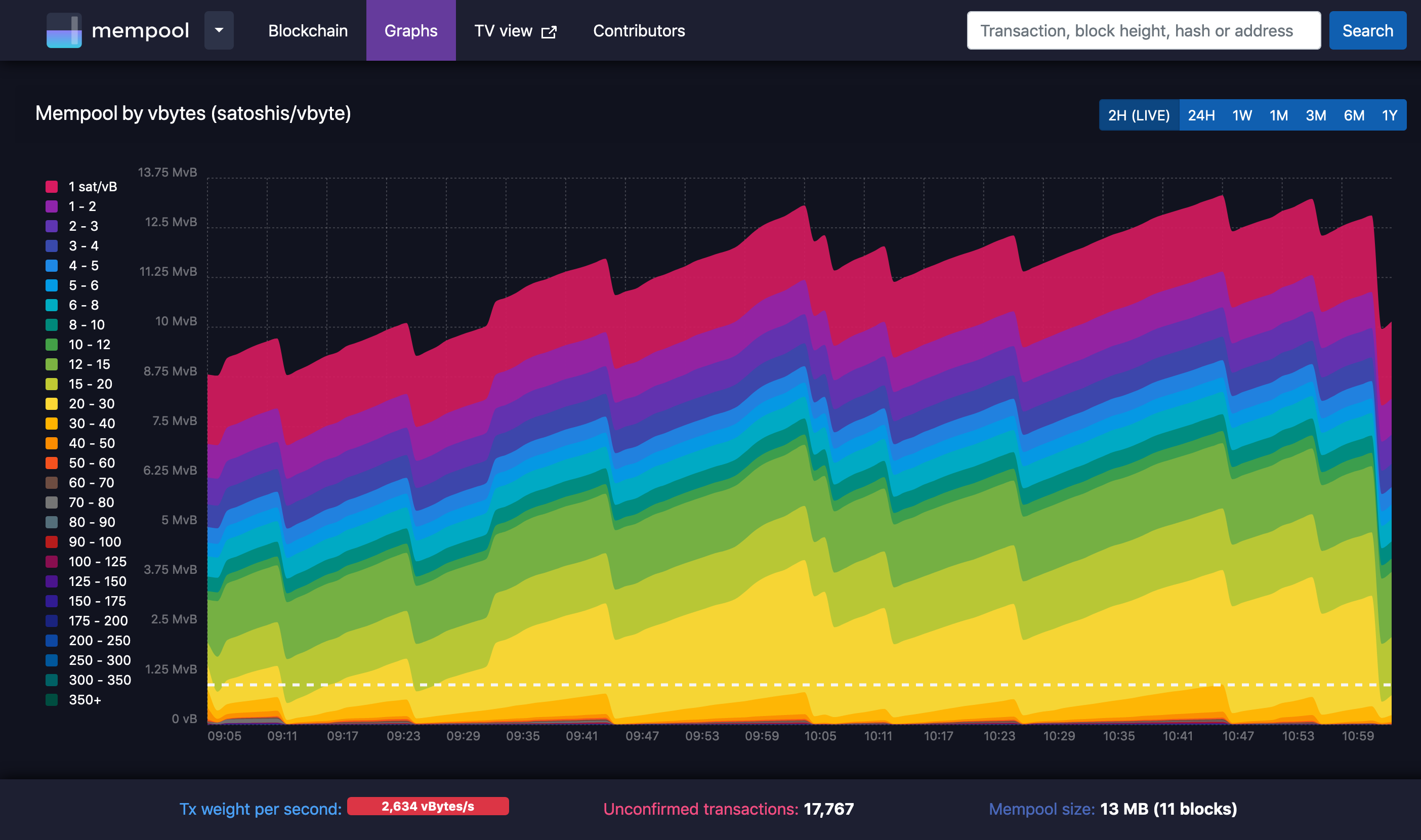

This principle can be illustrated with tools such as the beautiful https://mempool.space/. On the live graph view below, stratified by feerate, it can be observed that mempools have been getting slightly busier over the course of the past two hours. With 13MB of unconfirmed transactions outstanding, the tool estimates the network will require the next 11 blocks to clear if no new transactions are added. We don’t need to know why. It is helpful enough that we can observe the entire global demand for blockspace (i.e. demand for inclusion in a future mined block) in this concentrated, open knowledge. The white dotted line on the graph shows us which bids are most likely to be included in the next block. Though this is no guarantee, it’s a calculation we can make based on what we know to be one of the primary miner incentives: earning as much from fees as possible.

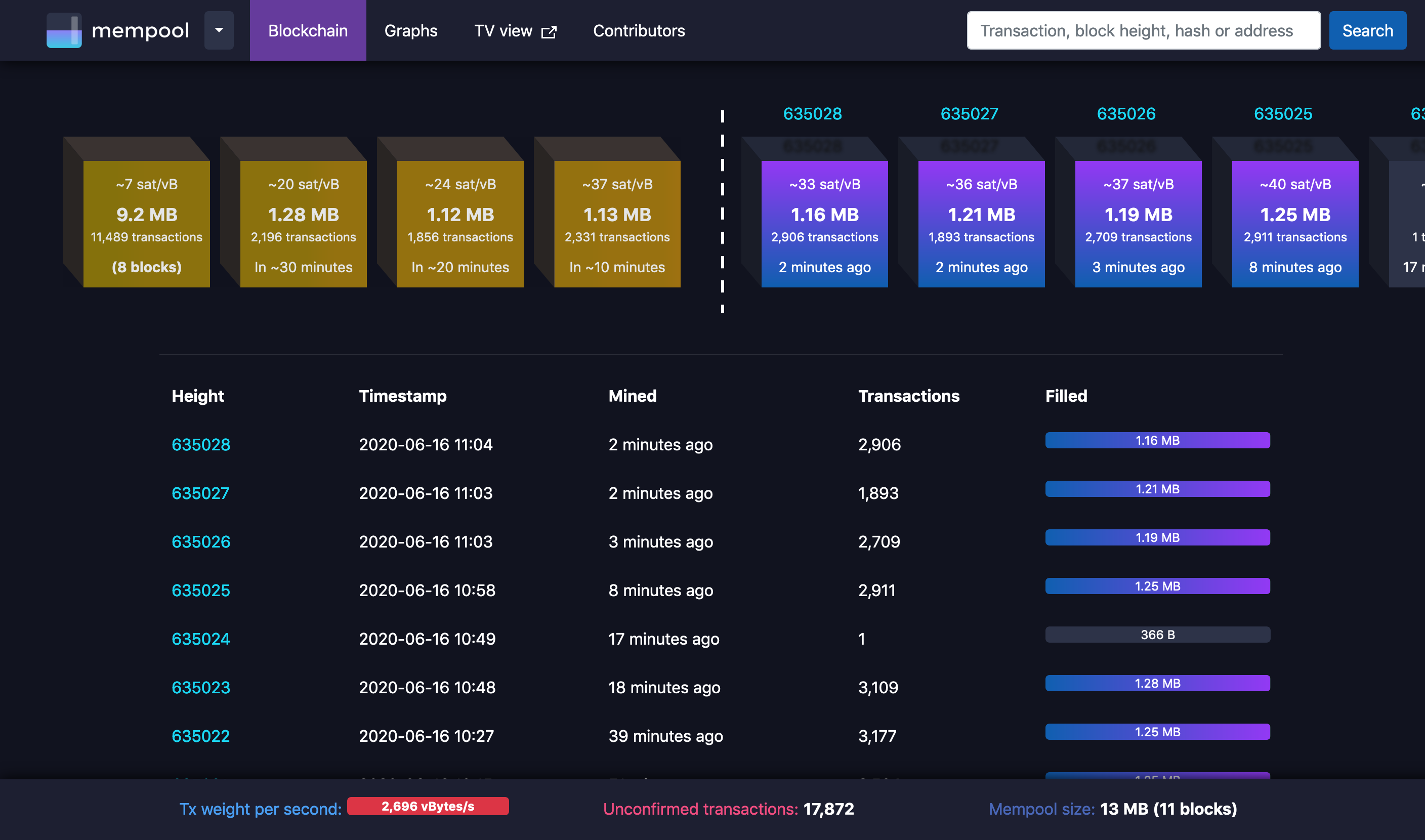

From the knowledge of global blockspace demand illustrated in the mempool visualization above, we can go on to calculate estimates for Bitcoin’s native price signal—feerates—and other knowledge such as estimated time to settlement. In the “Blockchain” tab below, the tool takes knowledge such as the current state of the mempool, the protocol’s allowable block size, and the protocol’s target block time of ten minutes to estimate the price a transaction must bid to be included in n number of blocks, or n * 10 minutes as measured in human time.

Based on the needs and knowledge exclusive to each individual participant looking to use the protocol at any given moment in time, they make their own calculations for the fee they can afford to pay and the urgency with which they need their transactions reflected in the global ledger of final settlement. And they perform this calculation against the entire sum knowledge of every single other participant using the network across the entire globe, all concentrated into these few signals.

Bitcoin’s Native Market

There is something underappreciated about the nature of mempools. Taken together as the abstract idea of “the mempool”, they represent a bustling global marketplace of pure distilled information, interpreted in line with other knowledge to give an idea of the global demand and availability to settle transactions, with no group of people responsible for anything—just individuals doing what’s required to meet their needs with whatever means they have available to them.

From the Heyekian perspective, specific knowledge of the external factors influencing the price signal for settlement are irrelevant to the individual participant—what your mempool tells you is all you need to know. It’s a pure, network-native marketplace that can be efficiently interacted with in the complete absence of any external inputs. You’re using information space (scarcity encumbered by UTXOs, measured in units of “bitcoin”) to buy a position for settlement in another form of information space (block space) based on summarized global knowledge you can glean from yet another, more ephemeral, information space (mempools).

The mempool is Bitcoin’s town square. It’s a brutal, unrelenting marketplace—the exchange at the center of the entire Bitcoin network’s economic activity. Everyone is bidding their worth to anyone who will listen. Sometimes they won’t be heard and they’ll miss a good opportunity. Sometimes they’ll bid low and get lucky. This is a marketplace that exists purely in Bitcoin’s information spaces. No restricted access via on or off ramps. No one pleading their case for a charitable interpretation of their needs. Just a ruthless, global settlement market native to the Bitcoin network. If Bitcoin does indeed become the center of global commerce in the years to come, the mempool will be the single most important component to watch for many of those using it.

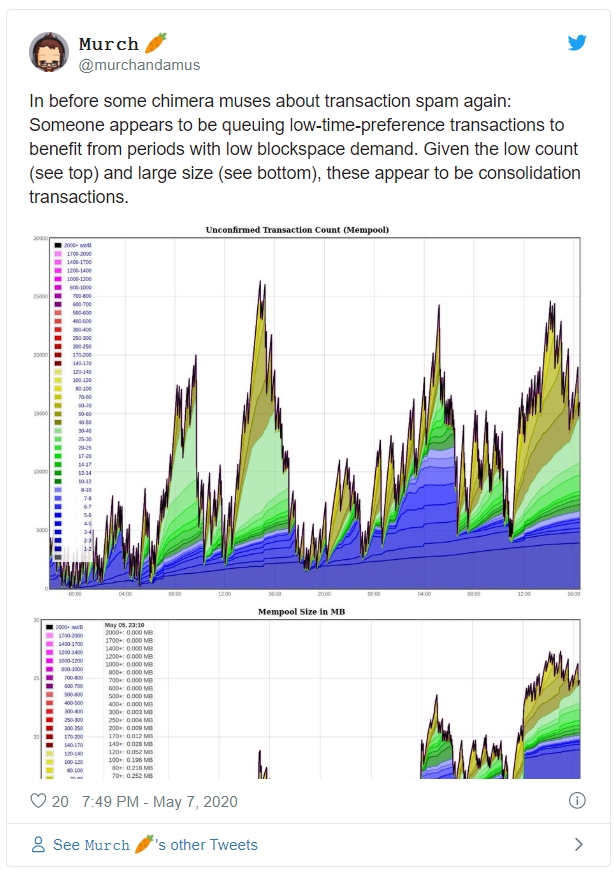

In this pure anarchic (meaning an absence of authority, not chaos) global market, daily news updates will attempt to interpret contributing factors to make predictions for concerned participants. High profile participants will pontificate on what certain events “mean.” Gossip will spread about large participants wasting their precious, scarce UTXO information space overpaying on fees. So too will companies be frowned upon and called out for such inefficient use of blockspace that they affect the entire network, such as the case of the daily BitMEX broadcast at 13:08 UTC, which regularly changes the shape of the mempool and forces other participants to adjust their bids or expectations as a result. The author of that piece, B10C, is an early example of what might be considered a mempool researcher. Prolific Bitcoin StackExchange contributor Murch might similarly be considered thus.

For similar graphs: http://bitcoin-mempool.info/#0,24h

For similar graphs: http://bitcoin-mempool.info/#0,24h

When people talk about the Jevons paradox as it relates to predictions about Bitcoin’s future, this network-native marketplace for transaction settlement will be the centerpiece of such a dynamic. Jevons paradox is the observation that increasing efficiency from technological progress does not alleviate pressures on the underlying commodity’s use, but instead tends to increase the rate of consumption from rising demand. Thus, as efficiencies are found for Bitcoin’s blockspace—pooling transactions to share costs, second layer solutions clearing in isolation and only settling intermittently, etc.—the opportunities they bring for more participants and more use cases will be profound.

And without talking to another soul or learning any of the specifics, all of this will be reflected in the simple knowledge we can glean from our mempools.