Bitcoin’s Existential Crisis

| If you find WORDS helpful, Bitcoin donations are unnecessary but appreciated. Our goal is to spread and preserve Bitcoin writings for future generations. Read more. | Make a Donation |

Bitcoin’s Existential Crisis

Cryptocurrencies lack leaders — they have no single source of truth. Philosophically, this can get complicated.

By Nic Carter

Posted October 31, 2018

Identity is a troublesome thing — for humans, nonliving systems, and objects alike, especially as they change over time. Humans can rely on essential traits like DNA to serve as stable markers of identity, and nonliving systems (corporations, for example) can rely on governments and legal systems to anoint them with stable identities.

Cryptocurrencies and public blockchains, though, have no such privilege. They aim to decentralize their leadership without relying on a single third party in establishing their identity. Instead, they rely on subjective social- and economic-consensus mechanisms. While some cryptocurrencies use foundations or corporations to resolve disputes and arbitrate core issues of identity, that’s a fragile approach and generally not consistent with the objectives of these systems.

The most sustainable approach for cryptocurrency is to dispense with the kingmakers, bite the bullet, and leave it to intersubjective consensus. This requires a commitment to a set of practical values that constitute the essence of the system. Systems with more internal consistency and more universally agreed upon value sets are better equipped to last.

The Ship of Theseus Paradox

A classic question-of-identity paradox goes like this: The Greek hero Theseus asks his crew to rebuild his travel-worn boat, and they replace it plank by plank. When the task is done, he ponders whether his restored boat is really the same boat as before, given that all the parts have been replaced. He further considers that if he were to ask his crew to build a new boat with the planks of the old one, two boats would both have a credible claim to being his old vessel. But which is the true original?

It’s compelling because there’s no clear answer. The story shows us that the identity of an object isn’t absolute — it’s assigned, rather than essential.

This comes up even in human contexts: Your cells replace themselves so often that the present you shares very little physical matter with the version of you that existed a decade ago; prisoners held for violent crimes are paroled with the assertion that they have become “a different person” in some vital sense; or — perhaps the simplest example — you might at some time have credibly apologized the day after an intoxicated argument by asserting, “I wasn’t myself last night.” In all these cases, the person is clearly the same person in one sense of identity, but in another sense, many of the traits that make up the person are mutable.

This is okay because the systems that depend on humans to have stable identities can account for the fact that personalities, memories, and physical selves change over time. On a day-to-day basis, our friends and family recognize us, even with decades-long gaps. Low-stakes identity challenges can depend on the recall of certain things we know about ourselves — Social Security numbers, passwords, birthdays, mom’s maiden name, or the name of your first pet. And high-stakes identity challenges can depend on physical markers like fingerprints, retina scans, or DNA tests.

If you build a system meant by its very nature to dis-intermediate third parties and exist independent of governments and legal systems, then you have a problem.

But those human identifiers all rely on the involvement of third parties. And, similarly, certain nonliving systems can use third parties to establish their sense of identity. Creating legal entities like corporations solidifies abstract, malleable sets of individuals and ideas and gives them persistence over time, even if their staffs and business models change entirely. And granting legal assignments like trademarks or patents gives ideas and concepts persistent identity as well as gives their owners exclusivity.

Most nonliving things don’t have these kinds of third-party tiebreakers, though, making them especially vulnerable to Theseus problems. If you build a system meant by its very nature to dis-intermediate third parties and exist independent of governments and legal systems, you have an identity problem. And that problem is one public blockchains face.

The Theseus Problem of Blockchains

While I do not much like the term “blockchain,” I’ll use it here for simplicity. What I am referring is not enterprise blockchains but rather open and permissionless systems like Bitcoin or Ethereum. These two blockchains, in particular, have suffered severe crises of identity over the years.

For Bitcoin, its crisis turned on whether it should attempt to scale up as a P2P payment network immediately (and raise throughput) or whether it should pursue a layered approach. Ethereum had to contend with a reckoning in which participants had to determine their desired level of immutability in response to the DAO exploit.

Both sides had credible cases. There was no constitution that specified, one way or the other, that Bitcoin’s blocksize was permanently capped or that Ethereum couldn’t use a hard fork to reverse (ostensibly) illicit transactions. (Ethereum has a formal specification, but that is a more technical rather than constitutional document.) Instead, there were messy processes of social-consensus formation, appeals to authority, deep readings of original documents, and, ultimately, rancorous splits.

These are not incidental problems or one-offs; they are a core feature of decentralized systems. Public blockchains like Bitcoin, with no recognized leadership, are exposed to competing views of what they are and should be. In a previous post, Hasu and I made an effort to chronicle those disparate visions over time. For sure, there are developers, entrepreneurs, thinkers, miners, and capital allocators who wield disproportionate influence in Bitcoin, but no single individual or institution exerts unilateral control. Therefore, divergent views of the protocol cannot simply be quashed.

Two Approaches to These Problems

How do we cope with this? There are two ways: One is expedient and the other is more sustainable.

The first and most common method is to give a corporation or foundation rights to a trademark, as is the case with Tezos or EOS.IO. This is the default for non-Bitcoin blockchains and gives an entity the legal force to anoint and ratify a single chain. Of course, no one is bound to follow this, and there could be a fork of Tezos that everyone mutually agrees to use.

However, the trademark carries certain legal protections, and if a fork tried to retain the name, the trademark owner would have recourse, at least where the fork tried to interact with regulated institutions. In this case, the trademark is just one manifestation of the core issue, which is confirmation that the leadership of a blockchain is seeking authoritative ratification of their control. Other activities this entity might engage in would be pressuring exchanges to use one ticker over another or support one fork over another as well as spreading a consistent message to the media. All of these give the entity de facto control over which fork is chosen in a dispute.

Consider just how little persistence Bitcoin’s components have. The entire codebase has been reworked, altered, and expanded such that it barely resembles its original version.

The other approach is to throw caution to the wind and spurn any external marker of identity, relying instead on an intersubjective consensus, such that the system can change over time while remaining faithful to its original goals. This is the approach leaderless (or, more accurately, leader-minimized) systems like Bitcoin and Monero go for. Of course, there are influential individuals in both systems, but neither has a foundation or corporation in control of a trademark or a clear decision-making body. Many critics would say that Bitcoin Core, as the author of the dominant implementation of Bitcoin, wields disproportionate control, but that’s a reductive reading. It is not an official body, and the dominant implementation that they create does not define the essence of Bitcoin but rather its instantiation. Pierre Rochard puts it well:

Bitcoin’s block and transaction validity rules are a social consensus that is automated with software. Where they diverge the software is wrong. This is an uncomfortable reality for proponents and detractors alike.

This concept deserves formalization and a lengthier treatment, and I will cover it in a more detailed manner in a forthcoming post.

To pause for a second, consider just how little persistence Bitcoin’s components have. The entire codebase has been reworked, altered, and expanded such that it barely resembles its original version. Core features like multi-signature transactions and pay to script hash have been added over the years, and the protocol only loosely resembles the system described in the white paper — which itself is not a constitution but rather an introduction and teaser. None of the original nodes from 2009 are still running (to the best of my knowledge). Mining has become industrialized and has virtually nothing in common with the hobbyist mining of the early days. The leader has left, as have many of the early developers and stewards of the system, and new sets of developers have sprung up in their place.

The registry of who owns what, the ledger itself, is virtually the only persistent trait of the network, but the ability to copy it at will means it can be splintered. The Bitcoin Cash fork copied the UTXO set and started a new history while retaining the old balances. So it is largely trivial to copy the history and make a claim to the name. Indeed, this was exactly the strategy employed by Bitcoin Cash proponents — strident appeals to Satoshi Nakamoto’s vision.

To be considered truly leaderless, you must surrender the easy solution of having an entity that can designate one chain as the legitimate one.

Their argument was, in effect, that Bitcoin Cash more closely recaptures the essence of Bitcoin. Bitcoin may own the name, but we are closer to the system as intended by its creator and, hence, the true heirs. And they were free to do this because Bitcoin has no foundation, corporation, or entity that sets policy and lives entirely outside of the government, which ultimately adjudicates decisions like these in more conventional contexts. The Bitcoin/Bitcoin Cash struggle was so bitter precisely because there is no single entity that can anoint a true Bitcoin, so it had to be fought in the market, in the media, and in the minds of proponents.

Many critics identify this struggle as a shortcoming or flaw of a distributed system and propose alternative mechanisms to adjudicate disputes. Whether these will work are an empirical matter, but ultimately, the tradeoff remains. To be considered truly leaderless, you must surrender the easy solution of having an entity that can designate one chain as the legitimate one. Political consensus as to the true, genuine protocol must be continually sought and found. Without a stable identity, the system is guaranteed to splinter into pieces.

One Solution to Leaderless Identity

How can you have persistence of identity in a distributed, leaderless system? The cheap solution of having a single entity take de facto or de jure control is unavailable in this context. In fact, the answer is already quite established, although it hasn’t been much discussed. The way that Bitcoin has survived a decade of identity crises, absent any single leader, is this: It has a robust and mutually understood set of ideals that constitute the essence of the system.

The stronger the consensus around these shared ideals, the easier warding off competitors and resisting fragmentation becomes. Additionally, the market mechanism of pricing forks (sometimes prior to their birth through futures) enables individuals to receive powerful informational signals about what their peers are intending to do, which propagates consensus-forming signals efficiently.

During the Bitcoin Cash fork, the core question was whether Bitcoin is a protocol for small, P2P payments at the expense of node operators or a system for cheaply verifying P2P payments at the expense of expediency and short-term scalability. The resounding answer (although some still disagree) was the latter.

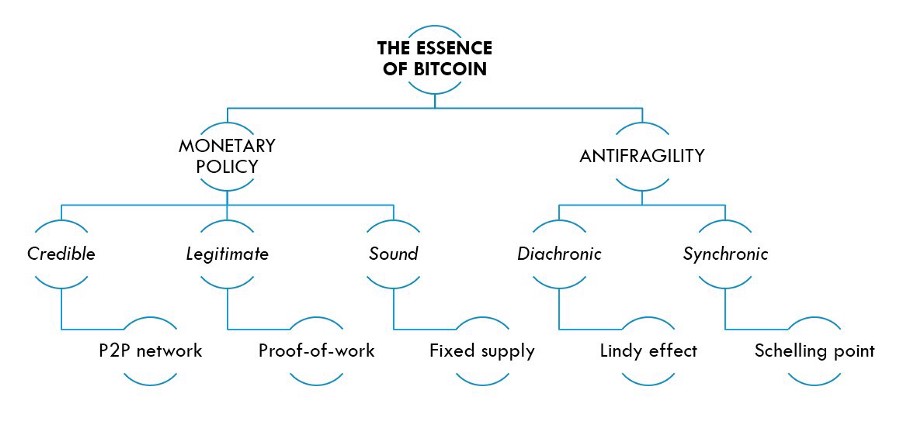

The challenge is that these rules cannot be “found” anywhere. Much like the U.K.’s government, there is no single written constitution. The rules aren’t in the white paper, which is incomplete in many respects. They aren’t exclusively in Satoshi’s writings on the mailing list or the forum — and given his departure after two years, Satoshi sought to resign from the position of ultimate arbiter anyway. The system is best described by the original codebase, although that has changed over time. More fundamentally, the core values of Bitcoin are an intersubjective agreement around a few concepts. David Puell makes a credible attempt to capture it here:

Source: David Puell

Source: David Puell

In fact, codifying and refining these rules is our challenge. By leaving, Satoshi left that task to us. Consistently define the protocol, give it a soul, and let it grow and adapt while being true to its original essence. This is an ongoing challenge, and we learn more and more about its essence with each passing battle, hostile fork, and attempted corporate takeover.

Ultimately, the commitment of the Bitcoin community to these ideals may represent a source of risk. Absolute commitment to the sound monetary policy (the 21 million hard cap) is a core virtue of Bitcoin but limits its design space and ability to pivot if the fee market doesn’t work. But this is the tradeoff Bitcoin has opted for. Other protocols instead sought a more malleable set of core values, relying instead on appointed institutions or well-defined leaders to designate the path forward. The more corporate and top-down these are, the less they rely on a shared identity; in other words, they become empty and soulless. I don’t believe there’s any substitute for diving in at the deep end and relying on essence rather than top-down decrees.

Toward a Bitcoin Ontology

In its 10th year, Bitcoin continues to struggle with these metaphysical issues. It suffers from more existential crises than a philosophy undergrad reading Kierkegaard for the first time. And the reason is that Bitcoiners are strongly opposed to a clear hierarchy for decision-making in Bitcoin. The lack of a benevolent dictator or philosopher king for Bitcoin is held as a strength, even if that makes decision-making less efficient.

In this context, it is not only difficult to forge consensus on key technical issues but also to organize the expenditure of political capital to actually implement those changes. The dispersion of decision-making power and the lack of a unified developer entity is the “problem of governance” that Bitcoin is said to suffer from.

But, here, the disease is also the cure. Bitcoin’s lack of governance is what makes it interesting. It’s a set of rules for moving money around that is very difficult to influence in any way whatsoever. Other open-source projects have benevolent dictators, but in a high-stakes game where the developers can serve as kingmakers for how resources are allocated in society, it’s wise, in my view, to make interfering with the protocol as difficult as possible. Of course, development occurs, but certain core attributes are walled off and considered largely untouchable.

As for the problem of a stable identity, absent a single foundation that maintains the trademark, Bitcoin must make do on its own. In practice, users, exchanges, miners, businesses, and developers engage in an ad hoc, socio-political process of adjudicating between competing visions of Bitcoin.

I expect this debate will end with three divergent philosophical stances within the Bitcoin camp, although it has implications more generally:

First, you have what I call “essentialists” and “materialists.” Essentialists, like myself, believe that the actual code is just a representation of some more fundamental values that the code is trying to express. Essentialists are amenable to rollbacks if something goes wrong in extreme cases because, at that point, the code will have been a poor expression of the form and can be overridden.

I expect there will arise a rival camp of materialists who believe the code is supreme and, in fact, represents the actual substance and reality of the system. Materialists are fond of saying things like “Bitcoin Core is Bitcoin.” They don’t buy the argument that Bitcoin Core is just an implementation of a more nebulous, uninstantiated specification. They often believe that the creators of Bitcoin Core control Bitcoin more generally.

Just as certain Supreme Court justices are strict constructionists and other justices are loose constructionists, it is the same with Bitcoin.

Leaving materialism aside, essence and essentialists — in practice — come down to differing interpretations of the written materials that Satoshi left us, the broader cypherpunk canon, and subsequent empirical findings (such as asserting that the SPV scaling model Satoshi described doesn’t work). Just as certain Supreme Court justices are strict constructionists (believing the Constitution must be interpreted as written) and other justices are loose constructionists (believing the Constitution is a living document that we have to interpret in context), it is the same with Bitcoin.

So, further stratifying the essentialist camp, let’s call the white paper enthusiasts “intentionalists” and their opponents “anti-intentionalists.” Intentionalists tend to think Satoshi’s vision was scaling on the base layer while anti-intentionalists tend to think Satoshi’s precise vision is irrelevant and that what matters more is the system he gave us and its evolution over time. Note that anti-intentionalists are still essentialists. They believe that Bitcoin should be able to adapt while remaining true to its essence but that its exact instantiation doesn’t have to be true to the original specification.

Labels can be dangerous, and excessive labeling is usually not very useful. But these three factions — materialists, intentional essentialists, and non-intentional essentialists — are what I’ve identified, and I think making the lines clear will help us clarify any debate.

The last year has been a period of relative respite in the war over Bitcoin’s soul. However, the battles will continue. This is the nature of the system; it cannot possibly be another way.