Bitcoin’s Energy Consumption

Bitcoin’s Energy Consumption

A shift in perspective

By Gigi

June 10, 2018

You might have heard that Bitcoin wastes a tremendous amount of energy. You might also have heard that Bitcoin will use half a percent of the world’s electric energy by the end of the year, the computations used for mining don’t do anything useful, and if the current rate of growth continues it will suck up all the energy and we are all going to die.

You might have heard that Bitcoin wastes a tremendous amount of energy. You might also have heard that Bitcoin will use half a percent of the world’s electric energy by the end of the year, the computations used for mining don’t do anything useful, and if the current rate of growth continues it will suck up all the energy and we are all going to die.

I don’t want to dispute the numbers or compare Bitcoin’s energy usage to the current banking system. I simply want to offer a shift in perspective.

Bitcoin is Offensive

Bitcoin is a global, permission-less, censorship-resistant network. Its nature is inherently offensive. It offends governments, bankers, and central authorities alike. Hell, offending banks was the whole point of this experiment in the first place.

At first glance, Bitcoin is the worst database ever devised by mankind. In addition to being seemingly inefficient and slow, it is eating up computational resources at a mad pace and consumes as much energy as a small country.

“In comparison to modern distributed databases, blockchains are slow, ponderous, unnecessarily redundant and overly paranoid.”Dhruv Bansal

As Nick Szabo so succinctly put it: “Bitcoin offends the sensibilities of resource-conscious and performance-measure-maximizing engineers and businessmen alike.” It also offends our globally shared understanding that wasting energy is bad, and energy-efficiency is always good.

According to a recent paper “the Bitcoin network can be estimated to consume at least 2.55 gigawatts of electricity currently, and potentially 7.67 gigawatts in the future, making it comparable with countries such as Ireland (3.1 gigawatts) and Austria (8.2 gigawatts).”

It’s easy to be concerned, outraged or offended. “Did you know Bitcoin uses as much energy as Austria? Baby cows are dying because of Bitcoin!”

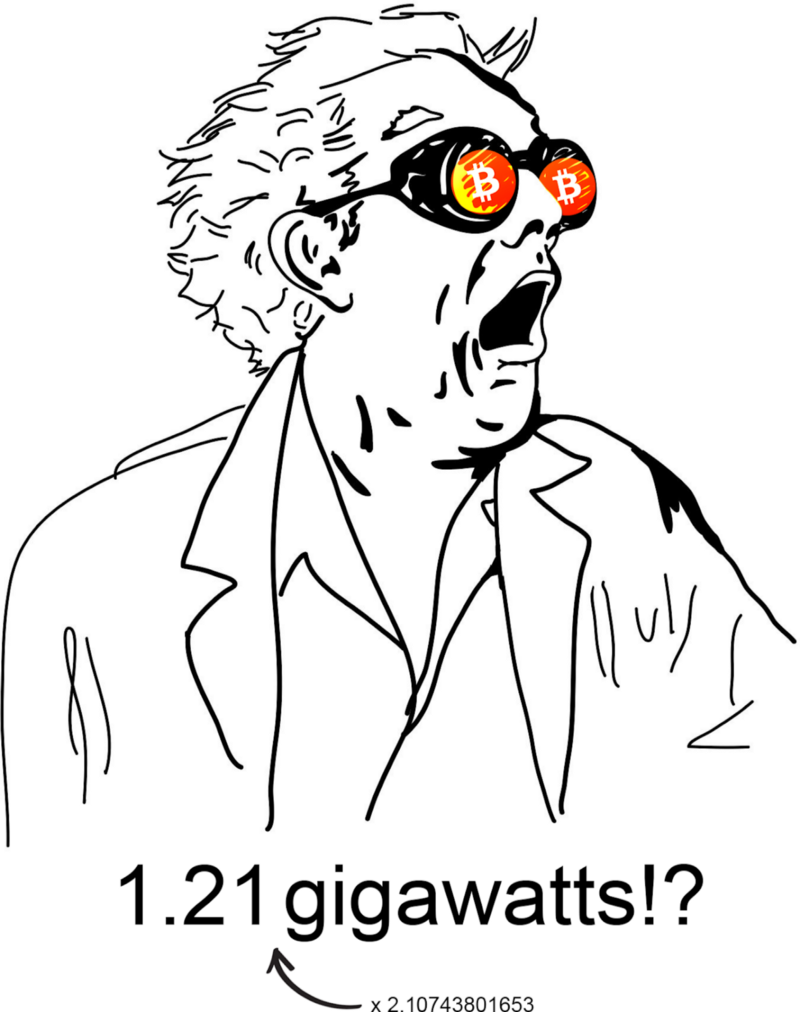

What-what the hell is a gigawatt?

What-what the hell is a gigawatt?

To understand why all these gigawatts are necessary for the Bitcoin network to function properly and securely, we will have to take a closer look at the nuances of mining.

Mining Blocks and Coins

The name “mining” stems from the proposition that bitcoin has more in common with gold and other precious metals than paper money. Satoshi made this clear in one of his posts.

“In this sense, it’s more typical of a precious metal. Instead of the supply changing to keep the value the same, the supply is predetermined and the value changes.”Satoshi Nakamoto

Hence bitcoins are not printed, they are mined. Even though we talk about “mining bitcoins” all the time, keep in mind that it isn’t bitcoins which are mined. Blocks are mined, and miners are currently rewarded with new bitcoins if they find a valid block. Miners are rewarded because finding new blocks is inherently difficult. The system is set up in a way that the difficulty of finding a new block is adjusted automatically so that a new block is found every 10 minutes on average. Differentiating between “mining bitcoins” and “mining blocks” helps to point out a couple of things:

First, that the rate at which bitcoins are mined is decoupled from Bitcoin’s energy use. If everyone would decide to double the energy spent on mining, the number of bitcoins mined would not double as a consequence. The rate of supply is fixed, no matter how much energy you choose to expend for mining.

Second, that miners do a lot more than bringing new bitcoins into existence: maintaining the security and continuity of the network, confirming transactions, and signaling their support or rejection of network changes, to name a few. Not all of these require an excessive amount of energy, which is one of the reasons why running a full node is important.

Third, that mining is not a fixed process. Both the mining reward and the mining difficulty are dynamic and thus will necessarily change over time.

Fourth, that mining is supposed to cost a lot of energy. It is computationally expensive by design, which is why Satoshi chose to reward people extra for expending this energy. It is the main ingredient of the Nakamoto Consensus. It is the work in proof-of-work. It is absolutely essential.

Without a closer look at the mining process, it is easy to confuse the energy-intensive process of finding valid blocks with “finding new bitcoins”. From this perspective, it seems like all this electrical energy is transmuted into new bitcoins.

This is wrong.

The energy expended acts as a barrier which protects the public ledger. The creation of new bitcoins is just a side-effect.

Cryptographic Walls

Until very recently, securing something meant building a thick wall around whatever is deemed valuable. We all know how to do this, and we all agree that this is a sensible thing to do.

The new world of cryptocurrencies is unintuitive and weird. There are no physical walls to protect our money, no doors to access our vaults. Bitcoin’s public ledger is secured by its collective hashing power: the sum of all energy expended to do the work in its proof-of-work chain.

Thus, we can think of Bitcoin’s energy usage like a giant wall — a sort of electrical force-field — which secures all bitcoin balances of all users, now, and in the future.

It is hard to say how much energy has to be expended building these cryptographic walls. Financial systems are critical infrastructure, which is why most engineers in this space rightfully argue that security and stability are paramount. If Bitcoin will be the money of the future, it better be prepared to withstand high-impact, low-probability events.

How thick will these cryptographic walls need to be? Only time will tell. If Bitcoin is able to survive coordinated attacks by multiple state-level attackers, the walls were thick enough.

The End of Mining New Bitcoins

Bootstrapping a new network is difficult. It’s like trying to convince everyone to buy a fax machine if you are the only guy in the world with a fax machine. It’s really, really hard. As outlined above, Satoshi solved this problem by adding a block reward mechanism, which acts as (a) the controlled currency supply of Bitcoin and (b) an incentive for people to participate in the network to expand and secure the public ledger.

Expending energy is essential to provide security for this new financial network.

The current phase of “mining bitcoins”, where miners are incentivized with a high reward, is a clever way to get the network started. In other words: everyone who is greedily mining bitcoins today is helping to bootstrap this new financial system, whether they realize it or not.

John Nash commenting on the game theoretical aspect of Satoshi’s invention.

John Nash commenting on the game theoretical aspect of Satoshi’s invention.

As mentioned above, Bitcoin’s mining difficulty adjusts automatically, leading to a dynamic, self-correcting system. If mining — for whatever reason — gets more expensive, fewer people will mine at a profit, resulting in fewer people mining, lowering the mining difficulty. This, in turn, will make mining easier again and thus cheaper, which will incentivize more people to mine.

Over time, the financial incentive of running a mining operation will change. It follows that Bitcoin’s energy consumption will change as well. The reason why change is inevitable is Bitcoin’s block reward function which ensures a controlled, limited supply.

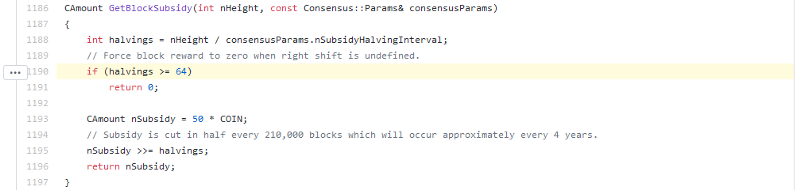

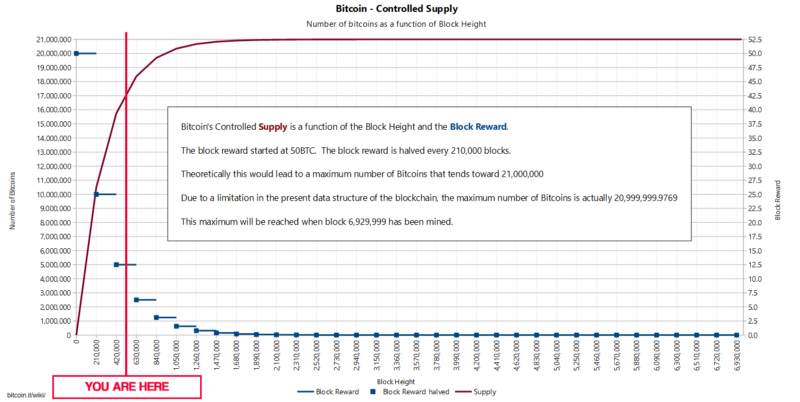

The block reward is halving every 210.000 blocks and will eventually reach zero, after 64 halvings. After the last of these halvings, miners will be left with transaction fees as the only financial reward for mining a new block.

In other words: The “mining of new bitcoins” will eventually stop. The mining of valid blocks will continue after that.

In Bitcoin, code truly is law.

In Bitcoin, code truly is law.

One could argue that we are currently in the bitcoin equivalent of the Gold Rush, where the reward for mining as well as the future projected reward far outstrips the investment and energy costs. While it is hard to estimate how much security is enough security, a case could be made that the Bitcoin network is currently “hypersecured” as a side-effect of this Gold Rush.

Bitcoin’s controlled supply and block reward over time.

Bitcoin’s controlled supply and block reward over time.

We are still in the early phases of Bitcoin’s block reward phase, as the above graph shows.

Whether the adaption of bitcoin as a currency will be slow and steady, or exponential and parabolic, a continued exponential growth of energy consumption is very questionable. I would argue that excessive growth will give way to a somewhat sensible balance between security and energy consumption as the block reward approaches zero. Depending on the future value of bitcoin and the willingness of people to pay transaction fees, this balance might be leaning more towards security or more towards conservative use of energy.

Modern Blocks of Marble

Once you wrap your head around proof-of-work, it becomes more and more clear that the energy consumption of the Bitcoin network is not a bug, it’s a feature. As far as we know, you can’t cheat the laws of thermodynamics. Given that we don’t have any world-shattering breakthroughs in physics, mathematics and/or quantum computing, expending energy is the only way to flip bits, and flipping bits is the only way to mine new blocks.

Unfortunately, we don’t have an intuitive understanding of this new cryptographic world (yet). Fully grasping the importance of proof-of-work requires a deep-dive into a multitude of topics. We lack concise, easy, elegant explanations and metaphors. Hugo Nguyen did a great job explaining how proof-of-work links the abstract, digital world of bitcoin to our physical world:

“By attaching energy to a block, we give it “form”, allowing it to have real weight & consequences in the physical world.”Hugo Nguyen

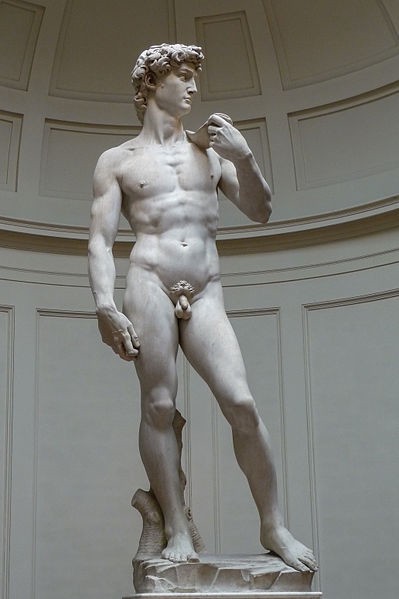

Proof-of-work is essentially a mechanism to easily check the truthfulness of the statement “I worked really hard to create this thing”. From that perspective, our new and fancy computational blocks are a bit like blocks of marble, and proof-of-work is a bit like looking at a beautiful marble statue. It is immediately obvious that a lot of work went into creating the statue. Cheating is extremely hard, because creating such a glorious statue without actually doing the work is pretty much impossible. You can’t throw a block of marble against a wall and everything which is not David will fall off. It’s not impossible, but it is very, very, very unlikely. Instead, you have to chisel away at the marble, and you have to do it properly and with care. One might argue that this is one of the reasons why great artworks are so valuable: a lot of thought, care and work was expended to create them.

Oldschool proof-of-work by Michelangelo. Photo by Jörg Bittner Unna

Oldschool proof-of-work by Michelangelo. Photo by Jörg Bittner Unna

It is similarly unlikely to find valid blocks without actually doing the work. Like an ugly half-haphazardly chiseled statue, an invalid block can be simply thrown away. When you see a valid block, however, you immediately know a lot of work went into it.

In both cases, the artifacts themselves, the statue and the valid block, are in itself the proof of work.

My point is that understanding the nature of proof-of-work and the incentives of mining valid blocks, as well as the security properties and thus the value of proof-of-work, might help to shift the perspective from “energy wasted” to “energy used for creating something valuable”. Most people value beautiful marble statues. A rising number of people value a chain of valid blocks.

Security Through Purity

Another feature disguised as a bug is the randomness of bitcoin’s proof-of-work. A common suggestion for improvement is that we could use all this electricity to do something else, something truly useful, like finding prime numbers or compute protein foldings, in addition to securing the network.

Again, this objection to Bitcoin’s proof-of-work algorithm is rooted in the assumption that finding valid blocks is inherently useless. It is not.

While introducing a secondary reward for doing the work might seem like a good idea, it actually introduces a security risk.

The problem with doing something else — something that other people might consider useful — is that that splits the reward. It means that miners have two reasons for which they are mining.Andreas M. Antonopoulos

Splitting the reward can lead to a situation where “it’s more worthwhile to do the secondary function that it is to do the primary function”. Bitcoin will never have this problem. Bitcoin guarantees its security by the purity of its proof-of-work algorithm.

If someone figures out a more energy-efficient way to secure an open, decentralized, censorship-resistant, permission- and trustless network for value exchange — without compromising one of these qualities — this hypothetical future network will eventually dethrone Bitcoin, solving this supposed energy problem. And no, proof-of-stake is probably not the answer.

In the future, we might find something which is even more suited to be an anchor for truth than energy. Until we do, we should stick to something we are extremely confident in: the laws of thermodynamics; the energy required to do the work in proof-of-work.

Conclusion

I hope to have planted the seed for a shift in perspective: that spending energy on proof-of-work is not a waste, but a worthwhile endeavor.

Understanding mining and proof-of-work in more detail might help to convince some of Bitcoin’s critics and shift the perspective from “inefficient and wasteful” to “secure and censorship-resistant”. Pointing out these nuances might also be helpful to understand that Bitcoin’s energy consumption most strongly correlates with the network’s security, and not with the adoption, usage, or utility of bitcoin. Even if the utility of the network and the price of bitcoin continues to increase exponentially, the energy consumption does not necessarily need to follow the same exponential trend. Gaining a better understanding of the Bitcoin network might also help to understand where other solutions fall short.

Satoshi’s genius was to combine a bunch of clever tricks into a new economic game which creates a digital, scarce artifact, without central issuance. This artifact is backed by computation, and computation requires energy.

The current economic game is a game of walls and vaults, closed systems and centralized power. The new economic game is a game of hashes and blocks, public keys and private keys, based on mathematical proofs and physical reality. A game without gatekeepers, without central authorities, without censorship or discrimination.

The old rules have led to a system where money is valuable “because I say so”, leading to magic tricks like fractional reserve banking, inflation to stimulate excessive consumption, and even hyperinflation because the temptation to print ever more money is simply irresistible.

The new rules might not be easy to understand. They might, however, lead to a new financial reality: a new economy based on sound money. We will all have to adapt to these rules and become familiar with the nuances of this new game. And we will have to come to terms with the fact that a finite resource has to be used to secure this new, decentralized economy. In the case of Bitcoin, this resource is energy.