An Introduction to the Efficient Market Hypothesis for Bitcoiners

| If you find WORDS helpful, Bitcoin donations are unnecessary but appreciated. Our goal is to spread and preserve Bitcoin writings for future generations. Read more. | Make a Donation |

An Introduction to the Efficient Market Hypothesis for Bitcoiners

What the EMH does and does not say

By Nic Carter

Posted January 4, 2020

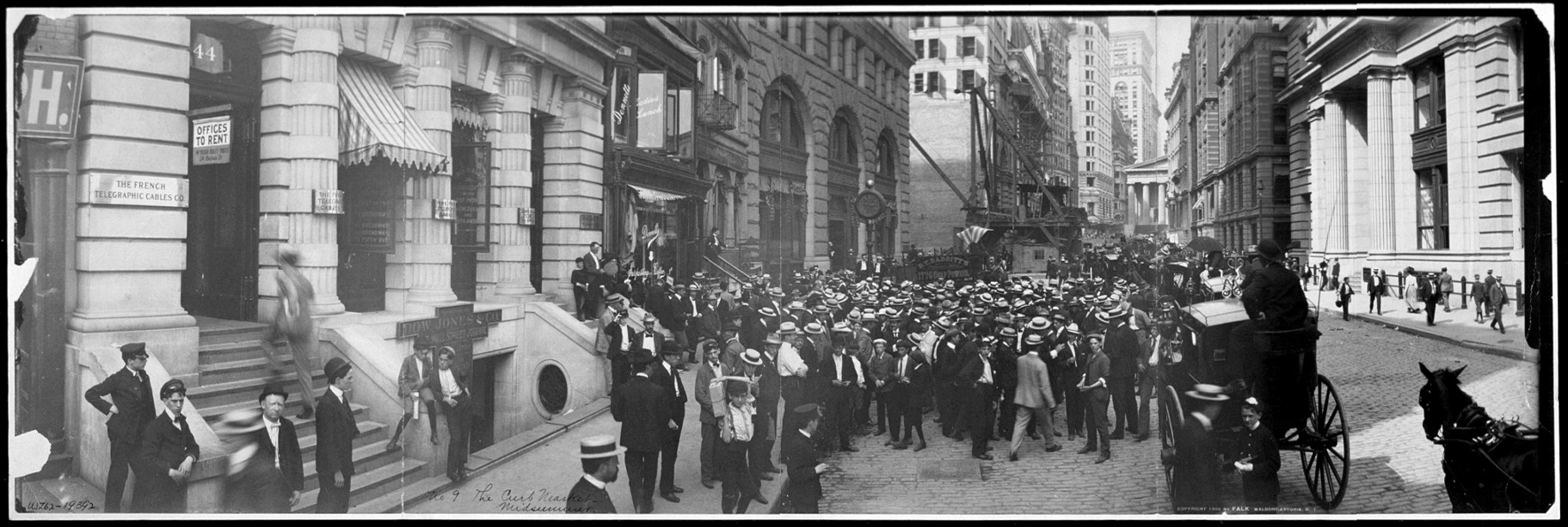

Curbstone brokerage on Broad Street in Manhattan, 1902 (Public domain image from the United States Library of Congress)

As we approach the Bitcoin halving due in May 2020, a heated debate has raged among Bitcoiners about whether the issuance change is being anticipated by the market or not. Those who downplay the purported impact of the issuance change tend to make references to market efficiency. This concept has thus become a source of great rancor and debate. The disagreements are often intractable, as strawman versions of the EMH are presented, and the parties cannot converge on shared definitions. Mutually understood concepts are a prerequisite to a useful debate. Since the concept is widely misunderstood, I thought I’d explain it from scratch, assuming little prior financial knowledge.

Origins of the EMH

The efficient market hypothesis has been attributed to several thinkers, among them Benoit Mandlebröt, Louis Bachelier, Friedrich Hayek, and Paul Samuelson. Hayek’s The Use of Knowledge in Society is useful background reading for the concept, although it never makes reference to the EMH specifically. His seminal essay argues in favor of distributed, market-based economies, in contrast to centrally planned ones. The key insight: markets are information-aggregation mechanisms that no central planner, no matter how skilled or well-resourced, can match. Consider the following passage (emphasis my own):

[T]here is beyond question a body of very important but unorganized knowledge which cannot possibly be called scientific in the sense of knowledge of general rules: the knowledge of the particular circumstances of time and place. It is with respect to this that practically every individual has some advantage over all others because he possesses unique information of which beneficial use might be made, but of which use can be made only if the decisions depending on it are left to him or are made with his active coöperation.

[…] And the shipper who earns his living from using otherwise empty or half-filled journeys of tramp-steamers, or the estate agent whose whole knowledge is almost exclusively one of temporary opportunities, or the arbitrageur who gains from local differences of commodity prices, are all performing eminently useful functions based on special knowledge of circumstances of the fleeting moment not known to others.

In the bolded section you can begin to see how Hayek views markets: as forces that aggregate a multitude of different views and expectations into prices. Hayek understands market-derived prices as information — a particularly high signal source of information at that. The beauty of markets, to Hayek, is that simply by selfishly acting according to their own interests, individuals participating in the economy create signals in the form of prices. The EMH orients this perspective specifically towards financial assets, holding that investors collectively surface relevant information which is incorporated into prices through the mechanism of trades.

Following a series of studies about stock returns like Samuelson’s 1965 Proof that Properly Anticipated Prices Fluctuate Randomly, the EMH was finally codified for good in 1970 by legendary finance academic Eugene Fama (you may have heard of the Fama-French model). In a paper entitled Efficient Capital Markets: A Review of Theory and Empirical Work, Fama defines an efficient market as “a market in which prices always “fully reflect” available information.” If you were stop reading here, you’d already have a better understanding of what is meant by efficient markets than the caricatures presented on Twitter. The EMH is not a mystical claim. It’s simply the view that market prices reflect available information. This is why academics often refer to them as ‘informationally’ efficient markets. The efficiency refers to information proliferation.

What does this actually mean? It simply means that if there is new information which is relevant to the asset being traded, this information tends to be incorporated into the price of that asset with rapidity. And if there are future events which you might reasonably imagine would affect price, they tend to be incorporated into the price when known. Markets don’t wait for (knowable) events to happen — they anticipate them. This means, if a weather forecast predicts that a hurricane will emerge and wipe out sugarcane plantations next week, speculators will bid up the price of sugar today, anticipating the supply shock. Now, of course, when there are unpredictable exogenous shocks (imagine that the hurricane materialized with no warning), then price can only react in real time, as the information becomes known. The speed of information incorporation is one of the tests of efficiency.

While the EMH is a simple idea, it tells us a great deal about how markets operate. Markets are efficient if prices rapidly incorporate new information. Forecastable, market-moving events taking place in the future tend to be incorporated in price beforehand. Importantly, one consequence of the EMH is that, once all relevant information is incorporated into price, you are left with only random fluctuations, called ‘noise’. What this means is that while asset prices will still jitter about, even in the presence of no new fundamental information, these fluctuations contain no information of their own.

And lastly, the difficulty of surfacing unique new information (not already included in price) tends to vary with the sophistication of market participants and the liquidity of the asset. This explains why you might be able to find an edge in an obscure micro cap stock, but probably not in predicting the price of Apple.

Since Fama’s paper, and thanks to popular books on the topic like Burton Malkiel’s A Random Walk Down Wall Street, a heated debate has raged over whether active management is worth it. Indeed, since efficient markets posit that consistent edges are very difficult to find, many investors have come to question whether actively traded vehicles like hedge and mutual funds make sense. In the last decade, trillions of dollars have flowed out of such ‘active,’ stock-picking strategies, and into passive vehicles, which simply seek to track the performance of the entire market, or a specific sector. This is one of the most critical debates happening in finance right now, and it’s mostly due to the growing realization that markets are, indeed, generally efficient.

The EMH described

I take slight exception to the ‘hypothesis’ component of the EMH. If it were up to me, I’d call it the efficient markets model, not hypothesis. This is because it doesn’t really contain a hypothesis. It doesn’t really make a specific testable claim about the world. As stated, the EMH posits that market prices reflect available information (which, as we have noted, is the purpose of markets in the first place). Interestingly, Fama in his 1970 paper calls it the efficient market model, not hypothesis. It seems he has the same intuition.

I would also go as far as to consider EMH somewhat tautological. Recalling Hayek, we know that (free) markets measure society’s net informational stance over various assets. So if we replace ‘market prices’ with ‘concentrated information outputs’ in the EMH construction bolded above, we get the following:

Concentrated information outputs reflect available information

That certainly sounds tautological. But that doesn’t make the model any less useful_._ Conversely, it means that contesting the EMH is to question the nature of markets themselves. And indeed, most critiques of the EMH (I will cover a few later in this piece) generally cover instances where markets are not clearing, for some reason or other. So if you accept that EMH is tautological, ‘efficient markets’ also starts to sound redundant. Indeed, the default state of (free) markets is to be efficient, because this is why we have markets. Markets compensate anyone for finding relevant information. If they weren’t default-efficient, then we wouldn’t bother with them.

Referring to it as a model makes it very clear that it’s just an abstraction of the world, a description of the way markets should (and generally do) work, but by no means an iron law. It’s just a useful way to think about markets.

Let me be clear! I do not believe in the “strong form” of the EMH. No finance professional I know does. It is generally a straw man. The strong form holds that markets reflect all information, all the time. If this were true, no hedge funds or active managers would exist. No one would bother poring over Apple’s quarterly reports, or evaluating the prospects for oil discovery in the Permian basin. Clearly, given that we have a large active asset management industry, in which lots of very bright individuals constantly seek to surface new information about various assets, the strong form doesn’t hold.

Truthfully, the EMH is not something you ‘believe in,’ or not. The choice is to understand markets as useful information-discovery mechanisms, or reject the usefulness of markets altogether.

There are of course conditions which lead to market inefficiency. Fama acknowledges as much in his 1970 paper, calling out transaction costs, the costs of acquiring relevant information, and disagreement among investors as potential impairments to market efficiency. I’ll discuss two here: the costs of surfacing material information, and frictions inherent in actually expressing market views.

If the EMH generally holds, how are funds compensated for finding information?

So what explains the fact that there is a large (albeit shrinking) industry involved in active investing, despite the fact that markets are generally efficient? If market-relevant information is generally encoded in prices, then there is no profit from finding new information and trading against it. But clearly, many individuals and firms do actively attempt to surface new information. This presents a bit of a paradox.

This brings us to another one of my favorite papers, On the Impossibility of Efficient Markets, by Grossman and Stiglitz. The authors point out that gathering information is costly, not free. They then note that since EMH posits that all information is immediately expressed in prices, there would be no compensation from incurring costs to surface new information under that model. Thus markets cannot be perfectly efficient: information asymmetries must exist, as there must be a way to compensate informed traders. Their model introduces the useful variable of information cost into the standard model of market efficiency. It follows from their model that if information becomes more costly, markets become less efficient, and vice versa. So whether or not markets reflect their fundamentals is at least partially a function of the difficulty of surfacing that relevant information.

The authors conclude:

We have argued that because information is costly, prices cannot perfectly reflect the information which is available, since if it did, those who spent resources to obtain it would receive no compensation. There is a fundamental conflict between the efficiency with which markets spread information and the incentives to acquire information.

A rather delightful implication of Grossman and Stiglitz is that, to render arbitraging prices back to where they ‘should’ be a profitable activity, there has to be a cohort of traders who are perennially knocking prices out of whack. Fischer Black (he of the Black Scholes formula) gives us an answer, with a lovely paper pithily entitled Noise in the Journal of Finance. He identifies unsophisticated ‘noise’ traders: those who trade on noise, rather than information. Noise can be found anywhere. Just mosey on to Tradingview and see the plethora of indicators that people swear by. Black divides market players into two cohorts:

People who trade on noise are willing to trade even though from an objective point of view they would be better off not trading. Perhaps they think the noise they are trading on is information. Or perhaps they just like to trade.

With a lot of noise traders in the market, it now pays for those with information to trade. Most of the time, the noise traders as a group will lose money by trading, while information traders as a group will make money.

Noise, in Black’s view, “makes financial markets possible.” The existence of noise traders gives professional firms like hedge funds liquidity, and valuable counterparts to trade against. In the poker analogy, noise traders are the fish. They make the game profitable for the sharks, even in the presence of a rake. Ask any former online poker player — as the scene became more competitive, and unsophisticated players left, it stopped being as profitable to play.

The noise theory resolves the ‘apparent impossibility’ of efficient markets as pointed out by Grossman and Stiglitz. The existence of noise as introduced by unsophisticated traders gives sophisticated traders a considerable financial incentive to introduce information into prices. So you can thank the degens overtrading on Bitmex — they are the ones compensating funds for allocating resources to Bitcoin and surfacing relevant information quickly.

If the EMH generally holds, how do you explain instances where markets do not clear?

This is another good question. There are copious examples of situations where arbitrage opportunities were easy to identify, yet where the arbitrage could not be closed for some reason. The most famous of these examples is arguably the trade which caused the demise of Long Term Capital Management. It was a pair trade on bonds which were effectively identical but were differently priced (partially due to the Russian default in 1998). LTCM was betting that the prices of the bonds would converge. However, many other hedge funds had made that same bet with leverage, and as the bonds failed to converge in a timely manner, LPs in some of the hedge funds redeemed, the funds faced margin calls, and were thus forced to liquidate this positions. This kicked off a feedback loop causing additional squeezes: the cheaper bonds were sold off, and the pricier instruments kept rallying as shorts were covered. LTCM was betting on market efficiency and the convergence of these instruments; but because of market stress and the winding down of pent-up leverage, they weren’t able to complete the trade, and the fund blew up.

This phenomenon is examined in a 1997 paper from Shleifer and Vishny entitled The Limits of Arbitrage. Shleifer and Vishny point out that arbitrage is not normally done by the market, generically, but rather is a task delegated to specialized institutions (funds, typically). As such, arbitrage is costly: requiring freely available capital. There’s a paradox: great arbitrage opportunities come about when the market is under stress (this is when you get many stocks trading at a low price-to-book, for instance). But during times of market stress, capital is least available. Thus the arbitrageurs, who require capital to operate, are worst equipped to perform the required arbitrage when they are most needed. These are the limits of arbitrage. As the authors state:

When arbitrage requires capital, arbitrageurs can become most constrained when they have the best opportunities, i.e., when the mispricing they have bet against gets even worse. Moreover, the fear of this scenario would make them more cautious when they put on their initial trades, and hence less effective in bringing about market efficiency.

Take the simple example of a value-based hedge fund which has raised outside capital. They will tell LPs (investors in the hedge fund) of their intention to pursue contrarian bets — buying value stocks when they are cheap, for instance. Let’s say the market declines and they buy a basket of stocks whose valuations have contracted and have low P/E ratios. However, imagine that the market subsequently declines another 40%. Their LPs are now staring at a loss and ask to redeem. This is the worst possible time: the fund has to sell the stocks at a loss, even if they have a high conviction on making money on them in the long term. They would much rather be buying the (now very discounted) stocks, whose valuations are even more attractive. To make things worse, liquidating those positions forces them down further, punishing other funds making the same trade.

Shleifer and Vishny therefore find that:

[P]erformance‐based arbitrage is particularly ineffective in extreme circumstances, where prices are significantly out of line and arbitrageurs are fully invested. In these circumstances, arbitrageurs might bail out of the market when their participation is most needed.

The limits to arbitrage caveat about EMH actually explains a lot of situations where people will describe market conditions and lament that information is not being incorporated. This is often taken as a slight against the EMH. But of course we cannot expect malfunctioning markets to operate properly. So when Dentacoin’s multi-billion dollar putative market cap is touted as an example of market efficiency not holding, consider that it likely had a minuscule float, ownership was extremely concentrated, and obtaining a borrow for a short was impossible. This means that market participants cannot meaningfully express their views on the asset.

A fuller conception

Mindful of these constraints (issues of market structure, costly information, limits to arbitrage), we can devise a more complete version of the EMH which includes these caveats. You might therefore devise a modified EMH that sounds a bit like this:

Free markets reflect available information to the extent that price-setting entities are willing and mechanically able to act upon it.

- Free markets: because state-controlled markets may not clear (for instance, markets for currencies with capital controls do not give reliable signals, since selling is effectively constrained)

- Price-setting entities: because minnows don’t ultimately matter most of the time. A small number of well-capitalized participants can suffice to incorporate material information into price

- To the extent that they are willing: this covers the ‘costly information’ caveat. If information is more costly to obtain than it is worth to instrumentalize (for instance, in the case of discovering accounting fraud in a micro-cap stock), then it won’t be included in price

- Mechanically able: this covers cases where limits to arbitrage exist. If there is a liquidity crisis, or the markets are not functioning properly, for whatever reason, and funds cannot operationalize their views on the market, inefficiency may occur

So when most financial professionals talk about the EMH, they generally imply a modified, slightly caveated version like the one above. Almost never do they mean the ‘strong form’ of the EMH.

Interestingly, by caveating the EMH, we have stumbled on an alternative conception entirely. The model I have described here somewhat resembles Andrew Lo’s adaptive market hypothesis. Indeed, while I am very happy to maintain that most (liquid) markets are efficient, most of the time, the adaptive market model far more closely captures my views on the markets than any of the generic EMH formulations. Many active managers that I know are at least familiar with Lo’s work. The theory is fully developed in his book, but you can get a condensed version in his 2004 paper.

In short, Lo attempts to harmonize findings from behavioral economics finding apparent irrationality on the part of investors, with the orthodox EMH school. He calls it the adaptive market hypothesis because he relies on an evolutionary approach to markets. Taking Black’s insight further, Lo divides market participants into ‘species’, giving us a view of market efficiency which departs from the mainstream:

Prices reflect as much information as dictated by the combination of environmental conditions and the number and nature of “species” in the economy or, to use the appropriate biological term, the ecology.

Lo describes profit opportunities from information asymmetries as ‘resources’, leading to formulations like the following:

If multiple species (or the members of a single highly populous species) are competing for rather scarce resources within a single market, that market is likely to be highly efficient, e.g., the market for 10-Year US Treasury Notes, which reflects most relevant information very quickly indeed. If, on the other hand, a small number of species are competing for rather abundant resources in a given market, that market will be less efficient, e.g., the market for oil paintings from the Italian Renaissance.

The contextualism and pragmatism that Lo’s model presents aligns it with the experience of most traders, who intuitively understand that market participants are quite heterogeneous, and understand the notion of ‘table selection’ (borrowed from poker). I won’t dive too deep into Lo’s take here, but I do recommend his book, and at the very least his paper summarizing his theory.

What this means for Bitcoin and the halving

As we have seen, most markets are efficient most of the time. This is not something markets just happen to do; this is their purpose. I have discussed a few exceptions: the limits to arbitrage situation, non-free market situations, situations where behavioral biases apply, and situations where market participants may not be sufficiently motivated to surface relevant information. The question is, do any of these conditions apply to the Bitcoin markets? Right now, this doesn’t seem to be the case. We are not in a liquidity crunch. There are no apparent limits to arbitrage. In the pre-financialized era for Bitcoin (I’d say anytime before 2015), you could have convincingly made that case. There truly was no easy way for a well-capitalized entity to express as positive view on Bitcoin. But today there is.

As for free markets, Bitcoin is clearly a very free market, one of the freest on earth (since the asset itself is highly portable and easily concealable, and traded around the globe). Unlike most currencies, it is not backed or guaranteed by a sovereign, and there are no capital controls impairing selling. Participants also have the abundant ability to place large short positions on Bitcoin, so they can express a diverse set of views. So we can check the ‘functioning markets box’. Now, is Bitcoin sufficiently large for there to be a significant number of sophisticated funds devoting concerted effort to surfacing material information? At a $150b market cap, I think that’s absolutely the case. The final test of market efficiency is whether or not market-moving information is incorporated into prices right away, or with a lag. An event study covering the effect of exogenous shocks like exchange hacks or sudden regulatory shifts on price would be welcome.

The only necessary conditions for efficiency for which Bitcoin still has question marks have to do with disagreement among market participants (i.e. the lack of a shared valuation model that price setting entities converge on), and the development of more financial plumbing. There are still a few classes of entity for which Bitcoin exposure is rather difficult to obtain. Of course, surmounting these challenges will render Bitcoin’s prospects sunnier.

So is the halving “priced in” or will it be a catalyst for appreciation? If you’ve read this far, you will understand that I consider it patently absurd that a change in issuance would have been overlooked by the price-setting entities. Anyone with an interest in Bitcoin has been aware of the supply trajectory from inception. Supply was encoded in the very first implementation that Satoshi released to the world in January 2009. Long-scheduled changes in the rate of issuance do not constitute new information. Any presumed demand-side reactions to the ‘halving catalyst’ can also be anticipated by sophisticated funds who have a strong incentive to frontrun investor optimism.

Now, can Bitcoin appreciate from here onwards? Absolutely. I don’t believe appreciation, if it occurs, will be due to the entirely foreseeable changes in the rate of issuance (the forthcoming halving will take us from 3.6% to 1.8% annualized issuance), but of course I feel that there are other factors which could positively affect the price, most of which are hard to predict. Is that consistent with the EMH? Very much so. EMH permits informational shocks (for instance, imagine if we suddenly had rampant inflation in a major world currency). It’s also possible that the price setting entities are taking an overly conservative view of Bitcoin’s future, or that they are acting on a weak fundamental model. These are consistent with weak form EMH.

I’ll leave you with this parting thought. Regulated securities markets have structural barriers to efficiency in the form of prohibitions on insider trading. As Matt Levine likes to say, insider trading is a form of theft in which someone trades on information which does not belong to them. They have not discovered the information from public sources, but rather were privy to something like a merger discussion and acted on it. Since insider trading is banned, stock prices generally don’t reflect pending catalysts like acquisitions until they are publicly announced. However, in a market for a virtual commodity like Bitcoin, insider standards don’t typically apply. If a catastrophic bug is found, you can expect that this information might be incorporated into price right away. So in that sense, it’s quite possible that the market for Bitcoin is more informationally efficient than markets for U.S. equity are.

Common objections

I will consider some objections here. Odds are, your responses are covered.

I found an instance of inefficiency. This is evidence for the inefficiency of markets generally

This is a bit like throwing a baseball in the air and claiming that its temporary departure from the earth disproves gravity. Few or no finance practitioners believe that all markets are efficient all the time. If information is unevenly distributed, or information-owners lack the means to instrumentalize their views, then the prices may not reflect information. Short term instances in which markets do not apparently reflect information are just invitations to query why market participants were unable to price in relevant information. These failures aren’t evidence of the weakness of the EMH, but rather reinforce its usefulness as an explanatory tool.

Behavioral biases exist, so market efficiency doesn’t hold

A number of persistent behavioral biases have indeed been found by researchers, and I find it plausible that they systematically affect asset prices to an extent in the medium term. However the question here is whether they are relevant to the matter at hand — the putative effect of a change of the rate of supply on the price of the asset — and whether these purported biases can actually affect the price formation of a highly liquid $150b asset. You might respond: ‘well Bitcoiners have a bias which causes them to bid up the price of assets with sharply decreasing issuance rates, even if this information is already known.’ If you can prove, Kahneman and Tversky-style, that this is a universal human bias which affects asset pricing, and contradicts dominant market models, not only will you win the argument, but you will also likely collect a Nobel. In this situation I’d also refer you once again to Lo’s adaptive markets.

Efficiency is impossible in Bitcoin because there are no fundamentals

Some people hold that sentiment drives everything in crypto markets, and that fundamentals do not exist. This is a convenient fallacy. There are obvious fundamentals which everyone would agree matter. Here is a short, non-exhaustive list:

- the quality of financial infrastructure enabling individuals to get exposure to and hold Bitcoin. In 2010, it was virtually impossible to buy Bitcoin, and your only option for custody was the Bitcoin QT ‘Satoshi Client’ or a homebrewed paper wallet. Today, you can get a billion dollars of Bitcoin exposure, and you can self-custody it or rely on some of the world’s largest asset managers and custodians. This is a fundamental change

- the quality of the Bitcoin software (compare the current version with Satoshi’s first client). The protocol itself and the tooling surrounding it has been improved, refined, and made more useful

- the actual stability and functionality of the system — imagine a case where Bitcoin failed to produce blocks for a month. That would surely impair the price. If you concede this, you admit that there are ‘fundamentals’ beyond mere sentiment

- the number of individuals globally that are aware of and demand Bitcoin. This is ‘adoption’. This not mere sentiment; this is a measure of which sources of capital, worldwide, are actively seeking exposure to Bitcoin

There are many other fundamentals which I won’t cover here. Funds which trade Bitcoin seek to track the trajectory of these variables, and ascertain whether Bitcoin is too richly or modestly priced relative to their growth. This is “fundamental analysis”.

Again, if you aren’t persuaded, just think about the contrast between Bitcoin’s state in 2010 and its state in 2020. It’s many orders of magnitudes easier to use, acquire, buy, sell, and store. That is a change in fundamentals. Granted, these aren’t ‘fundamentals’ of the sort that apply to stocks with cash flows, but Bitcoin isn’t a stock. A unit of Bitcoin is a claim on ledger space which gives you access to the particular transactional utility of the network. I’ll concede that the fundamentals aren’t quite as explicit as those present in a stock. But, the notion of ‘fundamentals’ isn’t just restricted to equity or instruments with cashflows. Global macro investors consider currencies based on macro variables or assessments of political risk. Commodity traders look at production rates and the ebb and flow of supply. There are analogies here.

All of this to say that funds have meaningful market-relevant information to trade against, not just sentiment or hype. It’s just that it’s hard to obtain a precise fundamental assessment of Bitcoin.

Efficiency is impossible in Bitcoin because it is volatile

It’s entirely possible to have volatile and efficient markets. Recall that all efficiency requires is that available information is incorporated in price. Think about the value of a call option close to expiry, with the underlying fluctuating around the strike price. One minute the option is in the money, the next it is worthless. This would be both a volatile and efficient situation.

Alternatively, consider the value of Argentine government bonds in response to political turmoil. The fundamental here is the Argentine government’s willingness to honor their debts. Efficiently functioning markets would continuously reevaluate the prospects for creditors being repaid. In a period of flux the fundamental is volatile, and so too consequently is the value of the bonds.

Bitcoin’s volatility derives in part from market participants rapidly re-assessing its prospects growth, both in terms of pace and trajectory. Even small changes in future expectations of growth rates have significant effects on the implied present value. (Indeed, in DCF models for equity valuation, the outputs are very sensitive to long term growth rates.) Market participants revise their growth expectations frequently, and expectations differ (because there is no single dominant model of Bitcoin’s price), giving rise to the elevated volatility (especially against the backdrop of a inelastic supply). If future expectations of growth are the fundamental, then the rapid revaluation of those expectations creates consequent volatility in price. So volatility does not disqualify efficiency.

If the EMH were true, Bitcoin would have just started life at its current valuation

This isn’t how the world works. As I explained above, Bitcoin didn’t start life with mature, rock solid fundamentals like it presently has. It had to grow into its valuation. In its earliest days, there was considerable uncertainty over whether it would achieve any success whatsoever. It had to actually go through all these trials and tribulations to get to where it is today. So it wouldn’t have made sense for large funds to allocate to Bitcoin on day 1 (although, it clearly makes sense in hindsight), because they didn’t know it would grow, and in many cases, because they structurally couldn’t invest in it. Think about how you would have acquired Bitcoin in 2012, two years into its existence. You would have had to use something like Charlie Shrem’s BitInstant, or the (already insolvent) Mt Gox, which we know now was run shambolically. You could have mined Bitcoin, but this was a difficult and deeply technical task.

This returns us to the “limits to arbitrage” point. Many investors that wanted to buy Bitcoin from 2009 through to present day simply couldn’t, due to regulatory reasons, operational risks, and a lack of functional market infrastructure. Even if they did believe that Bitcoin would be worth north of $100b at some point, they wouldn’t have had the ability to instrumentalize that view. Moreover, investors didn’t start out with rock solid conviction. They needed to see Bitcoin work, successfully, in the wild, without being shut down, before choosing to store wealth in it. If you believe that Bitcoin’s continued success represents new information being brought to market, then you understand that the EMH does not require it emerging from the womb, fully formed, at an initial >$100b valuation.

Something which is influenced by ponzi-related buying like Plustoken cannot be efficient

I’d agree that investors in Plustoken buying (and then selling) about 200,000 BTC was a major driver of price action in 2019. However, this doesn’t impair efficiency. If it had been known in the West that Plustoken had all those coins, and were just about to sell them off, and the price of Bitcoin did not move, then I agree — there would have been questions about efficiency. However, it wasn’t until much later, after much of the coins had been sold off, that information percolated through the West about the Plustoken BTC. Remember, efficiency doesn’t require that prices never move; rather, it suggests that prices move on new information.

Small cap assets pump on by hundreds of percent on dubious news. This is evidence of market inefficiency and disproves the EMH

Again, local, or temporal evidence of perceived irrationality does not invalidate the EMH. You either believe markets are good information clearing mechanisms or you do not. Granted, many of these small cap altcoin markets are very poor, from a structural perspective. These assets may trade on unregulated or illiquid exchanges. This means the prices you see do not necessarily reflect reality. Thus temporary pumps and dumps in illiquid assets don’t prove much in either direction, aside from the poverty of the market environment in which they trade.

Generally speaking, most adherents to the EMH will concede that efficiency varies positively with the size of the asset and the sophistication of the participants. It will be very hard to find an edge in large, publicly traded stocks. Odds are, if you find some market-relevant information about Apple or Microsoft, someone else will have found it as well. But in smaller, less liquid asset classes, the returns from surfacing relevant information are far less, so there are less analysts actively inserting information into assets, meaning that opportunities may well exist. This is because large, multibillion dollar funds simply cannot operationalize strategies trading in microcap assets.

This is simply to say that there are scale effects with efficiency. Bitcoin is not a microcap; it’s a globally traded traded asset worth over $100b. This ensures that there are high returns from surfacing relevant information and expressing it in the form of trades. Thus there is a significant disanalogy between the inefficient microcap altcoins (where returns from finding information are low, and markets are weak), and a mature asset with lots of analysts looking for an edge.

When small cap cryptoassets get 51% attacked or suffer bad news, they don’t decline. This demonstrates that crypto markets are not efficient

I’ll defer to Lo here (seriously — read Adaptive Markets!). The adaptive explanation would be that small cap assets are generally held by hardcore believers, or better yet, closely held by confederates of the founding team. In those conditions, cartel-like behavior can easily emerge. You have likely seen these conversations on Reddit and Telegram: coin owners urging each other not to sell, especially not in the presence of bad news, since the crypto community is briefly paying attention to the project. Renewed buying in the face of bad news is a way that issuers seek to blunt the effect of a negative catalyst. This only works in small markets were ownership is not widely distributed, though.

Also, it’s worth considering that virtually no one holds these assets because they like the underlying technology or find that particular flavor of code ripped off from Bitcoin Core or Ethereum that interesting. Small cap cryptoassets are held in expectation of a possible future pumps. Thus, impairments relating to the actual protocol itself are not the fundamental. The fundamental is the issuing team’s willingness to procure “adoption,” or at the very least, feign adoption by securing favorable press releases and partnerships. As long as the underlying protocol doesn’t totally dissolve, the ‘fundamental’ — the ability of the issuing team to create hype — can remain intact.

Since some bitcoiners mechanically buy Bitcoin on a regular basis (think: tithing) and less new supply will exist, this will mechanically cause appreciation

This is an example of first order thinking. The EMH lives on the second order. The key insight of the EMH, to me, is that any information you have, a sophisticated market participant also has. Since sophisticated market participants are strongly incentivized to find relevant information and trade against it, you can bet that they will have expressed that information the moment they acquired it. If this were indeed a plausible hypothesis (that static buying pressure would have a positive effect on price as issuance is cut in half), then these funds have already expressed this positive view in the form of a trade. This is what is meant by “priced in.” If something material is discovered to be due to happen tomorrow, it will be incorporated into price today. This is one of the most tricky features of the EMH, and it genuinely takes a bit of effort to get your head around it.

The question then becomes, not “is this information which, in a vacuum, would move the price?” but rather “do I have information which the smartest and best-resourced hedge fund analyst does not have?” If the answer is “no,” you can expect that this information is presently incorporated into price (to the extent that it is actually material information).

Why the focus on funds? The reason is that they are specialized firms which aggressively seek out information and express it in the form of trades. They are the entities which keep price in line with the “fundamental.” You need to recall that you are not operating in isolation. You are operating in the digital equivalent of a jungle with predators lurking around every corner. These predators are skilled, fast, and well resourced.

In equity markets, we’re talking about funds that have personal relationships with CEOs and CFOs, have dinner with them, and interpret whether they are optimistic about the next quarter. Funds that have dozens of analysts crunching datasets you weren’t even aware existed. They will track corporate private jet movements to suss out whether an acquisition is likely to take place. They will run a machine learning model to assess the emotional state of Jerome Powell from his eyebrow twitches as he announces Federal reserve actions. They will take satellite data imagery from parking lots to predict whether Walmart will beat quarterly earnings guidance. Public markets are incredibly competitive. They are where some of the most talented individuals make their careers, and there’s no real restriction on being able to act on information (outside of insider trading). Anyone who believes they have an edge is free to express their view in a trade.

So if you feel you have information which is market-relevant (like this expectation that a supply contraction would drive up the price), the most sophisticated participants have it too. And they’ve already evaluated it and acted on it.

Additionally, you need to recall that markets are not democratic. They are weighted by capital. A whale can express a far stronger opinion than a minnow. Hedge funds simply have more capital (and they tend to have access to cheaper leverage!). Then, when they develop a view on some stock, they have the means to express that view. This is how the “pricing in” takes place. Thus it’s really only price-setting entities that matter most of the time.

Plustoken amassing 200k BTC (~1% of supply) and selling it was a major driver of price action in 2019. Why wouldn’t the halving (affecting 1.8% of issuance) do the same?

First of all, the rise and fall of Plustoken wasn’t anticipated. It was genuinely new information — so much so that most investors only learned of the magnitude of the ponzi until after it was mostly done selling off. Also, as far as we can tell, the Plustoken BTC wallets were liquidated over a relatively short period; about 1–2 months far as I can tell. That’s a lot of BTC for any market to absorb. The change in issuance adds up to a decline in 1.8% annualized — but that’s annualized. What it means mechanically is that ~24,800 fewer BTC will be mined every month. That’s a large number, but it’s not the same as 200,000 BTC being liquidated in a short period. And, unlike Plustoken, the reduction is known well in advance.

The halving will affect Bitcoin from the demand side, by causing excitement among investors and getting press coverage. Thus the halving will still be a positive catalyst for Bitcoin

The same logic as found in the response directly above holds here. If you look at the Litecoin case study, the price was clearly bid up in anticipation of the halving, and then it collapsed after the halving itself. This may well have been a case of investors hoping that the halving would be a positive catalyst. You can see how investors positioning themselves (making bets on how they think other investors might react) affects price. You get into a recursive game where everyone is watching everyone else, and they all try and anticipate what the other is doing. Thus even if there is a highly-anticipated demand-side shock on the date of the halving (either through press coverage or simply investor ebullience), it will have been anticipated by a price setting entity and likely incorporated into price months prior.

If markets are efficient, there’s no point investing in Bitcoin

This isn’t the case at all. There are some informational facets of Bitcoin which are entirely known and transparent, like the supply schedule. However, as I mention above, a lot of the fundamental drivers of the Bitcoin price are not easily quantifiable or even knowable. No one quite knows how many Bitcoin owners there are worldwide, for instance. If you are able to forecast these factors better than others, you will be able to find an edge. Additionally, there are plenty of un-forecastable shocks which might have a positive effect on Bitcoin in the future, such as currency crises. Critics of the EMH fail to see that it only stipulates that markets express available information. Obviously, unknown future catalysts are not available. They haven’t happened yet.

Ultimately, if you are better at forecasting Bitcoin’s growth than other price-setting entities, you might want to trade on your superior knowledge. I think this is an entirely plausible prospect. So I am absolutely not discounting Bitcoin potentially being attractive for an active allocator, even in the presence of the EMH. Indeed, I personally have a positive outlook on Bitcoin. So clearly I believe there is alpha in having specific domain expertise on Bitcoin. If I were a staunch strong-form EMH believer, I wouldn’t be in active management! In fact, active managers have a very strong incentive to find ways to repudiate the EMH. So it should be rather telling that I am defending it here.

For an example of what a demand-oriented fundamental model of Bitcoin might look like, here’s an attempt courtesy of Byrne Hobart:

Investing in Bitcoin: The Asset Allocator’s Perspective

Off and on, friends ask me why I’m not working at or running a crypto hedge fund. I’m interested, worked in the…

medium.com

Under the presence of weak-form EMH, fundamental analysis is possible, and indeed necessary. After all, someone has to do the analysis to surface the information that ultimately is expressed in prices. This job is left to active managers. So maybe those nasty hedge fund investors are useful for something, after all.

Thanks to Allen Farrington and Leigh Cuen for their helpful review and feedback.