The Return of the Deniers and the Revenge of Patoshi

| If you find WORDS helpful, Bitcoin donations are unnecessary but appreciated. Our goal is to spread and preserve Bitcoin writings for future generations. Read more. | Make a Donation |

The Return of the Deniers and the Revenge of Patoshi

By Sergio Demian Lerner

Posted April 16, 2019

Synopsis: In this article I will discuss what we know about the early Bitcoin blocks. Also I will present a new strong argument that a single miner mined 22k blocks. Finally I’ll introduce satoshiblocks.info, new website that shows a cool visualization of early blocks.

The last time I wrote about Satoshi I thought it would be the last. But here I am, again. Let me bring some context. It all began in a discussion in 2013, in bitcointalk forum, where a plausible reasoning led me to believe that Satoshi would have mined one million bitcoins during 2009-2010. As you know, plausive reasoning doesn’t let you prove anything mathematically, however it gives incredibly good results when applied correctly to solving real real-world problems, where information is imperfect or missing. The original argument about Satoshi coins can be simply stated like this: Supposition: Anyone who took the time and effort to create Bitcoin would not risk letting the network to halt due to lack of miners. He would run at least a miner himself. During 2009 the mining activity was so low that it was kept active on the minimum accepted difficulty, and blocks were created at a lower rate than one every 10 minutes. It’s plausible that even if Satoshi wanted to turn off his miner after a while, he may have finally decided to let it run until seeing more activity.

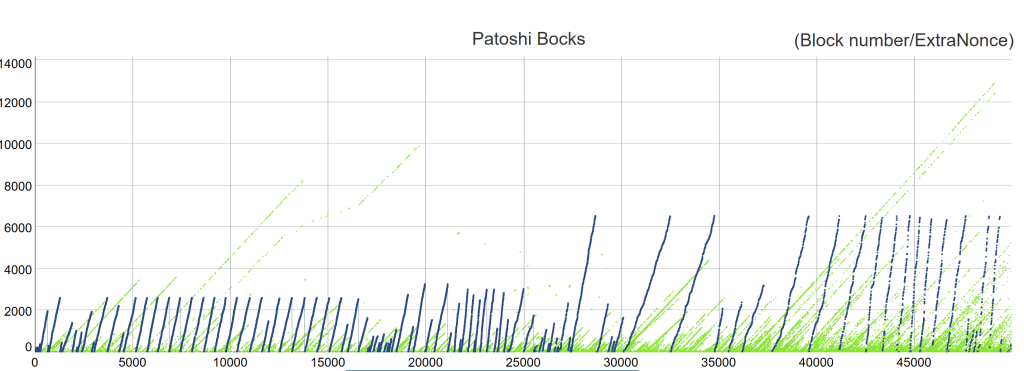

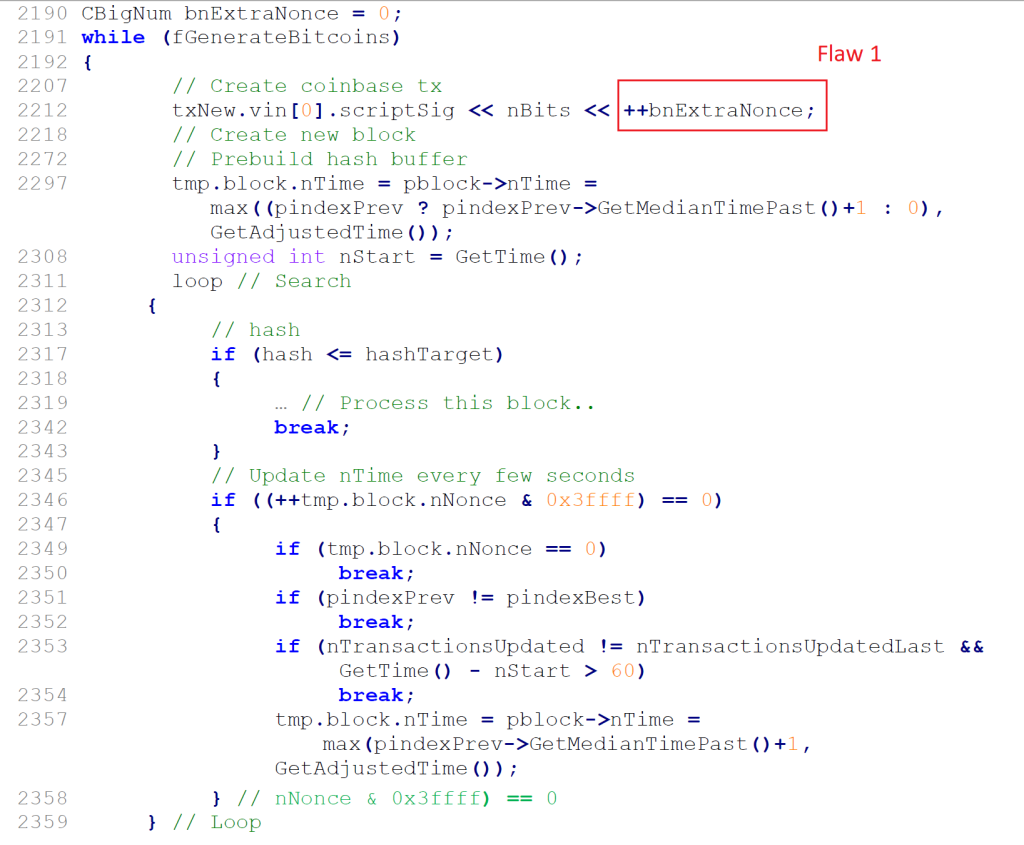

The Patoshi Pattern

In March 2013 I was able to turn the plausible reasoning into a probabilistically falsifiable argument, which means it it’s highly improbable to be false. By reading the original Satoshi client v0.1 source code, I discovered three privacy-related flaws that, together, enable anyone to correlate the blocks mined during the first years and uncover a common origin. Also, it allows anyone to compute the approximate mining hash rate of each of the early miners. If one of these flaws had been absent, it would not have been possible to recognize a very special miner track and the tracks of the remaining miners. But first, a little technical background. The ExtraNonce field, located in the coinbase transaction, increments every time the nonce fields overflows, meaning the search space is exhausted. As the nonce field is 32 bits in length, and the Bitcoin initial difficulty was tuned to require scanning 32 bits on average, the nonce would sometimes, but not always, overflow. Now let’s present the three flaws present in the original Bitcoin code:

- The ExtraNonce works as a “free running counter”, without resetting to zero between blocks mined.

- The rate a certain miner increments the ExtraNonce is much faster than its actual hashrate would indicate, based on the original Bitcoin source code. We’ll call this miner Patoshi.

- Every few seconds during mining, the best block is checked. If the best block changes, the ExtraNonce is additionally incremented. Normally every external block received will increment the ExtraNonce, except for the exceptional miner Patoshi, which doesn’t seem to follow this rule.

Together these flaws enable the visualization of the Patoshi Pattern. Blocks in the Patoshi pattern will be elements of the Patoshi set (or P set).

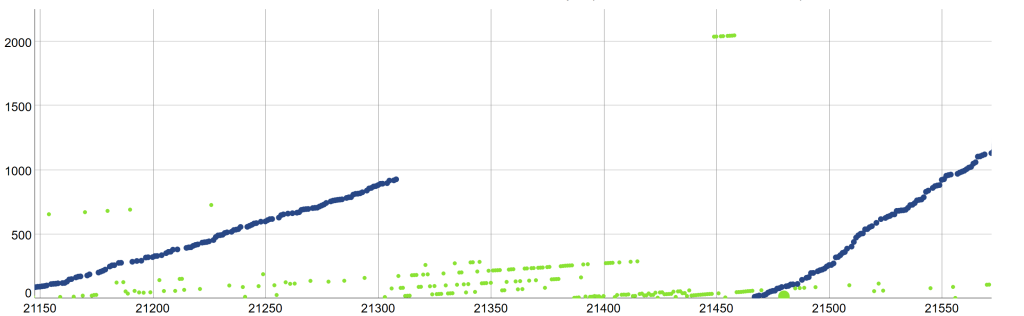

The Patoshi Pattern (blue) and the Remaining Miners Patterns (green)

The Patoshi Pattern (blue) and the Remaining Miners Patterns (green)

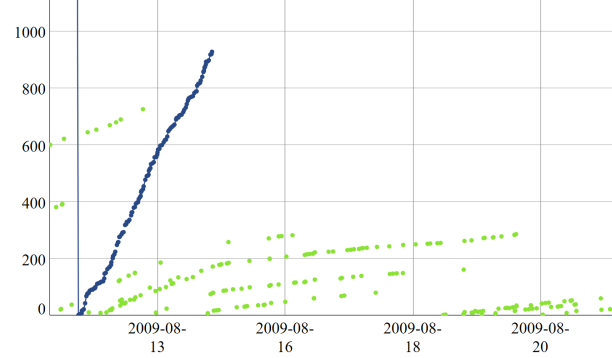

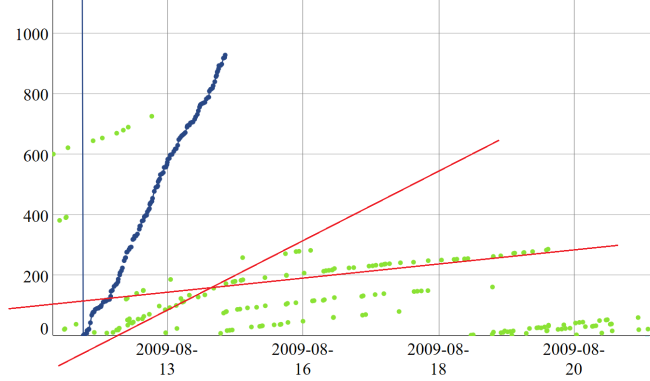

The first flaw is that the ExtraNonce field was handled in a non-privacy preserving way. By not being reset each time a new block is mined, it works as a free-run counter or timestamp.

The second is that for a reason that was only uncovered a year later, the rate this timestamp is incremented by Patoshi was higher than the number of blocks solved would suggest, so even if his mining equipment was not so much faster, it looked so. This flaw alone let you very easily separate Patoshi from the rest of the miners. We lack information about how Patoshi mining software operated: for instance, it’s seems that the Patoshi miner didn’t followed the rule in flaw 3, but it can be the case that it checked the change in the best block less frequently and this invalidates any attempt to measure if flaw 3 was present or not in his software.

The third flaw enables anyone to follow the tracks of the remaining miners. If this flaw had not been present, most blocks of the remaining miners would be indistinguishable from “noise”, having ExtraNonce values that are too close to zero, because the ExtraNonce would hardly ever increment. The nonce values of the remaining miners almost never overflow. In fact, because of this, in the blocks of the remaining miners the ExtraNonce counter behaves more like a global block counter, and therefore the ExtraNonce patterns of different miners appear with similar slope. If two blocks A and B are mined by the same miner, then the ExtraNonce delta between them would almost equal to the number of blocks mined between A and B. The moment in which the miner starts mining from a zero ExtraNonce value establishes a unique point the in the line created by every non-Patoshi miner.

When Patoshi stops mining, the remaining miners increment the ExtraNonce at a lower rate due to privacy flaw 3.

When Patoshi stops mining, the remaining miners increment the ExtraNonce at a lower rate due to privacy flaw 3.

An exceptional case is when several blocks are mined in a very short time: or if the mining process is paused and resumed after a few minutes, then the ExtraNonce will be incremented only once for many blocks in a row. However, this doesn’t seem to happen often. Last, it seems that the Patoshi miner doesn’t follow this rule: there are many cases where the distance between his blocks is lower than the number of blocks in-between. While the absence of this flaw is yet another way of distinguishing Patoshi blocks from the rest, we’ll focus on other more interesting distinguishers.

Together, the 3 privacy flaws enable the ExtraNonce in early blocks “links to” the last block mined by the same miner, for all miners. This link is based on a coarse timestamping, it’s imperfect, but it can be shown, by simple statistical analysis, that is highly precise for linking blocks. There is a perfect match between the observed behavior of non-Patoshi blocks and the Satoshi client v0.1 source code. Many people hold this historical source code. It’s published in several places in the Internet. If you doubt the authenticity of such source code, you can convince yourself easily that there are some rules governing the ExtraNonce pattern: the probability that the pattern was created by chance is astonishingly low.

Bitcoin Client 0.1 Mining Loop

Bitcoin Client 0.1 Mining Loop

As soon as you look as the ExtraNonce/Time patterns you realize that the Patoshi chain of linked blocks is outstanding: about 22k blocks in total, high slope, dense chain. Both the naked eye and slope-tracking algorithms pinpoints this pattern immediately. The slopes break at some points, where extranonces restart from zero. The slope (the apparent mining rate) of blocks in this pattern is very different from any other chain of blocks and is quite stable except for three fast changes in two years. While there is a small probability that some blocks are incorrectly tagged by the algorithm, most of the blocks can be tagged without dispute. I estimate the tagging error is 0.1%.

The probability that the Patoshi pattern is formed by multiple miners with the same hardware (slope), each starting exactly when the previous one stopped is also astonishingly low (assuming miners can start mining at any random time). Also take into consideration that the pattern slope does not represent its underlying hashrate. Therefore, the Patoshi pattern is “one thing”, not the concatenations of many separate things.

Patoshi Pauses Mining for 10 days, his longest pause.

Patoshi Pauses Mining for 10 days, his longest pause.

There is Only One Patoshi

Some people accepted the existence of the Patoshi pattern, but at the same time refused the argument that a single entity mined the whole P set. Let’s review their arguments:

Main argument against single Patoshi: The pattern is not created by a single miner but by many miners somehow synchronized.

There are four strong reasons to reject this argument:

- 99.9% of all Patoshi blocks are unspent. While only 10% of all non-Patoshi blocks are unspent. This means that the “synchronized” miners decided to spend only 0.1% of their bitcoins, while the remaining miners decided to spent 90% of them (or alternatively each spent 90% of their bitcoins, or each block has a 0.9 probability of being spent). Assuming no correlation between blocks, the probability that only 0.1% of Patoshi blocks being spent is close to 2^-76000. But we can assume high correlation: a miner either sells all his coins or no coin at all. The number of other miners went from 0 to about 25 by March 2010. But the number of synchronized miners in Patoshi pattern would have stayed almost intact, because the hashrate of the Patoshi pattern mostly decreases over time. If we assume the synchronized miners were 6, then the chance they didn’t sell their coins by chance is one in a million.

- Each Patoshi block “links” to a block in the P set, but not to any of the remaining blocks. Somehow the information if a previous block was part or P or not needs to have been communicated along the block. How was this communicated? Early blocks are all look similar. There is no pool signature, as there is today. For what reason would miners do this selective linking? What would they gain? Occam Razor would reject the existence of such system.

- There are some time intervals where the Patoshi pattern interrupts abruptly (i.e. 07-18-2009 for a full day) and then continues from the point it has interrupted. How did all these separate miners coordinate the interruption, while other continued mining without problems? It may be the case that they were running the same version of the client, which failed. But there is no evidence of a special version of the software being distributed.

Second argument against single Patoshi: There was a kind of heterogeneous mining pool formed since Genesis, and many independent users joined the pool.

Strong rejections to this argument:

- Mining pools were invented several years later

- How was the existence of this mining pool secretly communicated before the Genesis block was even created? The Patoshi pattern starts right at Genesis.

- Mining pools were created to reduce reward variance due to the low individual probability of solving a block, but during 2009 single miners could easily solve blocks frequently. Why to pool resources? There is no reason.

- There weren’t enough miners to incentivize pooling, as the Patoshi hashrate corresponds to one to six miners (depending on the assumed efficiency of the involved PCs).

- It would have required specific software (that was never made public) to manage the pool and more software to use it.

- All these being done in secrecy would imply some kind of conspiration, which seems ridiculous.

There is no technical reason, no software developed, no operational expertise at that time, no monetary gain, and no benefit at all for the creation of a mining pool when Bitcoin was launched. Therefore, we can assume there was no mining pool at Genesis time.

Based on the assumption that the pattern comes from a single entity you can directly conclude that this party was using a special mining software and/or hardware: fast as one or more state-of-the-art servers in 2009, and with slightly different rules governing how to mine.

Nonce Restriction in all Patoshi Blocks

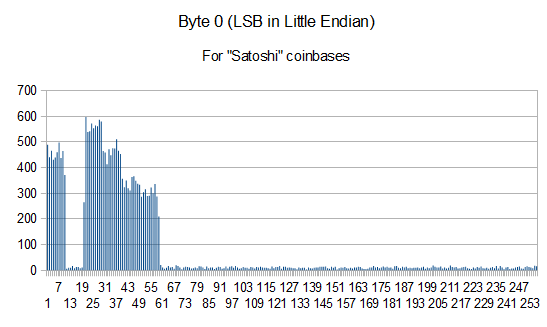

Even if most people were convinced the Patoshi pattern was real, some people still weren’t. But by the end of 2013 things got more interesting: I found proof, beyond any doubt, that the pattern was real, using a completely different method. I discovered that all Patoshi blocks were marked by a reduction of the range of nonces used in published blocks, to a specific range R. We can define R by restricting the least significant byte of the nonce field. This byte normally increments from 0 to 255, but in the Patoshi blocks is reduced to the range [0..9] U [19.. 58].

An Histogram of the LSB Byte of the Nonce Value in the Block Header

An Histogram of the LSB Byte of the Nonce Value in the Block Header

The fact that Patoshi nonces are in this range does not imply the miner of the Patoshi pattern only scanned nonces within this range. It could be the case that the network rejected the solved blocks having nonces out of this range, or the same Patoshi mining software did. This is not the case, as there is a direct relationship between the number of nonces scanned and the average time Patoshi took to solve a block. And the relation suggests the nonce space was reduced to R to create blocks at the rate Patoshi blocks were created. The nonces space scanned is about 1/5th of the full range, and the ExtraNonce increments about 5 times faster.

If you collect the set of blocks whose nonce is in range R, you’ll find it contains 27.68k blocks. I call this set M. The blocks that are in M have the nonce in the R range. The set M is far bigger than one would expect from normal mining. The chances M contains 27.68k blocks assuming uniform nonces is negligible (less than 2^-36000). From the 50k blocks analyzed you would expect that only 10K blocks belong to M, not 28k. But we’ll see this perfectly matches the anomaly of the Patoshi set.

If Q blocks had been marked by restricting the nonce range when scanning, and the remaining elements of M had nonces in R just by chance, then we could compute Q from the following equation (isolating Q): Q + (50-Q)/5 ~= 27.6. The solution is Q=~22k, exactly the size of the Patoshi set. It also indicates there are no other blocks were scanned within the restricted range R except those from Patoshi.

If you re-analyze the common arguments against single-miner for the Patoshi pattern considering this new discovery, the original arguments can’t resist any probabilistic justification. Chances get far lower of what people consider just impossible.

Regarding why the nonce was restricted to the range R, I didn’t know, and I still don’t. These are some of the possible arguments I came up with:

- The restricted range was part of a “trapdoor” to mine blocks with higher probability of obtaining a hash digest below the target.There is a plausible strong reason this to be false: mining faster by restricting the nonce range implies partially breaking SHA256 pre-image resistance. No scientific paper has ever mentioned such a devastating attack, neither for SHA256 nor for standardized hashing functions using the same Merkle–Damgård construction. Any party with the capability to find SHA256 partial pre-images would probably be able to break most commercial communications, from TLS to VPNs, and earn billions. But there is another reason which is mathematical: if you re-mine all Patoshi blocks, trying to find other solutions to the same block templates, will find that the amount of solutions in the R range compared to the amount of solutions out of that range matches the relation of relative range sizes. It was no “better” to mine within that range. The Patoshi set was simply marked to identify something. What? We don’t know.

- The restricted range is user to indicate ownership. If Patoshi were two people, maybe they agreed to give 80% of the block rewards to one of them, and 20% to the other. Then the final owner was marked by specific LSB of the nonce, before scanning the rest of the nonce. This can be proven false, as it would imply Patoshi miners had to increase the extra nonce 256 times more often, which doesn’t happen during the first years. Maybe the restricted range is used to indicate probabilistic ownership: the range R is split into sub-ranges, and it’s fully scanned. The party who gets the bitcoins is the one whose sub-range is randomly picked in the solved block.

- Sub-ranges of R were used to identify different mining hardware cores, where each core would scan a reduced nonce space. This means that Patoshi created the first private homogeneous mining pool. By homogeneous I mean that either all mining machines were setup by a single entity, or a small group of people agreed to use the same type of hardware to fairly distribute earnings. This hypothesis has not been falsified.

At this point I’ve said just a little more from my previous research articles. And from 2014 to early 2019 I didn’t have anything else to say (or to research) about early blocks. Several following studies repeated my research and arrived at similar conclusions. OrganOfConti’s famous blog post contains even more data about Satoshi, describing how he reduced his hashrate in four steps. The last known study, by BitMex Research, comes to the conclusion that Satoshi probably mined 700k coins during 2009-2010. Sadly, they miss the LSB argument entirely (which is the strongest of all known).

But there are people, like nullc, that every now and then go public challenging all this research with old arguments. In a nutshell, I would say that nullc argues a Null Hypothesis: nothing is real. Which is silly because the research was validated by many independent academics.

Null hypothesis: (in a statistical test) the hypothesis that there is no significant difference between specified populations, any observed difference being due to sampling or experimental error.

The reasons why nullc argues this continuously escape my imagination. It’s completely unscientific. The data is there in the blockchain. It doesn’t need rocket science to collect and analyze it. All you need is to grab a Bitcoin blockchain parser. When some weeks ago I read the comments on reddit I felt compelled to refute him again, because … well, because I can. So here I am. Nullc argues that the Patoshi pattern is just the result of some kind of sampling trick. A human interpretation, like shapes in the clouds. He states:

” The million coins being discussed are all unspent coins from the first year, there is fairly strong evidence that they were not mined by a single party (because their nonce incrementing was consistent with multiple parties). If you refer to the lines on the left side of the graph on the page the involved coins there are more like 200k.”. Nullc, 2019. Of course, he doesn’t give any “strong argument” and the “nonce incrementing” is perfectly consistent with multiple parties plus a single party mining most of the blocks. The argument is just silly.

I have three new strong arguments that Satoshi mined close to 1.1M coins (even more than the initial 1M I discovered). I have a more precise figure now because I coded a more accurate pattern-following algorithm. But it’s too much information for a single post, so I’ll just present one argument here. Stay with me just a few more paragraphs. Let’s focus on the first 50k blocks of Bitcoin, from January 2009 to April 2010.

A New Argument Based on Computer Clocks

I’ll prove with overwhelming probability that only a single miner has mined all coins in the Patoshi pattern. If you’ve studied the Bitcoin protocol, you’ll know that block timestamps are not necessarily monotonically increasing. The miner uses its local computer clock to timestamp the blocks. This is true from the Bitcoin source code 0.1.0 to the latest version of Bitcoin Core that had an internal miner (before mining pools were created). There are three things that can affect block timestamps:

- Computer clocks can be unsynchronized from each other. The computer clock is adjusted by most operating systems by slowing down or accelerating the clock increments, but it doesn’t go back spontaneously. A computer that synchronizes with an Internet clock source (a time server) would never lag more than a few seconds.

- Timestamps were not updated continuously during mining. They were only recomputed every 0x40000 nonces in the Satoshi client v0.1 (approximately once every 10 seconds). This means that a timestamp can lag. However, timestamps are always updated when a new best block arrives.

- Block timestamps are adjusted by the Bitcoin software to match the median time of the peers that are connected to a node. The adjustment can be positive or negative. Negative adjustments could imply that future blocks may have prior timestamps. The algorithm used is a bit awkward, as it doesn’t recompute the measurements after a correction. But as time passes, and more nodes have connected in the past, the effect of this adjustment diminishes (the vTimeOffsets vector grows). Therefore, after some time the full node internal time should stay without significative adjustments. Also, the peer to peer network, if highly connected, would converge to a global “median time”.

Because of the reasons expressed in (1) and (3), the same computer will almost never reverse its own timestamps. If a miner creates a block with lower timestamp than its parent, and the time difference between the blocks is D, a small portion of D (such a few seconds) may be caused by (3) but the most part of D is an indirect measurement of the time it took the parent miner to complete the last (unfinished) nonce range scan of 0x40000 elements (~ 10 seconds), corresponding to the lag introduced by (2). In a way, the delta between inverted block timestamps indirectly measures the hashrate of the parent block miner (if all ExtraNonces were incremented at the same rate). Later we’ll say more about these deltas.

If we scan the first 50k blocks to find blocks whose timestamps are lower than their parents’, we should almost never find a case of two consecutive blocks mined by the same miner. If we found many, then that’s an indication we were wrong to think they were from the same miner. And if we found too few compared to the average number of reversals, it would be an indication it’s the same miner indeed.

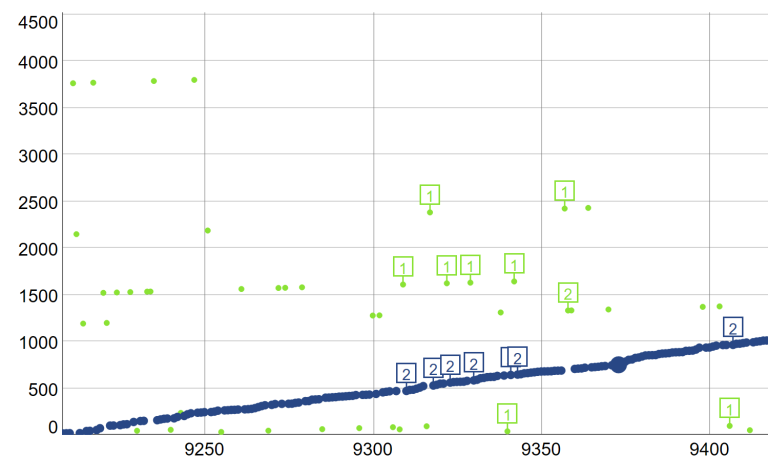

I run a program to find such time inversions and to print when they happened between blocks in the Patoshi pattern, both blocks out of the Patoshi pattern, and between the Patoshi blocks and the remaining blocks. All the data and new nice graphs of every inversion event has been loaded into the new site satoshiblocks.info.

Some cases of Timestamp Inversions (1=Parent / 2=Child)

Some cases of Timestamp Inversions (1=Parent / 2=Child)

To see the complete list of timestamp inversions, go to the satoshiblocks website and click in the “Annotations” checkbox. Each parent is labeled “1”. The corresponding child, which should be the next block, is labelled “2”.

Here is the summary of all classified inversion events:

| Case (parent and child) | Count | Average Time Between Blocks |

| Patoshi and Patoshi | 0 | — |

| Non-Patoshi and Non-Patoshi | 224 | 642 s |

| Patoshi and Non-Patoshi | 398 | 152 s |

| Non-Patoshi and Patoshi | 72 | 1079 s |

| Total | 694 |

There are no time inversions between Patoshi blocks. Zero. This result is very relevant considering the Patoshi blocks account for 43% of all the blocks in the first 50k. I’m open to consider other explanations, but for me this can only mean one thing. There is a single PC clock whose time is stamped in the Patoshi blocks. A single software that controls how block templates are created. A single miner.

So who is Patoshi? The single miner that mined ~ 1.1M bitcoins?

There is evidence that links the Patoshi patterns to Satoshi, based on public information sources and the blockchain, of course. But I would prefer to stop here. Leave Patoshi alone once for all. I have too many things to build for Bitcoin, like RSK.

But I expect more denial posts in Bitcoin forums. And if that happens, then it’s my call.

You can find more information about Satoshi blocks in the following articles:

- The Well Deserved Fortune of Satoshi Nakamoto, Bitcoin creator, Visionary and Genius (SDL, 2013)

- Satoshi’s Fortune: a more accurate figure ( SDL, 2013)

- A new mystery about Satoshi hidden in the Bitcoin block-chain ( SDL, 2013)

- Satoshi’s Machine: One Mystery is solved and another one opens ( SDL, 2013)

- Reawaken interest in Chain-Archeology ( SDL, 2014)

- July 2009 Mystery Solved ( SDL, 2014)

- How you will not uncover Satoshi ( SDL, 2014)

- Satoshi’s hashrate (OrganOfCorti, 2014)

- A little more on Satoshi’s blocks (OrganOfCorti, 2014)

- Another short post on mapping the historical hashrate distribution (OrganOfCorti, 2014)

- Does Satoshi have a million bitcoin? (BitMEX Reseach, 2018)