This is a curated collection of posts and essays from Nic Carter created on June 4, 2020.

This is a curated collection of posts and essays from Nic Carter created on June 4, 2020.

WORDS is a monthly journal of Bitcoin commentary. For the uninitiated, getting up to speed on Bitcoin can seem daunting. Content is scattered across the internet, in some cases behind paywalls, and content has been lost forever. That’s why we made this journal, to preserve and further the understanding of Bitcoin.

Visions of Bitcoin

How major Bitcoin narratives changed over time

By Nic Carter & Hasu

Posted July 29, 2018

Do I contradict myself? Very well then, I contradict myself I am large, I contain multitudes.

– Walt Whitman, Song of Myself

Perhaps the most enduring source of conflict within the Bitcoin community derives from incompatible visions of what Bitcoin is and should become. Businesses building on Bitcoin, believing it a cheap global payments network, eventually became nonviable when blocks filled up in 2017. They weren’t necessarily wrong, they just had a vision of the world that ended up being a minority view within the Bitcoin community, and was ultimately not expressed by the protocol on their desired timeline.

In the absence of a recognized sole leader, Bitcoiners refer to founding documents and early forum posts to attempt to decipher what Satoshi truly wanted for the currency. This is not unlike US Supreme Court justices poring over the Constitution and applying its ancient wisdom to contemporary cases. Others reject textual exegesis and focus instead on a pragmatic analysis in context.

Conflicts within Bitcoin thus arise from entities who hold visions of the protocol that are mutually exclusive — and this leads to friction when these visions cannot be reconciled. Visions of Bitcoin are not static. Technological developments, practical realities and real-world events have shaped collective views. This post is an attempt to aggregate the various dominant narratives that have characterized Bitcoin throughout its 9-year history. This post builds on excellent prior work by Murad Mahmudov and Adam Taché, and we suggest you add that to your reading list.

Changing narratives

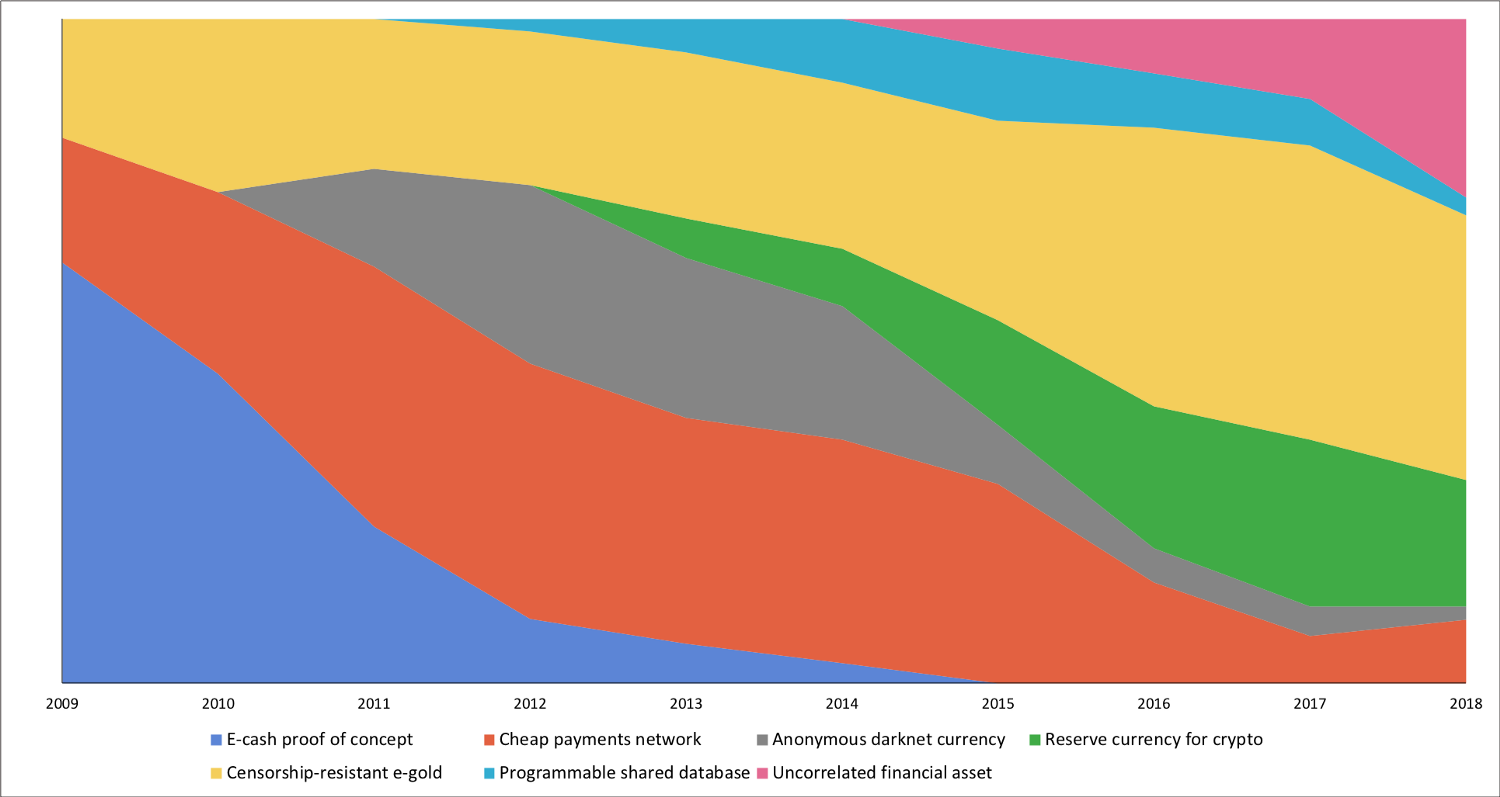

Here, we want to more granularly explore the prevalence of key narratives. We identify seven distinct major themes that have held positions of prominence among Bitcoiners throughout its history. Note that these do not necessarily have to be the most influential narratives — we are instead focusing on major strains of thought that have characterized Bitcoin users.

In rough order of appearance, these are:

- E-cash proof of concept: the first major narrative, this was the general view of Bitcoin in its earliest days. Back then, cypherpunks and cryptographers were still appraising the nascent project and determining whether it worked, if at all. Since all prior e-cash schemes had failed, it took a while for people to be convinced of its technical and economic viability and move on to more expansive conceptions of the protocol.

- Cheap p2p payments network: an extremely popular and pervasive narrative. Some believe this is what Satoshi had in mind — a straightforward currency for peer to peer internet transactions. A decentralized Paypal or Venmo, if you will. Since microtransactions are a key component of internet commerce, proponents of this view generally believe that low fees and convenience are an essential characteristic of such a currency.

- Censorship-resistant digital gold: the counterpoint to the p2p payments narrative, this is the view that Bitcoin primarily represents an untamperable, uninflatable, largely unseizable, intergenerational wealth store which cannot be interfered with by banks or the State. Proponents of this view de-emphasize Bitcoin’s use for everyday transactions, arguing that security, predictability, and conservatism in development are more important. We’re callously lumping in sound money believers into this camp.

- Private and anonymous darknet currency: the view that Bitcoin is useful for anonymous online transactions, in particular to facilitate black market online commerce. This is not necessarily mutually exclusive with the e-gold position, as many proponents of the digital gold view believe that fungibility and privacy are important attributes. This was a popular narrative before the chain analysis companies had success de-anonymizing Bitcoin users.

- Reserve currency for the cryptocurrency industry: this is the view that Bitcoin serves an essential purpose as the native currency for the cryptocurrency/cryptoasset industry more generally. This is a view espoused by traders for whom BTC is the numeraire — the currency in which the prices of other assets are quoted. Additionally, traders, businesses, and distributed networks that hold reserves in BTC de-facto endorse this view.

- Programmable shared database: this is a slightly more niche view, and generally involves the understanding that Bitcoin can embed arbitrary data, not just currency transactions. Individuals holding this view tend to see Bitcoin as a programmable, expressive protocol, which can facilitate broader use-cases. In 2015–16, it was popular to express the notion that Bitcoin would eventually absorb a diverse set of functionalities through sidechains. Projects like Namecoin, Blockstack, DeOS, Rootstock, and some of the timestamping services rely on this view of the protocol.

- Uncorrelated financial asset: this is a view of Bitcoin that treats it strictly like a financial asset and finds its most important feature to be its return distribution. In particular, its tendency to have a low or nonexistent correlation to all manner of indexes, currencies, or commodities makes it an attractive portfolio diversifier. Proponents of the view are generally not too concerned about owning spot Bitcoin; they are interested in exposure to the asset. Put another way, they want to buy Bitcoin-flavored risk, not necessarily Bitcoin itself. As Bitcoin has become more financialized, this conception has gained steam.

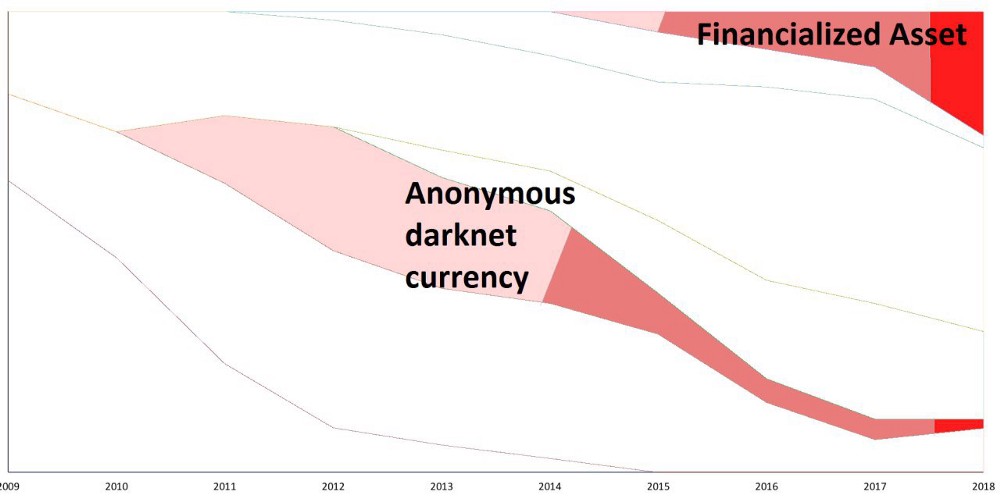

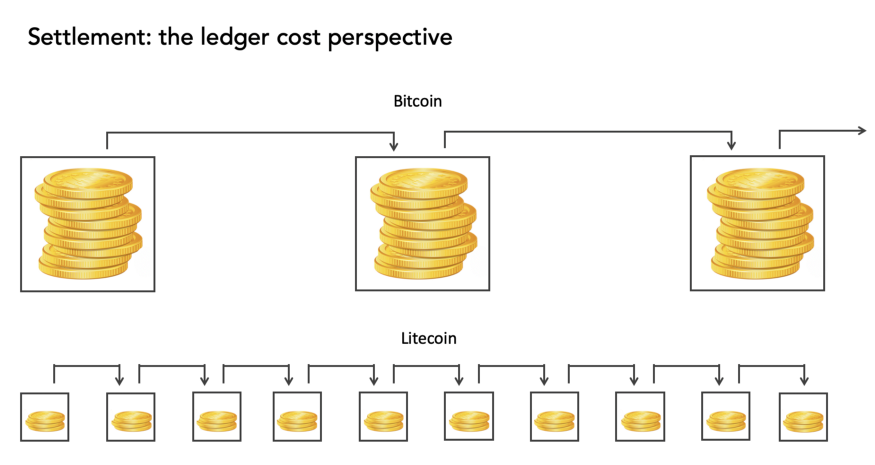

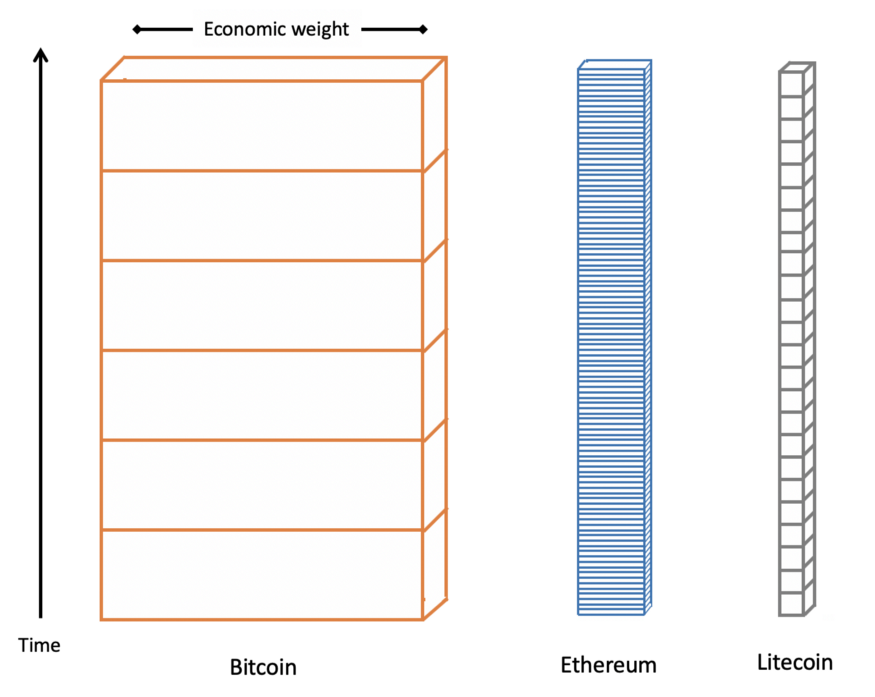

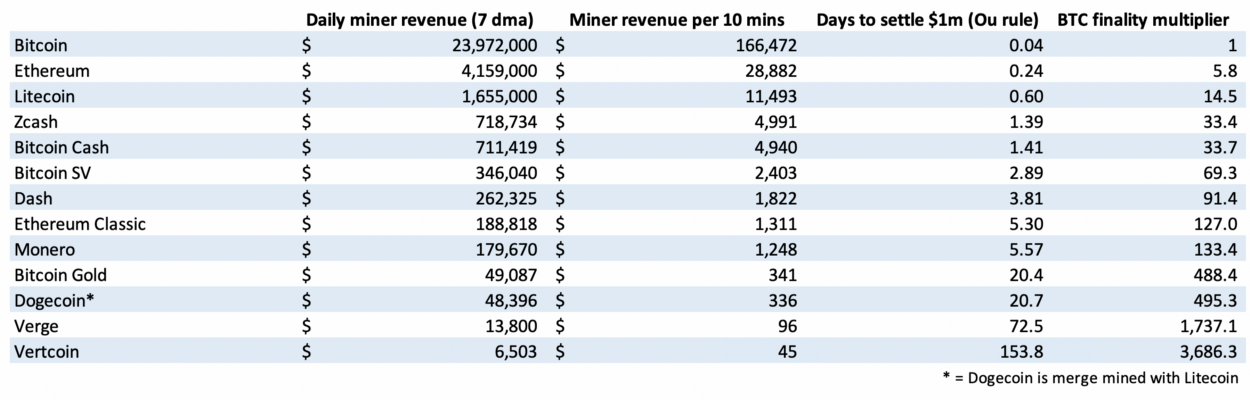

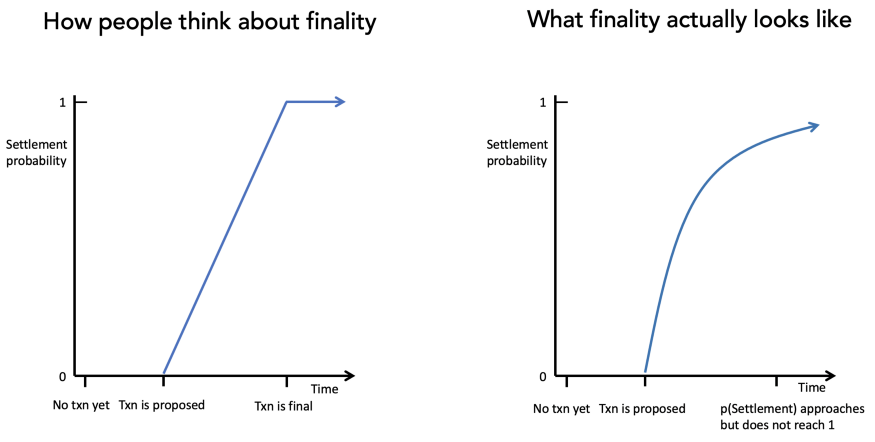

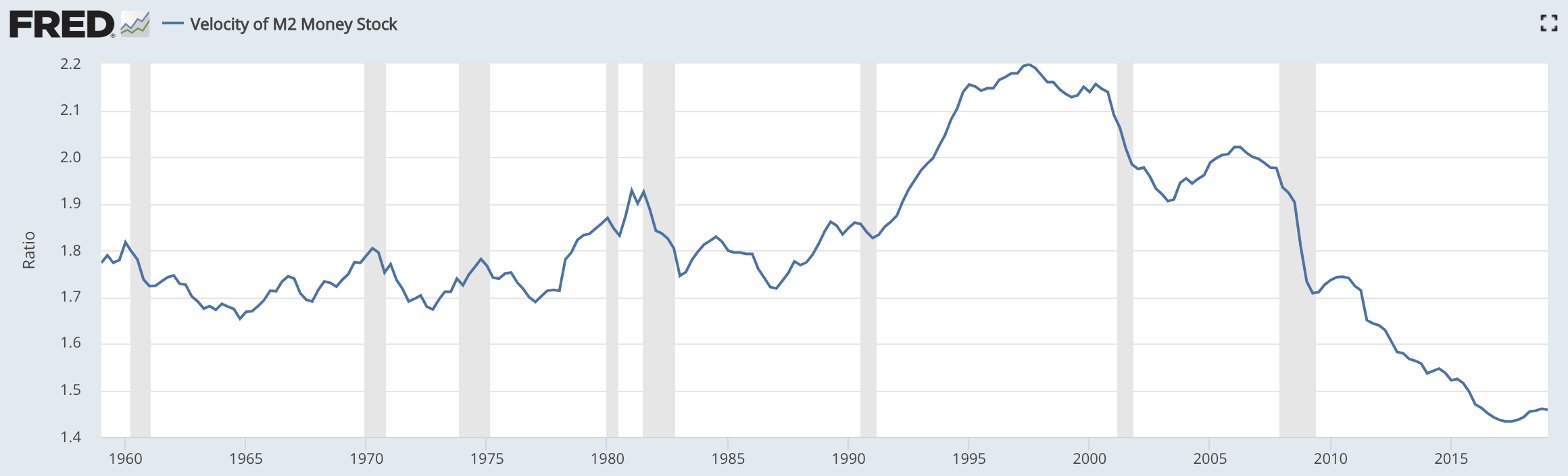

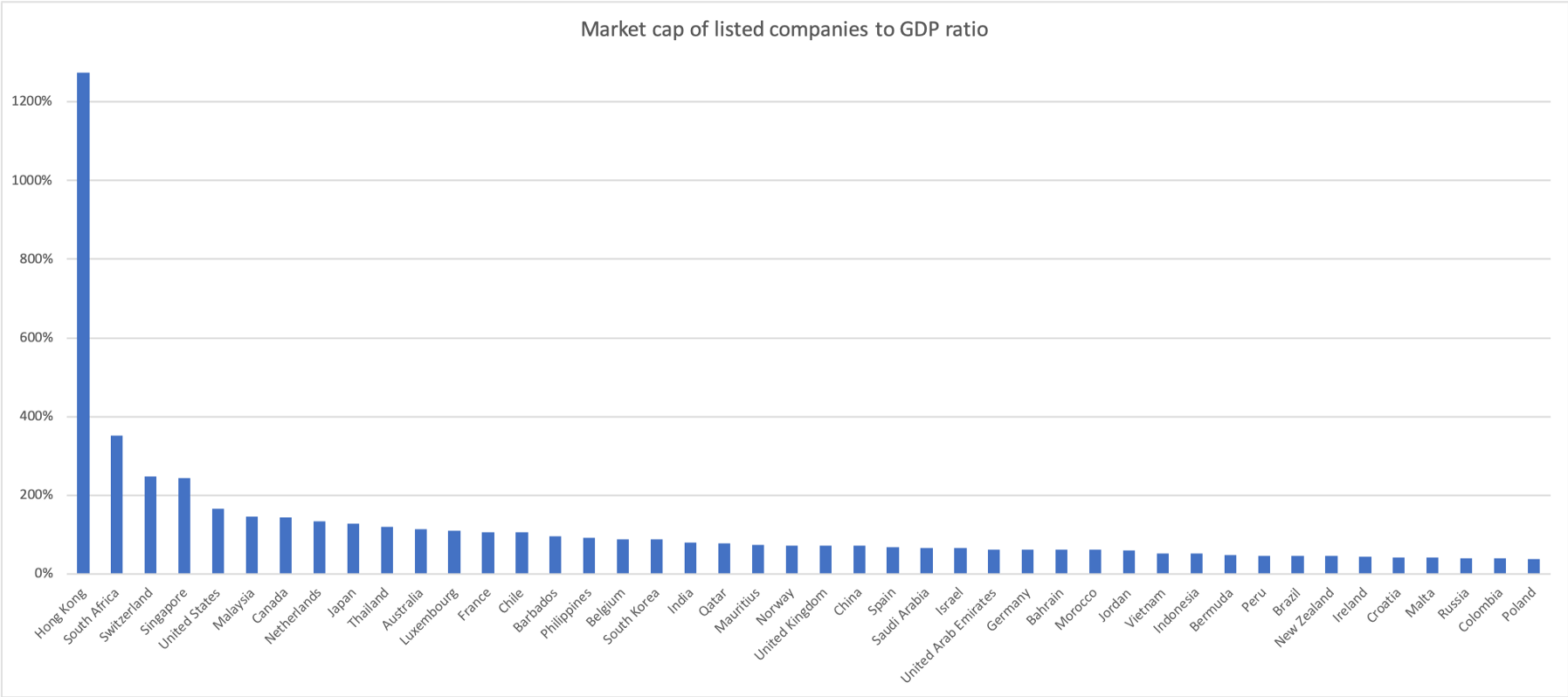

In the chart below, we’ve weighted these various narratives according to their popularity at the time.

This isn’t modern art — it’s our representation of Bitcoin’s changing tides

This isn’t modern art — it’s our representation of Bitcoin’s changing tides

In this chart, we lay out the relative influence of the seven narratives we identified above. As you can see, the e-cash proof of concept was the dominant view at the start, although the p2p payments network and digital gold views were also espoused at the time. Later, Bitcoin as an anonymous darknet currency gained steam with the Silk Road. The idea never really died off, and Bitcoin is still used on the darknet today, even though other privacy-oriented alternatives exist.

As ICOs were invented and a broader market of altcoins began to proliferate, BTC became the reserve asset for that larger economy. This grew to become a significant feature of Bitcoin, especially in the bull markets of 2014 and 2017. We note that the p2p payments contingent remained influential until mid 2017, when they largely migrated to Bitcoin Cash (some had already left for Litecoin and Dash). However, with the emergence of Lightning in 2018, there has been an upswing of enthusiasm for online microtransactions and fee-less internet payments.

In 2015 and 2016, sidechains became a popular talking point, and it was assumed that Bitcoin would soon boast a much-expanded functionality, obsoleting most altcoins. Related functionality-extending projects like Mastercoin (now Omni), colored coins, Namecoin, Rootstock, Blockstack, and Open Timestamps, contributed to this general view. However, as sidechains proved complicated to implement, non-money uses of Bitcoin fell out of favor.

As Bitcoin emerged from the 2014–15 bear market, analysts began to contemplate its status as a differentiated commodity-money. In November 2015, Tuur Demeester published an investment note entitled “How to Position for the Rally in Bitcoin,” arguing that it had unique characteristics as a portfolio asset. In mid-2016, Burniske and White influentially argued that Bitcoin represented an entirely new asset class. These analysts noticed Bitcoin’s stubbornly low correlations with traditional assets, and as this persisted, Bitcoin as a portfolio diversifier gained steam among certain forward-looking corners of the asset management industry. Today this is a popular view, driving much of the demand for financial products which would give traditional investors exposure to Bitcoin.

Throughout all these regimes, the digital gold conception has remained influential, and now is the consensus view, predominating over the p2p petty cash faction, which largely departed with Bitcoin Cash. Today, after years of strife and infighting, this is the majority view. However, not all Bitcoin users are ideological bitcoiners, and wanted to reflect this in the chart. Many Bitcoin holders hold it as a portfolio diversifier, some still use it for anonymous darknet transactions, and the p2p cash contingent has re-emerged alongside Lightning.

Tension and release

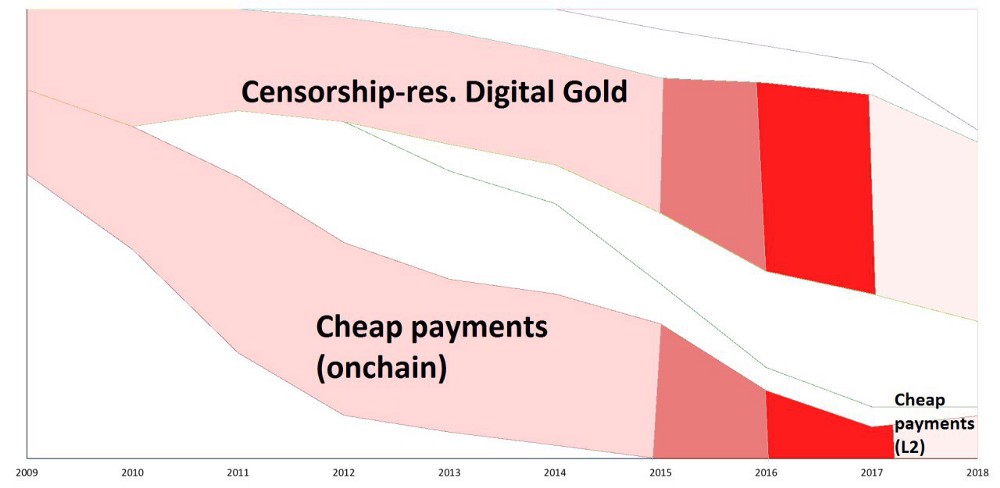

If you scrutinize the above chart, you’ll notice that some of the visions of Bitcoin are entirely incompatible. For instance, a move to a global on-chain payments network conflicts with the digital gold view, as emphasized by Spencer Bogart. We’ve depicted the conflict between these views of the world by isolating them on this chart.

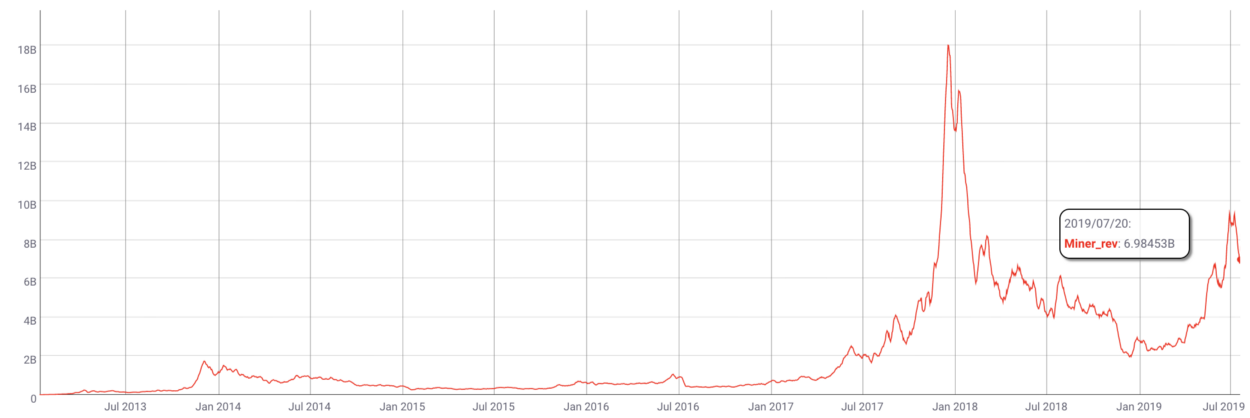

The conflict really began to be fought seriously with the release of BitcoinXT in 2015, although rancorous discussions had long preceded that. Further provocations including Bitcoin Classic, Unlimited intensified the conflict. It reached its peak in mid 2017 when Bitcoin Cash finally forked. During the bull run of late 2017, Bitcoin fees reached extreme levels, leading to defections to the Bitcoin Cash camp. However, since then, fees have settled down and the need for big blocks appears less urgent.

Additionally, in early 2018, Lightning implementations became viable, and micropayments with Bitcoin emerged. Thus, the tension dissipated, as both camps were able to pursue their own objectives. We noted an uptick in the cheap payments school of thought from within the Bitcoin crowd in 2018, as there has been a resurgence of optimism for payments through second-layer solutions.

An interesting conclusion that we think can be drawn from the analysis is that Bitcoin is currently benefiting from a rare period of relative harmony. While there is no single view that entirely dominates, the digital gold narrative is certainly most prevalent right now. The civil wars of 2015–17 ended with the Bitcoin Cash fork, and migrations to other p2p payment factions like Litecoin, Dash, and Nano. For now, the tension seems to be largely resolved, and we find ourselves in an unusually placid era in Bitcoin’s history. Subjectively, it appears that under this comparatively peaceful regime, development seems to be progressing more rapidly. Endless social media battles, conference-driven agreements, and positioning for contention forks certainly created a drag on developer efforts. There is another battle looming, however.

As depicted in this chart, the anonymous and fungible vision of Bitcoin (generally preferred by the digital gold camp) is somewhat at odds with the financialised, transparent version which is growing in popularity. Individuals that want exposure to Bitcoin the financial asset tend to prefer a Bitcoin which is compatible with AML/KYC and tend to put a lesser emphasis on privacy or fungibility. Many pundits believe this will be the next bitter fight for the soul of Bitcoin.

Ultimately, both the conflict and the peacetime phases are important. Conflicts reveal where power structures reside, and tend to yield informative signals about how key stakeholders truly feel. Under duress, business, individuals, and developers are forced to take sides, revealing their genuine preferences for the development of the protocol.

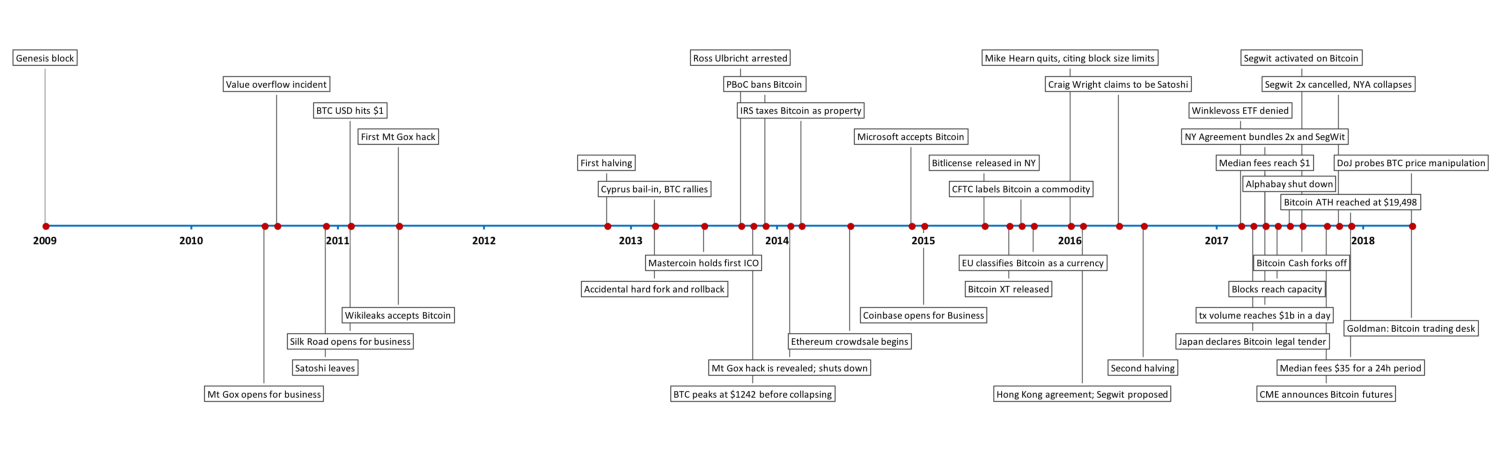

Timeline of events

We are aware that much of our analysis relies on our subjective interpretation of old BitcoinTalk posts. If you disagree, we welcome you to suggest an alternative. To make subsequent analyses easier, we’ve put together a timeline of key Bitcoin events, tracking its entire history. (We drew heavily on the 99bitcoins annotated price chart to make this.) We recommend considering our colorful ‘changing tides’ chart alongside the below timeline. The juxtaposition should help elucidate why exactly we made the decisions that we did.

Conclusion

We put together the changing narratives chart through an analysis of BitcoinTalk posts, a set of discussions with Bitcoiners who had been there from the very start, a healthy respect for Bitcoin history, and a recollection of major attitudes over the years. Anyone who has been around Bitcoin long enough should be able to perform a similar analysis.

We’re not positing our analysis as the absolute truth. Instead, we want to nudge Bitcoiners away from absolutism and acknowledge that major narratives within the Bitcoin community have changed over time. And that’s ok — it’s appropriate to change your mind in response to new data. Purity tests are generally weak, since they tend to require that individuals do not evolve. But if most Bitcoiners went back and contemplated their own past histories, they would probably find that they evolved over time, too. Both of the authors have certainly been through the cycle.

In the end, a healthy respect for Bitcoin history is a necessary starting point of any attempt to define it. It is not unitary, and Bitcoiners are not ideologically homogenous. Bitcoin contains multitudes, and it’s important to remind ourselves of that.

Thanks to Dan McArdle and Murad Mahmudov for the input.

Media Coverage of Bitcoin Is Still a Total Disaster

A recent Washington Post article shows how journalists get cryptocurrency wrong

Nic Carter

August 11, 2018

I ‘m fed up with journalists who are either ignorant or unwilling to learn about cryptocurrency holding forth on its perceived weaknesses. Recently, the Washington Post published a piece entitled “Bitcoin is still a disaster” by economic affairs reporter Matt O’Brien, which I feel relies on mistaken assumptions to paint a misleading picture of the world. Today, I’d like to engage with some of the claims made in the piece, and show how O’Brien — among many others — get it wrong.

Claim: Currencies are meant to be stable

“There’s one thing a currency is supposed to do that bitcoin never has. That’s maintain a stable value.”

This assumes that bitcoin is a currency, and that the definition of currency is normative (“x should do y”) as opposed to descriptive (“things of type x have the qualities y and z”). I’d classify Bitcoin the protocol as a complete monetary system, and bitcoin the unit of value as a commodity money, which has the potential to become a gold-like reserve currency. Commodities fluctuate — that’s what they do.

Additionally, currency isn’t meant to maintain a stable value. Monetary policy is used for a variety of macroeconomic objectives, including targeting GDP growth, unemployment rates, inflation, trade balances, and more. If stability was the objective, the Federal Reserve Board would target zero percent inflation rather than the two percent that it currently does. Am I moving the goalposts? It’s matter of figuring out how bitcoin is used, and what it was intended for. I’m not sure [bitcoin creator] Satoshi Nakamoto ever defined bitcoin as a currency. He defines it as a system for electronic transactions, a peer-to-peer version of electronic cash, and an electronic payment system. He envisions bitcoin as a protocol and a bearer digital unit of value.

The interpretation of bitcoin as a currency is mostly inferred by outsiders imposing a particular view upon the protocol. Unburdened by priors, a neutral analyst would probably describe it as something similar to gold. In fact, Satoshi described PoW (proof-of-work) with a reference to gold mining, and later discussed bitcoin as analogous to a scarce, inert, infinitely portable metal which might develop a monetary premium. He clearly saw it as a gold-like commodity which would recapture those same properties in the digital realm, and I think this the most fitting interpretation of the system.

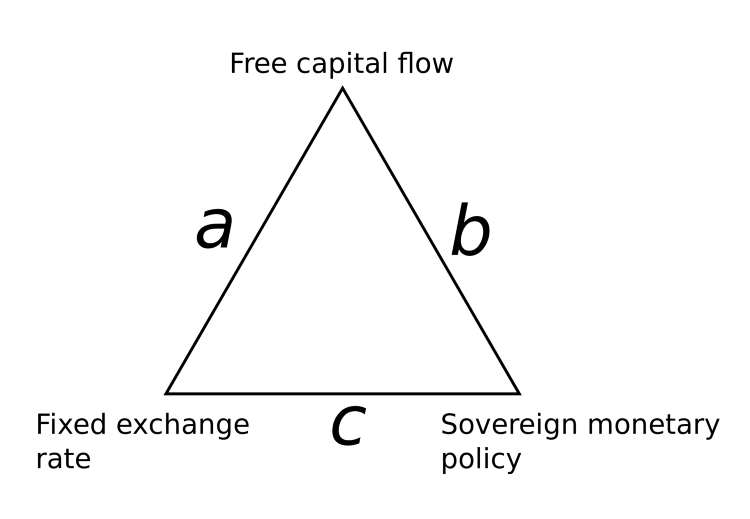

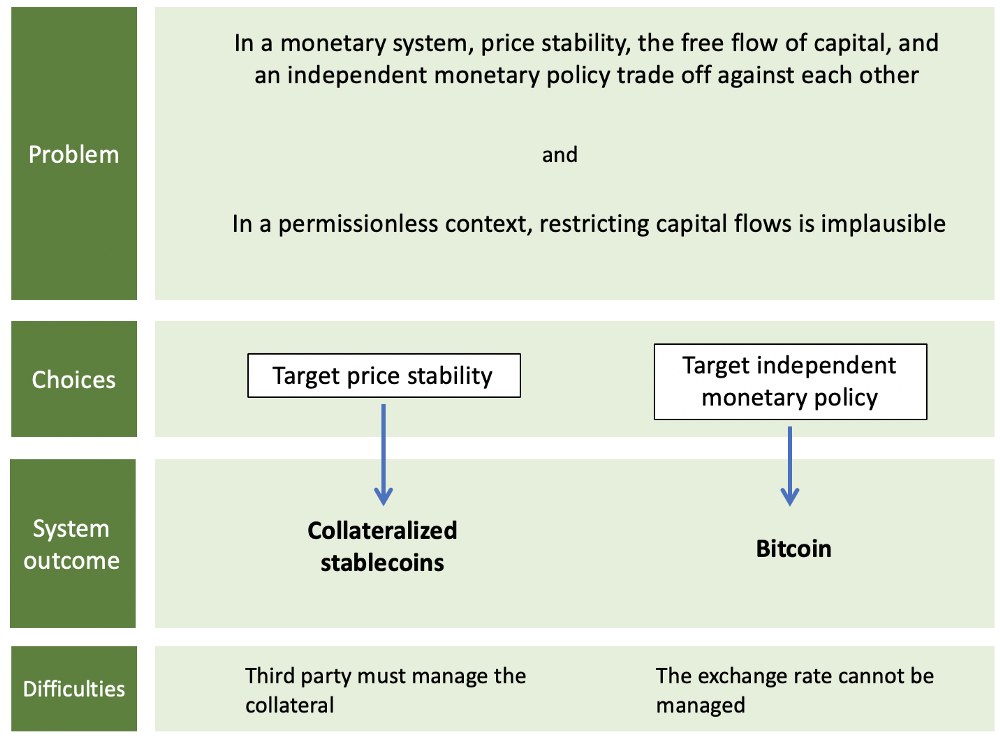

Claim: Bitcoin was designed with volatility in mind

“Why has bitcoin’s price been so up-and-down? Well, part of it is that it was designed that way.”

This is an odd rewrite of history, or more charitably, a very strange interpretation of bitcoin’s purpose. The impossible trinity tells that it’s impossible to have free capital flow, sovereign monetary policy, and a fixed exchange rate all at the same time. Bitcoin was designed with sovereign monetary policy and a free flow of capital. No one underwrites or backs bitcoin, so it cannot be pegged to a real-world basket of goods. That’s the same with gold. Both have emergent monetary premia. This can’t be planned for — it just so happened that way. Needless to say, Satoshi didn’t design bitcoin to be unstable, he wanted to solve the problem of double spends with digital cash such that it didn’t rely on a single validator. Its volatility is an emergent property, not a design objective.

Claim: Validating transactions is the source of its computational overhead

“[…] the problem [with a decentralized network] was that the only way to do that would be for every member of that network to keep a record of every bitcoin transaction there had ever been — that way they knew who had bitcoin to spend — which would require_a lot _of computing power.”

This is a common misconception. PoW and mining ensures that the network deterministically converges to a shared history, without any subjectivity or off-chain coordination. The fact that the minted units have value means that miners are incentivized to behave appropriately in the short and medium term. And the fact that those units are worth $x means that miners will pay anything up to $x to obtain them. This is the source of the large quantities of computing power allocated to the network — the combination of efficient mining hardware and large amounts of value at stake.

The validation and record-keeping is behavior conducted by full nodes, not miners. The cost of maintaining the bitcoin data store is an externality pushed onto full nodes through bandwidth and storage costs. This is NOT the job of miners. This is a basic distinction lost on many.

Claim: Bitcoin’s volatility is unnatural

“But even this inbuilt volatility doesn’t fully explain why bitcoin has been on such a roller-coaster ride. Something else must be going on, and that something is plain-old manipulation.”

Volatility isn’t inbuilt, it’s a feature of every non-pegged economic asset. The Post should keep its fragilista-thinking to itself.

Does the Post have any proof that markets are not long-term efficient? If so, they have a Nobel prize in economics to collect.

Plain old manipulation? You really mean to tell me you think a $100 billion network was manipulated into existence? Is it so difficult to accept that bitcoin provides a differentiated, useful service to millions of people worldwide, and that’s why it has value? Does the Post have any proof that markets are not long-term efficient? If so, they have a Nobel prize in economics to collect.

“[…] what seems to still be happening in 2018 with various pump-and-dump schemes.”

Don’t conflate bitcoin with random worthless altcoins. There is a lot of PND [pump-and-dump] in this industry, but it is infeasible in the extreme to PND bitcoin. If you’re part of a PND group, you target alts in the $50–$300 million range, not bitcoin.

Claim: Bitcoin is only used as a currency due to the wealth effect

“The first is that what makes bitcoin work as a way to transfer things — the expectation that its price will keep rising.”

That’s not what makes it work. It works as a way to transfer things because it’s a pretty good distributed clearinghouse for value. If bitcoin were stagnant at $1000 for the next ten years, it would remain a good way to transfer things.

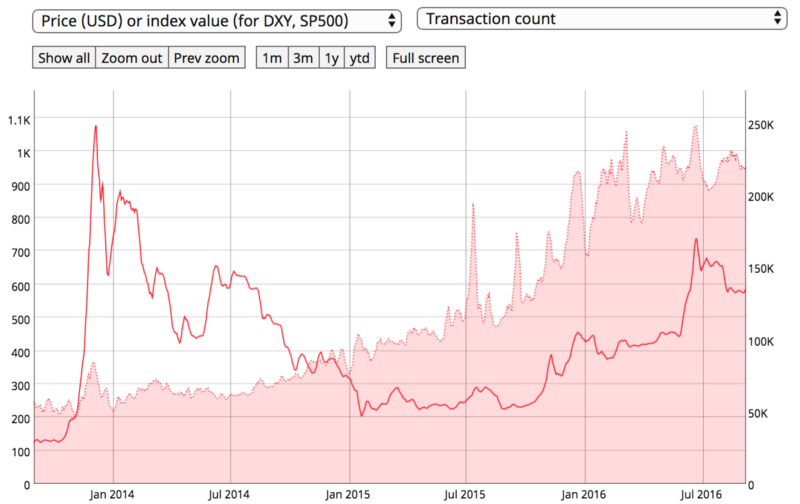

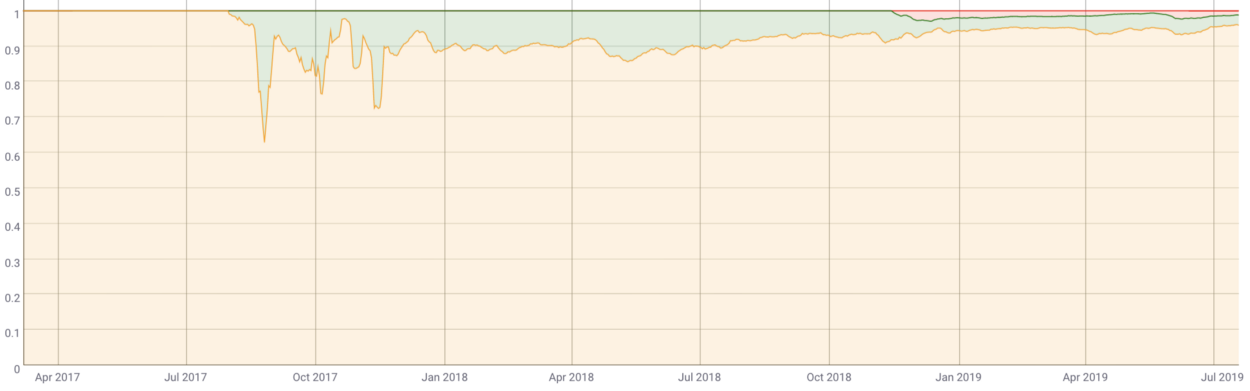

During the 18-month bear market that began in January 2014, people still used bitcoin. In fact, usage grew consistently the entire time.

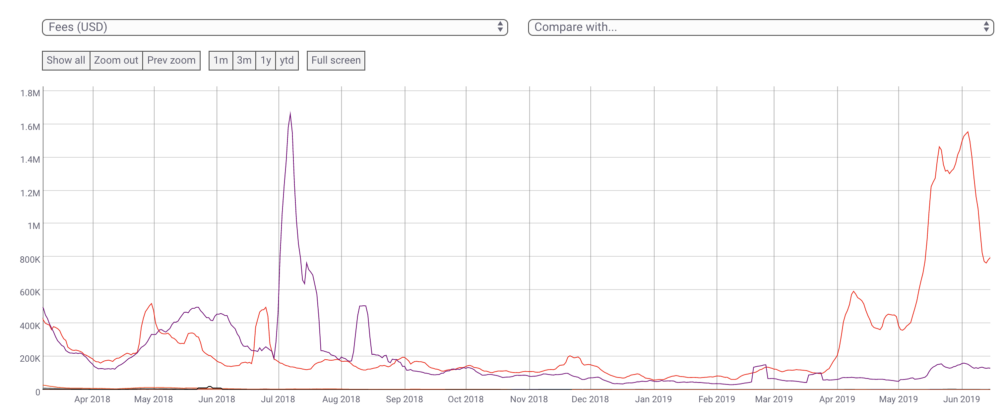

Price (solid red line) and transaction count (shaded red area) during the 2014–16 bear market. Image: Coin Metrics

Price (solid red line) and transaction count (shaded red area) during the 2014–16 bear market. Image: Coin Metrics

Bitcoin offers transactors a rival benefit; something they cannot find anywhere else. It’s unique among cryptocurrencies, as it boasts the best reliability, uptime, dedicated track record, and protocol developer community. It’s unique among monetary assets because it offers properties not instantiated by gold or the USD. There’s a reason people choose bitcoin.

Claim: Bitcoin’s deflationary characteristics mean that no one uses it

“Why spend $100 worth of bitcoin today if you think it’s going to be worth $1,000 in a not-too-distant tomorrow? You wouldn’t. And people aren’t.”

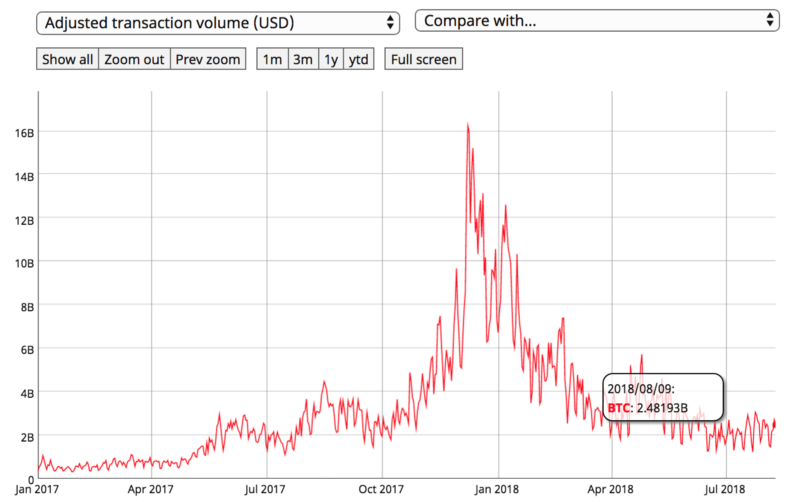

Shameless plug: I urge you to consult my website Coin Metrics, where we make this data free and available so anyone can use it. Conservatively, bitcoin saw $2.5 billion in on-chain transaction volume yesterday. That’s omitting all the off-chain transactions that occur on Opendimes, on second-layer networks like Lightning, and internally at Xapo and at Coinbase.

Image: Coin Metrics

Image: Coin Metrics

In the last year, bitcoin routinely hosted the transfer of $2B worth of bitcoin a day, up to a peak of about $16B of bitcoin a day. That’s a lot of fake transactions. The anticipated response to this from the skeptic is that on-chain volumes are just a clearinghouse for the multitude of exchanges worldwide, or simply a way for individuals to access the altcoin casino. The former is probably true; we have good evidence that bitcoin is mostly an industrial network dominated by exchanges and power users rather than one that caters to end-users. Using the rough heuristic that industrial users tend to batch transactions, we can see that 30–40 percent of the network is industrialized in this manner.

There’s nothing wrong with this. It simply means that bitcoin acts as a decentralized global settlement network for a number of endpoints that connect it to everyday economic systems, with which users transact at the individual level. This is pretty radical! A decentralized, neutral, untamperable central bank that settles flows on a continuous basis between a global network of smaller banks (exchanges, merchants, and custodians). What a concept.

As for the “bitcoin as an on-ramp to the altcoin casino view,” if this were true, then bitcoin would have cratered along with altcoins as they fell 80–90 percent over the last six months. However, bitcoin has shown great strength against altcoins during the bear market. If you look at any index, bitcoin has regained dominance. This pokes holes in the story that it is only used for access to altcoin pump and dumps.

For context, here’s the Bletchley total market index quoted in bitcoins since December. Ever since the contraction began in January, bitcoin has strengthened against the rest of the cryptoasset market.

Image: Bletchley Indexes

Image: Bletchley Indexes

You wouldn’t expect this if bitcoin was only a vehicle for speculation on other cryptocurrencies. Clearly, there is demand for bitcoin in its own right.

Claim: Bitcoin is illiquid and hence manipulated

“This lack of liquidity makes it pretty easy for a few fraudsters to push the price up quite a bit.”

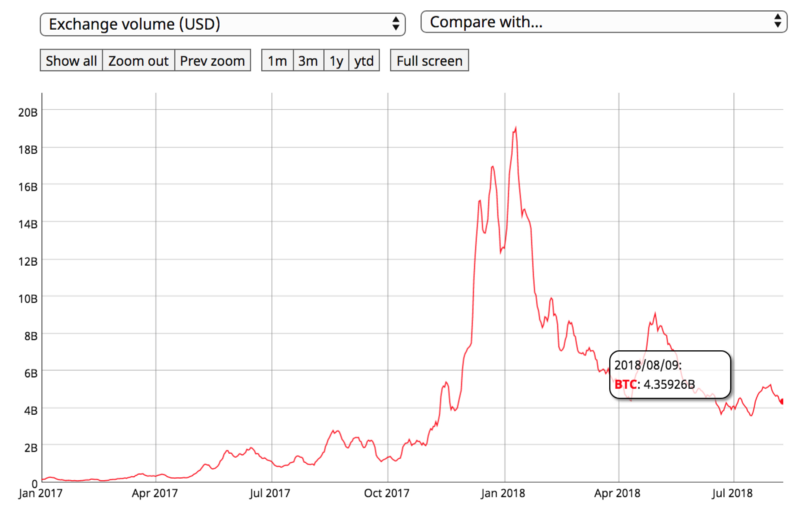

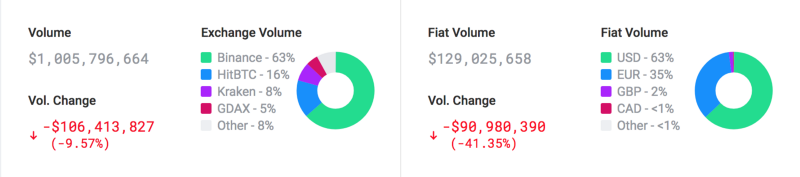

This isn’t the case, and relies on a flawed reading of the Tether situation. Fundamentally, bitcoin is quite liquid. It has huge volumes on listed exchanges, and probably the same amount again on over-the-counter providers like Cumberland, Circle, Genesis, and Octagon.

Much illiquid. Very manipulation. Image: Coin Metrics

Much illiquid. Very manipulation. Image: Coin Metrics

Even if you subtract all Tether volume, and all volume from synthetic exchanges like BitMEX, and all swaps and futures volume from the CME and CBOE, you have robust volumes. The market for BTC → fiat (on the right in the chart below) is also quite liquid.

Image: Nomics

Image: Nomics

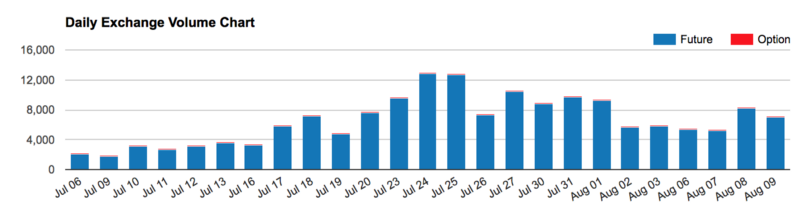

If you look at the market for fully-regulated futures exchanges, the picture is sunny.

CME daily volumes (contracts are for 5 BTC). Image: CME Group

CME daily volumes (contracts are for 5 BTC). Image: CME Group

Yesterday, 7077 contracts were traded at the CME — equivalent to $215 million. The liquidity picture is strong, and improving.

Claim: Bearer assets are dangerous and illegal

“There’s a reason, after all, why bitcoin has attracted so many scammers: All its transactions are irreversible.”

You have to take the bad with the good. It’s a digital bearer asset, which is completely new. Of course people want to scam with it — it’s the best money ever invented. That USD is never used by scammers, right?

“All of which is to say that if you steal a bitcoin, you get to keep a bitcoin.”

If you earn a bitcoin, you get to keep a bitcoin. If you mine a bitcoin, you get to keep a bitcoin. Strong property rights are a hell of a thing. This is just an incentive to build more secure wallet and custody software. We’re halfway there already.

Claim: Bitcoin still relies on a trusted set of intermediaries

“Bitcoiners think all of this is worth it. That it’s better to have a financial system that is clunkier, costlier and more vulnerable to attacks than it is to have to trust someone — or, more accurately, to_admit _that you have to trust someone.”

Using bitcoin doesn’t rely on trust in an individual. If you run a node, use a hardware wallet or a well-concealed paper wallet, and maintain good opsec, you are pretty much set. Of course, to obtain your bitcoin, you may have to use Gemini/GDAX/Square. But no one is forcing you to hold your bitcoin on an exchange. It’s only long-term storage on an exchange which requires significant trust in the institution. And bitcoiners universally, vociferously, encourage people not to do that.

Nothing backs bitcoin or pegs it to a basket of assets. That’s the point. Bitcoin was designed specifically to avoid the influence of a single authority.

More broadly, bitcoin doesn’t remove trust entirely. That’s a straw man frequently knocked down by critics. Bitcoin reduces the need for trust in a single institution. Instead, you just have to trust that the code is well-vetted in the typical FOSS [free and open-source software] manner, that the economics that underscore mining continue to hold, and that discrete log problem is still hard. We have plenty of evidence that these things all hold, and will continue to hold. And we have plenty of evidence that, conversely, a single institution in control of the money supply will always abuse its power. If you don’t believe me, just check out what’s happening in Turkey today. Seignorage is a drug — and it’s pretty much impossible to kick the habit.

“Bitcoin exchanges require some measure of [trust] whether they realize it or not.”

Centralized exchanges do. There exist non-custodial peer-to-peer exchanges, like Hodl Hodl and Bisq, for bitcoin. LocalBitcoins is another peer-to-peer exchange that places reduced reliance on a single intermediary. Even centralized exchanges can conduct periodic proofs of solvency, if users demand it. And, as with the rest of finance, if the brokerages/exchanges/clearinghouses are regulated under functional regimes, they are strongly incentivized not to run fractional reserves or lose user funds.

The broader point here is that relying on centralized exchanges is inevitable. Many people will trade off decentralization for convenience, and we can’t stop that. We can demand that exchanges behave appropriately. There are many exchanges and custodians with long histories of robustness, resilience, and integrity. There is a market for exchanges, and the badly-run ones will fail.

To sum up

The problem with this article is that the pundit in question has settled on a narrative — bitcoin is a poor economic system — and then searched for various datapoints that confirm his view. Bitcoin is volatile, yes. It is an emerging commodity-money that’s becoming financialized and growing from a small tribe of enthusiasts to a global user base. Of course it’s volatile. Growth is not linear. Only fragilistas demand it to be so.

Nothing backs bitcoin or pegs it to a basket of assets. That’s the point. Bitcoin was designed specifically to avoid the influence of a single authority. Bitcoin is priced exactly where it ought to be — this is always true. Manipulation might work on a 15-minute time frame, but it’s just implausible in the extreme that a $100 billion-plus asset class has been manipulated into existence.

Yes, bitcoin relies on exchanges to provide exit ramps for individuals that want to reduce their reliance on sovereign currencies. Sometimes those exchanges get hacked and fail. That is entirely natural. Bitcoin continues to chug along unaffected. It’s extremely popular; its strong assurances and settlement guarantees grant it daily volumes in the billions. It is a single order of magnitude behind Visa’s economic throughput — that’s right, just one 10x away. The gap will probably be closed in the next year. It has an unmatched record of reliability, resilience, and resistance to cooption. For a nine-year-old, this is a pretty good track record. If it were a human, it would be midway through the fourth grade.

Pundits will continue to ignore this; not because they’re incapable of reading the data, but because they don’t want to. They are deeply afraid of the world that bitcoin threatens to bring about. They prefer a paternalistic, easy-money regime, where occupations like punditry are profitable. Bitcoin promises accountability and a hard money standard. It threatens the existence of bailouts, moral hazard, and fiat-inflationism. In Bitcoinland, the only way to acquire wealth is to work for it. Cronyism doesn’t work, as the central bank of bitcoin is entirely indifferent to politics and lobbying. This offends the sensibilities of the partisans writing for the Post.

Bottom line, the central premise of the article is wrong:

“There’s one thing a currency is supposed to do that bitcoin never has. That’s maintain a stable value.”

Bitcoin isn’t designed to have a stable value. That just quite frankly isn’t what Satoshi set out to build, and that’s not the system we have today. Artificial stability — shorting volatility — leaves you destined for a blowup. That is the fate of any non-fully-backed stablecoin. Bitcoin is designed to solve the double spend problem for digital cash, and to provide a predictable monetary policy. It does that very well, it has done that for the last nine and a half years, and it will continue doing that for the foreseeable future. Demanding low volatility on top of that is farcical, and betrays deep ignorance about the tradeoffs inherent in monetary systems, and the way that financial markets work more generally.

Bitcoin is still an emerging, youthful asset. It hasn’t reached maturity. It has somewhere in the realm of 50–100 million holders/users; that’s global penetration of a percentage point or two. The base layer still hasn’t been nailed down, let alone the next layers up on the stack. Development is deliberate and careful, because this is money we’re talking about, not a consumer app. Governance is hard to organize; consensus is difficult to obtain. The internet wasn’t built in a day, and neither will the protocols for transmitting value trustlessly.

Since the market is constantly revising its expectations for bitcoin, amid a backdrop of growing, unsteady adoption, its exchange rate is volatile. No one is forcing you to hold it; it is totally opt-in. Bitcoin may not make sense for Westerners who live under somewhat credible monetary regimes, but it might be a good bet for an Iranian, a Venezuelan, a Turk, or anyone else who mistrusts their monetary authorities. Truthfully, mechanisms to bring bitcoin to these disempowered groups are still lacking or nonexistent. But they have the right to money that isn’t controlled and minted by a hostile state. This is why bitcoiners work to make global access to this economic institution a reality.

Bitcoin’s complexity doesn’t acquit these pundits for getting simple facts about bitcoin blatantly wrong. And ultimately, their ignorance hurts their bottom line. Being amateurishly wrong about basic details of a system that is widely-understood undermines their integrity and makes readers question their work. The Post’s owner Jeff Bezos should understand this and demand more from his employees.

I f any of this resonates with you, and you want to learn about this novel economic system, here are some sources I recommend for a better understanding of bitcoin:

- Coin Metrics: no-nonsense open data and charting platform informing users about the actual usage of cryptocurrencies (full disclosure: I am a Coin Metrics cofounder)

- Bitcoin Visuals: charts and visuals relating to bitcoin and the Lightning network

- Jameson Lopp’s list of Bitcoin resources

- “Bitcoin’s Academic Pedigree,” Arvind Narayanan and Jeremy Clark

- BitMEX research: long-form investigations into bitcoin economics, the Tether mystery, and market dynamics

Thank you to hasufly and Larry Sukernik for their feedback.

Bitcoin’s Existential Crisis

Cryptocurrencies lack leaders — they have no single source of truth. Philosophically, this can get complicated.

By Nic Carter

Posted October 31, 2018

Identity is a troublesome thing — for humans, nonliving systems, and objects alike, especially as they change over time. Humans can rely on essential traits like DNA to serve as stable markers of identity, and nonliving systems (corporations, for example) can rely on governments and legal systems to anoint them with stable identities.

Cryptocurrencies and public blockchains, though, have no such privilege. They aim to decentralize their leadership without relying on a single third party in establishing their identity. Instead, they rely on subjective social- and economic-consensus mechanisms. While some cryptocurrencies use foundations or corporations to resolve disputes and arbitrate core issues of identity, that’s a fragile approach and generally not consistent with the objectives of these systems.

The most sustainable approach for cryptocurrency is to dispense with the kingmakers, bite the bullet, and leave it to intersubjective consensus. This requires a commitment to a set of practical values that constitute the essence of the system. Systems with more internal consistency and more universally agreed upon value sets are better equipped to last.

The Ship of Theseus Paradox

A classic question-of-identity paradox goes like this: The Greek hero Theseus asks his crew to rebuild his travel-worn boat, and they replace it plank by plank. When the task is done, he ponders whether his restored boat is really the same boat as before, given that all the parts have been replaced. He further considers that if he were to ask his crew to build a new boat with the planks of the old one, two boats would both have a credible claim to being his old vessel. But which is the true original?

It’s compelling because there’s no clear answer. The story shows us that the identity of an object isn’t absolute — it’s assigned, rather than essential.

This comes up even in human contexts: Your cells replace themselves so often that the present you shares very little physical matter with the version of you that existed a decade ago; prisoners held for violent crimes are paroled with the assertion that they have become “a different person” in some vital sense; or — perhaps the simplest example — you might at some time have credibly apologized the day after an intoxicated argument by asserting, “I wasn’t myself last night.” In all these cases, the person is clearly the same person in one sense of identity, but in another sense, many of the traits that make up the person are mutable.

This is okay because the systems that depend on humans to have stable identities can account for the fact that personalities, memories, and physical selves change over time. On a day-to-day basis, our friends and family recognize us, even with decades-long gaps. Low-stakes identity challenges can depend on the recall of certain things we know about ourselves — Social Security numbers, passwords, birthdays, mom’s maiden name, or the name of your first pet. And high-stakes identity challenges can depend on physical markers like fingerprints, retina scans, or DNA tests.

If you build a system meant by its very nature to dis-intermediate third parties and exist independent of governments and legal systems, then you have a problem.

But those human identifiers all rely on the involvement of third parties. And, similarly, certain nonliving systems can use third parties to establish their sense of identity. Creating legal entities like corporations solidifies abstract, malleable sets of individuals and ideas and gives them persistence over time, even if their staffs and business models change entirely. And granting legal assignments like trademarks or patents gives ideas and concepts persistent identity as well as gives their owners exclusivity.

Most nonliving things don’t have these kinds of third-party tiebreakers, though, making them especially vulnerable to Theseus problems. If you build a system meant by its very nature to dis-intermediate third parties and exist independent of governments and legal systems, you have an identity problem. And that problem is one public blockchains face.

The Theseus Problem of Blockchains

While I do not much like the term “blockchain,” I’ll use it here for simplicity. What I am referring is not enterprise blockchains but rather open and permissionless systems like Bitcoin or Ethereum. These two blockchains, in particular, have suffered severe crises of identity over the years.

For Bitcoin, its crisis turned on whether it should attempt to scale up as a P2P payment network immediately (and raise throughput) or whether it should pursue a layered approach. Ethereum had to contend with a reckoning in which participants had to determine their desired level of immutability in response to the DAO exploit.

Both sides had credible cases. There was no constitution that specified, one way or the other, that Bitcoin’s blocksize was permanently capped or that Ethereum couldn’t use a hard fork to reverse (ostensibly) illicit transactions. (Ethereum has a formal specification, but that is a more technical rather than constitutional document.) Instead, there were messy processes of social-consensus formation, appeals to authority, deep readings of original documents, and, ultimately, rancorous splits.

These are not incidental problems or one-offs; they are a core feature of decentralized systems. Public blockchains like Bitcoin, with no recognized leadership, are exposed to competing views of what they are and should be. In a previous post, Hasu and I made an effort to chronicle those disparate visions over time. For sure, there are developers, entrepreneurs, thinkers, miners, and capital allocators who wield disproportionate influence in Bitcoin, but no single individual or institution exerts unilateral control. Therefore, divergent views of the protocol cannot simply be quashed.

Two Approaches to These Problems

How do we cope with this? There are two ways: One is expedient and the other is more sustainable.

The first and most common method is to give a corporation or foundation rights to a trademark, as is the case with Tezos or EOS.IO. This is the default for non-Bitcoin blockchains and gives an entity the legal force to anoint and ratify a single chain. Of course, no one is bound to follow this, and there could be a fork of Tezos that everyone mutually agrees to use.

However, the trademark carries certain legal protections, and if a fork tried to retain the name, the trademark owner would have recourse, at least where the fork tried to interact with regulated institutions. In this case, the trademark is just one manifestation of the core issue, which is confirmation that the leadership of a blockchain is seeking authoritative ratification of their control. Other activities this entity might engage in would be pressuring exchanges to use one ticker over another or support one fork over another as well as spreading a consistent message to the media. All of these give the entity de facto control over which fork is chosen in a dispute.

Consider just how little persistence Bitcoin’s components have. The entire codebase has been reworked, altered, and expanded such that it barely resembles its original version.

The other approach is to throw caution to the wind and spurn any external marker of identity, relying instead on an intersubjective consensus, such that the system can change over time while remaining faithful to its original goals. This is the approach leaderless (or, more accurately, leader-minimized) systems like Bitcoin and Monero go for. Of course, there are influential individuals in both systems, but neither has a foundation or corporation in control of a trademark or a clear decision-making body. Many critics would say that Bitcoin Core, as the author of the dominant implementation of Bitcoin, wields disproportionate control, but that’s a reductive reading. It is not an official body, and the dominant implementation that they create does not define the essence of Bitcoin but rather its instantiation. Pierre Rochard puts it well:

Bitcoin’s block and transaction validity rules are a social consensus that is automated with software. Where they diverge the software is wrong. This is an uncomfortable reality for proponents and detractors alike.

This concept deserves formalization and a lengthier treatment, and I will cover it in a more detailed manner in a forthcoming post.

To pause for a second, consider just how little persistence Bitcoin’s components have. The entire codebase has been reworked, altered, and expanded such that it barely resembles its original version. Core features like multi-signature transactions and pay to script hash have been added over the years, and the protocol only loosely resembles the system described in the white paper — which itself is not a constitution but rather an introduction and teaser. None of the original nodes from 2009 are still running (to the best of my knowledge). Mining has become industrialized and has virtually nothing in common with the hobbyist mining of the early days. The leader has left, as have many of the early developers and stewards of the system, and new sets of developers have sprung up in their place.

The registry of who owns what, the ledger itself, is virtually the only persistent trait of the network, but the ability to copy it at will means it can be splintered. The Bitcoin Cash fork copied the UTXO set and started a new history while retaining the old balances. So it is largely trivial to copy the history and make a claim to the name. Indeed, this was exactly the strategy employed by Bitcoin Cash proponents — strident appeals to Satoshi Nakamoto’s vision.

To be considered truly leaderless, you must surrender the easy solution of having an entity that can designate one chain as the legitimate one.

Their argument was, in effect, that Bitcoin Cash more closely recaptures the essence of Bitcoin. Bitcoin may own the name, but we are closer to the system as intended by its creator and, hence, the true heirs. And they were free to do this because Bitcoin has no foundation, corporation, or entity that sets policy and lives entirely outside of the government, which ultimately adjudicates decisions like these in more conventional contexts. The Bitcoin/Bitcoin Cash struggle was so bitter precisely because there is no single entity that can anoint a true Bitcoin, so it had to be fought in the market, in the media, and in the minds of proponents.

Many critics identify this struggle as a shortcoming or flaw of a distributed system and propose alternative mechanisms to adjudicate disputes. Whether these will work are an empirical matter, but ultimately, the tradeoff remains. To be considered truly leaderless, you must surrender the easy solution of having an entity that can designate one chain as the legitimate one. Political consensus as to the true, genuine protocol must be continually sought and found. Without a stable identity, the system is guaranteed to splinter into pieces.

One Solution to Leaderless Identity

How can you have persistence of identity in a distributed, leaderless system? The cheap solution of having a single entity take de facto or de jure control is unavailable in this context. In fact, the answer is already quite established, although it hasn’t been much discussed. The way that Bitcoin has survived a decade of identity crises, absent any single leader, is this: It has a robust and mutually understood set of ideals that constitute the essence of the system.

The stronger the consensus around these shared ideals, the easier warding off competitors and resisting fragmentation becomes. Additionally, the market mechanism of pricing forks (sometimes prior to their birth through futures) enables individuals to receive powerful informational signals about what their peers are intending to do, which propagates consensus-forming signals efficiently.

During the Bitcoin Cash fork, the core question was whether Bitcoin is a protocol for small, P2P payments at the expense of node operators or a system for cheaply verifying P2P payments at the expense of expediency and short-term scalability. The resounding answer (although some still disagree) was the latter.

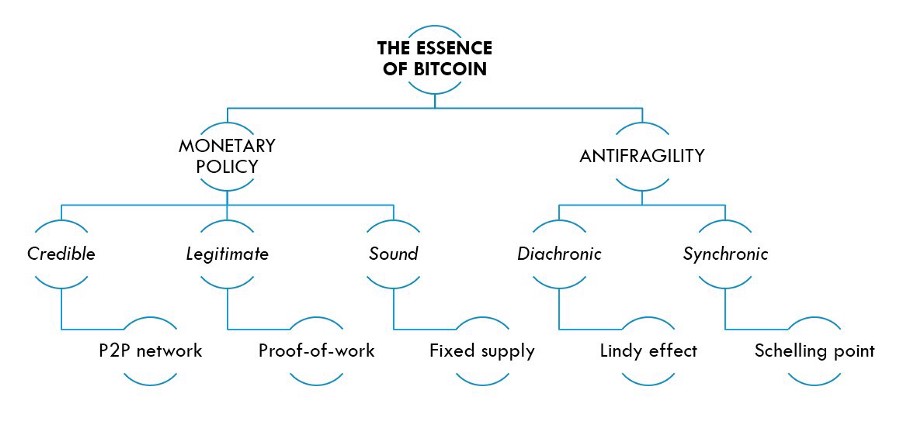

The challenge is that these rules cannot be “found” anywhere. Much like the U.K.’s government, there is no single written constitution. The rules aren’t in the white paper, which is incomplete in many respects. They aren’t exclusively in Satoshi’s writings on the mailing list or the forum — and given his departure after two years, Satoshi sought to resign from the position of ultimate arbiter anyway. The system is best described by the original codebase, although that has changed over time. More fundamentally, the core values of Bitcoin are an intersubjective agreement around a few concepts. David Puell makes a credible attempt to capture it here:

Source: David Puell

Source: David Puell

In fact, codifying and refining these rules is our challenge. By leaving, Satoshi left that task to us. Consistently define the protocol, give it a soul, and let it grow and adapt while being true to its original essence. This is an ongoing challenge, and we learn more and more about its essence with each passing battle, hostile fork, and attempted corporate takeover.

Ultimately, the commitment of the Bitcoin community to these ideals may represent a source of risk. Absolute commitment to the sound monetary policy (the 21 million hard cap) is a core virtue of Bitcoin but limits its design space and ability to pivot if the fee market doesn’t work. But this is the tradeoff Bitcoin has opted for. Other protocols instead sought a more malleable set of core values, relying instead on appointed institutions or well-defined leaders to designate the path forward. The more corporate and top-down these are, the less they rely on a shared identity; in other words, they become empty and soulless. I don’t believe there’s any substitute for diving in at the deep end and relying on essence rather than top-down decrees.

Toward a Bitcoin Ontology

In its 10th year, Bitcoin continues to struggle with these metaphysical issues. It suffers from more existential crises than a philosophy undergrad reading Kierkegaard for the first time. And the reason is that Bitcoiners are strongly opposed to a clear hierarchy for decision-making in Bitcoin. The lack of a benevolent dictator or philosopher king for Bitcoin is held as a strength, even if that makes decision-making less efficient.

In this context, it is not only difficult to forge consensus on key technical issues but also to organize the expenditure of political capital to actually implement those changes. The dispersion of decision-making power and the lack of a unified developer entity is the “problem of governance” that Bitcoin is said to suffer from.

But, here, the disease is also the cure. Bitcoin’s lack of governance is what makes it interesting. It’s a set of rules for moving money around that is very difficult to influence in any way whatsoever. Other open-source projects have benevolent dictators, but in a high-stakes game where the developers can serve as kingmakers for how resources are allocated in society, it’s wise, in my view, to make interfering with the protocol as difficult as possible. Of course, development occurs, but certain core attributes are walled off and considered largely untouchable.

As for the problem of a stable identity, absent a single foundation that maintains the trademark, Bitcoin must make do on its own. In practice, users, exchanges, miners, businesses, and developers engage in an ad hoc, socio-political process of adjudicating between competing visions of Bitcoin.

I expect this debate will end with three divergent philosophical stances within the Bitcoin camp, although it has implications more generally:

First, you have what I call “essentialists” and “materialists.” Essentialists, like myself, believe that the actual code is just a representation of some more fundamental values that the code is trying to express. Essentialists are amenable to rollbacks if something goes wrong in extreme cases because, at that point, the code will have been a poor expression of the form and can be overridden.

I expect there will arise a rival camp of materialists who believe the code is supreme and, in fact, represents the actual substance and reality of the system. Materialists are fond of saying things like “Bitcoin Core is Bitcoin.” They don’t buy the argument that Bitcoin Core is just an implementation of a more nebulous, uninstantiated specification. They often believe that the creators of Bitcoin Core control Bitcoin more generally.

Just as certain Supreme Court justices are strict constructionists and other justices are loose constructionists, it is the same with Bitcoin.

Leaving materialism aside, essence and essentialists — in practice — come down to differing interpretations of the written materials that Satoshi left us, the broader cypherpunk canon, and subsequent empirical findings (such as asserting that the SPV scaling model Satoshi described doesn’t work). Just as certain Supreme Court justices are strict constructionists (believing the Constitution must be interpreted as written) and other justices are loose constructionists (believing the Constitution is a living document that we have to interpret in context), it is the same with Bitcoin.

So, further stratifying the essentialist camp, let’s call the white paper enthusiasts “intentionalists” and their opponents “anti-intentionalists.” Intentionalists tend to think Satoshi’s vision was scaling on the base layer while anti-intentionalists tend to think Satoshi’s precise vision is irrelevant and that what matters more is the system he gave us and its evolution over time. Note that anti-intentionalists are still essentialists. They believe that Bitcoin should be able to adapt while remaining true to its essence but that its exact instantiation doesn’t have to be true to the original specification.

Labels can be dangerous, and excessive labeling is usually not very useful. But these three factions — materialists, intentional essentialists, and non-intentional essentialists — are what I’ve identified, and I think making the lines clear will help us clarify any debate.

The last year has been a period of relative respite in the war over Bitcoin’s soul. However, the battles will continue. This is the nature of the system; it cannot possibly be another way.

Building a fundamental piece of technology that will bring Bitcoin to the next billion users? Reach out: castleisland.vc

Unpacking Bitcoin’s Assurances

Dis-aggregating the system’s guarantees

By Nic Carter

Posted Jan 13, 2019

It has rightfully been pointed out that Bitcoin’s decentralization is but a means to an end — censorship resistance. This is in response to the decentralization fetishism that has characterized Bitcoin competitors and the blockchain industry in general. This is an appropriate response: cosmetic network decentralization is probably not sufficient if you plan on breaking any serious rules, and irrelevant if the industry you are seeking to disrupt is dentistry.

Bitcoin’s fault-tolerant architecture was designed to survive extreme duress, and its multi-variate decentralization was created (or more accurately: emerged) to promote this. However, censorship resistance — the ability to broadcast information without restriction — does not fully cover the guarantees that Bitcoin provides to users, although it is perhaps the most significant.

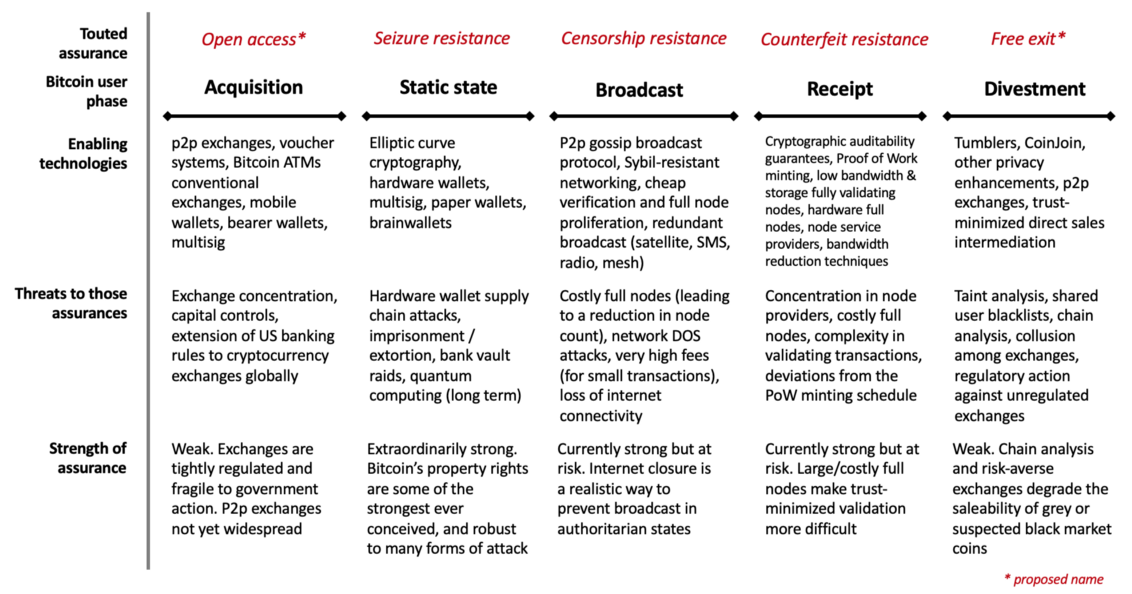

In this post I will try and define the various guarantees that Bitcoin users can expect by taking advantage of the system’s features over the entire usage lifecycle — from acquisition to exit. Censorship resistance is central to these but not sufficiently comprehensive. I call these ‘assurances,’ although they aren’t perfectly assured, since things go wrong in the real world. (I’ve been a fan of ‘assurances’ in this context since reading this post.) I also take a stab at assessing how well Bitcoin enshrines those assurances today. This framework can apply to other cryptocurrencies, but I’ve tailored the content to Bitcoin specifically as it is the best understood today.

Bitcoin’s assurances by usage phase

Bitcoin’s assurances by usage phase

Open access

This is the shorthand for “the right to freely acquire Bitcoin.” No amount of decentralization in Bitcoin’s architecture itself can guarantee this. As many Bitcoiners will point out, free access to the asset requires a vibrant and competitive industry of fiat onramps. The existence of quasi monopolists attempting to build regulatory moats in order to raise barriers to entry threatens this. If acquisition of the asset can only occur in a couple large venues, they are not only susceptible to state action, but also liable to collusively deplatform individuals at will. Imagine what happens to the Venezuelan equivalent of Coinbase during a currency crisis: the government trivially shuts it down to preserve its monetary monopoly.

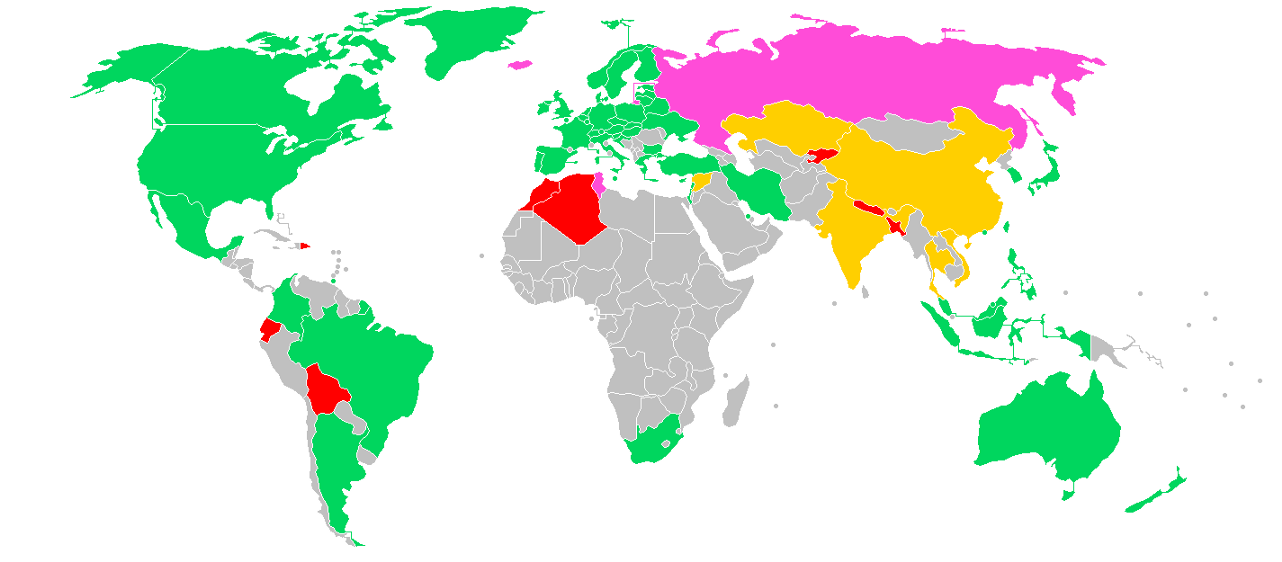

Thus, while large, regulator-friendly, conventional exchanges are good onramps in the developed world, where cryptocurrencies are not (yet) a threat to local sovereign currencies, they aren’t a good fit for states experiencing demonetization or high inflation, which is where access is most impactful. Centralized exchanges must be supplemented by peer to peer exchanges like LocalBitcoins, Hodl Hodl, Paxful — and indeed, they are the venues where trading seems to occur (Venezuelan traders are doing $300m annualized on LocalBitcoins, Nigeria ~$170m, Russia close to a billion USD). Wallets which allow for trust-minimized trading like Opendimes are vital here — receiving an Opendime where you can be sure your counterparty doesn’t know the private key beats waiting an hour for six confirmations.

Lastly, paper voucher systems enabling users to acquire smaller quantities of Bitcoin at street kiosks or from corner shops are an important piece of the puzzle. Vouchers work by exchanging fiat for a receipt with a code on it; settlement can be done later. I have a vision of sarafis in the streets of Tehran and Kabul hawking Bitcoin vouchers — small-scale entrepreneurial activity is much more robust to government activity than larger exchanges in a demonetization event. Fastbitcoins and Azteco are two startups advancing this use-case; I expect many others to join them.

Peer to peer exchanges like Hodl Hodl rely on a crucial and unheralded technology: Bitcoin’s native multi-signature (multisig) capability. A simple, well-understood, trusted, and widely-used multisig implementation enables massive secondary benefits. In the case of Hodl Hodl, it allows buyers and sellers to transact with a high degree of confidence that they will not be cheated. In 2-of-3 multisig contract, the seller and buyer must both sign the release transaction; and if one disagrees, it is referred to the arbitrator for a decision. In practice, the vast majority of transactions settle without arbitration — the threat of mediation itself enforces good behavior.

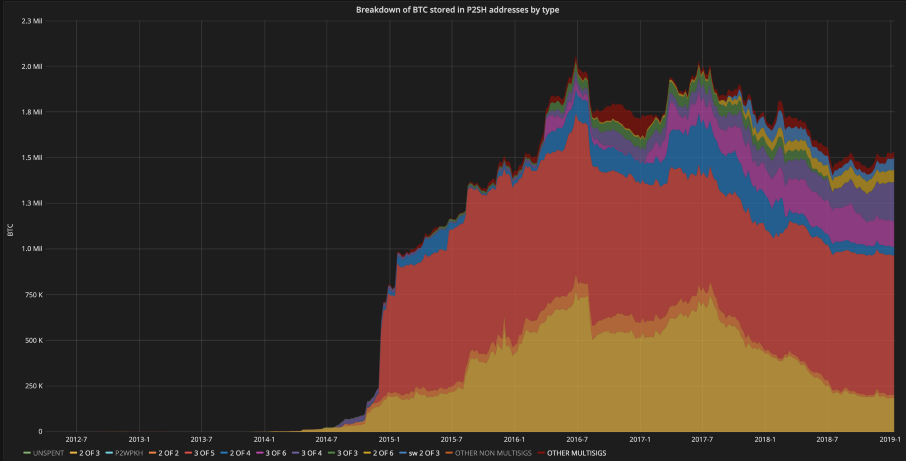

Multisig is popular in Bitcoin today: about 1.65m BTC (about $6b) are held in known multisig wallets. This figure climbs to 3.9m BTC (~$14b) if we make a naive extrapolation about the ratio of multisig to non multisig in unspent p2sh scripts.

Source: p2sh.info

Source: p2sh.info

To sum up, open access to Bitcoin is a core component of the system — what use is the asset if you can’t easily obtain it? — yet it is somewhat overlooked. It’s important to be realistic about this. Bitcoin suffers from a paradox whereby individuals in countries with relatively less need for Bitcoin have frictionless access to it, while individuals dealing with hyperinflation have to reckon with a less developed onramp infrastructure. There is much work to be done here.

Seizure resistance

One of the chief motivations for this article was to differentiate the unencumbered broadcast rights that Bitcoin grants users from the strong guarantees it grants to users when it is at rest. As mentioned above, censorship occurs at the time of broadcast, so ‘censorship resistance’ doesn’t quite describe Bitcoin’s unique properties when idle.

Thus the inclusion of seizure resistance(this is also sometimes referred to as ‘tamper resistance’ or ‘judgment resistance’). By this I mean the ability of users to retain access to their Bitcoin under duress, during times of upheaval or displacement, all in a peaceful and covert way.

As Hasu and Su Zhu have eloquently written, Bitcoin can be understood as an independent institution which provides users property rights which are untethered from the state or the legal system. As virtually all property rights trace back to the state, the legal system, or some local monopoly on violence, Bitcoin’s cryptography-based property rights are a genuinely new paradigm.

This has been covered at length, but the fact that individuals can store their wealth in a 12 or 16-word passphrase held in their memory is quite astounding. While that’s not the most failure-resistant way to operate, it makes one’s wealth extremely portable and concealable.

Multisig also comes into play here. Innovative custody companies like Casa (disclaimer: Castle Island is an investor) rely on a 3-of-5 multisignature setup whereby the user controls four keys physically dispersed, and Casa holds one for disaster recovery. This makes physical attacks on Bitcoin holders much more difficult and expensive, while preserving convenience and resilience to faults (seedless recovery is possible if a hardware wallet is lost). The secure key sharding that Bitcoin offers fundamentally reinvents what it means to be a custodian, and opens the door for all kinds of innovative hybrid models which offer various resilience/autonomy tradeoffs.

Censorship resistance

This is the most celebrated assurance attributed to Bitcoin, so I’ll be brief. At its core, Bitcoin allows permissionless broadcast through the p2p gossip protocol and the miner fee incentive. Anyone can make a transaction, although they have to sufficiently compensate a miner to include it in a block. If there is a lot of traffic, this could entail a delay or a higher fee. The other required component here is a well-connected network of nodes available to route transactions. If full nodes were to become very expensive and difficult to run, full node counts might decline, making broadcast more difficult. That said, node counts would have to drop precipitously to impair network performance, so this isn’t an immediate concern.

One realistic impairment to censorship resistance is the simple approach of simply shutting off local access to the internet. While Bitcoin’s global infrastructure cannot be realistically held back by even by the most motivated state actor, a state under severe monetary duress — experiencing a demonetization event, for instance — might take the extreme step of temporarily restricting access to Bitcoin by shutting off the internet. In recent memory, governments in Iran, Turkey, and Russia have shown themselves willing to exert massive collateral damage on local internet access to target services like Telegram and Wikipedia. Places like China where the internet and Bitcoin usage are already tightly regulated would be well-positioned to impose such restrictions. It’s not inconceivable that a state could attempt to target Bitcoin in such a manner.

Touted mitigations to state censorship of Bitcoin’s broadcast layer include Nick Szabo’s long-range radio proposal as well as Samourai/Gotenna’s SMS and short-range radio mesh proofs of concept. These initiatives, however, are still either in the R&D phase or the very earliest phases of deployment. At present, individuals in internet-restricted locations have little recourse when faced with such an attack, aside from physically getting their funds out of the country in a hardware or paper wallet. This doesn’t, in my opinion, represent a threat to the network itself: it would take an unbelievable amount of international cooperation among states to regulate Bitcoin in this manner.

Network DOS attacks through fee spam are also an effective if costly way to make it more difficult for everyday users to broadcast transactions. There are few mitigations for this aside from waiting out the attacker or outbidding them.

Counterfeit resistance

This is a crucial quality of the system, and yet it doesn’t get quite the rhetorical exposure that censorship resistance does. Counterfeit resistance is simply the idea that individuals who use Bitcoin have very cheap access to the tools required to verify that payments they are receiving are legitimate, that their savings have not been debased through inflation, and that their counterparties aren’t cheating them in some way.

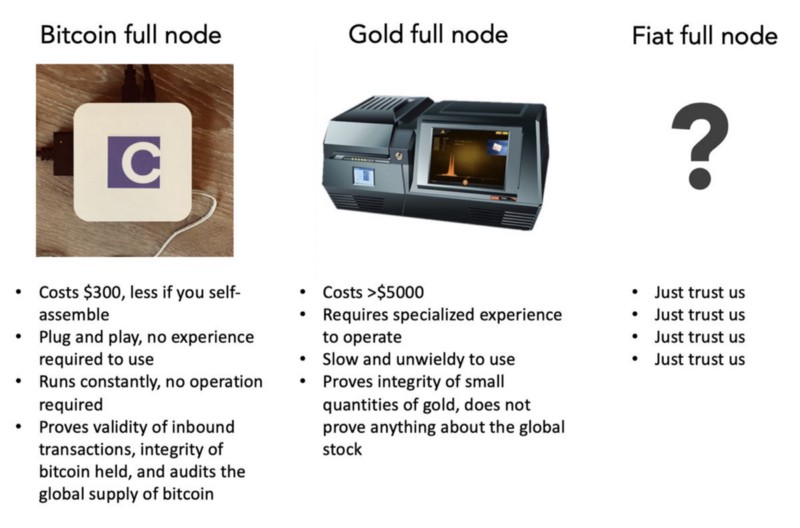

Comparing Bitcoin to gold, the ability to run a full node is akin to owning a professional-grade XRF spectrometer to check the integrity of your bullion. Compared to the expensive and tricky tests to verify gold’s authenticity, verifying the integrity of one’s Bitcoin is a breeze. Running a node costs a few dollars a year and can be done on consumer hardware and bandwidth with little difficulty. This very accessible counterfeit resistance only persists as long as running a node is relatively cheap — a significant increase in the bandwidth, computation, or memory required to run a fully validating node would hinder it significantly. Right now, Bitcoin is growing at a stable rate, and physical plug-n-play node hardware has made full nodes more accessible than ever, so this assurance seems safe for now. For individuals and enterprises that don’t want to run nodes directly, a good diversity of managed node software exists.

The other side of counterfeit resistance is the ability to determine that all units that exist were created according to a predefined, predictable schedule. The proof of work minting function, plus the difficulty adjustment, takes care of this. Well — close enough. Naively assuming that blocks were meant to arrive every 10 minutes on average, Bitcoin is actually slightly ahead of schedule by 30,000 blocks or so. This is because hash power has generally increased over time, and this caused block arrival to outpace the defined schedule due the coarse granularity in the difficulty adjustment. Aside from this interesting emergent property, Bitcoin’s PoW has never been compromised, nor has the hash function been broken (and this doesn’t seem eminently likely in the foreseeable future). Verifying that the correct number of units exist is as simple as running the gettxoutsetinfo command in your Bitcoin Core node. The inherent auditability of Bitcoin and all of its derivatives is what makes deceptions like the Bitcoin Private covert inflation scandal easy to spot.

At present, Bitcoin’s counterfeit resistance is made possible by a deliberate design philosophy from the core developers that prides accessibility and user self-sovereignty at all costs. It is augmented by a network of Bitcoin businesses that provide hardware nodes or managed access to node software. However, if the chain’s growth were to radically accelerate, consumer-grade counterfeit resistance would be significantly impaired.

Free exit

Free exit — the ability to sell Bitcoin unencumbered — is another aspect of the system that is sometimes overlooked. It’s not strictly a Bitcoin guarantee, but Bitcoin’s usefulness is significantly downgraded in its absence. The real world consequences of overzealous chain analysis companies (whose heuristics implicate innocent users through false positives) make themselves felt when those users attempt to sell their Bitcoin for fiat. Since fiat offramps are the most easily regulated and are run by risk-averse institutions, they are a natural target for entities that create blacklists and ascribe taint to individual UTXOs.

There are a few strategies to reckon with this. One is to obfuscate the origin of funds through collaborative tumblers like the Wasabi wallet . Another approach is to reverse-engineer the heuristics that chain analysis firms use and develop mixing strategies that implicate everyone in taint (thus rendering those heuristics incoherent) or that avoid detection altogether through specialized transaction types. This is the general approach of the folks behind the Samourai wallet. Routing around the centralized, highly-regulated exchanges is another option, either on the p2p marketplaces or by exchanging BTC for goods and services, rather than fiat.

Ultimately, I expect that a tranche of grey or black-market Bitcoins will emerge, with coins available at a discount in exchange for their reduced access to capital markets. This will not be a death knell — there will likely be more than enough demand globally for slightly cheaper Bitcoins, even if they cannot be traded on Coinbase. The world is a big place, with a variety of regulatory regimes, and individuals fleeing hyperinflation may not be too bothered by the fact that the Bitcoins they acquired cannot be deposited on US-regulated exchanges.

The objective for this piece was to present a framework of the major assurances that Bitcoin provides to users, and make it clear that censorship resistance is only one of them. Additionally, I wanted to make the point that Bitcoin the software is only one part of a much vaster system — a collaborative social and industrial project aiming to provide unencumbered financial tools to individuals the world over. Entrepreneurs that have created hardware wallets, merchant services, novel exchanges, voucher systems, Bitcoin contract structuring, and hybrid custody models have all done their bit to advance user sovereignty and discretion when it comes to their personal wealth. They deserve to be recognized, as does the broader struggle to make these touted assurances a reality.

How to scale Bitcoin (without changing a thing)

Why Bitcoin banks need to prove their solvency

By Nic Carter

Posted April 14, 2019

Almost from inception, the “scaling debate” in Bitcoin, and cryptocurrency more generally, has been framed in what could be called Hegelian terms.

- Thesis: peer-to-peer cryptocurrencies are useful for online commerce

- Antithesis: online commerce requires millions of transactions a day

- Synthesis: to succeed, cryptocurrencies must scale

This has been the default backdrop for discourse in the industry and the onlooker press for the better part of the last decade. In this piece I’ll posit that this obsession, which has driven discourse in Bitcoin land for the better part of a decade, misses the point, and I’ll suggest an alternative framing. I believe that institutional scaling presents an under-appreciated scaling vector, and it is quite possible to employ it without significantly compromising Bitcoin’s assurances.

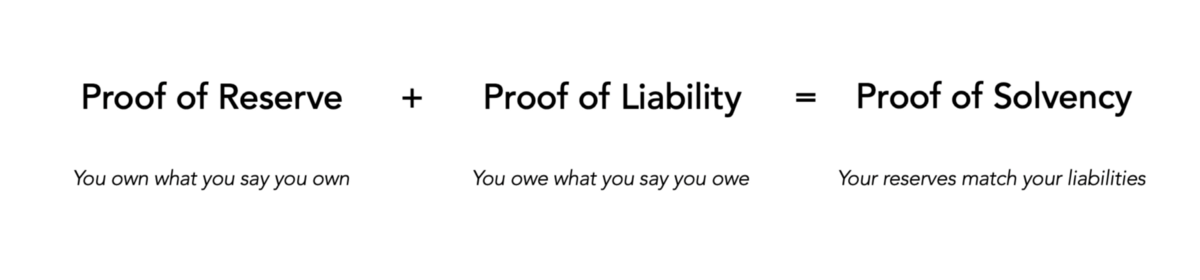

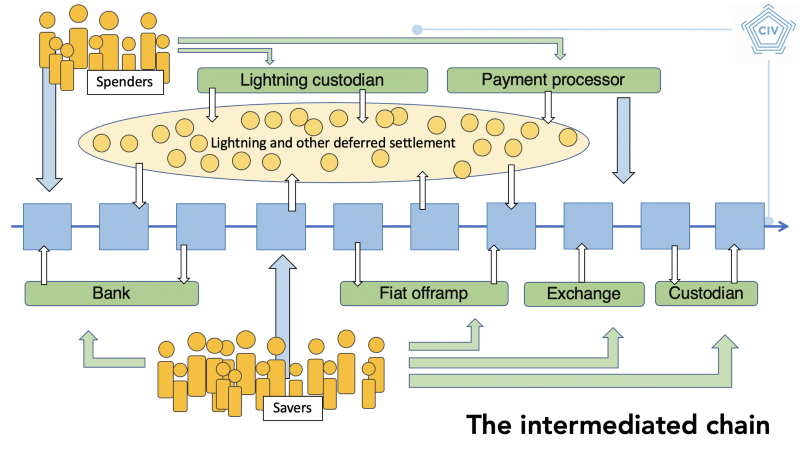

By this I mean the Finneyan view of Bitcoin in which Bitcoin banks emerge and issue notes against deposited Bitcoin. If you look carefully, a proto version of this system is in place today. However, for cherished assurances like scarcity to be upheld, exchanges and custodians need to start making routine attestations that their reserves match their liabilities.

Before we start, a tiny literature review (optional):

- Spencer Bogart on Bitcoin’s strong assurances

- Hasu on how Bitcoin supports non-state property rights

- Yours truly on the quality of Bitcoin’s touted assurances

- Jameson Lopp on the exact technical guarantees and near-guarantees that PoW gives you

- Davidson, De Filippi, and Potts on how public blockchains are a new type of institutional technology

- Saifedean Ammous on how Bitcoin could function solely as a settlement network

Prescience on the mailing list

The very first public comment on Satoshi’s white paper, coming as a response on the cryptography mailing list five hours after publication, was this astute observation from James A. Donald:

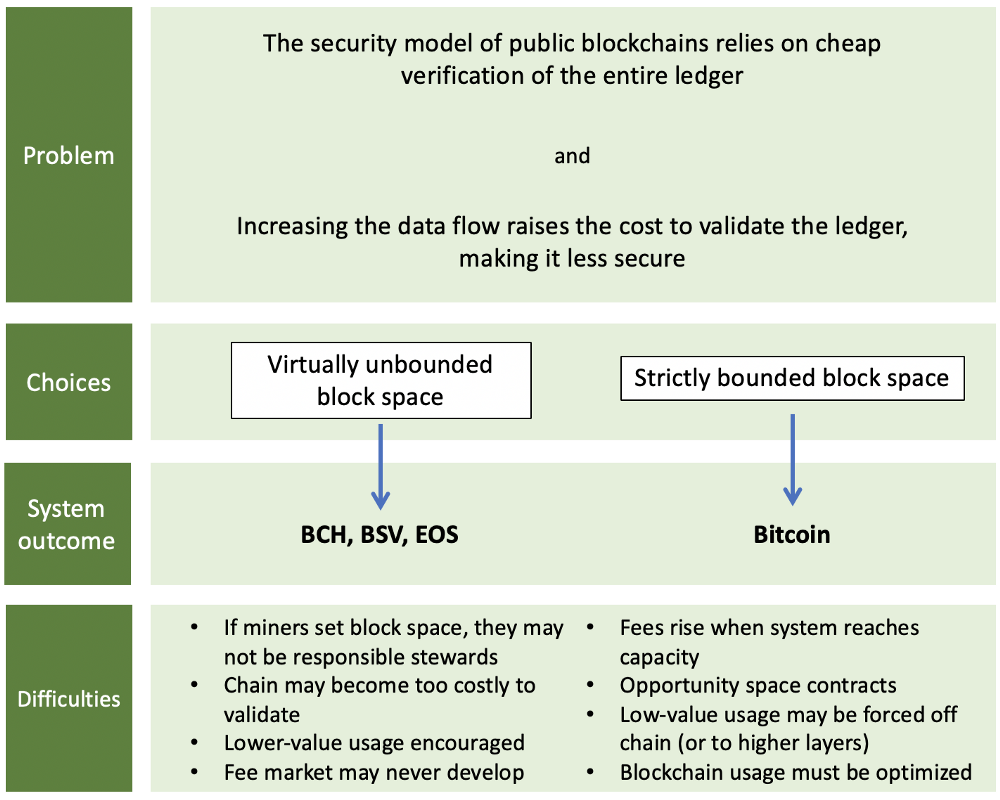

If hundreds of millions of people are doing transactions, that is a lot of bandwidth — each must know all, or a substantial part thereof.

What James understood is something that has escaped many who scampered down terabyte-block rabbit holes: Bitcoin only works because anyone can retain a copy of the ledger and stay in sync. If you make syncing with the current state of the ledger too expensive, only a privileged few can stay up to date, effectively adding a hierarchy to a system which must be flat to function.

Satoshi’s answer to this question, interestingly, involved SPV proofs, which, bathed in a present-day epistemic light, appears somewhat naive. SPV proofs ostensibly allow a non-full node to know that a transaction has been included in Bitcoin without downloading the whole chain. Casually invoking SPV proofs as the solution to scaling is a bit like the scientists behind the Apollo program remarking: “Oh, a trip to Alpha Centauri? Just the simple matter of faster than light travel.”

Suffice to say, SPV proofs have been virtually abandoned as a viable scaling method today. Under a variety of scenarios, they tend to collapse into users having to validate the entire chain anyway.

James was spot on. He immediately understood that Bitcoin was a single ledger which all of the nodes in the network had to continuously reaffirm at 10 minute intervals. Since everyone had to see everything, hundreds of millions of transactors would simply overwhelm the system.

But what if this teleological premise — Bitcoin is for global, online, peer-to-peer commerce at the individual level — was flawed? Enter Hal Finney.

Stairway atop Diana’s Peak, St Helena

Stairway atop Diana’s Peak, St Helena

Hal’s vision

In 2010, digital cash pioneer Hal Finney famously made the case for what could be called the institutional approach to scaling Bitcoin.

Actually there is a very good reason for Bitcoin-backed banks to exist, issuing their own digital cash currency, redeemable for bitcoins. Bitcoin itself cannot scale to have every single financial transaction in the world be broadcast to everyone and included in the block chain. There needs to be a secondary level of payment systems which is lighter weight and more efficient. Likewise, the time needed for Bitcoin transactions to finalize will be impractical for medium to large value purchases. Bitcoin backed banks will solve these problems. They can work like banks did before nationalization of currency. Different banks can have different policies, some more aggressive, some more conservative. Some would be fractional reserve while others may be 100% Bitcoin backed. Interest rates may vary. Cash from some banks may trade at a discount to that from others.

In a brilliant stroke of foresight, Hal understood that base layer Bitcoin would never scale to the desired level in its current format. (Unfortunately, many Bitcoin evangelists failed to understand this, and their misapprehensions led to the bitter blocksize wars of 2015–17.) In Hal’s view, Bitcoin would be a high-powered money mediating large settlements between financial institutions, rather than a payment token used for the online equivalent of petty cash payments. He realized that Bitcoin’s rather slow settlement times (compared to physical cash or credit cards) combined with the inefficiency of the chain itself meant that directing Bitcoin to the brick-and-mortar payments use case was a square peg in a round hole.

What Hal envisioned was a system where banks could be auditable, transparent in their capital ratios, and accountable. A free market for reserve/capital ratios could even develop, as depositors would be able to select banks with varying levels of reserves to suit their risk preference.

Undercapitalized banks might fail — but this would be a healthy market signal, a culling of weaker entities to render the herd stronger overall. Compare this to the system that became unraveled in 2008/09: financial institutions heaping on leverage, knowing that they would be bailed out if something went wrong. Since the government made it clear that it would not allow banks to fail, the market was robbed of that valuable feedback mechanism and risk became increasingly abstracted, obscure, and hidden.

In the words of Elaine Ou:

Financial institutions make people feel safe by hiding risk behind layers of complexity. Crypto brings risk front and center and brags about it on the internet.

In finance, risk never truly disappears, even if hidden — and suppressing it often has the nasty effect of unleashing it in a more dramatic fashion later on.

Just as risk crept up on us, unheralded, and financial institutions failed one after the next in a cascade of toxic balance sheets in 2009, so too will the long-suppressed forces of systemic risk unleash themselves when our present monetary experiment finally unwinds.

Can Bitcoin mollify this? Perhaps not. But its very structure facilitates the creation of an alternative financial system which is far more transparent and open about risk than the present one. This is the Finneyan view of Bitcoin: Bitcoin as a virtual commodity sitting in provable reserves in financial institutions. No one’s liability, a provable virtual commodity which a bank can rely on to attest to its viability.

Winding road through Glencoe, Scotland.

Winding road through Glencoe, Scotland.

Scaling assurances

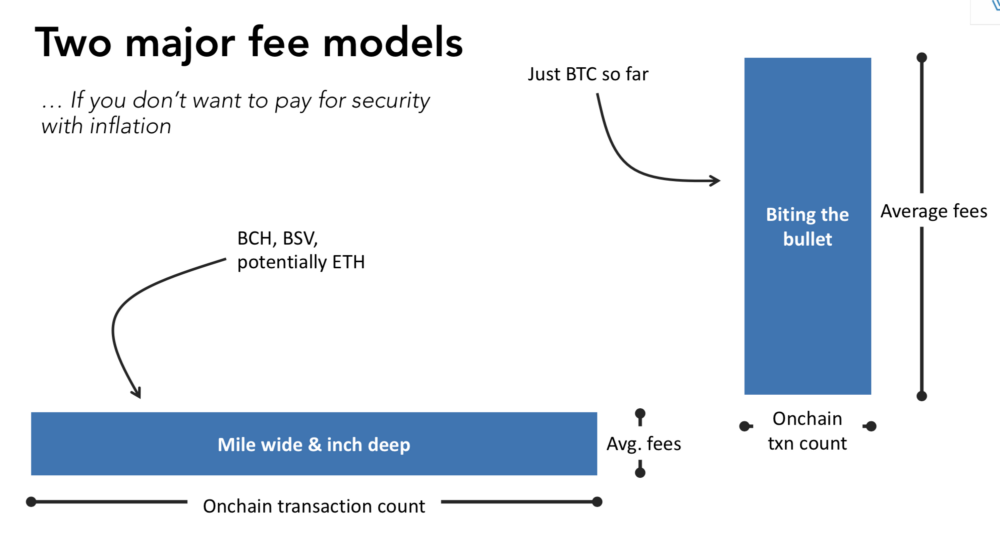

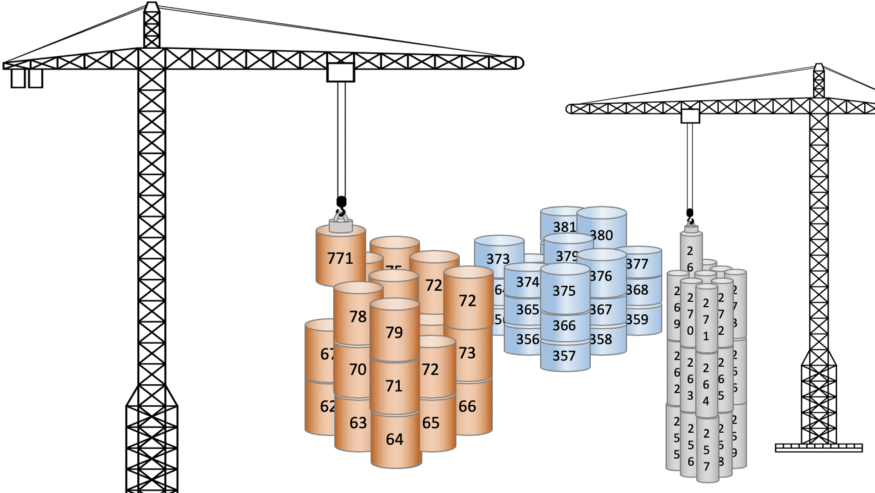

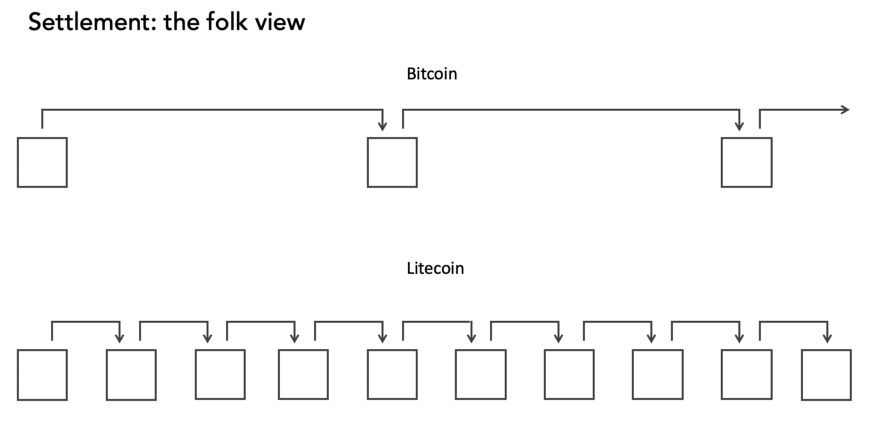

Let’s briefly revisit what we mean by scaling, anyway. It’s clear by now that simply opening up the block space throttle doesn’t work. This is because Bitcoin is designed to be auditable, and auditing the blockchain requires the full, unabridged ledger.

Fundamentally, Bitcoin relies on everyone being aware of every transaction. Can this be scaled without compromising this core feature? Let’s see how the major classes of scaling innovation fare under this lens:

- Deferred settlement/reconciliation(chiefly lightning). What lightning and other defer-reconcile models of transacting do is grant users the ability to create relationships which are then settled at a later date. The chain’s assurances are still present and available, they just aren’t employed for each transfer. These models do however trade off by (temporarily) weakening assurances — final settlement is no longer instant and you have to be online to receive a payment, for instance.

- Database model (massive base layer scaling). As mentioned, simply increasing the ledger size compromises the assurances of the blockchain — not everyone is able to maintain the ledger. There may be a way to do this in a trust-minimized way with SPV and fraud proofs, but we haven’t found it yet.

- Extending assurances to other chains (sidechain, security inheritance, merged mining). This model blesses other block space with Bitcoin’s security or extends Bitcoin’s own block space. Merged mined coins like Namecoin, proof-of-proof approaches like Veriblock, and sidechains like Rootstock are all roughly in the same family of approaches to the problem. These represent a compelling potential avenue to scaling, as they extend Bitcoin’s settlement guarantees to a potentially unbounded block space, but it is still under explored. However, assurance impairment is possible — risks remain that miners might censor sidechain closures or otherwise interfere with the sidechain. The productized implementations that we’ve seen like Liquid have used consortia rather than relying on PoW.

- Trust-minimized institutions. This approach takes the assurances of Bitcoin — natively auditable, scarce digital cash — and applies them in the context of a depository institution. In short, rather than individual users being the clients of Bitcoin, institutions like exchanges, banks, and custodians adopt the end user role, with their own users indirectly benefiting from Bitcoin’s assurances. Trade offs remain, and some features of Bitcoin don’t apply in a custodial context, but if protocols like Proof of Solvency are implemented, some of Bitcoin’s guarantees can shine through, even if filtered through an intermediary.

What should Bitcoin banks look like?

Is Hal’s vision of a world of banks backed by Bitcoin plausible? In one sense, it’s the world we have today, as many users only touch Bitcoin indirectly, through custodians and intermediaries. While most exchanges are presumed to be full-reserve, and indeed generally claim to be, in practice this isn’t universally the case. It’s becoming clear, for instance, that QuadrigaCX was running a fractional reserve for most of its existence. I don’t need to recap the sordid history of malfeasance and negligence at cryptocurrency exchanges.