Mining Centralization Scenarios

| If you find WORDS helpful, Bitcoin donations are unnecessary but appreciated. Our goal is to spread and preserve Bitcoin writings for future generations. Read more. | Make a Donation |

Mining Centralization Scenarios

By Jimmy Song

Posted April 10, 2018

In my article last week, I talked about how Bitcoin is decentralized, that is, lacks a single point of failure or choke point. One of the things many critics of the article pointed out was that mining is somehow centralized and therefore, my argument didn’t hold.

In this article, I’m going to examine mining centralization in depth, go through some scenarios to understand what the risks are, how it could play out and what the implications are going forward.

Defining Mining Centralization

Mining Centralization can mean two different things:

- Manufacturing of mining equipment being mostly in the hands of a single company.

- Majority of hash power being controlled by a single company

These two are different and when someone says “mining centralization”, it’s not always clear which they mean. The rest of the article is organized to examine the risks and possible attacks of each. Note we’ll examine some scenarios here, by no means exhaustive, but they should give a pretty good idea of the possible risks and mitigations of Mining Centralization.

Manufacturing Centralization

Bitmain does indeed produce a majority of double-sha256 (proof-of-work hashing algorithm behind BTC, BCH and a few others) mining equipment and the majority of hash power on the Bitcoin network as of this writing come from miners manufactured by Bitmain. We suppose here that though Bitmain may manufacture a majority of the mining equipment, they don’t necessarily control the equipment.

What are the risks of a single manufacturer producing most of the equipment used to secure the network?

Scenario 1: Backdoor

In this scenario, we assume that Bitmain sells most of the equipment that they manufacture.

The risk here is that Bitmain has put in some sort of backdoor to the mining equipment through some hidden hardware, firmware or software. Some possible things a backdoor could do:

- Force the mining equipment to point to a Bitmain-controlled pool mining whichever coin Bitmain chooses.

- Override the block template to give rewards to a Bitmain-controlled address.

- Throw away valid proof-of-work unless the miner is pointing to a Bitmain-controlled pool.

- Shut down the miner using some predetermined signal. (Kill-switch)

The first two possible back doors would be really obvious to anyone paying the least bit of attention. Furthermore, they would be really obvious to prove with even a little bit of logging. The consequences of the discovery of a backdoor of this magnitude would pretty much destroy Bitmain’s reputation as a company and additionally make it the target of a class action lawsuit at a minimum. This would be the equivalent of a kamikaze attack on Bitcoin, which might hurt Bitcoin short-term, but would completely destroy Bitmain as a Bitcoin ASIC manufacturer.

The third and fourth can be done in a more subtle way, but would still be susceptible to discovery. Throwing away proof of work has the effect of delaying blocks while making the non-Bitmain pool look more unlucky. Using a kill switch disables the equipment. The direct effects of both are actually detrimental to Bitmain as they have to deal with customer refunds and complaints about their miner not working. All benefits would have to be secondary, such as attracting more people to their pool. They also carry enormous risks as competitors might discover such backdoors and utilize them to Bitmain’s detriment. The risk of discovery alone more or less destroys whatever reputation Bitmain enjoys and the benefits uncertain and far off.

Note that these are things any mining manufacturer could put into their equipment. Hardware is very hard to audit and by buying equipment from a particular manufacturer, you’re in a sense trusting them not to cheat you.

In the 4–5 years of existence, Bitmain hasn’t resorted to these tactics, and there’s no reason to think that they would. Such backdoors involve a lot of planning, a high chance of discovery and/or failure and a low chance of reward.

Scenario 2: Manufacturer Defect

This scenario assumes that everything else is the same as scenario 1, but the equipment has some fatal defect. Perhaps the equipment catches on fire above a certain temperature. Perhaps the equipment calculates the timestamp wrong.

The worst possibility here is that the equipment creates invalid blocks and that’s easily seen by the rest of the network. Again, this only hurts the manufacturer, as they are the ones that have to deal with their customers’ anger.

Scenario 3: Price Gouging/Buying Restrictions/Shipping Delays

In this scenario, the equipment manufacturer uses its dominant position to add additional costs for buyers of the equipment. The costs may be charging more for the equipment, forcing the usage of certain payment methods, delaying shipping, perhaps even restrictions on how the equipment may be used.

All of these tactics become intolerable under competition as the total costs of the equipment can’t go above that of the competition without hurting sales and thus must be used judiciously, if at all. The additional revenue from acting this way is offset by long term reputational damage.

Hash Power Centralization

The actual manufacturing of equipment can lead to some bad outcomes, but the more dangerous scenario is one where there is a concentration of hash power. Specifically, one company may control more than half of the hash power on the network.

These can further be subdivided into two different categories:

- One company controls pools totaling >50% of network hash power

- One company controls machines totaling >50% of network hash power

The possible attacks are similar, but the way the attacks can be thwarted are a bit different. If a single entity controls a bunch of pools, individuals that participate in the pool can simply switch to a different pool to thwart the attack. If a single entity controls a bunch of machines, that is no longer an option. Keep this in mind as we go through the possible ways in which a majority hash power entity can attack the network.

Scenario 4: Majority-only chain

One obvious thing the majority hash power can do is simply reject blocks from everyone else, in essence taking every block reward for themselves. They could also deny transactions they don’t like and possibly try to double spend as well.

This is not as easy an attack to pull off as it would seem, just from the math, if the majority is not much more than 50%.

To illustrate why, imagine that a hypothetical manufacturer called Mitbain controls 60% of the hash power and decides to execute the block rejection attack. The probability that the rest of the network finds a given block is 40%. It’s clear that because the minority still has some hash rate, at some point, Mitbain will be behind by 1 block to the rest of the network.

In order to overtake the lead, Mitbain will need to find 2 more blocks than the rest of the network. This is not as simple as it sounds. Given sufficient time with a majority of the network hash rate, overtaking is inevitable, but this does not necessarily happen very quickly.

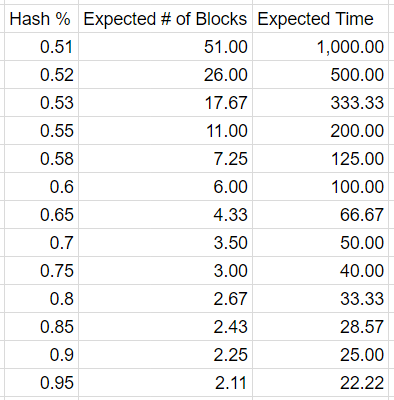

The math is a little involved, but the number of expected blocks until Mitbain overtakes the rest of the network is actually quite high. With 60% of the network hash power, the expected number of blocks until Mitbain overtakes the network is actually 6 blocks! Note this is with 60% of the hash power, so that’s not 60 minutes for those 6 blocks, but 100 minutes.

Not only that, but in the best case scenario for the attacker, the entire network will be invalidating the previous 5 blocks for the attacker’s 6 new blocks. Every transaction that happened in the previous 5 blocks would be invalidated as if they never happened and the transactions in the 6 new blocks seen as canonical. This is what’s called a block reorganization or a reorg for short and is how a double-spend attack can be performed in Bitcoin. Of course, the attacker could be “nice” and include more or less the same transactions as the original blocks that it’s overtaking, but there’s no guarantee.

No rational merchant or exchange would ever take less than 30 confirmations in a scenario like this (at least without some knowledge about what’s going on).

Time is in minutes

Time is in minutes

The above chart shows how many blocks you can expect to reorg every time the rest of the network finds a block. You can see that even having something like 70% of the network hash rate makes executing this attack pretty long and drawn out. If after spending enough hash power to find 6 blocks, Mitbain is still behind by 2–3 blocks, would Mitbain really want to continue?

Furthermore, a large reorg signals to the rest of the network that something nefarious is going on and nodes will likely view these new blocks with suspicion. It’s entirely possible that full node operators on the network will simply invalidate these blocks (this is possible through the invalidateblock command) and happily view the other chain made by the rest of the network as canonical, in which case, Mitbain would have wasted an enormous amount of hash power, announced its bad intentions and have a fork that many nodes don’t recognize for all its trouble. This would be a hard fork without any replay protection and the community would decide which one is worth more.

In addition, during the attack, there are large reorgs every time a non-Mitbain miner finds a block, which make taking payments extremely risky. Essentially, without something like 80% of the network, this attack renders Bitcoin all but unusable during the attack.

If, instead, Mitbain simply mined normally on the network, the mining rewards would essentially be the same without arousing any suspicion or incurring any reputational damage. The double-spend, fee sniping and transaction denial value would have to outweigh the risk of failure including loss of mining rewards, loss of reputation and damage to Bitcoin itself.

To put it simply, this attack really doesn’t make much sense from an economic perspective because there is simply not enough upside for the attacker. What’s more, even if successful, Bitcoin would still survive! There is no guarantee that the temporary degradation of the network is enough to make all the Bitcoin owners sell.

Scenario 5: Turning Off Hash Power

The majority hash power don’t have to attack the network in order to have influence, however. The majority can simply refuse to mine and provide the proportional security for the network. For example, the majority, say 80% of the hash power, can refuse to mine as a way to add political pressure for a certain feature. This would be similar to a hunger strike.

This scenario would cause some difficulties on the network. 10 minute blocks would now become 50 minute blocks. The mempool would probably fill up fairly quickly and transactions would be especially slow. This may, in turn, lead to higher fees.

This scenario is much more expensive for the attackers, however. They are giving up 1437 BTC/day or about $10M/day in revenue at current exchange rates. Even if the equipment were to be utilized on another network, their profitability and opportunity cost would suffer quite a bit.

What’s more, the Bitcoin network confirmation times would recover in a matter of weeks while the lost revenue will never come back for the would-be hunger strikers.

What Majority Hashing Cannot Do

It’s perhaps useful here to recap what a majority of hashing power cannot do.

First, the majority cannot take any coins you already possess away from you. All your coins are yours and the worst an attacker could do is double-spend incoming transactions or deny your outgoing transactions from going through for a while. This is normal and expected as we saw for transactions that didn’t have a high enough fee around December.

Second, the majority cannot change the rules of Bitcoin. In a sense, they can create new consensus rules, but that would be a hard fork, which requires everyone to upgrade. They’re free to try to convince the rest of the network that their rules are better, but as sovereign individuals, Bitcoin users have no obligation to follow such rules. The power of whom to follow lies entirely with the owner of the node.

Third, the majority cannot hurt you without hurting themselves to some degree. Such an attacker can degrade the network, but not without themselves incurring a lot of opportunity cost. They can attempt to double-spend, but not without significant risk of being blacklisted by many nodes.

Bitmain

At least from a manufacturing standpoint, the risks are being lowered continually. As much as people hate Bitmain, let’s not forget what manufacturers existed before them were like. Butterfly Labs, CoinTerra and KnC Mining are just some of the names in this space and they had some serious trouble even filling pre-orders.

Bitmain brought a professionalism to the mining industry that simply wasn’t there before. They were selling fully assembled, ready-to-go miners at conferences in 2014 where these other companies were delaying the delivery of pre-orders from months, sometimes years, before. The competence that Bitmain brought to the mining industry is why those other players are bankrupt.

That said, there is no reason to believe that Bitmain’s market dominance is permanent.

One of many new entrants into the Bitcoin mining game

One of many new entrants into the Bitcoin mining game

First, there is a lot of competition coming. There are no less than 4 startups that I know of that are entering the mining space attempting to dethrone Bitmain. There are also larger companies like Samsung, Intel and Nvidia that are looking into getting into this very lucrative industry.

Second, unlike Bitcoin itself, there is no strong network effect in mining equipment manufacturing. People looking to mine may care a bit about who the machines are manufactured by, but most care much more about how much money they can make. In other words, having bought miners from Bitmain in the past does not lock them into buying more of their products. If anything, many people looking to mine will pay more to get _non-_Bitmain products.

Third, Bitmain is a very large company at this point. They are working on machine-learning ASICs, altcoin ASICs, buying up companies and funding lots of different projects. Large companies are often less nimble than their smaller counterparts and time can expose any flaws that a company this big can have.

This is not to say that Bitmain will simply give up their large share of this very lucrative industry, but there is certainly a lot of room for competition. If you believe in the free market as I do, it’s easy to see that any imbalance will even out over the long term. Right now there’s a manufacturing imbalance. Mining manufacturing centralization is a short term problem.

Conclusion

Miner centralization has been a boogie man for people in the Bitcoin community for a long time. What’s worse, a lot of people continue to believe that a majority can “control the network”. The emergent properties of decentralization help quite a bit here and Bitcoin is much better protected against such centralized control than many believe.

Furthermore, mining centralization is not structured in such a way as to last too long. Mining is a commodity game and those tend to lower in price as time goes along. Obviously, Bitmain will try very hard to protect the market share they have, but such attempts without producing the best product tend to be expensive and short-lived.

Mining is not a single point of failure and Bitcoin will survive.