Meditations on Fraud Proofs

Meditations on Fraud Proofs

By Paul Sztorc

Posted April 14, 2018

Toward a coveted O(log(n)) blockchain validation, for (?) ~ $50 a month. Plus: compensation for full nodes. Fraud proofs are a very complex, nasty business.

But if you would to learn my thoughts, sit here by the river and we may meditate together.

( River art by Benihime Morgan)

( River art by Benihime Morgan)

tl;dr

- Fraud Proofs allow “SPV nodes” to have similar security to “full nodes”. SPV nodes are very easy to run and scale much better.

- Here, I require an “SPV+ mode”. Whereas regular SPV requires headers only (~4 MB per year), this mode also requires the first and last txn of each block (~115 MB per year).

- “SPV+ nodes” must have a payment channel open with a full node, or a LN-connection to a full node.

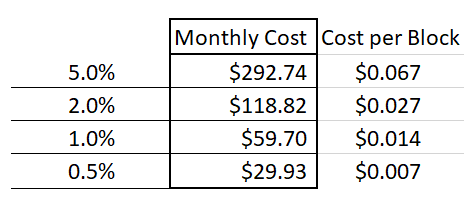

- “SPV+ nodes” will have to make micropayments to these full nodes. To validate every single block, I estimate these payments to total ~ $50 a month.

- From there, it is just a few new OP Codes, one [off chain] rangeproof, and a second “SegWit”-like witness-commitment trick.

1. Background

A. Making Bitcoin More Like Physical Gold

Bitcoin is designed to rival gold. And in many ways, BTC is far superior, but one deficiency is when it comes to receiving money– how do you know you’ve been paid? With physical gold it is straightforward – as simple as any other hand-held exchange. But with Bitcoin (a digital collectible) your guarantee of ownership is much more abstract.

Satoshi’s solution was a fancy piece of software, “Bitcoin”, that tells you when you’ve received money.

But this is an infinite regress! What is the software doing?

Well, the software has a unique way of synchronizing with other instances. Kind of like Dropbox, but where your files would never have version control issues. It asserts its own synchronicity. “Knowing you have been paid” and “knowing you are synchronized” are the same thing!

Satoshi’s whitepaper advocates two different ways of ‘knowing you have been paid’:

- [Positive, Traditional] Run the software and wait until you are fully synchronized.

- [Negative, Experimental] First, run a ‘lite client’ which would strategically synchronize some “easy parts” only. And then be on the lookout for ‘alerts’.

The first is the so-called “full node”, and it relies on positive proof– you are shown X, and when you see the X you known that you’ve been paid. The second is the so-called “SPV Mode”1 and it additionally relies on negative proof– you are not shown Y, but if you were to see a Y, you would know that you have NOT been paid. This Y is called an “alert” in the whitepaper, but today it is known as a “fraud proof”.

B. Theoretical Support for Alerts

To me, the most interesting aspect of the negative proof method (ie, ‘alerts’) is that it resembles the way our world actually works in most respects.

Consider these examples:

- We don’t try to always make murders 100% impossible. But, if someone experiences a murder, we go to great lengths to catch the murderer (and establish their guilt in court, and punish him/her).

- We don’t try to make “bad businessmen” 100% impossible. But, if there are incompetent businessmen, we expect that they will eventually go out of business or be bought out, and thus replaced with someone more appropriate. If there is too much of a conflict of interest, we use tort law or regulation (to get rid of what we don’t want).

- We don’t [even] publish scientific research as though it were 100% error-free. Instead, we make it maximally open to later criticism and future correction.

- We don’t try to prevent judicial corruption 100%. But we do require all legal proceedings to be written down, and be audit-able by the public and by future legal scholars.

- We don’t try to “know everything”. But we expect to be able to “look it up” in a book/website, and we expect that specialists will correct those references over time.

In general, we have a kind of standing assumption that everything is satisfactory. And when severe-enough errors pop up, we act to correct them.

But, otherwise, in the real world, we find it far too difficult to 100% validate every single thing.

C. Theoretical Problems with Alerts

The problem with alerts is that Satoshi never actually implemented them, as you can see from this tweet from Eric Lombrozo last month.

Here are some of the outstanding puzzles:

- DoS Resistance: Bitcoin full nodes are robust to DoS thanks to huge asymmetries in proof of work – namely, that it takes ~10 minutes to make a block but far less than 10 min to validate one. However, is this the case for alerts? Do they have PoW? Who pays for it? If not, what prevents a malicious agent from spamming innumerable false alerts at all times, making any true alerts un-discoverable?

- Proving a Negative: a malicious/negligent miner can just discard parts of the block. But, even more extreme, a miner can actually mine a block without knowing anything about what is inside of it! If these “unknown” parts of the block contain bad txns, how can we ever learn about it? If no one can learn of them, how can we warn others?

The first problem asks us to find a spam-resistant signal that is not the blockchain itself – we will solve it using Payment Channels.

The second problem asks us to draw our [very scarce] “auditing attention” to specific parts of the block – we will do this by allowing people to claim that they do, in fact, know the entire block (all sections included), and by allowing those people to back up this claim with an audit.

2. The Problem

A. SPV Mode

Satoshi’s SPV Mode (whitepaper section 8) observes that:

- Bitcoin block headers are very small (4 MB per year) and easy to validate, regardless of how many txns each block contains.

- It is very easy to demonstrate that a block contains some item “X” (as this requires only “X” itself, the block’s header, and a valid Merkle Branch containing both).

For those who are unaware, consider this example:

Imagine that we have three Bitcoin headers: headerA, headerB, headerC.

Each header contains a hashMerkleRoot: hA, hB, hC, respectfully.

Is [Tx] in any of these blocks? [header A] , [header B]

Yes, because h( [tx] ) = ht , and

h( ht, hs1 ) = hi1

h( hi1, hs2 ) = hi2

h( hi2, hs3 ) = hA

ht is the hash of the transaction [Tx].

hs1, hs2, hs3 are the Supplied Hashes, given by the Full Node ("Fred").

hi1, hi2 are intermediate hashes, calculated by SPV user ("Sally").

In practice, no one can link hA to anything other than h(hi2, hs3). In turn, no one can link hi2 to anything other than h( hi1, hs2 ), ..., and no one can link ht to anything other than [tx].

The Merkle Branch (the “supplied headers”, as well as information about their order and position) is small and grows at the coveted log(n) rate. The payer can easily obtain/produce it, and they can easily send it to you while they are sending the transaction itself. So it is quite negligible.

Which means that this demonstration suggests that, in order to “know you’ve been paid”, only the Bitcoin headers are needed. And the headers are very easy to obtain.

So SPV mode seems to suggest unlimited throughput, at tremendous ease.

B. The Problem with SPV Mode

The catch, is that you can never be sure if a given 80-byte header really IS “a Bitcoin header” or not.

The only way you can know that, is if you examine its contents in full. If a single invalid or double-spent transaction is hiding in there somewhere, the block will be invalid (or if the block is “flawed” in any other way, see “Block Flaws” below).

C. The Good News

While one cannot know if an 80-byte header is a Bitcoin header, we fortunately can validate the proof-of-work on a header. By simply hashing the header we can check it against the current difficulty requirement.

(And headers are so kind as to themselves contain a critical pair of information: the difficulty requirement itself, as well as the timestamp information – each can be used to check the other).

So, we can check that hashing effort has been expended, but not that the hashing was done on a worthy target. If you were buying a box of chocolates as a gift, and you had Matthew the Miner go to the store and purchase them for you, then our situation would resemble one where you could easily verify that Matt spent $300+ on the chocolates, but you can’t know if the chocolates in question taste any good or even if they contain any actual chocolate.

D. Positive and Negative Proof, Revisited

You could eat all of the chocolate yourself, which would give you “positive proof” that each and every chocolate was delicious.

Or else you might rely on “negative proof”, perhaps by reasoning as follows: “This box of chocolates is tamper-resistant, and it does not seem to be tampered with. And this product have a brand associate with it, and my country enforces laws protecting brands/trademarks. This brand is purchased by many, and so, if the chocolates were of unreliable quality, I would probably find a news story (or bad Yelp reviews, etc) if I looked. In fact, I have looked for such a story but haven’t found one.”

Another example is a money back guarantee. Imagine you are shopping for a car (an item of uncertain quality, just like our newly-found but unexamined Bitcoin block), and three competitors (call them “A”, “B”, and “C”) each offer to sell one to you. Perhaps you are most interested in Car C.

Positive proof would be driving Car C for thousands of miles and having various mechanics check each piece of the car, and report back to you with problems.

Negative proof would be to observe that Competitors A and B each offer a legally-binding money back guarantee if their cars break down in the next 40,000 miles; but Competitor C does not make such a guarantee. This is negative proof that C is of low quality.

For Bitcoin Fraud Proofs, we need something that always shows up if the block is valid, but never shows up if it is invalid. (Or vice-versa.)

In game theory this is called a “separating equilibrium” in a “signaling game” (or more precisely a “screening game”), where the fraud-proof-senders are of two types, “Honest”-type and “Dishonest”-type, and we are trying to cheaply screen them for dishonesty.

E. Our Requirements

We need a way to promote “block flaws” in our attention. And ideally it must do so quickily (ie, “before transactions settle” ie “before 6 confirmations”, or [to be safe] within 20 or 30 minutes).

Specifically, the following must happen:

- “Sally” (SPV node) gets paid, in BTC, for something. Her counterparty shows her his txn, and she can see that her txn appears valid.

- Sally wants to know that her txn has 6 confirmations, without running a full node. So she first downloads all Bitcoin headers, and second asks for a Merkle Branch that contains both [1] her txn and [2] a recent header. She gets one, but unfortunately for her [and little does she know]: the header is invalid for some reason. …

- Simultaneously, “Fred” (Full node) must become aware that something is amiss. Specifically: that a block contains one or more “flaws” (see below).

- Fred must have an incentive to provide some kind of warning (ie, the “alert”).

- In all other cases, Fred must have a disincentive to provide these warnings (ie, no “false warnings” … no warnings when there is actually nothing to worry about).

F. Classes of Block Flaw

A block can be flawed in many ways (see validation.ccp, especially “CheckBlock”). I have arranged them into four classes:

- “Class I” – Bad Txn (invalid txn, doublespent txn, or repeat txn).

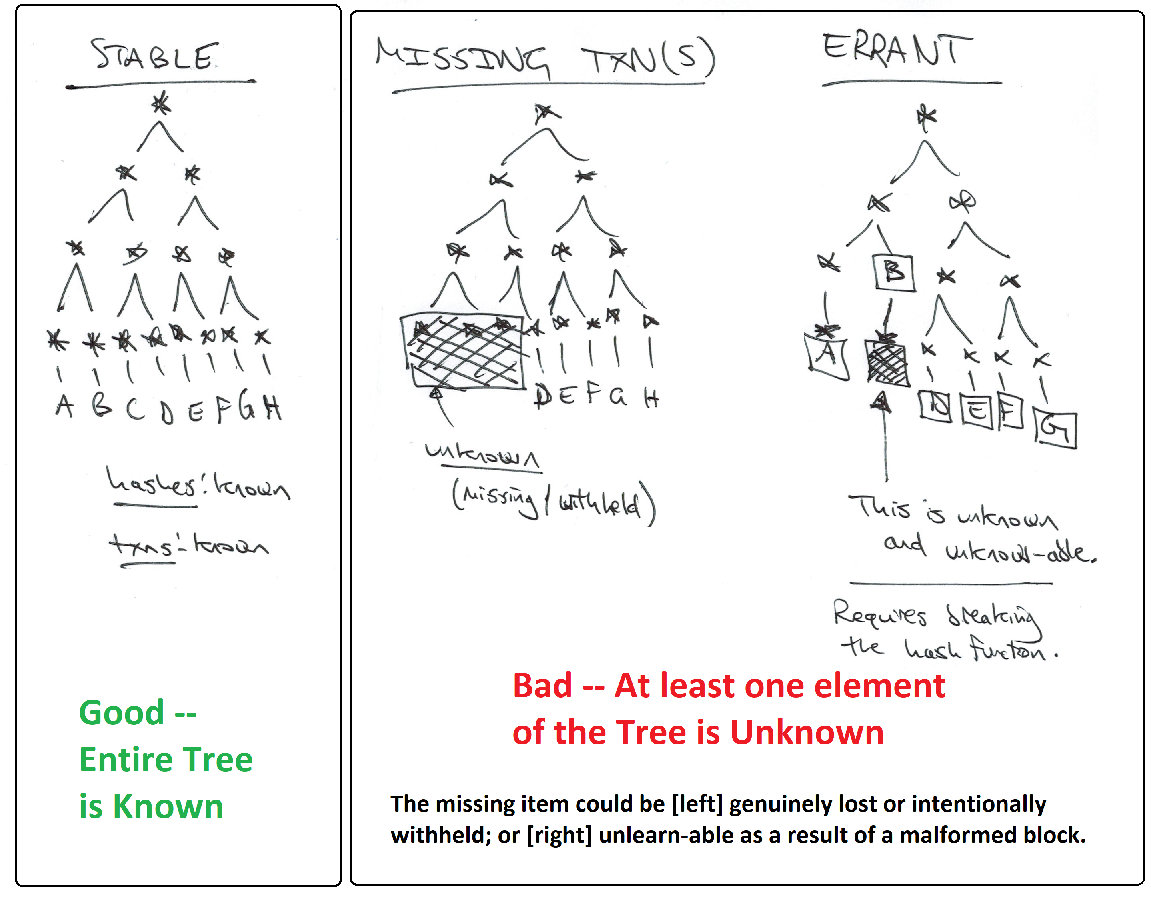

- “Class II” – Missing block data (the Merkle Tree “neighbors” of Sally’s txn are unknown and undiscoverable – this could be intentional or accidental).

- “Class III” – Bad Block (Other) (misplaced coinbase, wrong version, witness data missing, [drivechain] most updates to Escrow_DB/Withdrawal_DB)

- “Class IV” – Bad Accumulation (the infamous blocksize/SigOps limits, the coinbase txn fees [which must balance total fees paid by the block’s txns], [drivechain] sidechain outputs – the “CTIP” field of “Escrow DB”)

Class I

The first class is very straightforward. Sally can verify that a txn is invalid by simply trying to validate it and reversing the outcome (so that “false” validation returns “true”), more details below. In SPV mode, even nLockTime and CSV items can be checked, because Sally will have the Merkle Branch and all block headers. A doublespent txn can be checked even more easily, by just examining two txns and observing that they share an input. A repeat txn would fail the same test, as it necessarily would be a double-spending txn (unless it were a coinbase txn – see Class III Flaws).

Class II

The second class is of particular relevance to SPV users, because they must assume that the rest of the block exists, while [by definition] being prohibited from examining any of it. To make matters worse, miners can (and do) generate new blocks without checking the block contents. So it is possible the new blocks will have content that no one knows. Thus the assumption seems unjustifiable.

I will show that, conditional on a valid “header + Merkle Branch” being shown to Sally, a “full Merkle Tree” [ie, one containing Sally’s txn, as well as a known finite number of other valid Bitcoin txns] exists in theory, even if not in practice. Therefore, all flaws involving missing blockchain data (all “Class II” block flaws) are “problems of a missing Merkle Tree neighbor”. Therefore, they are problems of an unknown hash preimage (much more tractable). More specifically, they are problems of sampling unknown hash preimages.

My solution to this problem will require Sally to obtain the last transaction (plus Merkle Branch) of each block2.

Class III

The third class is quite general, but I believe that each trip-up can be solved with a simple trick that is specific to it. For example, the block “version” can be obtained from the header, which is already SPV-mandatory.

Most other information can be obtained from coinbase txns, so SPV users might be required to have all coinbase txns (in addition to all headers). From these, they can learn: that the coinbase appears only once and in the correct spot; that the witness commitment exists, and what it is; and that all of Withdrawal_DB is correct, as is most of Escrow_DB.

For one section of drivechain’s Escrow_DB, mainchain3 SPV nodes must become aware of the cumulative effect of the block’s inter-chain txns. This will be handled as a Class IV flaw (section 7).

So we need to add some overhead – making a kind of “SPV Plus” mode (or “Surround SPV”). Instead of merely needing Bitcoin headers (80 bytes per 10 minutes), “SPV+ nodes” also need the first and last txn of each block, and a Merkle Branch for each.

- Old [Satoshi’s Classical SPV]: 80 bytes, per block in the blockchain ; + one (txn, Merkle Branch) combo per txn received.

- New [This “SPV Plus”]: 80 bytes + (coinbase txn + last txn) + two [non-overlapping] Merkle Branches, per block in the blockchain ; + one (txn, Merkle Branch) combo per txn received ; + channels open with a few Nodes.

How many extra bytes? Well, we can’t know for sure, but if coinbase txns average 1000 bytes, and ‘last txns’ average 280 bytes, and each block contains about 5000 txns, then the overhead would rise to 2192 bytes per block4, instead of a mere 80. And the overhead grows at O(log(n)) instead of O(1).

At 52,596 blocks per year, the annual overhead would be ~ 115 MB instead of ~4 MB. This is a big relative increase, but small absolute one. Furthermore, Sally only needs to download this extra data for the blocks which she wants to fully check for validity: this could be the last 6 months of blocks, or all of the blocks in which she receives BTC (and the ~10 blocks surrounding it), and/or perhaps some random audits strewn here and there.

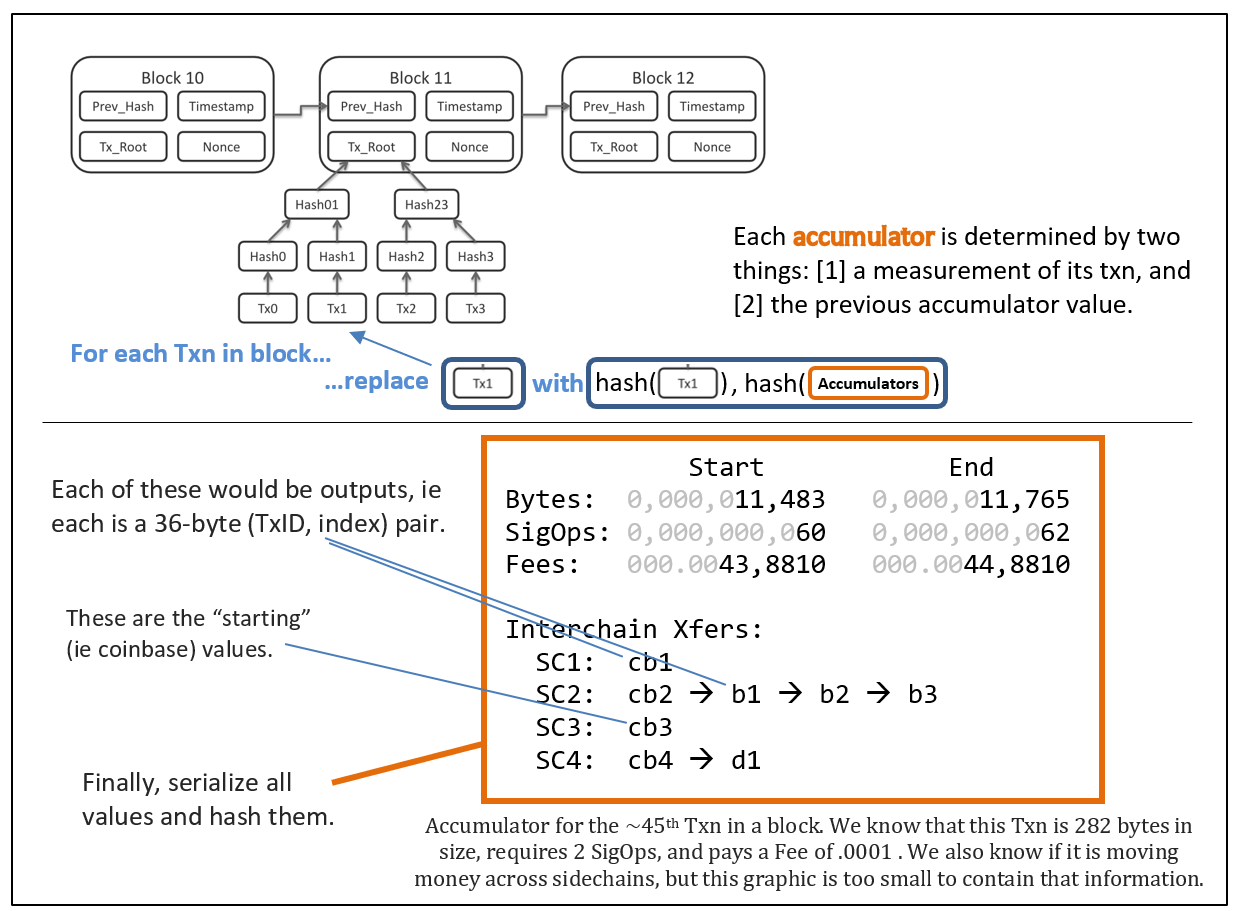

Class IV

The fourth class is especially interesting. In Section 7, I will describe how we may turn Class IV flaws into Class I flaws. In short, I will force each transaction hash to commit not only to itself, but also to its contribution to all cumulative metrics. For example, a txn will not only commit to “being 277 bytes” but it will also commit to “increasing the size of its host block from exactly 500,809 bytes to 501,086 bytes”. Then, any problematic “liar txns” can be singled out and identified. It also means that the last txn will reveal valuable information (the total number of txns, the total size of the block, total txn fees paid, etc).

But before I give more technical details, I am worried about losing people in the weeds. So I will now present the “big picture”, in the form of a story.

3. A Story

This story will star “Fred”, a full node; and “Sally”, an SPV node.

For simplicity, the story focuses on Class I and II flaws. ( Class III flaws should be checked by downloading additional data, see above, and Class IV flaws will be recast as Class I in section 7. )

I

- Fred: “Here’s that transaction you wanted. Wow, it says ‘300 BTC to Sally’. Is that you?”

- Sally: “Yes. I’m selling a SpaceShip to Peter Thiel so he can visit Jupiter.””

- Fred: “Cool, that sounds normal. Ok here is your Merkle Branch and here are all of the recent headers.”

- Sally: “Yes, I can easily check the Merkle Branch by taking a few hashes, and it is also easy for me to check that the headers all meet the difficulty requirement. Wow. Praise Satoshi.”

- F: “Praise Satoshi.”

- S: “But how do I know this header is valid? Maybe the miners are misbehaving, or slacking off? Peter Todd told me that SPV sucks and stuff.”

- F: “Ah, well you may be interested in some of my new services.”

- S: “Oh? What are they?”

II

- F: “The first is called ‘Invalidity Insurance’, and you pay me $ 0.007 , but if you later find that an invalid [or double-spent] txn was included in this block [identified by hashMerkleRoot], you submit proof of this to the real blockchain, and I will owe you $1000 over there.”

- S: “And any flaw will do?”

- F: “Yes, any type of evidence that the block is invalid.”

- S: “Wow, you wouldn’t do that unless you were certain that it wouldn’t happen.”

- F: “Yes, my computer has checked this block, and all of its txns, for invalidity. They are all valid.”

- S: “Interesting.”

- F: “But if you haven’t found any flaws in 12 hours [72 blocks], the insurance expires.”

- S: “I see. But this block should have fully propagated to the entire network of full nodes within 10 minutes.”

- F: “Yes, and 12 hours is longer than 10 minutes by a factor of 72.”

- S: “Well, as long as there is an incentive for fraud-laden information to propagate, it should definitely become available to the public within 12 hours.”

- F: “Yes, incentives are the crucial thing.”

III

- S: “Wait, maybe part of the block is missing. Sometimes, I’ve heard, miners will mine on a block without even knowing what’s inside it! What happens if they never learn? How will we know what’s there!?”

- F: “Well, I actually do have the entire block, its all here.”

- S: “Really?”

- F: “I definitely do.”

- S: “Can you prove it?”

- F: “Yes. In fact it is my second new service offering.”

- S: “Cool.”

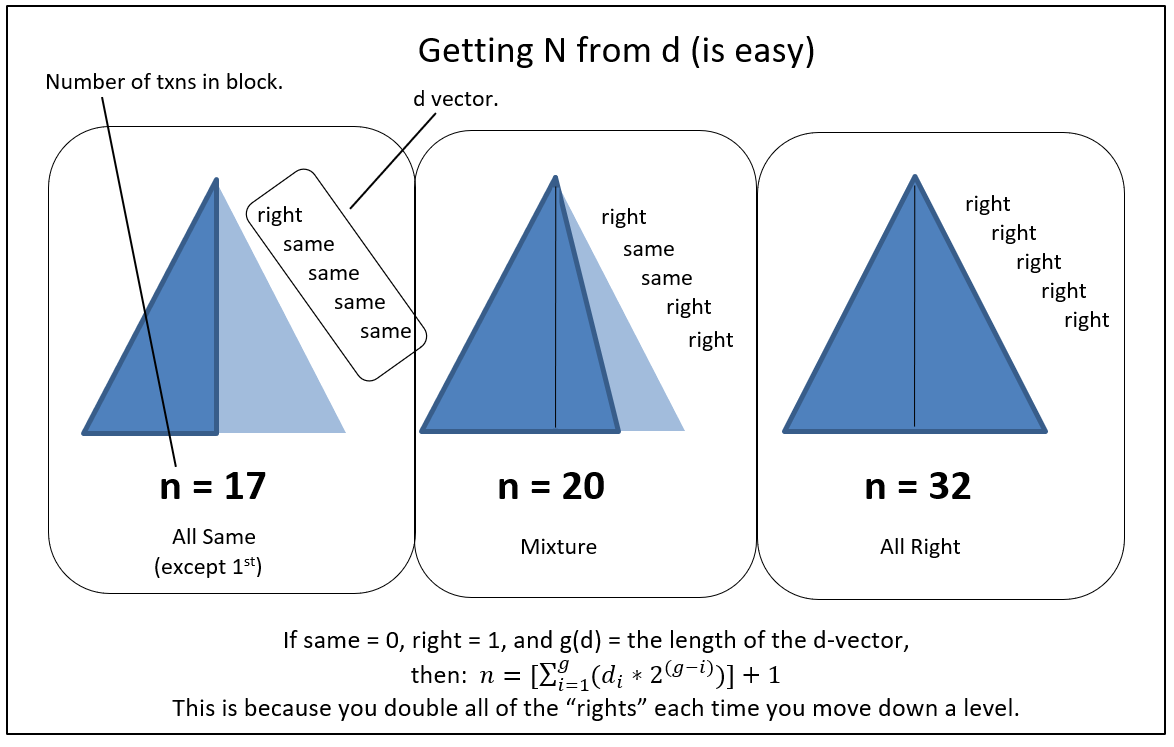

- F: “First: here’s the last txn in this block. You can tell because we only went ‘right’ down the Merkle Tree, never left; or else we hashed something twice (which indicates that this level had an odd number of items). And you can compare this Merkle Branch to the one I just gave you for your transaction. They have the same root.”

- S: “Yes, you seem to have indeed given me last transaction, of the Merkle Tree that my txn is in.”

IV

- F: “The tree is eleven items deep, so you know that there are at most 2^11 = 2048 txns in this block. And you know how many times you hashed something with itself, and when, so you know what the Tree looks like. In particular, you know the exact length of its base.”

- S: “Wow, I guess I knew more than I thought! Do I really know all of that?”

- F: “Yes.”

- F: “All items need to be the same depth into the Merkle Tree. Or else there will be a mismatch – a situation where one is taxed with finding X that, when hashed twice, produces a value that is equal to hashing “a real txn” once. In other words, an ‘uneven Merkle tree’ would require its maker to find X such that h(h(X)) = h(transaction). But this is a ‘hash collision’ (considered impossible) – such an X cannot be found.”

Fun fact: something cannot be both a Sha256 hash and also be a valid Bitcoin txn. For starters, the minimum Bitcoin txn size is 60 bytes (too big to be a 32-byte hash).

- S: “I think I understand – a Merkle Tree is geometrically similar to an Isosceles Triangle when there are no duplicates, and it approaches a Right Triangle when the last transaction is duplicated many times. The depth of the final transaction is depth of the triangle itself. And because of the Repeat Rule, if I just know the right edge, I know how many of the base elements (elements at the base of the triangle) are duplicates.”

- F: “You do indeed! This block, the one with your 300 BTC txn, has a Merkle Tree that is eleven units deep – ie a triangle that is 11 units tall. And, from the final txn (I just sent you), you know that you only double-hashed once, and only at the very end. So you know that this Merkle tree contains exactly 2047 elements.”

- S: “Ah, very clever… And if, instead, the depth were ten units, and all were self-hashed (except the first of course), I would know that there were only 513 unique final elements.”

- F: “Exactly.”

- S: “Wow.”

- F: “And what if I gave you a new tree, and a new “last txn” with a Merkle path: [A, (self), B, C, (self)] ?”

- S: “It is five units deep, and has 23 unique elements in its base.”

- F:“Precisely correct.”

- S: “I’ve learned so much!”

- F: “Now, one last thing: each of these final elements is either known or unknown. And, if known, it must either be a valid txn or NOT be one. So each final element must either be: [1] a valid txn, [2] an invalid txn, or [3] a piece of information that no one can discover.”

- S: “That seems straightforward.”

V

- F: “Great. So, you can see that your block contains L=2047 txns.”

- S: “It seems to.”

- F: “Now here is my second service…I charge even less, just $ 0.0001 for this one! You pick a bunch5 of integers5 randomly, between 1 and L, and I’ll give you their txns and paths. If I can’t do as promised, I’ll give you a boatload of money.”

- S: “You seem really confident that you can do it.”

- F: “I sure can! You can coordinate with your friends to pick the specific txns that you think I’m missing. I promise I’ve got them all!”

- S: “Wow, cool. I’ll take it.”

- F: “One thing, though. If we sign our deal and you don’t reveal your integers6, it will look like I can’t meet the challenge. I mean, I totally can, but I don’t know which txns to reveal because you didn’t tell me. So if you don’t hand them over in a timely fashion, I will need to be reimbursed in full, and then some.”

- S: “Eh, OK I guess. I guess for my 300 BTC txn, I really shouldn’t be stingy about locking up a much smaller amount.”

- F: “You only need to lock it up for a few seconds. Believe me, I don’t want my money trapped pointlessly in this channel for any length of time either.”

- S: “Ok!”

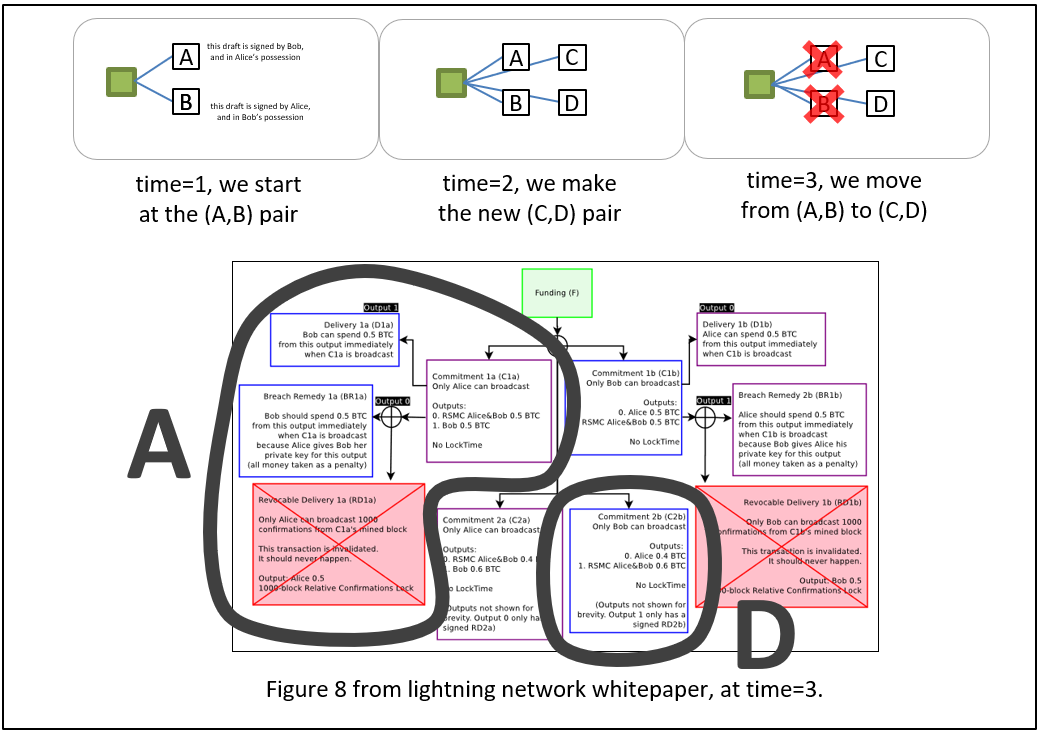

- F: “Great. In our payment channel, we are currently at pair (A,B). You will need to make pair (C,D), and then reveal the random integers after we move there.”

VI

- S: “OK. I picked some Rs [random number]s, and made C and D [the next payment channel iteration]. And I signed D for you, so here you go.”

- F: “Great thanks. Hmm…good job, this looks like you formatted everything correctly.”

- S: “And here are those Rs, the random integers I cho–”

- F: “No! No no no, not until later!”

- S: “Oh, sorry!”

- F: “That’s OK.”

- S: “But if I only show you the Hs, ie H(R) the hash commitment of R, then how will you know that I am actually following our scheme? Maybe I didn’t pick integers in range(1,L)? Maybe, instead of choosing numbers like (5, 470, 4, …), I instead picked random nonsense like (‘fish’, 0x78965, ‘_’, 987987987, …). Then, when I reveal my nonsense, you will not be able to show me the ‘fish’ txn…”

- F: “Ah…great question. There are professional cryptographers who have all kinds of ways of doing that. We will choose one and you will send me ‘Gs’ instead of Rs.”

- S: “Ok, I’ve used the Rs to make Gs, here you go.”

- F: “Ah yes, from these Gs I see that your Hs do in fact refer to integers in the range(1,L). Since I know all L txns in this block, I’m confident I can meet the challenge.”

- S: “Great, so are we moving forward?”

VII

- F: “Yes. Here is your signed C. And I’ve invalidated my B [per the rules of payment channel iteration].”

- S: “Ok…don’t you need me to invalidate my A?”

- F: “Yes, but if you don’t, I can just broadcast my D…”

- S: “What if I broadcast my A first?”

- F: “It will be as if this transaction never took place…”

- S: “Aha! But I already know that you are willing to agree to do this! So you already do know that the block is valid– “

- F: (raises his eyebrows dramatically) “Do I?”

- S: “–which means I got what I wanted and now I don’t have to pay.”

- F: “Well, you know that I’ve agreed to do the challenge, but not that I actually can do it.”

- S: “…”

- F: “And you knew, before starting this process, that I was offering to accept the challenge. So you haven’t really learned that much more. I don’t see why you would decide to back out now.”

- S: “…”

- F: “Maybe I knew you’d try to back out. And so I offered to sell you an Audit, but really I don’t know anything about the block’s validity.”

- S: “…”

- F: “ You know, one one-hundredth of a cent really is quite small, compared to the cost of a whole Spaceship.”

- S: “Fine…I’ll invalidate my A. Here you go.”

VIII

- F: “Ok, now you need to reveal your Rs”

- S: “Great. They were 453, 531, 14, and 2011.”

- F: “Oooh good ones! .. Ok here are txns #453, #531, #14, and #2011; and here are their Merkle Branches. You can see that I had them all.”

- S: “Wow, great. This is so cool. I love Fraud Proofs.”

And finally, before I explain Invalidity Insurance and Fullness Audits, I offer a review of Payment Channels and the Lightning Network.

4. Payment Channels – An Overview

A. Regular (Non-Channel) Payments

With regular (non-channel) payments, the money is transfered when a “message” containing it is included in the blockchain.

It is as if Friend A emails you saying that you now have 4 of their 12 BTC. And then you click ‘reply all’ and say that Friend Q now owns 2.7 of that 4 BTC. If ‘the blockchain’ contains a copy of these “emails”, then the txns are said to have happened.

B. Payment Channels

In payment channels, two people first “fund” (or “create” or “open”) a channel. They do this by activating some of their BTC – taking it and paying it back to themselves. I take 90 of my BTC and pay it back, while you also take 15 of your BTC and pay it to yourself. We do this together in one txn, and it is broadcast and included just like a regular txn.

After the channel has been opened, however, the parties do things differently.

While before we actually sent “emails”, with channels we instead keep multiple “drafts [of emails]”, that we do not send. In fact, there will always be two parallel versions of the same draft – I will keep the version which is more convenient for you, and you will keep the version which is more convenient for me. The draft in my possession has not been signed by me, but it has been signed by you. The draft in your possession has not been signed by you, but it has been signed by me.

C. Updating the Channel

You and I will update these drafts together, by cycling the parallel pair of drafts through alternating states, that I call “potential” and “kinetic”.

Channels mostly remain at rest, unchanging, in the Potential state. But occasionally users will want to alter the channel, and when they do this they will move the channel to a Kinetic state, and then quickly return it to a new Potential state.

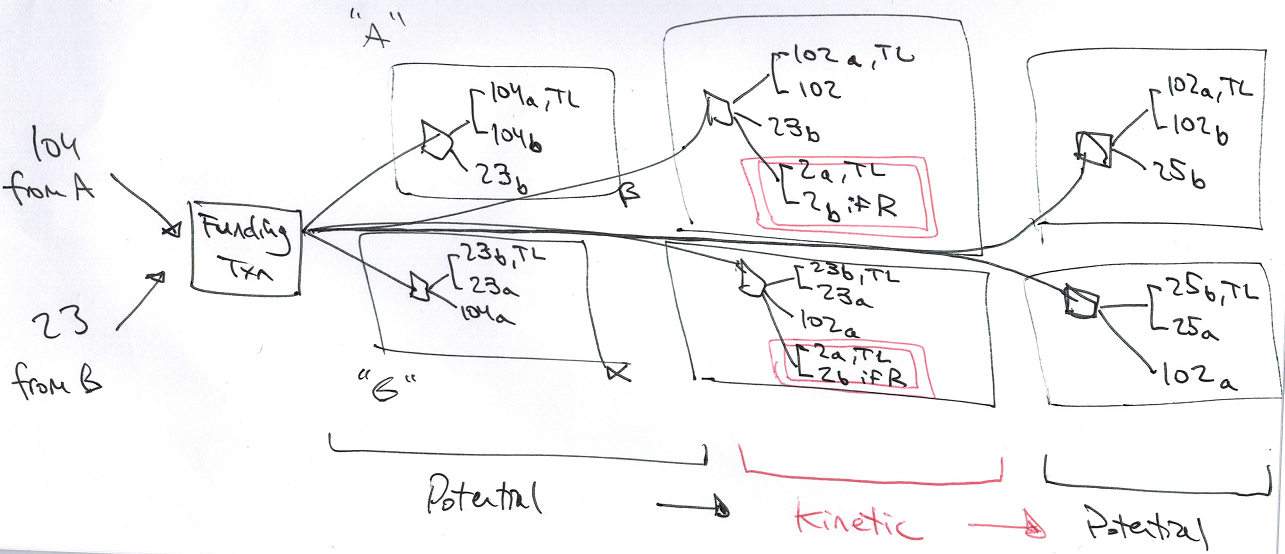

Above: The state is “kinetic” – the 2 BTC amount (pink, double-boxed) is up for grabs, but [in practice] only very temporarily. The channel will spend most of its time in “potential” states, which reflect the most recent BTC balances.

As I said above, regular transactions are said to have happened, if ‘the blockchain’ contains a copy of your “email”.

But payment channels are very different – the txn is said to have happened, if we have jointly “moved” from one pair of drafts to a new one. And this moving process is itself quite different – it does not occur when we jointly build, sign, and exchange the new pair; we must take an additional step of building, signing, and exchanging a pair of messages that torpedoes the old pair. Only then is the payment said to have “happened”.

D. Hash-Locked Contracts / “Lightning Network”

The commonly-discussed kinetic state is called a “hash locked contract”. When part of the kinetic state is shared by an interconnected line of channels (ie, a “circuit” of people), it can be interpreted as “the Lightning Network” which is explained as follows:

- A “customer” wants to pay 10 BTC to a “merchant”.

- The customer makes a secret random number “R”, and a public version of R called “H”. “H” is simply the hash of R (or “h(R)”).

- Customer finds a “line” of connected people between himself and the merchant. Customer gives H to everyone in this line7.

- Customer offers a kinetic update to “Friend_1”, the the person standing next to him in line. Specifically, customer will pay Friend_1 10.0004 BTC if Friend_1 can guess the R.

- Friend_1 knows that he cannot guess the R, but he knows that it will soon be revealed, and has nothing to lose, so he greedily accepts. The [Customer, Friend_1] channel moves from “potential” to “kinetic”.

- “Friend_1” repeats the process with “Friend_2”, who is one step closer down the line from “Customer” to “Merchant”. Friend_1 will pay Friend_2 10.0003 BTC if Friend_2 can guess R.

- The process repeats, with Friend_3 getting 10.0002 for R, Friend_4 getting 10.0001, and Merchant finally getting 10.0000 from Friend_4 if Merchant can guess R.

- With the circuit now complete, Customer passes R to Merchant, who could now use R to claim 10 BTC from Friend_4.

- Merchant releases good to customer.

- Merchant and Friend_4 do not want to pay a mining fee, nor do they want to wait for txn confirmations. So instead, Merchant waves the R in front of Friend_4, and uses it to negotiate a new channel state. It has moved from kinetic back to potential, but in this new potential state Merchant is 10 BTC richer and Friend_4 is 10 BTC poorer.

- Step #10 is repeated for the other pairs: [Friend_4, Friend_3], [Friend_3, Friend_2], [Friend_2, Friend_1], and [Friend_1, customer].

E. Flexibility

The cool thing is that kinetic txns are not limited to HTLCs (ie, “pay if R is revealed”). A LN-txn can do anything that the blockchain beneath it can do.

We will first get the blockchain to do two new things: “invalidity insurance” and “fullness audits”. After the underlying blockchain can support these “smart contracts”, we can use them in channels.

F. How Channels Help

Channels are useful for fraud proofs, because they:

- Operate meaningfully at near-instant speeds, and so have a chance of “pumping enough info” during our critical 20-30 minutes.

- Facilitate micro-transactions (payments of very very small amounts).

- Are robust to temporary mining failures (as they use long “custodial periods”).

- Can prove negatives, by: [1] asking for something, [2] offering a tiny reward for it, and [3] giving the counterparty a long time to provide it. If they don’t meet the challenge, it is very likely that it is because they can’t.

Now I can explain “invalidity insurance” and “fullness audits”.

( River art by Max Pixel)

( River art by Max Pixel)

5. Invalidity Insurance

The first solution is the simpler of the two.

( Well, I’ll let you be the judge of that, I guess. )

A. Overview

It is a payment (ie, a Bitcoin script) which is only valid if a given block (defined by its hashMerkleRoot)8 can be proven to contain a Class I Flaw.

The recipient would supply four items:

- hashMerkleRoot itself (abbreviated “hMR”).

- A Bad Txn – The TxID of a txn that is invalid for some reason.

- A Merkle branch (as described here, consisting of: branch_length, branch_hashes, and branch_directions) containing both.

- Evidence that the txn is bad.

B. Types of Evidence

The fourth item (the “evidence”) would vary based on the type of Class I flaw – (a) invalid txn, (b) doublespent txn, (c) repeat txn; and Class IV flaws, (d) ‘bad accumulator’ (see section 7).

Aside: Fraud Proofs vs Smart Contract Fraud Proofs

Before I continue, I’d like to contrast “a fraud proof existing” with “a fraud proof that can be used in a Bitcoin txn”.

I am aiming for the latter, because it is really a double-win: first, it gets us the fraud proofs themselves; and second, it gets us an incentive-compatible way of cheaply buying these fraud proofs from full nodes.

In fact, I really need the double-win, because I need to solve not only the problem of “how to make fraud proofs”, but also the free-rider problem of “ensuring that they are supplied”.

The benefit of making Bitcoin itself understand its own fraud proofs is that we can put them in transactions, and use them in Bitcoin smart contracts. But this is very difficult to accomplish. I don’t pretend to have the best answers, at all9.

(a) Invalid Txns

At first glance, one would think that we would only need to run a txn through the protocol’s tx-validation function, to ensure that it fails10. And so our “evidence” would just be the txn itself.

But I’m afraid it isn’t that simple. There is a hangup!

Each Bitcoin Merkle tree contains supposedly-valid transactions, as we know. But (!) it also contains its own interior nodes! What do we do if Sally tries to claim that a “transaction” is invalid, and then shows us a Merkle path to “two 32-byte SHA256 hashes strung together”? How do we know that these bytes represent an invalid Bitcoin txn, when instead Sally may have stopped halfway along the Branch? She may be lying about the depth of the Merkle tree!

And what of the reverse case (if Evil Fred deliberately constructs an invalid transaction, such that it takes the form of 64 random bytes)? Who’s scamming who?!

To address this hangup, we require Sally to also provide a Merkle Branch to some other transaction that is valid. For maximum convenience, this might be her own transaction (the one she was given when she received money, at the very beginning of this process), or else it could be the coinbase txn (which she always has in “SPV+ mode”).

Thus, in this scheme, proving that a txn is invalid actually requires two transactions total – the bad txn itself, and some “evidence” in the form of a good transaction nearby with an equal-length Merkle Branch. And so (a) is actually quite similar to (b) and (c) [the next section].

(b, c) Double-spends and Duplicates

For (b) and (c), the evidence of fraud my also initially seem straightforward. We just need two txns, and two Branches – then we see that the txns share an input (or a hash).

But I’m afraid there is a hangup for this one as well. It is the location of the second txn (by “second” I mean the chronologically “first” txn, aka the “real” output that someone is trying to illegally double-spend). This txn might be in a different block.

In fact, it might be several hundred thousand blocks away.

If the script interpreter can access past headers, then we may be able to do our work, with just a single additional 32-byte hash. I don’t know the best way to do this – perhaps a new OP Code which is designed to fail if the next 32 bytes are NOT part of a known set of past hashMerkleRoots.

At worst, it would mean something rather cumbersome – appending an entire sequence of headers, from the header that we have backwards to the header of the block that contained the “real” spend of this output. From there, of course, it is a simple matter of including a second trio of [header, Merkle Branch, and txn], indicating a valid txn that already spent this output. (Or, for (c), a valid txn that has the same hash.)

Horribly, if the double-spend is of a coin spent many years earlier, we will need hundreds of thousands of 80-byte block headers just to get to it. This chain of headers could itself be 16 MB in size (!), making this transaction too large to ever include. Obviously, an area for improvement. In fact: a few people, including Blockstream, have published work (see Appendix B) on shrinking down one million 80-byte headers into something that is merely “tens of kilobytes” or so.

If you know the best way to handle this, leave a comment below!

(d) Bad Accumulator

For (d), Bitcoin needs a way to understand the data in txn’s “accumulator” (or “second witness”). And it needs to check this data against the txns properties. Details to follow in section 7.

( And, again: very easy for software to do, but much harder to get it into a Bitcoin script. )

C. Putting it Together

With the script built, we can now deploy it strategically, in channels, to insure against the invalidity of a given block header.

Specifically, for each header, we will send a channel into its ‘kinetic’ phase, such that:

- Sally is paying Fred a tiny amount more, unconditionally, and

- Sally may be able to extract a lot of money from Fred, if she can obtain evidence that the header in question is invalid. Else, after some amount of time (1000 blocks or whatever), the money returns to Fred.

The first is kind of like an insurance premium, and the second is like an insurance claim– money to be claimed by Sally if the conditions are met, but otherwise reclaimed by Fred if they are not.

An honest Fred has every reason to sign txns of this kind. To him, the evidence in question will never be obtained, so the claims will never be paid, and the premium payment is just free money.

Thus the “fraud proof” here is actually in reverse – when these types of txns stop being offered, we are alerted to Fraud.

However, under one condition, a dishonest Fred might still offer the service. We mentioned it in the story – it is: if the txn data is missing. A Dishonest Fred knows that, if the data is missing, Sally will never be able to use it to demonstrate Fraud. And so Fred will never be “caught” – the evidence of his guilt does not exist anywhere, so Sally can never come into possession of it.

That is why we need the Fullness Audits [next section].

6. Fullness Audits

Fullness Audits allow Fred to demonstrate [to Sally] that he actually has every transaction in a block.

A. Two Ingredients

First, we need a new “weird ingredient” for this one: something that transforms “an integer” into “Merkle path directions”, and back.

The funny thing is, though, we actually don’t need to do anything for that. The directions are already stored (for Namecoin merged mining, anyway) as a single int32_t. It even says that this value “…is equal to the index of the starting hash within the widest level of the merkle tree.” It’s just how the binary encoding of integers happens to work! So: problem solved.

Our second weird ingredient, range/set-membership proofs, is allowed to make use of off-chain interaction, as you hopefully noticed in Section 3. So we’re mostly off the hook for that one as well.

Let me add, that there is currently a whole team of Jedi-level Bitcoin cryptographers working full-steam on rangeproofs, for unrelated reasons (they want to use them on chain, to hide the transaction amounts of Bitcoin txns). Our use of them is significantly benign by comparison.

Leave a comment below if you think you have the best commitment scheme to use (see “(3) insurance claim” for details)!

B. Putting it Together

What does happen on-chain (or, more specifically, inside of a payment channel [such that these instructions might need to be pulled on chain at any time]) is:

- A small payment from Sally to Fred, regardless of anything. This is Fred’s fee, or the “insurance premium” (again: it is cheap, because it is on something Fred knows will never happen).

- A very large payment from Sally to Fred, if Sally goes many blocks without revealing her secret “R”s. This payment must be larger than the insurance claim (below), to ensure that Sally does her part on time. It is a kind of fidelity bond.

- A large payment from Fred to Sally, the insurance claim, if Fred cannot provide the part of the block that Sally requests.

(1) Insurance Premium

The first [“insurance premium”] is quite trivial to do, and is a normal channel update.

(2) Fidelity Bond

The second [“fidelity bond”] is also pretty easy, especially in LN-style channels that emphasize “hash time locked contracts”. For example, we first move 10 BTC from Sally to Fred, holding these funds “hostage”. Second, we move 10 BTC backwards from Fred to Sally, if and only if R is revealed during a “timelock” [ie, we return the hostage iff R is revealed]. Now, Sally will pay a net 10 BTC penalty if she never reveals R.

If she does reveal it, she keeps her 10 BTC, but Fred will learn the R – he can now use it elsewhere in this txn or other txns. As mentioned, this must be the largest payment, and it also must be a briefer timelock, which is to say that the second timelock (below) must be twice as long as this one, to ensure that Fred has at enough time (ie, worst case Fred still has a whole “timelock unit”) to do his part after obtaining the critical R’s.

(3) Insurance Claim

The third [“insurance claim”] is a little stranger.

The insurance claim takes the form of a ‘fidelity bond’ holding Fred’s money hostage, not Sally’s. Fred can only get his money back if he provides a number of items.

I will describe these items in two sections. The first section acknowledges the original parameters of the contract:

-

Fred must supply two integers (X, R) such that commitment( c(X, R) ) matches a predefined H1, and hash(R) matches a predefined H2. These H1 and H2 values were supplied by Sally when she picked her random numbers and created the new channel-state. *

-

“X” is the Merkle tree index (see first ‘weird ingredient’, above), and “R” is a random 256-bit integer that was chosen by Sally. *

-

Sally will reveal R, in order to reclaim her “Fidelity Bond” (second payment, above). *

-

Finally, using this R, Fred can derive X (he merely needs to compute L hashes, where L is the total number of txns in the block [see above]). Therefore, he can supply it.

-

Easy enough so far. But there is still one last requirement for this first section:

- The commitment must be such that Sally can make an (off blockchain, arbitrarily large/interactive) rangeproof to Fred that X is an integer within range(1,L).

- ( So the commitment might not take the form of a hash. And so it may require script-versioning or a new OP Code or some other even more advanced technique. Or it may only involve algebra. Choosing the best way is not my area of expertise, sorry! Ask Andrew Poelstra. )

The first section only acknowledges “what Fred agreed to do”. Fred has yet to actually do it!

So, in order to fulfill the contract, Fred must also:

- Interpret x1 has a Merkle tree index, and provide a Merkle Branch that has the same index and one that ultimately hashes to “H3”, the hashMerkleRoot of the header we are examining. Thus Fred shows that, whatever random number Sally picks, Fred can show her the corresponding hash.

- Finally, Fred must provide the preimage of that hash.

Basically: if Fred can show the preimage in question, he passes. Otherwise he fails.

If this preimage is a valid transaction, then everyone lives happily ever after. But if it fails validation for any reason (for example, because it is garbled nonsense), then it will allow Sally to profit tremendously by taking advantage of “Invalidity Insurance” (section 5). The two services work together.

C. Repeat Audits

Obviously, Sally’s likelihood of catching fraud on the first try is very low: 1/L probability. So, Sally should want to try again and again. And Fred should be happy to let her, because he makes a small amount of money on each audit.

D. [Optional] Converging on Missing Data

Top Down and Bottom Up

One can think of a Merkle Tree, visually, as a giant “triangle”. Typically, the triangle is solved “bottom up” – which is to say that the lowest level is built first, and the “top” level is built last. Then the top item (the Merkle root) is compared against the blockheader.

Full nodes will always “solve the triangle” this way, for two simple reasons: [1] full nodes are expected to have the entire base layer already, and [2] each layer fully defines all the layers above it.

But SPV nodes may elect to also solve the triangle “top down” by working downward from the Merkle Root. This lets them “snipe” into exact locations of the triangle, without having to do the work of storing the whole thing.

( This may also interest “full nodes” that are in the process downloading and validating a newly-found block. They will need to store (for recent blocks) “the whole triangle” – ie all of the intermediate hashes. )

The “Whole Triangle”

How large is the whole triangle? Well, here is a table:

| Depth | Items in This Layer | Cumulative Items So Far |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 2 | 3 |

| 3 | 4 | 7 |

| 4 | 8 | 15 |

| 5 | 16 | 31 |

| 6 | 32 | 63 |

We see that, if “n”, is the first column, then the second column is “2^(n-1)” and the third column is “(2^n)-1”.

So the third column [the “whole triangle”] tends to always be twice the size of the second column [the triangle’s “base”]. So, if we store the whole triangle instead of just the base, the storage requirements [for hashes] only increase by a factor of two.

And remember that full nodes are storing whole transactions, in addition to the txn-hashes. An 8 GB block, hypothetically, might consist of 32,000,000 250-byte txns. So the “triangle base” would be 32,000,000 32-byte hashes, or 1.024 GB. And, by the logic of the preceding paragraph, the “rest” of the triangle would only be ~ 1.024 GB. So instead of 9.024 GB, the storage / memory requirements for the full triangle would increase 10.048 GB.

(And, once the “whole” tree is obtained, the requirements go back down to their usual level of 9.024 GB.)

Auditing the Triangle

An ‘Honest Fred’ will have the whole triangle available to him, but a Fred that is missing part of the block will not. He will even be missing some “mid-to-upper” Tree values – these are much easier to audit because they are far fewer in number.

And in fact, Sally can easily ask for an arbitrary hash, somewhere within the triangle.

Her process for doing so is, actually, exactly the same bullet points as I have given above! The final bullet point, instead of revealing a Bitcoin transaction, would instead just reveal [hopefully] two 32-byte hashes. (Sally would not use this data to cash in on invalidity insurance, in fact the reverse – she would just use it as more evidence that Fred does indeed have the whole tree.)

7. Class IV Flaws (Bad Accumulators)

Until now, I’ve avoided talking about an entire category of Block Flaws – the “Class IV flaws”. These concern aspects of a block that span multiple transactions.

I will first explain them, and then offer a strategy for transforming them into “Class I” flaws.

A. Evidence That Spans Multiple Txns

Consider violations of the blocksize limit – the infamous rule stating that the total size of all transactions (summed together) must be beneath a certain size. If Evil Fred makes a block that is too large, for example 1.0001 MB in [non-witness] size, then how can Sally ever become aware of this?

[ Merely to keep the explanation as simple and clear as possible, I will use the pre-SegWit limits of 1 MB and 20,000. ]

None of the techniques we have discussed so far will help. Class IV Flaws can occur in a block, even if every transaction is valid (ruling out Class I methods) and available (ruling out Class II methods). And “SPV+” mode alone will do nothing to help us solve it (because having the coinbase txn does not help us).

Invalidity Insurance, in particular, only highlights individual txns as being wrong. But Class IV fraud is not “at the txn level”, it is “at the block level”.

So any rules that operate at the “block level”, such as the blocksize/SIGOPs limits, we cannot check. It is problematic enough, that one hidden txn somewhere might singlehandedly be 40 terabytes long and contain a trillion SigOps. But, much worse is the prospect of tiny txn that use zero SigOps– because of these, a “crammed block” with many txns might still be valid. Or it might not. We don’t know!

In short: we need all of the parts, so that we may properly add them!

Or do we?

B. A Valid Contributor to the Whole

Perhaps, we could analyze it in parts, if each part uniquely declared its contribution to the whole. We’d just need a way to measure a “contribution”.

Let me explain.

For the blocksize limit specifically, we would force each txn to declare the “coordinates” of the “block real estate” that it was “living on”. We would not allow any txn to take up more (or less) space than it declared; and we would not allow any two txns to take up the same declared space.

So, a transaction wouldn’t just “take up 250 bytes”; instead, we would arrange things so that the txn would “take up the 250 bytes between byte #32,880 and byte #33,130”.

A metaphor: imagine that a block’s txns are always printed out on strips of paper, and that these strips are laid end-to-end, forming one line segment. I am proposing that we [first] lay this line segment against a gigantic ruler, and [second] that we staple two blank 4-byte chunks11 to each paper strip, and [third] mark these chunks with each strip’s starting and ending coordinates, as given by the ruler.

Above, in “SPV+” mode, I assumed that SPV nodes would have access to the first and last txn of every block. If the “accumulator” starts at 0, and if each txn adds exactly as much to the size of the block as it says it adds, then the ending value of the accumulator should be exactly equal to the total size of the block. If it does not, there must be one or more specific txns which are flawed. Such txns would then have Class I flaws, and trigger “invalidity insurance” (section 5).

C. Accumulator Specifics

I will start with a hard fork accumulator, because it is easier to explain.

Hard Fork

[Reminder] Currently in Bitcoin, a txn “x” has hash “h(x)”, and these h(x) all form the base of the block’s Merkle Tree.

Instead, we might have each txn “x” be described by “y = h( h(x), h(z1, z2) )”. The second item would be an “accumulator” – for example, z1 and z2 would describe the starting and ending size-coordinates of the transaction (along the entire vector of all txns).

( More precisely, z1 and z2 would themselves lists [of multiple information], because they would need to describe, not only the byte-size of the transaction, but also its SigOps-use, txn fees paid, and any change made to drivechain’s Withdrawal_DB. )

The new information z1 and z2 does not actually need to be broadcast over the network at all, or even stored. It can be generated and validated locally using just the sequence of x’s, just as it is done today. Miners are still 100% free to arrange the txn in any order they like, at any time [before the block is found].

Anyway, this data structure (“cumulative Merkle tree”?) is helpful because it makes it very easy to demonstrate fraud. Recall that we need to submit both a “bad txn” and “evidence” that the txn is bad. We will already have “y” itself, when we describe a path to a “bad txn”. So now we just need to supply its preimage [h(x),z1,z2] and then disregard the first 32-bytes.

Soft Fork

The space of possible soft forks is very large. I’m not sure what the best soft fork for this part is. More research is needed! Leave a comment below.

But one way would be to think of the “(z1, z2)” pair as a “second witness” to its txn “x”. Just like with SegWit, we could build another Merkle Tree (a third one this time) containing these witnesses, and require that it exist and that there always be a commitment to it in the coinbase txn.

The downside is that in order to prove fraud you just need a very awkward and cumbersome txn, consisting of three Merkle Branches. First, you need a Merkle Branch to the offending txn, as always.

But second, you’d need one to the block’s coinbase txn; and then, third, you’d need to [1] pick a specific output of that coinbase txn, [2] scan that output to make sure that it is the ‘second-witness-output’, and then [3] go down another Merkle Branch from there, down to the hash of the ‘second witness’ of “x”.

And all of that would be just one part of a big channel script! What a crazy redeem script that would be!! Thank heavens for Ivy. And I guess that this txn, if broadcast on chain, would probably be at least ten times as large as a normal txn. I shudder at the thought! But I suppose “cumbersome awkward txns” has never stopped us before…

A second technique would be to require every txn to be paired with a mindless “zombie txn” – one that doesn’t actually move any money, but only exists so that we can put an OP Return in there with the commitment to the second witness. This idea is quite horrible, as it wastes ~ 80 (?) on-chain bytes for every txn, and the median txn is already near-250 bytes. So txns would be about 30% bigger! How horrible! I only provide this idea to help stimulate thought for other soft fork ideas. (Note that we can’t put the commitment in an OP Return inside its own txn, because users cannot easily know “where” their txn will be positioned in the block without interacting with a miner, which would be much too annoying.)

8. Economics

A. Computational Costs

First, as I mentioned above, Sally must run an “SPV+” node, which might be expected to use up 2192 bytes per block, instead of a 80.

B. Market-Clearing Price

How much are “invalidity insurance” and “fullness insurance” likely to cost?

i. Competitiveness

First, notice that these insurance services could be provided by anyone running a full node. Second, notice that, by definition, if a blockchain network exists at all, then there are multiple untrusted anonymous parties each running nodes. So “insurance providers” are likely to be under heavy competition, and will have to offer the service at near-marginal cost.

ii. Marginal Cost Overview

What are their marginal costs? Well, to provide the service, one needs a full node, an open payment channel, and they need to monitor it. Fortunately, many people already run full nodes, and will already monitoring their open payment channels, so those marginal costs are actually zero. Only the channels will cost anything – a small fee to open a channel (or roll over an existing one), and the working capital locked inside of the channel.

But even these costs could potentially be zero. These contracts can be deployed inside payment channels that have already been opened, so while the cost of opening a new channel is nonzero, the marginal cost of opening a channel for this specific purpose remains at zero – people can freely reuse the channels they already have open. Anyone who manage their LN-connections well, won’t need to open or close very many, for this purpose or for any other.

Note: Channel Convenience

Since we are discussing the opening/closing of channels, it is important to remark that this insurance can be spread “through” the LN-network – in other words, Sally and Fred do not need to have a channel directly between them. They merely need to be part of the same “Lightning Network”. So Sally can actually buy insurance from Fred, and resell it to another Sally! This minimizes the need for channel openings/closings.

Details are in this lengthy footnote12.

iii. Time and Working Capital

Fullness Audits

The Fullness Audits need only last a brief instant of time. The required steps can happen very quickly: Sally and Fred meet, negotiate terms, create new channel states [kinetic], Fred invalidates, Sally invalidates, Sally reveals her random integer(s), Fred reveals the txns associated with it, and they jointly move to a new [potential] channel state.

Since it has almost no marginal cost, there is no limit to how cheap each fullness audit might cost. Each audit could cost one hundredth of a cent, and each user might do 40 or 50 audits per block, for a per block cost of half a cent.

I will frame all of the costs on a ‘per month’ basis. This makes it easier to compare the “fraud proof world” costs to the costs in “full node world”.

At 4383 blocks per month, and 50 audits per block (auditing every block), and (1/100th) cent per audit, the monthly cost of these audits comes to $21.91.

Invalidity Insurance

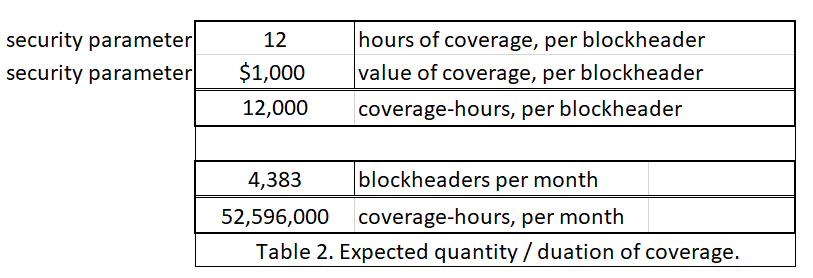

The Invalidity Insurance needs to last longer, unfortunately, because it needs to prove a negative. The question of how long it must take is a security parameter; one which asks: “If this block contained a bad transaction somewhere, how long would it take for someone to find?”.

Once a flaw has been discovered, it will spread quickly. This is because informants will quickly try to sell it.

These sales are easily facilitated, by taking the logic of the Invalidity/Fullness contracts and reversing a part of it. A new ‘smart contract’ transaction will be of the form: “You pay me $0.03 now, and in return I will either give you a flat $1000, or I will give you a block flaw for this block header”13. Since “Indiana the Informant” knows that he has a real block flaw, he is motivated to sell his knowledge of the flaw to whomever will buy it. And he motivated to make these sales ASAP, as the value of his ‘exclusive information’ will plummet as soon as it becomes less exclusive.

So the security parameter needs to vary with how long it takes until the first honest person finds a flaw14. How long will this be? We cannot be too sure, but 12 hours seems to be a reasonable duration.

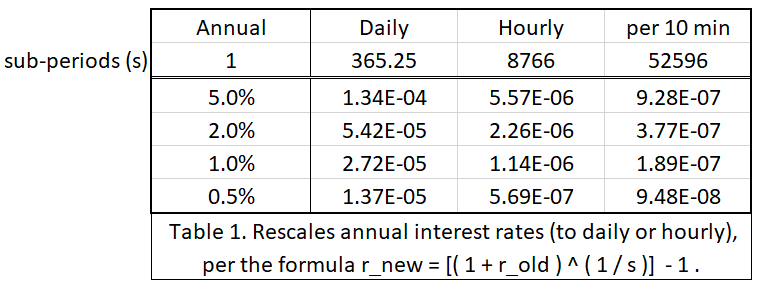

What is the cost of locking up a dollar of working capital for 12 hours? It depends on the market interest rate. Since an Honest Fred has no “risk” associated with this project, the rate should be the [theoretically-minimal] “risk free rate”, and since BTC is a deflationary unit of money, it does not need to appreciate to compensate the investor [to offset the inflation tax]. So the required rate of [annual] interest on this “project” could possibly be very low, it could be 2% or 1% – it depends on what other investment projects are out there [with this risk-reward profile]. Currently, nothing is out there, so the market rate could be arbitrarily close to zero.

Below I have rescaled some interest rates from annual to daily, hourly, and per 10 mins:

In addition to deciding the duration of coverage, a second security parameter is how much coverage one would like to buy. I have assumed $1000 worth. When a seller sets his $1000 up against a few cents, it implies that the seller earnestly believes that there is a >99.99% chance that the block is valid.

Finally, for ease of interpretation, I will assume that Sally always insures every blockheader. This helps compare her level of paranoia to that of a regular ‘full node’ user (who would also check every single block).

Thus, we can see the monthly cost of buying all of this invalidity insurance, for different interest rates.

And we see that it may cost as little as $29.93 a month.

Total Cost

Thus, the total cost of validating every block in this “negative” manner comes to $51.84 a month.

This cost is driven by two things: first, the number of Fullness Audits performed per block; and second, the security parameter choices (coverage amount, coverage duration) for Invalidity Insurance.

One could reasonably argue that each of these should increase as the network becomes more expensive (ie, as the “blocksize” increases). After all, if the block is larger, it becomes reasonable to pepper it with a proportionally greater number of Fullness Audits; and it may also be wiser to increase the ‘coverage duration’ for Invalidity Insurance.

If so, this would seem to contradict the purpose of using Fraud Proofs in the first place!

Cost-Scalability

However, I believe that one could also reasonably argue the opposite: that the value of $51.84/month could be stable indefinitely, or even decrease over time.

For example, an increase in the absolute number of independent full nodes, would inevitably mean that there would also be an increase in the absolute number of nodes running on disproportionately superior hardware/software. These super-nodes will detect threats sooner – through the process outlined above, some of them may monetize this detection.

It is even possible that greater absolute number of SPV nodes will make it profitable for “specialist validators” to emerge – and only a few of these are required to grant blanket protection to the entire community (a possible application of the “Many Eyes hypothesis”, or of “herd immunity”).

C. Partial Fullness

Sally does not necessarily need to validate every block, of course – millions of SPV mobile users are today getting along just fine, while validating zero blocks!

Certainly, in general, more validation is preferred to less, but Sally might opt to only validate a few blocks. Perhaps, when receiving money, Sally validates the block that contains her new txn, and the 400 blocks which precede it, and then the 20 blocks which follow it. Or, perhaps Sally just validates a few blocks at random.

9. Conclusion

Fraud Proofs address the problem of learning that a Bitcoin header is invalid (despite it being PoW valid). Such cases are very rare. In fact, I think that 100% of the historical cases were mistakes (ie accidental), and were corrected as soon as possible.

Moreover, this post expresses many ideas, and each of them would be its own medium-sized project. If blocks are easy for the layperson to validate, then working on fraud proofs is certainly a waste of time. However, if blocks are difficult-to-validate, then fraud proofs may be very useful.

To be honest with you, I wrote this post mostly as an “exhaust valve” to get these thoughts out of my head! They were driving me crazy!

But now that we’ve meditated I feel better. I hope you’ve enjoyed reading!

( Sunset art from Max Pixel)

( Sunset art from Max Pixel)

Footnotes

- The “Full” vs “SPV” distinction is actually not as sharp as might casually be believed. For starters, when a “full node” is downloading the next block, it is itself in SPV mode, with respect to that next block. And consider the case where 51% hashrate secretly runs a new piece of software (and, correspondingly, runs a new-but-compatible protocol) – one with a mandatory extension block. Then, despite intending to be a “full node”, you have been forced to become partially-full, and partially-SPV. If the miners later change the protocol back, removing the ext-block requirement, then you will return to being 100% full. But you will not be aware of having transitioned in either direction, and in fact you have no way of knowing. So, these terms only make sense if the protocol is fixed, so that is what I assume in this essay. In reality, however, the protocol can and does change; and miners are always allowed to run secret, customized software. ↩

- Well, each block that she wishes to “fully validate” by this SPV method. ↩

- For blockchains which are themselves sidechains, the inter-chain transfers also become Class I flaws. To be alerted to fraud, the sidechain SPV node would get two txns, the sidechain deposit and the mainchain txn that originated it. Then the ‘Sidechain Sally’ must check both blockchains (main and side) for Flaws. ↩

- The total per-block byte-cost is: “header + first_txn + last_txn + 2(32log_2(n))”, where “log_2(n)” is “ceiling of the log_base_two of the number of txns in the block”. Thus we have “80 + 1000 + 280 + 2(32log_2(5000))” in our example, or “80 + 1280 + 832”, or 2192. Notice that we do not need the bitmask for the coinbase, because we already know its exact structure (“always left”), but we might use it for ‘last txn’ (because it alternates between “right” and “self”). (This would be smaller than, say, encoding “self” as a branch-hash consisting entirely of zeros, as I have estimated it here.) ↩

- In practice, Sally and Fred might do one random number at at time. If so, their worst-case-scenario script size will be smaller, but they will need to do more audits. ↩ ↩2

- This is a simplification for the story. In reality Sally would not reveal the integers, she would instead reveal the randomness she used to compute the commitment (ie “open”on Wikipedia). ↩

- Each pairwise exchange can be quite customizable, and probably will be customized to [for example] improve privacy. But for my simple explanation, “shared H” is simple enough. ↩

- Recall that, at this point in the validation process, Sally already has the entire header, and knows that it meets the difficulty requirement. She only needs to evaluate the hashMerkleRoot. ↩

- Of particular concern is a situation where txn-validation changes over time (for example when we soft-fork-in a new OP Code) – previously valid [but not-included] txns may become invalid. Thus, if someone accuses one of these txns of being invalid, we would need to know the exact time, and consensus rules it had when it was included, vs now. What a nightmare! But for a given static protocol, whose txn-validation rules do not change, there is no problem (as I mentioned in footnote #1). Perhaps this can be solved by incrementing the block version number each time the consensus rules are changed via soft fork. Or else, it can be solved if Sally upgrades her software – she can stay in SPV mode, but she needs to be running the latest SPV mode to enforce the latest rules. ↩

- Ie, check that the formatting is intelligible, that the input scripts are valid, that sum(inputs) >= sum(outputs), etc. Everything that is checked during normal “full node” validation. ↩

- A four byte unsigned integer can count to 4.29 billion. So that enough to uniquely describe one point along a vector, as long as the blocksize does not exceed 4.29 GB. And, even if it does, we can probably use the modulus (ie, allow it to overflow), because it should be readily apparent, from the size of the Merkle tree, whether the block is <4.29 GB, <8.58, etc. As I explain later, the data does not actually need to be broadcast over the network at all, or stored. It is just about reaching the correct hashMerkleRoot ↩

- The intermediate nodes take on the role of intermediaries such as “insurance originators” or “reinsurance agents” – the first group sells insurance to end-customers, while planning to immediate sell the contract to a ‘real’ insurance agency; the second group sells insurance to ‘real’ insurance agencies, thus taking contracts (and risk) off of their hands. — — For Invalidity Insurance, one can think of the “evidence” txn that completes the script as just a larger and more complicated version of “R” [recall that R is a random number chosen by the buyer, who also calculates h(R)=H and builds a “circuit” of payments based on the same H]. The “evidence”, once revealed somewhere, will trigger all of the insurance payments in a given circuit – in fact, it will trigger all of the payments for all circuits everywhere [for a given invalid block header, of course]. — — For Fullness Audits, the “originators” would bear more risk, and could possibly extract a higher return as a result. This is because the originators [“Sally1”] would first need to Audit a real full node [“Fred”], until they are convinced that the full node really is full (in other words, Sally1 audits Fred until she is convinced that he is an Honest Fred). Sally1 can then safely sell Audits to, for example, Sally2. Sally1 won’t be able to complete the audit by herself, because Sally2 will ask for random txns that, by definition, neither of them will have. But Sally1 should be able to get these txns from Fred with a new audit. — — None of these techniques make any sense at current levels of blockchain scale. But, theoretically, if blocks become absurdly difficult to validate (perhaps because they were terabytes in size), these levels of specialization would start to become efficient. They would also tend to become more efficient as channel openings/closings become more expensive – this is clear from the ‘Sally2’ example above, where several headaches would be avoided if Sally2 just opened a channel with Fred directly. ↩

- Indiana can sell Class II flaws this way, just as easily as Class I flaws. He will merely offer to buy Fullness Audits at above-market rates. All of the reinsurers will flock to him, and he will collect damages from all of them. They, in turn, will immediately try to pull the same scam on anyone who hasn’t fallen for it already. So the critical information [that a specific parts of this block is missing] will still spread rapidly. ↩

- Notice that, by using smart contracts and free market trade, we have achieved some specialization of labor and the associated welfare gains. ↩