I’m Not an International Drug Dealer

| If you find WORDS helpful, Bitcoin donations are unnecessary but appreciated. Our goal is to spread and preserve Bitcoin writings for future generations. Read more. | Make a Donation |

I’m Not an International Drug Dealer

So Why Do I Need Privacy?

By Meltem Demirors

Posted April 15, 2019

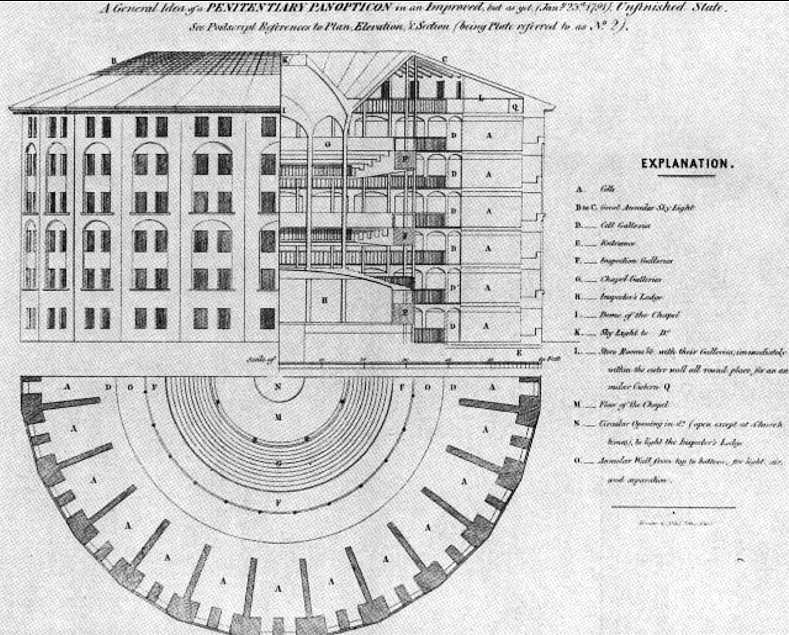

An overview of Jeremy Bentham’s concept for a panopticon — or the optimal prison design to inspire fear

An overview of Jeremy Bentham’s concept for a panopticon — or the optimal prison design to inspire fear

‘…a new mode of obtaining power of mind over mind’– Jeremy Bentham, 1798

The panopticon was a prison design conceived by the rationalist Jeremy Bentham, and detailed in his 1798 writings of the same name. As a feat of architecture, the panopticon served to create two illusions — for the prisoner, that there was no escape from surveillance at any time, and no ability to determine if one was being watched, and for the prison guard, the ability to surveil at her leisure, without detection, and disempower the individual.

For the panopticon to function, at its core, Bentham realized he needed to create a fundamental imbalance of power, and to enforce this power dynamic in every aspect of design. According to Bentham, the panopticon could be used for prison reform, hospitals, the insane asylum, but most importantly, for schools, as they could be powerful tools of social and psychological conditioning.

The idea of power through control has guided much of human history — waxing and waning from the rise of totalitarian regimes to their ultimate defeat at the hands of revolutionaries or mass exodus.

A Brief Foray into Dystopian Fiction

Ah, doesn’t attending crypto conferences make you believe our future will be a beautiful utopia, filled with tokens that only go up in value, and deFi products that make getting a loan as simple as posting your millions of ETH as collateral?

Let’s explore a darker future. A dystopia, perhaps. In my view, one of the best ways to understand the present is to imagine the future and what better way to time travel through different versions of reality than by reading science fiction?

In 1933, Aldous Huxley penned Brave New World, in which the miracle of science and technology had been embraced to keep everyone happy and complacent, buzzing on soma, a pharmaceutical drug dispensed like Pez by the state. At the time Huxley wrote the book, much of the conversation in intellectual circles was around how humanity would solve economic and social issues, and usher in the so-called “Age of Utopia.” Recall that at this time in history, Ford had just popularized industrial production (Ford is a Demi god in the book), and consumer credit was becoming popular with the rise of high value, mass produced goods. Huxley’s book was in many ways a protest against this idea of utopia, and the dark places it would lead us as a society.

Ten years later, after the horrors of World War II, George Orwell published 1984, which described a dystopian future far less comforting than Huxley’s, and was positively terrifying in many ways. Having witnessed the rise of Hitler’s Third Reich and the brutality of the industrial war machine (fueled by new technology), Orwell no doubt drew from a different set of inspirations than Huxley. The Allied powers were busy diving the world into “spheres of influence” and setting up new political, military, and economic alliances in Africa, the Middle East, and Asia in a new form of global colonialism fueled by debt and credit.

Since then, countless novels have been written with similar themes, and you’ve likely read them at some point in your life. What I want to point out here is that the idea of control in these two books is very different. Both rely on mass psychological control and conditioning, but in very different ways.

Huxley’s world was one of apathy. Orwell’s world was one of fear.

Huxley’s world was one of pleasure, derived from the sweet, sweet soma and the pursuit of hedonistic, basic desires. Orwell’s world was one of pain, or “a boot stomping forever on the face of humanity.”

Most critically, Huxley’s world was one drowning in useless information, where no one cared for facts, especially not unpleasant ones. Orwell’s world was one where information was limited and controlled.

Both apathy and fear are tools of oppression. And understanding how they are used is important to understanding where we might go next.

One notable theme among all of these novels is that a lack of willingness to subject to surveillance or subject to social norms somehow made a person guilty of hiding something. This idea is becoming more prevalent today, as the world divides into those who value privacy and those who believe it has no value other than crime or illicit activity.

The Politics of Privacy

I’ve been thinking more about privacy generally, and here are some of the responses I’ve been getting when I talk about privacy on Twitter:

Whenever there’s a conversation about privacy, the inevitable ask becomes “why do you need privacy?”

Let’s talk briefly about why we must have privacy as the default setting for all things in our lives.

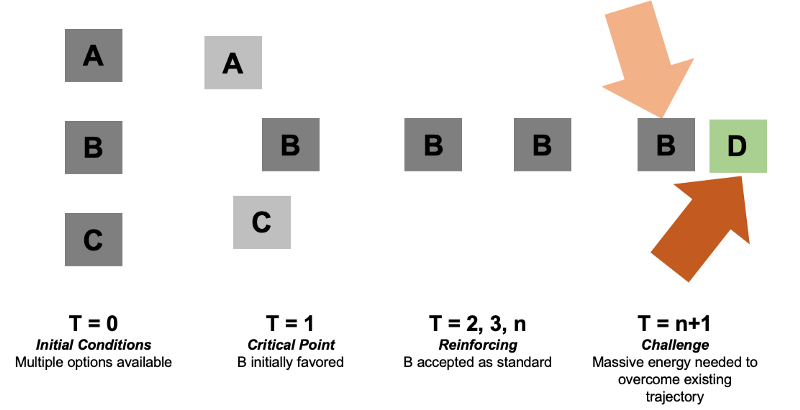

Here is a simple example. There are three options for a specific function, say, how privacy policies are served to you by an application you use. People are using different approaches, and it’s very exploratory. Over time, there seems to be clustering around A, B, and C.

A — you are given a simple, click through interface which highlights the most significant points of the policy in simple language, and for each type of term requiring consent, the options to choose “I CONSENT” or “I DO NOT CONSENT”

B — you are given a hyperlink that links to the Privacy policy and one button that says “I AGREE”

C — you are given no Privacy policy information in a visible way, but it is linked that the bottom of a website page

Now over time, B seems to be used more and more, so B is what is talked about, taught, regulated, standardized, what apps are designed around, what users are accustomed to, and therefore becomes a self-reinforcing “standard.” This goes on and on, and while there may be new approaches now and again, B is for all intents and purposes “the standard.”

Yes, this is a grossly simplistic view. Yes, path dependence is still a contested area of study.

Let’s say that by time n, the world has changed drastically, and a growing group of people recognize the standard B is actually harmful to their interests, and devises an alternative, D, that is better for this group’s interests. There will be a tremendous amount of energy requires to (1) demonstrate B is in fact inferior in some way, and (2) prove D is superior and install it as the standard.

This “energy” may include marketing, PR, regulation, legal action and other types of economic, political, or social activity, including acceptable and less acceptable practices, like bribery, collusion, or say, outright revolution.

Social and economic systems are inevitably far more complex than what is described. The point here is that larger systems that develop over time will be built on systems and knowledge gleaned from the past. So, in some respects, the potential paths for the future are constrained and defined by the paths open today, and the logic of the initial decisions made today.

So — imagine this. Today, at t = 0, you don’t think about your privacy often, it at all, and it really has no material impact on your life. So option B feels fine. Perhaps you even justify or support option B, by tweeting things like (yes, someone said this and yes, it makes me really sad because they probably believe it):

Tomorrow, you might find the circumstances of your reality changed, and you realize option B is in fact very much sub-optimal, and possibly even harmful to you, because of things like:

All of a sudden, if you attempt to protect your privacy, you have something to hide, and you must be doing something evil. You were complicit in creating the status quo, either through your consent or your apathy, so now you live with its consequences, unless there are other people with sufficient power, force, and energy to re-draw the boundaries of what is possible.

If we do not value our privacy today, and do not put into place mechanisms to protect, preserve, and enhance our privacy using technology, then we create the conditions for a future where our privacy has no value, and cannot be protected, preserved, or enhanced.

A Quick Detour to Cypherpunks

We can’t talk about privacy without talking about the cypherpunk movement. A cypherpunk is any activist advocating widespread use of strong cryptography and privacy-enhancing technologies as a route to social and political change. When the internet was beginning to become more commercialized, and as the world was converging on standards, a group of activists became concerned about the direction things were heading. The US government considered cryptography software to be a “weapon,” and would not allow it to be commercialized or sold.

In response, this group convened more formally on a mailing list, and one of the founders of the list circulated the Cypherpunk Manifesto, a short statement describing the purpose of the list.

We must defend our own privacy if we expect to have any. We must come together and create systems which allow anonymous transactions to take place. People have been defending their own privacy for centuries with whispers, darkness, envelopes, closed doors, secret handshakes, and couriers. The technologies of the past did not allow for strong privacy, but electronic technologies do.

We the Cypherpunks are dedicated to building anonymous systems. We are defending our privacy with cryptography, with anonymous mail forwarding systems, with digital signatures, and with electronic money.

The ideas expressed by the cypherpunks were by no means new. After all, countless revolutions in history have been inspired by anonymous or pseudonymous authors, artists, philosophers, and more. Cypherpunks formalized the relationship between technology and privacy, and effectively used advocacy (see the Electronic Frontier Foundation, the Open Privacy project), education, media, literature, art, legal code (many sued the US government, and several won), subversion (hacks, leaks), political dissent, code, and a variety of other tools to further their goals.

The ethos started as “cypherpunks write code,” but has evolved to mean something far greater than just writing and deploying software. Cypherpunks take action as individuals. They take personal responsibilityfor empowering themselves against threats to privacy, in whatever way they are capable.

We, as users of cryptocurrencies and other forms of applied cryptography in communications and computing, are doing something decidedly cypherpunk. We are participating in proving that these early prototypes have merit, and we are directly participating in their evolution to be usable at scale and en masse. These are important and essential experiments in the future of privacy preserving technology that can reach not just the privileged few.

In the future, as it was in the past, privacy may define the line between life and death for individuals, their families, and their social groups.

Privacy Today is an Illusion

In 2013, the world got a very bitter taste of an Orwellian future, when Edward Snowden, a private government contractor who was working for the National Security Agency, or the NSA, copied and leaked thousands of highly classified documents about global surveillance programs being run by governments involving payments to private corporations for access to emails, records, logs, and other private information about citizens. The breadth and depth of the surveillance state spanning not only the US, but also Europe, was not fully appreciated by the public until it was revealed by Snowden in this act of defiance, that was decidedly very cypherpunk.

So what do we mean when we use the phrase “surveillance capitalism?” (sidebar: listen to my podcast with Jill Carlson on this topic). Effectively, we are describing a new form of capitalism focused on commodifying behavioral and experiential data, which was pioneered by Google and later Facebook, and now used by nearly every technology company.

The rise of the internet and the movement of social life, commerce, communication, and human experience from physical space into the digital space has made it challenging for nation states to monitor a new and nearly limitless frontier (that wild west of the world wide web) and for corporations to implement existing business models. As a result, many companies now make money by providing a free or low cost product or service to consumers to gather data, and then selling that data to advertisers, governments, and other buyers.

Girls Just Wanna Have Privacy

Privacy, like anything else, is a topic that must be learned. If it feels overwhelming, it’s because it can be. Today, obtaining privacy is a Herculean feat that requires all sorts of trade-offs between usability and privacy. Tomorrow, I believe privacy should be easily accessible to anyone who desires it.

There are three types of privacy I believe must be preserved —

- Privacy in Economic Interactions, meaning who we send money to, how, when, in what amount, and why is something we have a right to keep private to ourselves and the recipient

- Privacy in Movement, meaning we should be able to move about physical, digital, and virtual space with anonymity, and we should be able to enter and leave spaces, whether in real life or online, without giving out identifying information

- Privacy in Communications, meaning we should be able to conduct conversations with certainty that they will remain private, and that we should be able to abstract our identity from our communications both in the physical world and online

Today, your degree of freedom in any of these is determined by a number of factors including where you live, what platforms and applications you use, your understanding of how to increase or decrease your privacy via use of additional tools like VPN, and the level of surveillance an unknown third party may want to exercise on you — just to name some. There are factors that are largely within your control, and factors that are outside of your control.

Tomorrow, freedom and privacy needs to be a default setting. We must take it upon ourselves to educate, advocate, build, and promote tools that preserve privacy.

Cryptocurrencies and Privacy

So how does this relate to the world of crypto?

By now, hopefully we all know this one fact — Bitcoin is not anonymous. It is pseudonymous. The blockchain is a public ledger — meaning anyone can download it, and since the earliest days of the bitcoin community, people have built tools to de-anonymize bitcoin users and link the blockchain pseudonyms ie wallet addressed with real people and places.

There are of course tools you can use — mixers, tumblers, and other programs to obfuscate the flow of funds, but the ability for cryptocurrency users to stay private is only secondary to the ability for companies to build business models violating this privacy so they can sell data to exchanges, regulators, and enforcement agencies.

But the future belongs to those who build it. And we have a big fight ahead.

Crypto is about freedom.

It’s not about creating a new revenue stream for Wall St or delivering big IPO returns to investors. Those might be nice second order effects, but I reject the notion that this is the primary goal.

Crypto is about privacy.

It’s not about creating a dystopian corporate digital currency on a private blockchain so you can guzzle Starbucks on piles of debt while you mainline Facebook and Instagram like a human click farm.

It’s not going to be easy, but it’s going to be worth it.

And as one does, I’ll end with a quote, this one from a Russian dystopian sci fi novel entitled “We”, published by Yevgeny Zamyatin in 1924.

“There is no final one; revolutions are infinite.”

The battle for privacy won’t be fought in one medium, at one time, or in some grandiose, defining way. The battle for privacy begins with the choices we make every moment — both small and large — and the manner in which we hold ourselves and others accountable.

So what will you choose?

Choose yourself.

Choose privacy.

Some Starting Resources

- How to Be Invisible (Book) by J.J. Luna

- Smart Girl’s Guide to Privacy (Book) by Violet Blue

- EFF — Choosing a VPN That’s Right for You

- Tripwire — Why OPSEC is for Everyone

- Kaspersky Lab — 10 Tips to Improve Your Internet Privacy

- Berkeley — Top 10 Secure Computing Tips

- Jameson Lopp — A Modest Privacy Protection Proposal

- NIAIA — Individual OPSEC & Personal Security — A How To Guide