Exploring Liquid Sidechain

Exploring Liquid Sidechain

Joe Kendzicky

Posted November 15, 2018

Overview

In 2014, a group of notable Bitcoin developers published Enabling Blockchain Innovations with Pegged Sidechains. This whitepaper outlined a very high level framework on how sidechains might look, but lacked significant technical specifications with regard to implementation. Two years later, a group of Blockstream researchers released Strong Federations: An Interoperable Blockchain Solution to Centralized Third-Party Risks, describing how many of the aforementioned concepts could be implemented utilizing a semi-trusted Byzantine fault tolerant consensus mechanism referred to as strong federations. Strong federations fall somewhere between the extensive decentralization guarantees provided through Nakamoto style consensus, and the significant trust implications of centralized exchange services. In this article, we explore one of the first iterations of federated two-way pegs: Liquid, a settlement network primarily directed towards exchanges and other liquidity providers.

What do sidechains provide?

Sidechains allow us to take an asset that traditionally exists on a remote chain, and transfer it onto a different blockchain, without distorting the asset’s integrity. For example, imagine there were a way to move bitcoin onto the Ethereum network. Though it is impossible to actually move a BTC onto another chain, we could create a synthetic ETH token collateralized by real bitcoin on the mainchain. Anyone holding the ETH token could exchange it at any moment for real BTC, and thus the two assets would exhibit a 1:1 (or near 1:1) peg.

Having this capability opens the door to many different form of unique cross-chain interoperability features, such as executing smart contracts across different blockchains. Sidechains always involve a source and destination blockchain. A peg is established between the chains, meaning assets from the source are converted into entirely new ones on the destination, at a fixed ratio (usually 1:1). Since the destination sidechain is its own independent blockchain, destination tokens can be transferred freely among network users, just as they would inside of the source network. Users are free to reconvert their sidechain tokens back into mainchain ones at their full discretion. Usually these destination tokens provide beneficial features that the source chain cannot: privacy, Turing-completeness, fast settlement or low fees. In our scenario, Bitcoin serves as the source blockchain, with Liquid as the destination.

Functionaries

To begin, let’s first start off by defining two important figures within the Liquid ecosystem:

1) Watchmen- play an important role serving as gatekeepers, regulating the transition of assets between the source and destination blockchains.

2) Blocksigners- contribute to the creation of new blocks, similar to miners in proof-of-work systems and validators in proof-of-stake systems

Both of the above parties fall under the collective roof of functionaries. Functionaries are a privileged set of network actors who mechanically perform defined network operations. By privileged, we are referring to a fixed group of permissioned actors who have the capacity to fulfill these roles. Contrast this to open system like Bitcoin, where any network participant has the ability to contribute to the consensus process through open mining operations.

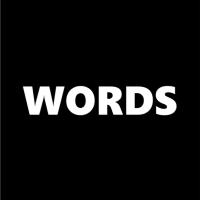

Entry into the sidechain is a process referred to as a “peg-in”, where Bitcoin users deposit BTC to a specially constructed address, called a pay-to-script-hash (P2SH). Traditional Bitcoin scripts usually just require the spender to produce a valid signature from a private key. This private key corresponds to the public key in which the funds are encumbered. P2SH requires the spender to produce a few more pieces of information outside of just a digital signature. The scripts required to spend the LBTC reads: <11 of 15 Multisig> OR <4-week timeout + 2-of-3 Multisig>. We will touch on this construct and its importance in later segments.

Once bitcoins are sent to the P2SH address, the depositing party loses sovereignty over them. A confirmation period ensues to guarantee settlement of the funds, preventing against the risk of a chain reorganization or double spend attack. Without sufficient confirmation that the pegged-in BTC has settled, an attacker might be granted LBTC prematurely on the Liquid sidechain, while their BTC manages to “escape” on the mainchain through a reorg or doublespend. Such an event would lead to a situation where LBTC and BTC no longer maintain a 1:1 pegged ratio, thereby granting the attacker free money.

Liquid requires 102 BTC confirmations for the transaction in order for the LBTC to become available. This seemingly ambiguous number exists for 2 reasons:

- 100 blocks as overkill to guarantee that a reorganization is probabilistically impractical. This is the same depth that the Bitcoin protocol requires miners to wait before being able to spend their coinbase rewards when they solve a new block. While 6 confirmations is usually considered sufficiently strong for a BTC transaction, there have been a few rare occasions of orphaned blocks extending much deeper (though this usually only happens during some obscure bug interval). For example, the March 12, 2013 fork extended 31 blocks, while the 2010 value overflow bug extended an orphan 53 blocks.

- 2 blocks to ensure every node agrees on the 100th block. Given our first principle, conflicting views could exist amongst the network nodes as to which block that 100th block is, were a chain split to happen after the 99th mined block. By extending depth an additional 2 blocks, we allow the blockchain some leeway time to re-converge if necessary.

It is important to understand that the BTC on the Bitcoin chain is not destroyed. Rather they remain “frozen” in the multisignature account until the corresponding LBTC are revoked off the destination chain, and proof has been illustrated that such action has taken place.

Examining LBTC Creation

BIP 32 introduced a set of important features that allows for hierarchical wallet structures. Hierarchical frameworks are useful because they allow for deterministic construction of new public keys (and therefore unlimited new BTC addresses) without needing underlying exposure to the public key’s corresponding private key. This is a great feature for online merchants wanting to incorporate Bitcoin payments at point of sale. They can upload something called the master private key into their web server, and compute sub-domains of new bitcoin addresses directly from this master public key. Previously, they would have had to either expose their private key onto the server in order to derive new addresses (dangerous) or generate a bunch of new private/pub key pairs offline, then manually import the addresses over to the server (inefficient).

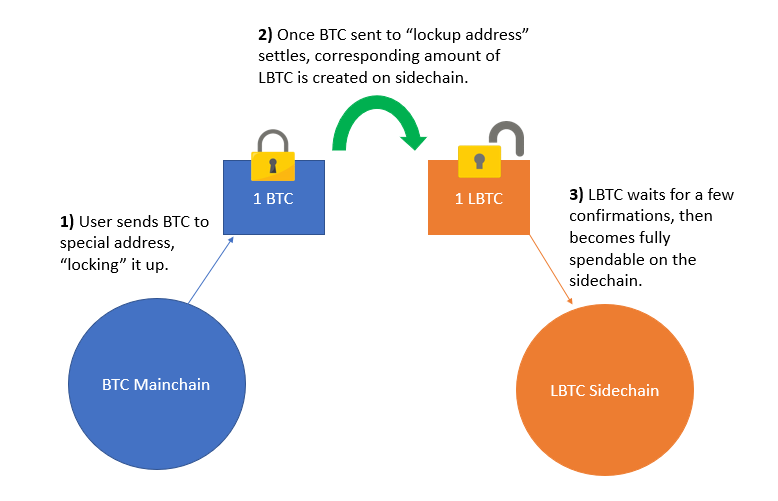

We can think about the construction of new LBTC in a somewhat similar fashion, though some technical differences remain. Essentially what the user is doing during a Liquid peg-in transaction is performing some cryptographic tricks to derive a new public key (call this A’) directly from each functionary’s existing public key (call this A), in a similar way that BIP 32 allows one to derive a child public key from a parent public key without needing involvement from the corresponding private keys. The user then sends their BTC to a special P2SH address that references all these new A’ addresses. This P2SH transaction reads very analogously to a multisignature clause. It says “if 11 functionaries (out of the 15 possible) prove ownership of the A’ public keys outlined in this template, by collectively signing off with their corresponding a’ private keys, they can unlock and spend the funds.”

After issuing the Bitcoin P2SH transaction, the user needs to actually let the functionaries know that the transaction occurred. Up to this point, the functionaries still have no idea that they’ve been paid; everything has been done on the user end. The user now needs to turns around and hand this new template of A’ to the functionaries, so that they can reverse engineer the corresponding a’ and gain access to the locked up BTC.

The way the user goes about doing this is by creating a LBTC transaction from scratch. The inputs to this transaction will look a bit funky, because they reference no previous LBTC output (think coinbase transactions when miners mine a new BTC block). Instead, the LBTC transaction embeds the original BTC transfer as its input, illustrating proof that the user previously surrendered their BTC rights into the hands of the watchmen. Seeing that they’ve been paid via the A’ public keys and the 102-block confirmation period has passed, these functionaries can reverse engineer back to its corresponding private keys a’ and assume control over those funds. With all the boxes now checked, the functionaries will validate the peg-in LBTC transaction by including it into a Liquid block.

Once the new LBTC are unlocked onto the Liquid sidechain, users are free to engage in transactional behavior at their full discretion. Very similar to the traditional Bitcoin blockchain, LBTC are governed by the underlying private keys of their owners, are immutable digital assets, and publicly auditable through a distributed ledger. LBTC also possess certain characteristic advantages over the tradition BTC network. Examples include resistance to reorganizations, 1-minute block times, deterministic block intervals (instead of dynamic block production), and ring confidential transactions.

When users are ready to convert their LBTC back into BTC, they engage in the “peg-out” process. This involves transferring their LBTC to a Liquid address where they wait for 2 block confirmations. Because there is no threat of reorganizations occuring on the Liquid network, we don’t have to wait the meticulous 100-block period as we did during the peg-in process. After 2 Liquid blocks have ensued, watchmen sign off the 11 of 15 transaction on the Bitcoin mainchain, transferring money to the entitled owner, and subsequently destroying the LBTC in the process.

Peg-Out Transactions

When funds are ready to be transferred out of the Liquid sidechain and back into the Bitcoin network, the LBTC needs to be destroyed and the corresponding BTC released from multisig via the Watchmen efforts. In an effort to preserve privacy and mitigate security risks, functionaries control a Peg-out Authorization Key list that ensures outgoing BTC transactions are sent to a bitcoin address controlled by an authorized party. However, this creates an unfortunate situation where any user needing to redeem their LBTC to BTC must do so through an exchange or partner with a block signer. Essentially what we have happening is the user sends LBTC to a burn-style address, then waits 2 confirmations for that LBTC transaction to settle. The exchange sees the transaction as confirmed, pays out the user from their own hot wallet, and is subsequently “reimbursed” by receiving the BTC from the functionary multisig.

The intention of this strategy is aimed to reduce the risk of theft on the sidechain, which would consequently lead to theft on the mainchain. Peg-out addresses which the Watchmen pay out to are air-gapped cold addresses maintained by the exchanges. These addresses are constructed in a way that make it incredibly difficult to compromise the underlying private key.

Emergency Recovery Process

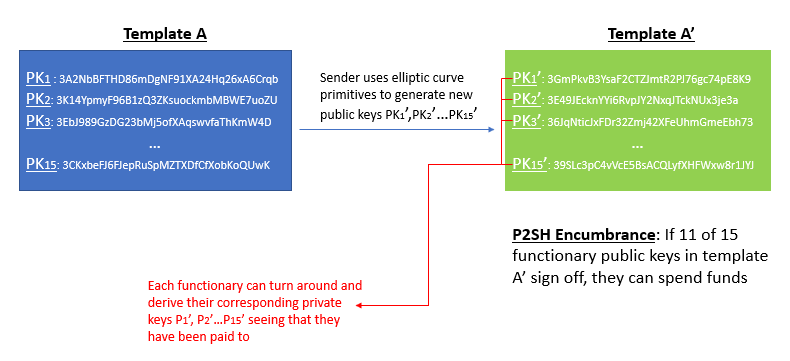

Remember how we earlier touched on the <11 of 15 Multisig> OR <4-week timeout + 2-of-3 Multisig>_P2SH that keeps our Bitcoin locked up? The < _4-week + 2-of-3 Multisig> clause serves as an emergency recovery component in a situation where ⅓ of the network goes offline or begins engaging in nefarious behavior. If such an event were to take place, the network would stall out and fail to produce additional blocks, but the Bitcoin on the mainchain would be stuck in escrow if the 11 of 15 component is not capable of being overcome. So, we introduce a second clause that consists of a completely different set of 3 emergency keys which can be used if (and only if) the network sits idle for 4 weeks, and we only need 2 of those 3 signers to sign off and move funds out. These keys are controlled by a totally different set of functionaries (undisclosed who these participants are for security reasons, but presumed to be geographically distributed attorneys) and can only be utilized after the 4 week lapse. Because of this, functionaries need to “churn” the locked BTC on the 27th day by sending it to to a new peg-in address they control, as a way to reset the timelock. Otherwise, 2 of the 3 emergency component would go into effect, and functionaries could then collude and steal user deposits.

Consensus Algorithm

In Bitcoin, miners bundle transactions into aggregated units called candidate blocks, with each candidate displaying a unique header. These miners subsequently perform redundant SHA-256 hashing on such headers, tweaking the nonce field element after each iterative hash, until someone in the group arbitrarily produces a digest below a predefined target. The winning party broadcasts their solution to the rest of the network, who can validate its authenticity. If the rest of the network is satisfied by the proof, they simultaneously adopt the winning party’s candidate block as the “official” ledger state.

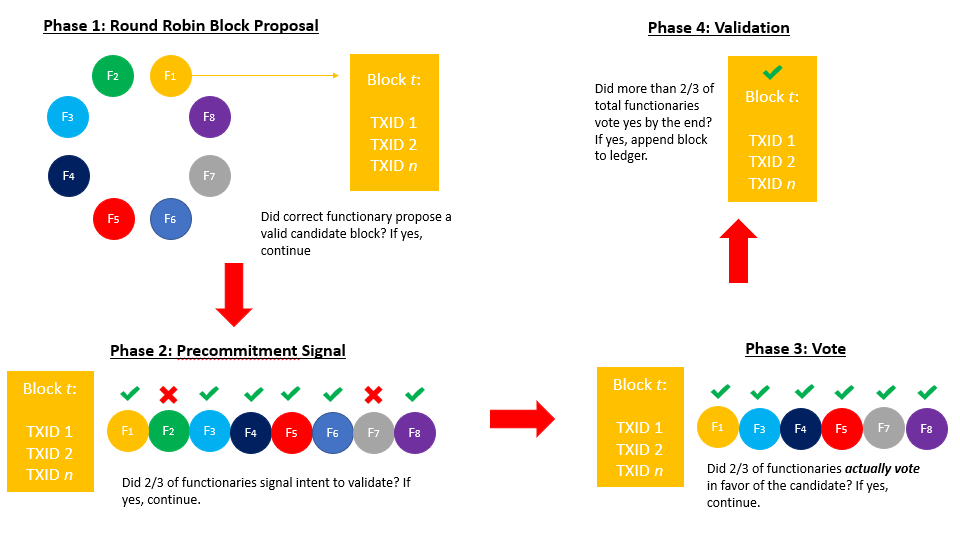

Liquid does not depend on a dynamic hashing contest to reach network consensus. Rather, it involves a Byzantine fault tolerant, round-robin multisignature scheme amongst a privileged group of blocksigners (the second group of functionaries we touched on earlier). These blocksigners inherit a role similar to miners in PoW, or validators in PoS; their job is to contribute to forward propagation of the network by creating new blocks, and thereby validate transactions. By limiting the number of candidates capable of contributing to consensus rather than remaining an open consortium, the network is able to achieve universal consensus with lower latency, faster block intervals, and lower computational burdens. In many respects, the consensus algorithm replicates features found in the Ripple RCPA protocol, described here. The system involves a round-robin style where blocksigners rotate turns proposing candidate blocks. After the blocksigner issues a candidate, their peers signal intent to validate the block through a precommitment scheme. At the conclusion of the precommitment round, if 2/3 or more of the group has signaled favorably, each member proceeds by actually signing the k of n block with their key. If the number of signees is greater than 2/3 then the block is accepted by the network and written to ledger. Note that the number of blocksigners who commit to sign and those who actually end up signing may be slightly different. For example, if someone loses connection midway through the process. The system rotates to a different block signer who proposes a new candidate block, and the process repeats.

A compelling feature of the Liquid BFT is that a reorganization after two block’s depth is impossible (assuming no malice or bugs). If a candidate block fails to reach its designated threshold, or the selected functionary for that 1-min time frame fails to perform their duty, no block for that interval is produced. Those transactions then carry over into the next candidate round. Users are not at risk of the network forking into two conflicting chains. The tradeoff to this scenario is that the network has the potential to stall out if blocksigners continually fail to reach the designated threshold required to append a new block.

Privacy

Liquid offers privacy features to users by embedding Ring Confidential Transactions directly into the protocol. Ring CT shields important metadata such as the transactional output values along with the destination/recipient addresses. Similar to Zcash, Liquid users have the ability to broadcast transactions on a transparent or confidential basis. However, the protocol automatically issues transactions on an opaque basis by default; users must manually configure transactions if they want the metadata to be publicly exposed. When dealing with CT’s, only the participants that have access to the what is known as the blinding key are capable of viewing such information. This key is limited to the sender and recipient of the transaction, but can be passed along to other parties as they like.

The benefit to such a system is that it allows network participants selective disclosure. Selective disclosure gives network participants the ability to preserve the integrity of information that may be sensitive to their business or trading operations, while simultaneously offering the ease and flexibility of sharing this data in a frictionless manner with authorized parties (business partners, auditors, government officials etc). A great example of where CT might prove beneficial is for traders who are looking to place large orders. Since the Bitcoin blockchain is available for public audit, external actors can witness the movement of large funds to an exchange and front run, driving up the order book and forcing the trader to incur slippage.

Challenges

While there are many positive implications of LBTC, it also comes with its share of tradeoffs, especially for node operators. Some of the biggest performance limitations include:

- 1MB block size (relatively low)

- 10x CPU requirements over BTC

- 10x bandwidth requirements over BTC

- 10x transaction sizes compared to BTC due to CT features. However, drastic improvements are on the horizon with the implementation of bulletproofs (see XMR)

- UTXO sets could grow exponentially larger

- Synchronization and new node bootstrapping could get significantly more difficult and computationally expensive

- Higher trust implications (discussed in later segments)

Issued Assets

Another interesting feature Liquid provisions are Issued Assets. Issued Assets are analog to the ERC-20 standard commonly found on the Ethereum network, and are uniquely native to the Liquid sidechain. Any sidechain participant has the ability to issue and transfer their own Issued Asset with other users inside the Liquid ecosystem. The provisioners can elect for supply to remain permanently fixed, or maintain discretionary autonomy over its future inflation schedule. This is accomplished through a feature called the reissuance token, which subsequently can be constructed using a multisignature scheme and dispersed among numerous parties. Different scenarios where these assets may come into play is if an issuer wants to distribute some form of tokenized security across a highly liquid and interconnected network: gold storage tokens, fiat backed tokens, shares in a company, collectables, ETF-related products etc.

Risk Mitigation

If not already obvious, some attack vectors lay present. Functionaries are not only required to communicate with one another, but sometimes depend on these communication broadcasts in order to determine how they themselves should act in specific situations.For example, during the precommitment of the consensus algorithm, if a blocksigner themselves signals “Yes” for a specific candidate block, but sees that not enough signers signaled accordingly to meet the X target, they will sit out during the actual signing phase. If an attacker is capable of infiltrating more than 1/3 of the blocksigners, they could force a network stall out simply by refusing to vote, and preventing the require 2/3 consensus to be achieved in order to create a block. If they are capable of corrupting 2/3 of the blocksigners, they could validate nefarious blocks.

To prevent against such threats, when new functionaries join the network, Blockstream provides these agents with proprietary hardware to conduct network operations. This hardware consists of two components: a server with precompiled software to perform network operations, and a “offline” hardware module to store functionary keys. These hardware boxes are designed in a way that purposely limits their vulnerabilities to network stack exploits which could compromise the consensus process. Each functionary server is presumably stored in a secure, anonymous location, and only communicates to other functionary servers via Tor. Tor connections provide security by obfuscating the server’s IP address, reducing the risk of physical theft or tampering while simultaneously hedging against potential DDOS attacks on the server. RCP calls are severely restricted and the hardware is specifically configured to only allow incoming SSH connections when a button on the box is pressed. Meaning to make any software or network alterations, you need to be in physical location of the hardware, severely limiting attack vectors.

The most obvious threat to the Federation is the group of functionaries themselves. At the end of the day, users transacting across the Liquid network are forced to trust the functionaries. If more than ⅔ of the functionaries collude, they have the ability to steal user funds. However, given the game-theoretic incentive models at play, the probability of this happening seems relatively low. First and most obvious, these functionaries are not anonymous parties but publicly recognized institutions that operate in jurisdictions where laws exist. The probability of a set of functionaries openly colluding to steal user funds without being subject to legal recourse are slim to none. Second, with regards to covert collusion (playing it off as a hack), exchanges would naturally be disincentivized to steal from their customers, thereby driving away core business revenues (exchange fees), unless the payoff from the attack outweighed the cost of collusion plus opportunity cost of capital relinquished from future business revenues. Consider also the fact that the cost of collusion grows logarithmically with respect to number of total parties colluding. Unless the Liquid network grows to a considerable value, it is highly improbable scenario this happens, given how much money these businesses are making on trading fees.

Workflows

Liquid’s audience will primarily cater towards exchanges, market makers and other large liquidity providers, along with their users. While Issued Assets might offer compelling opportunities for asset issuance, the scripting capabilities offered by other blockchain systems and higher levels of throughput make it a highly competitive and saturated market. Traders on the other hand are in fervent demand for quicker asset settlement, illustrated through the radical price discrepancies that exist across premier exchanges. Being able to move significant volume across platforms will reduce friction and costs for traders and liquidity providers alike, while simultaneously improving overall market efficiency by reducing spreads between exchange indexes.

Conclusion

While not the most bleeding edge implementation of sidechain technology, Liquid addresses a legitimate and current need in the cryptoasset ecosystem by allowing traders and exchanges to provision liquidity and settle transactions in short order. Benefits include embedded privacy through confidential transactions, higher throughput, faster settlements times, and ability to issue custom assets. Drawbacks include increased computational costs to node operators, higher degrees of trust than Nakamoto consensus, and counterparty risk of stolen or irrecoverable funds. If successful, Liquid validates the sidechain model, and opens the Bitcoin blockchain for increased functionality in further implementations. This no doubt comes with certain risks, but is a development challenge worth pursuing given the non-coercive nature of this technology.

Many thanks to Allen Piscitello from Blockstream , Pietro Moran and Hasu for their contributions to this piece!