Discovering Bitcoin: A Brief Overview From Cavemen to the Lightning Network

| If you find WORDS helpful, Bitcoin donations are unnecessary but appreciated. Our goal is to spread and preserve Bitcoin writings for future generations. Read more. | Make a Donation |

Discovering Bitcoin: A Brief Overview From Cavemen to the Lightning Network

By Giacomo Zucco

Posted September 2019

Welcome to the introduction to a series of seven articles, entitled “Discovering Bitcoin: A Brief Overview From Cavemen to the Lightning Network.”

“Did You Just Say Seven?”

I know what you are thinking, dear reader: Seven articles outlining the history of Bitcoin is too much for your busy schedule and too little to do justice to such an ambitious subtitle. As for your schedule, just relax: Today is Monday and, before next Sunday, you have exactly seven days, one for each article. Bitcoin Magazine suggested that I keep each article at around 1,200 words: Based on the average reading speed of an adult (265 words per minute), that’s less than five minutes per day! You can find them, believe me. Also, by the end of this introduction, you will have already read 1,200 words, which aren’t even included in the total count, since this is just the introduction. Yes, I scammed you. SFYL. As for the pretentious subtitle, I believe that these seven brief articles will be enough to develop — if not a deep knowledge of Bitcoin (an intricate maze of distributed systems engineering, open source development, applied cryptography, Austrian economics, information security and more) — at least a very high-level overview of the purposes it was designed to fulfill and of the reasons why it is structured the way it is. I chose this title not only because I intend to present the subject as a process of discovery but also because many of the best Bitcoin books and conferences are titled with a gerund (Mastering Bitcoin, Programming Bitcoin, Grokking Bitcoin, Inventing Bitcoin, Understanding Bitcoin, Scaling Bitcoin, Breaking Bitcoin, etc), so I wanted to respect the tradition.

Original Vision: The “Five Ws”

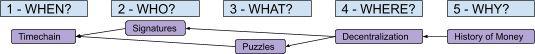

One of the challenges in trying to explain Bitcoin — its purpose, its structure and how the former conditions the latter — is deciding where to start. Allow me to bore you with some personal background here to justify my choice. The first few times I had to select some conceptual map, back in 2014, I opted for the famous “Five Ws,” an established information-structuring technique that Wikipedia tells me dates back to Aristotle himself!

When?

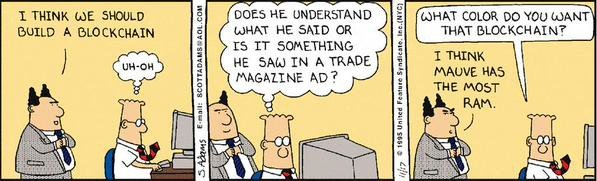

I decided to put the “When?” part first, to frame the actual necessity for a so-called “blockchain” (the ugly but also popular word sometimes used to label Bitcoin’s “timechain”): Basically just a time-related tool needed to establish a canonical ordering and to enforce a unique history in the absence of any central coordinator. Since the term had, by then, already become an abused buzzword, I considered it important to stress that everything a “blockchain” does is to answer questions based on “when” (specifically: “When can I reasonably consider this transaction as practically irreversible?” and “When was this unit of value added to the ledger relative to others?”). Bitcoin only needs a “blockchain” to prevent double-spending of valid transactions and to keep the supply growth rate under control in a decentralized setting.

Who?

But what are those “valid transactions”? In order to explain the ownership scheme in Bitcoin and the role of digital signatures, I introduced the “Who?” part, trying to provide my clients with an introduction to public key cryptography and to some general cybersecurity practices.

What?

In order to clarify concepts like “proof of work,” algorithmic difficulty adjustment and finite total supply of virtual “units,” I introduced the “What?” part, trying to deliver a basic introduction to client-puzzle functions and to some theory of value, as well as to answer questions like how the supply growth could be algorithmically controlled?

Where?

But why bother with “decentralized settings” anyway? Since there are central “coordinators” in most architectures, it would be reasonable to leverage them to provide a relative and unique chronology (no inefficient “blockchain” needed), to manage identities (no need for digital signatures, with all of their UX and security challenges), or to issue digital receipts for physically scarce goods (no need for a slow and painful price-discovery process to assign some value to intrinsically digital scarcity). The “Where?” part was used to clarify that our assumption was a system with no single point of failure, designed to avoid the fate of political censorship which affected centralized predecessors of Bitcoin, like E-gold.

Why?

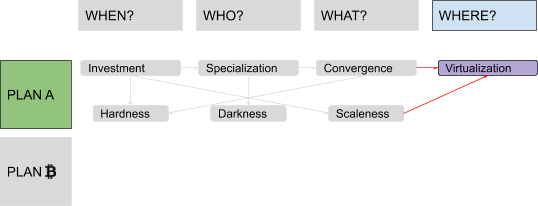

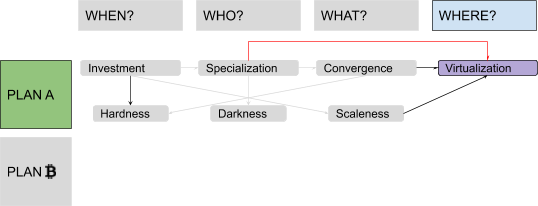

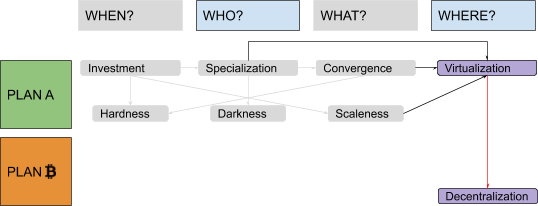

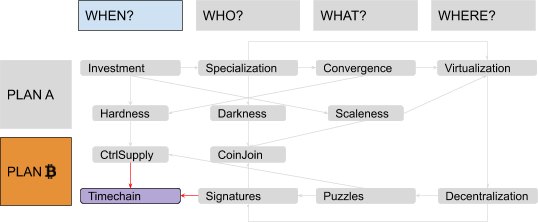

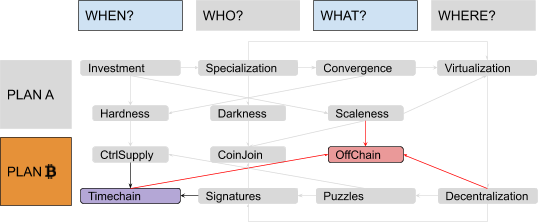

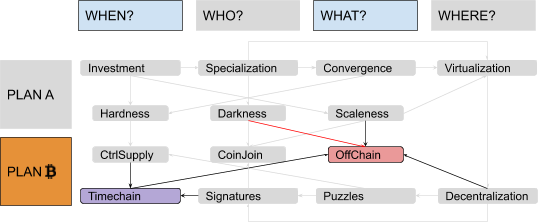

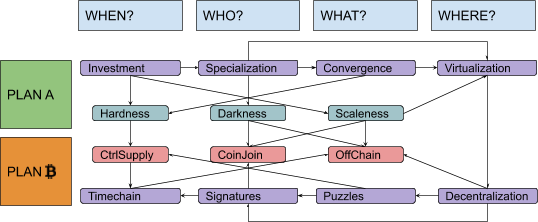

And what about the reasons for such political censorship? I moved then to the “Why?” part, where I tried to give a quick overview (more logical than historical) of the evolution of money: from stored consumption goods, to barter, to commodity-money, to free-banking representative money to monopolistic “fiat” money. The lessons were usually arranged more or less like this (the arrows represent a logical dependency, “We need the thing on the left because of the right”):

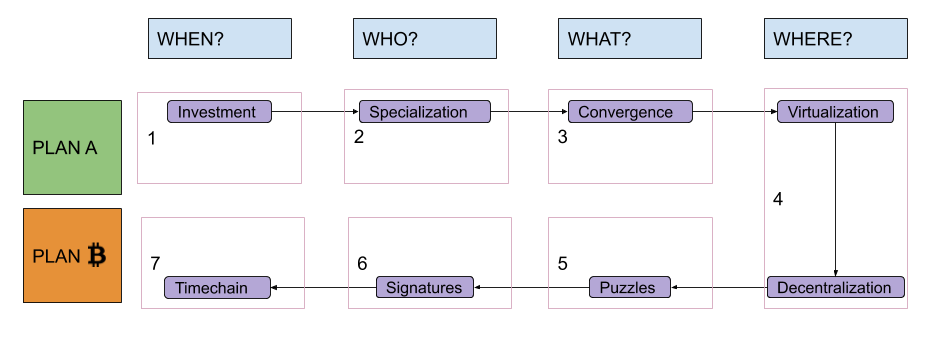

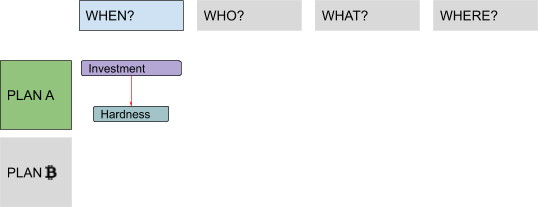

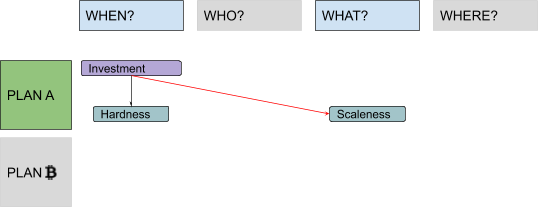

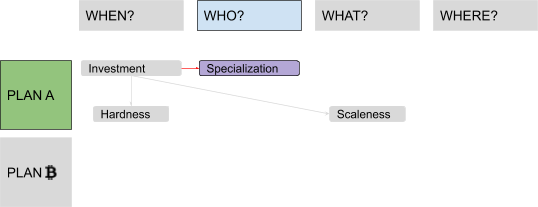

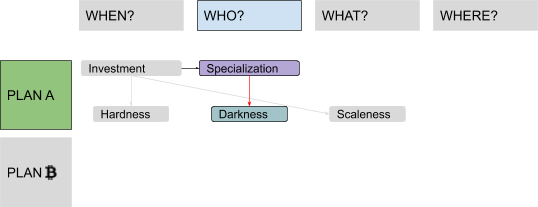

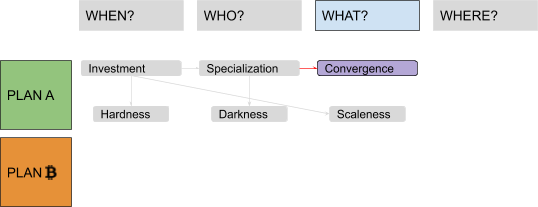

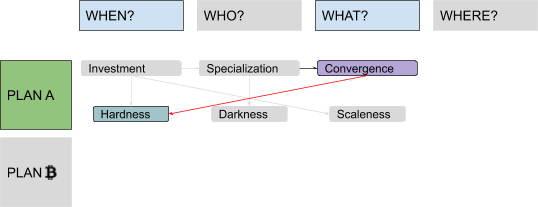

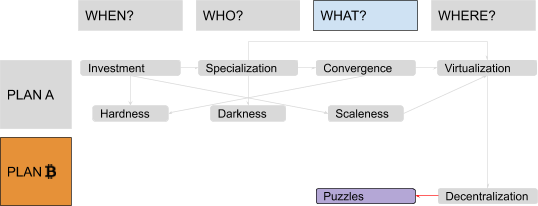

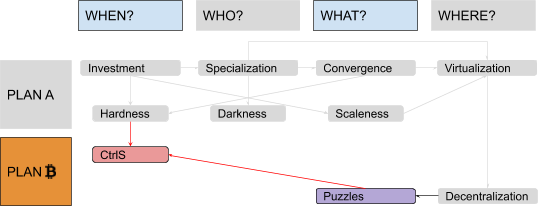

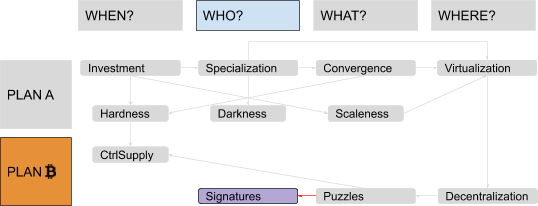

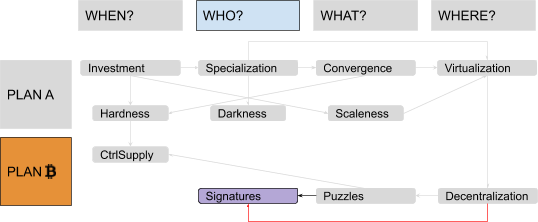

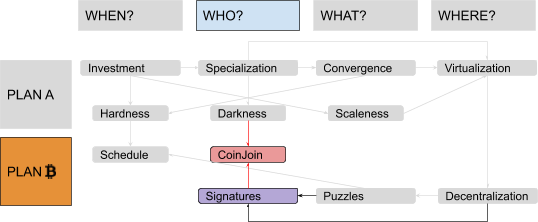

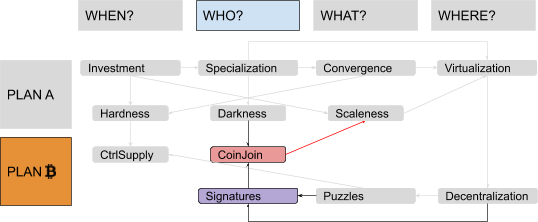

Upgrade: Four Ws, Two Plans

There were two problems with this model, the first being ordering: Each step was presented as necessary to “fix” the next one, in a sort of reversed causal chain, but the full picture became clear only at the end. It would have been more natural to flip it, starting from some monetary history in “Why?,” going through failed attempts at building centralized alternatives to fiat money in “Where?,” introducing decentralized value issuance in “What?” and decentralized ownership transfer in “Who?,” and finally ending with decentralized unique chronology in “When?” The second problem was the amount of information packed inside the “Why?” part. A lot of possible subsections, ironically, fitted quite well in the four remaining “Ws”: discussions about saving and investment fit pretty well in a “When?” section, discussions about exchange and specialization in a “Who?” section, discussions about convergence and liquidity in a “What?” section and discussions about virtualization of value by trusted central parties in a “Where?” section. Solving these problems would have required my audience to remain open-minded and focused while I ranged from cavemen to central banks. I couldn’t afford, back then, to keep them waiting for the “blockchain” meme for so long. But now I can. I guess that means, dear reader, that you will endure four (pseudo)historical articles before I even introduce the very first bit of cryptography! Stay strong! I labeled the first part of this series, ranging from fish-eating cavemen to modern monetary systems, “Plan A,” since it represents the first attempt at developing a monetary technology, characterized by a progressive centralization and by a very unhappy ending: fiat money. The second part is labeled “Plan ₿” (yes, you guessed it: the “₿” stands for Bitcoin): It starts from the messy situation that Plan A got us stuck in, approaching state-of-the-art Bitcoin development. The “Where?” part is the conjunction (and turning point) between the two plans. Something like this:

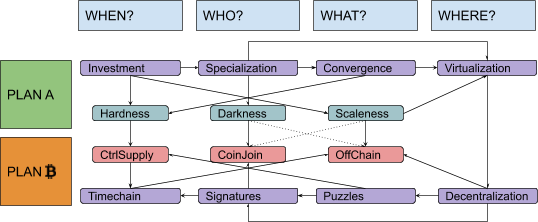

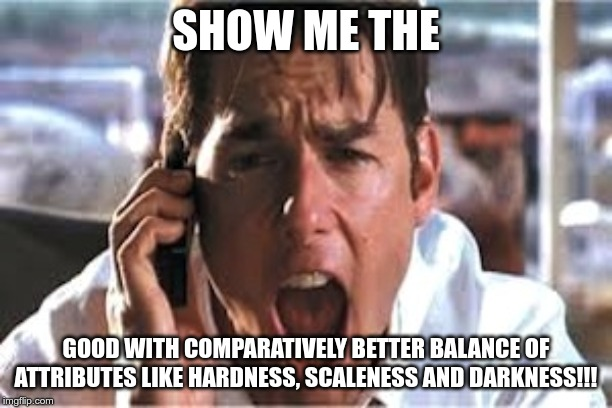

Trigger Warning!

In this series, I will often prioritize conceptual symmetry over economic rigor and technical accuracy. I will privilege logical connections over real-world chronological sequences, both in relation to monetary history and to technological development. I will commit terminological abuses that would make most economists and developers cringe, particularly when I discuss money attributes (where I will use an almost-made-up word: “scaleness”) and implementation paradigms (where I will abuse the term “CoinJoin” to address Bitcoin’s UTXO-model in general). No spoilers, but the overall map of logical connections should look something like this:

All the articles will include beautiful illustrations by @CryptoScamHub, of Bitcoin Twitter fame, in his signature “toxic” style. So, are you ready? Cancel all of your appointments for the next week. Or, at least, remove five minutes from one of them, each day. See you next time, for “Discovering Bitcoin Part 1: About Time.” Continue reading the “Discovering Bitcoin” series here: “Discovering Bitcoin Part 1: About Time” “Discovering Bitcoin Part 2: About People” “Discovering Bitcoin Part 3: Introducing Money” “Discovering Bitcoin Part 4: A Wrong Turn (New Plan Needed)!” “Discovering Bitcoin Part 5: Digital Scarcity” “Discovering Bitcoin Part 6: Digital Contracts” “Discovering Bitcoin Part 7: The Missing Pieces”

Discovering Bitcoin Part 1: About Time

As anticipated in the introduction to this series, we will start exploring the period of monetary (pseudo)history prior to fiat money, which we call “Plan A,” focusing on the topic of time and on the question “When?” There won’t be much cryptography or computer science in what follows: It will all sound very simple, even … primitive! Indeed, I would ask you, dear reader, to try to forget your advanced education and your civilized manners, and pretend, just for a few minutes, to be a fish-eating caveman. This is the first installment of bitcoiner Giacomo Zucco’s series “Discovering Bitcoin: A Brief Overview From Cavemen to the Lightning Network.” Read the Introduction to his series here.

From Immediate Consumption … to Storage …

Image courtesy of CryptoScamHub

Image courtesy of CryptoScamHub

Your caveman life is based on immediate consumption: You use your bare hands and a pointy stick to catch two fish every day, then you go back to the cave and you eat them immediately. One fish would be enough to survive, two are enough to feel “Thanksgiving full.” Every day you catch and eat two. You don’t save. It’s always the same. Your “utility function” (this is what a fancy economist would call it) is constant with respect to time.

Image courtesy of CryptoScamHub

Image courtesy of CryptoScamHub

But let’s try to think about the future for a bit! What if, instead of eating both fish, you eat just one and save the second (alive in a jar, for example)? Do it for two days in a row, and on the third day you will be able to eat your fill without even going out to fish! I will admit this is not a great improvement yet: You just give up some pleasure today and tomorrow, in order to get some rest on the third day. Not impressed.

… to Investment!

But what about spending that third day building a fishing rod (“capital good”), which would enable you to catch four fish instead of two, every day, forever? That’s called investment: You give up some pleasure for a while, but in return you get some productive and durable results. Congratulations, dear reader: You are a “low-time-preference capitalist caveman” now! With your brand new fishing rod, you can eat two fish every day and rest every two days!

But why stop here? You could invest some of your day off in building a large fishing net, which you could use to get eight fish a day! By saving and investing, you can get more fish, thus have more time to build something more efficient, as long as there are improvements to achieve. The more time you spend saving and investing, the wealthier you get. The growth is not even linear: Every improvement can build on top of the previous one! Soon enough, you will be “Captain Caveman”: commanding a huge fleet of wonderful fishing boats, getting 1,000 fish a day!

It’s easy to underestimate the deep implications of this process. Predisposition to invest (after having saved, delaying consumption) is linked to something economists call “low temporal preference,” which is, in turn, connected to very important effects on the well-being of people and of entire civilizations! A very good account of the significance of these topics and of their relationship with monetary technologies and practices is given in the book The Bitcoin Standard by Saifedean Ammous. Read it, if you haven’t. Another great reference is the essay “Money, Bitcoin and Time” by Robert Breedlove.

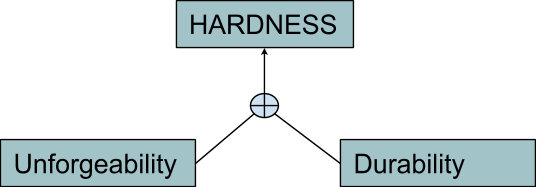

Physical “Hardness”

In order to be useful for this kind of process, a good must possess a good “hardness”: Any unit of said good should not significantly lose its ability to provide utility if stored over some period of time. (This means the good does not easily decompose, deteriorate or degrade, or it does so comparatively less than other goods.) Other common terms for this attribute are “durability” and “salability across time.” (In the context of your currently solitary condition, you should interpret the “sale” part as “you selling something to your future self.”) In all of the cases above, the expressions are often used beyond the physical scope to include the social and institutional attributes of goods as well. Since you are a lonely caveman, and there is no society or institution around you yet, we employ the term “hardness” only in the narrower sense of physical resistance to deterioration of the units of good, delegating other aspects to Part 3 (coming soon).

The good we chose as our first example, fish, is not very “hard,” comparatively, at least not if you don’t perform some specific actions as soon as you bring it back to your cave. A trivial action would be to keep it alive in a jar, as mentioned. Without additional treatments, a fish kept alive is more durable than a dead one. A smoked or salted fish, though, would be even more durable than one kept alive.

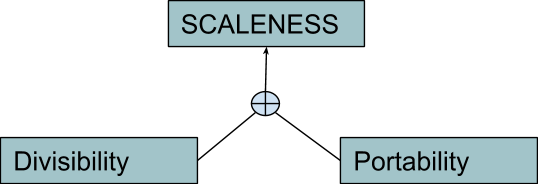

A New Attribute: “Scaleness”

Even dismissing social considerations, there is another reason for which unitary physical durability doesn’t really cover, alone, the broader concept of scalability across time. The fact is that the ability to store arbitrary quantities of a good is not dependant only on its unitary attributes! At the beginning of your virtuous cycle of saving and investment, you decided to eat one fish and to store the other alive. How convenient that, in order to survive, you needed to eat exactly one fish and not, for example, one and a half fish, leaving you with half a fish to store! Indeed, a live fish isn’t great for divisibility. Smoked, salted or refrigerated fish would fare way better. On the other hand, considering that by the time you appointed yourself “Captain Caveman” you started storing 1,000 fish every day, keeping them alive in jars must be quite challenging. Again: Conserved fish would be way easier to store than living specimens. In these examples, the discriminant is not how well any unit of good maintains its value across time, but rather how well the overall good maintains it across “scale”: when you store smaller fractions of it vs. when you store larger multiples. The former case is usually addressed in monetary theory with the term “divisibility,” the latter with the term “portability” (which often carries some movement-across-space connotations, but ultimately boils down to the fact that a portable good must possess high value in small bulk).

The composite attribute is sometimes called “salability across scale,” which, just like “salability across time,” is actually pretty neat. Since I like shorter terms, I will use the (almost made-up) word “scaleness” instead (I guess this is a case of terminology choice which would deserve a Trigger Warning as I described in my introduction). This attribute has more to do with the “What?” column than with the “When?” one, to be fair.

It’s interesting to note the nice link with the word “scalability,” which usually means something else entirely (it refers to the property of a system to handle a growing amount of work by means of additional resources). Within the context of Bitcoin, however, it has been used to address the technical limitations on the number of settlement transactions per unit of time and cost (related to the fact that blocks are limited in size and frequency). In this very specific meaning, the “salability problem” could be reduced to a divisibility one (basically, it doesn’t make economic sense to transfer amounts that are less valuable than the transfer costs), thus the conceptual link is justified. So far, you’ve learned:

- to store your wealth, sacrificing immediate consumption

- to invest your stored wealth, increasing your productivity

- to focus on goods that show good physical “hardness” and good “scaleness.”

But what can you do with all of the fish you catch every day? Not much, actually, if you are still able to consume just two and you can’t exchange them, which is something you will learn about tomorrow, in Part 2.

Discovering Bitcoin Part 2: About People

This is the second installment of bitcoiner Giacomo Zucco’s series “Discovering Bitcoin: A Brief Overview From Cavemen to the Lightning Network.” Read the Introduction to his series and Discovering Bitcoin Part 1: About Time. In this installment, we will build on the previously acquired strategies of storing wealth, investing that stored wealth, and increasing productivity and focusing on goods with physical “hardness” and good “scaleness,” to explore the concepts of exchange, specialization and “darkness.”

From Solitary Consumption … to Exchange …

Welcome back, dear reader. Let’s further explore the period of monetary (pseudo)history prior to fiat money, which we call “Plan A,” this time focusing on the topic of people and on the question “Who?” As we established in Part 1 you are now a very successful caveman: You own and manage a huge fleet of fishing boats, catching more fish than you could eat in a lifetime.

Image courtesy of CryptoScamHub

Image courtesy of CryptoScamHub

While you managed to leave immediate consumption behind, learning the art of saving and investing, you are still practicing solitary consumption. Not that you are necessarily alone: There might be someone around you, but you are not exchanging with anyone, so it doesn’t really matter if there is just one caveman or hundreds of cavemen (or cavewomen, or cave-nonbinary-people; you have to forgive the lack of politically correct sensibility in these articles — we are discussing primitive times). Every day, you catch 1,000 fish, eat two and store the rest. After a short while, your utility function gets flat with respect to the amount of fish you catch and the number of people around you. Consider this scenario: Apart from fishing, each caveperson can also draw two jars of water from the local spring every day and survive on drinking just one. What if, instead of eating two fish and storing 998, you start storing just 997 and exchanging one with Alice, a nice cavewoman who can give you an extra jar of water in return? In this way your utility increases, and after two days Alice could start working on her own fishing rod! Clearly, the number of possible exchanges can grow with the number of cavepeople in your local cave-economy.

Image courtesy of CryptoScamHub

Image courtesy of CryptoScamHub

But not that much, admittedly. First of all, it’s not all that hard for you to draw some water by yourself. Furthermore, Alice is also able to fish and save one fish per day, like you did: Why should she even exchange with you? Not impressed.

… to Specialization!

But why should every process of saving and investing deal with fish? The important insight is that you cavepeople are not all the same! You each have different skills, inclinations, beliefs, preferences, priorities and experience. Alice could become a great industrialist in the water sector, for example, producing tons and tons of jarred water a day. Bob, a talented cave-artist, could specialize in nice rock paintings! So, you suggest to your cave-friends that they should adopt this new, incredible strategy: specialization! Now everybody can focus on some specific skill, and every utility function can keep growing and growing, both with time and with the number of diverse people involved in the trade. This is what we call “division of labour”: the very cornerstone of civilization!

Specialization also improves investment and innovation, since even very simple tools needed for industry would be prohibitively hard to build without any help from people in other industries. (As you may know, even building just a pencil requires cooperation between thousands of different people from all over the world.) And many complex tools are needed, even just to create other tools! It’s a virtuous cycle: Specialization sparks innovation, encouraging cavepeople to invest time in creating tools (tool-making tools included), increasing productivity and freeing up more time, which in turn can be used to specialize even further or to reach an even greater number and variety of cavepeople to exchange with, thereby increasing the division of labor even further, and so on!

Hardness and Scaleness Strike Again

Of course, not every kind of good can be easily passed along many different hands. The main attributes that turned out to be useful to efficiently store some arbitrary quantity of a good also help to transfer it. A good with good physical hardness — which preserves its physical features at a unitary level when stored for a certain period of time — will typically also preserve the same features when transferred over a certain number of people, and vice versa. You would have a hard time naming a kind of good that is resistant to storage but not to transfer, or to transfer but not to storage. A good with good scaleness — which is efficiently stored in small fractions (divisibility) or in large aggregates (portability) — will also show the same features when passed from hand to hand instead of stored. What we are trying to express now is not exactly what economists would call “salability across space” (possibly redundant with the concept of portability); it’s actually closer to the concept of “salability across people.”

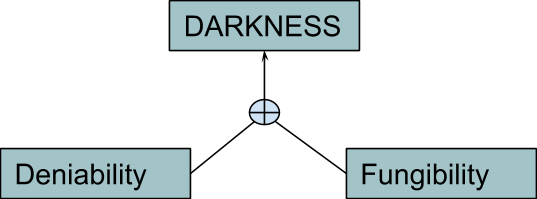

A New Attribute: “Darkness”

A good that’s durable enough to maintain its unitary physical properties over many exchanges, and with enough scaleness to be exchanged in huge multiples or in small fractions, is comparatively better, as far as salability across people is concerned. But these two attributes alone still don’t entirely cover that broader concept. You and your cave-friends want to exchange with a growing number of different people: the more different, the better, since diversity increases the chances of specialization. But diversity can also increase the chances of conflict and distrust: You know and like Alice and Bob, but you don’t really know, let alone like, all of these new people! You want to exchange goods that don’t carry the personal “mark” of previous owners and aren’t connected with a specific person or tribe; otherwise, it would be difficult for them to be accepted across large scopes of trade. Furthermore, the more people exchange, the more they draw the attention of caveman Mallory: a local bully who doesn’t want to increase his wealth by providing value, but by tracking, controlling, censoring and taxing exchanges. When Mallory’s lust for control arrives at the point that he tries to ban exchanges between cavemen not “registered” with him, a lot of cavepeople are excluded from the scope of trade: This is the phenomenon known as “financial exclusion” and it reduces utility for everybody.

Image courtesy of CryptoScamHub

Image courtesy of CryptoScamHub

Some goods are ideal for mitigating such problems — for example, “bearer instruments,” which don’t carry the personal information of previous owners, making it easy for everyone to deny having been involved in any specific transaction. When you deal with such goods, Mallory could at most ban you from the market because of who you are and what you are doing now (or not doing, such as not paying him a bribe), but not because of who the previous owners were (yourself included) and what they did. This isn’t an ideological problem, but a functional one: A good cannot easily be traded if the receiver has to verify the entire history of the previous owners in order to know how much political risk (including persecution, censorship, taxation, debt) he is actually inheriting. But it clearly involves moral, political and ethical aspects, like the importance of privacy as a human right. I will use the term “darkness” to address this attribute.

In the context of Bitcoin, many terms are used: privacy, anonymity and deniability (which focus on people more than on assets), but also untraceability and fungibility (which instead focus on the indistinguishability of asset units, but is, in turn, strictly connected with deniability, since a common way Bitcoin users could be spied upon is by leveraging a lack of fungibility of units, as we will see in detail in Part 6).

So far, we’ve learned:

- how to exchange your wealth, giving up your solitary lifestyle for a cooperative one;

- how to specialize in the production of something specific, advising your trade partners to do the same; and

- how to focus on goods that show good “hardness” and “scaleness,” but also good “darkness.”

But how can you exchange with a growing number of people if the complexity of all the different combinations of goods, from the demand and the supply points of view, grows even faster? This is something you will discover in “Discovering Bitcoin Part 3: Introducing Money.”

Discovering Bitcoin Part 3: Introducing Money

This is the third installment of bitcoiner Giacomo Zucco’s series “Discovering Bitcoin: A Brief Overview From Cavemen to the Lightning Network.” Read the Introduction to his series, Discovering Bitcoin Part 1: About Time and Discovering Bitcoin Part 2: About People. In this installment of the “Discovering Bitcoin” series, we will build on the previously acquired strategies of exchanging wealth, specializing production and focusing on goods with good physical “hardness,” “scaleness” and “darkness” to explore concepts of scarcity, liquidity and social “hardness.”

From Barter … to Liquidity Maximization …

This third step along our “Plan A” for money will focus on the topic of scarcity and on the question “What?” In Part 2, you invented and popularized practices such exchange and specialization, enabling an unprecedented level of wealth and cooperation. Good job! There is still a problem, though. In the context of barter, which is what you and your fellow cavepeople are practicing now, utility grows with the number of people exchanging, but the friction to match demand and supply for every good versus any other grows as well, since the number of all the possible combinations increases quickly! This problem has two sides: one concerns how to calculate, communicate and keep track of all of the combinations of trading couples (each caveman must declare how much of everything he would accept in exchange for everything else). The other concerns liquidity within different pairs (in many scenarios the exchange simply cannot happen, because of what economists call “non-coincidence of wants”: Alice has something Bob wants, but not the other way around, or at least not in that moment). The former side can be mitigated with advancements in information technologies (such as the invention of writing, to keep track of different combinations), while the latter can be mitigated by delaying the actual delivery of one of the two exchanged goods (basically the invention of credit, which is very useful where the wants do not coincide if considered in real time, but would instead coincide in different time-frames). But the problem still exists, slowing down the specialization process.

… to Convergence!

In order for commerce to keep growing, your little cave-economy must converge toward some specific kind of good, namely the one with the best combination of monetary attributes, which will always represent one side of every trade, in order to simplify calculation and bridge liquidity with respect to every other good. This practice is known as indirect exchange: Alice trades what she offers for this “bridge-good,” which she will later trade again for something she wants. The great news is that you don’t have to try to convince your cave-friends one by one. This switch naturally happens due to so-called “network effects”: The value of a network increases more than linearly with the number of participants, creating a kind of gravitational black-hole effect. The goods that fare better in hardness, scaleness and darkness will compete, and the first one to reach a critical mass will start swallowing the others, as far as monetary uses are concerned.

Cave-ladies and cave-gentlemen … introducing Money! It serves three functions. The first is “store of value,” which was actually already served by our stored goods within the context of pre-convergence barter economies. The others are “unit of account” and “medium of exchange,” which are the answers to the problems of pricing and liquidity, respectively. This is an important step in human evolution, so much so that from now on I will stop addressing you and all of your friends, as “cave-somethings.” With the level of prosperity that money-based economies give you over barter-based ones, you can all get out of those smelly caves and enjoy stone houses and castles!

How to Get Good Money

So, you just entered the magical world of so-called “commodity money”! Historical examples are seashells, beads, spices, squirrel pelts, dolphin teeth, tea bricks, salt (the word “salary” comes from that) and sheep (the word “pecuniary” from that). But now you have to face another challenge, once again related to the problem of salability across time (thus back to the “When?” question)! Imagine you’ve convinced your tribe to use smoked fish as money. This created more demand than the one granted by food consumption alone: Not only do people want to eat it, but they now also want to use it as money. Its price shows what is called a “monetary premium.” This incentivizes you to restructure your enterprise in order to produce more of it — but then you increase the global smoked-fish supply. And the price is a result of demand and supply: If the latter keeps increasing, while the former doesn’t, the price will start falling. So, even if smoked fish remains as durable as before in a physical sense, it will perform poorly as a way to store value across time. Price dynamics affect hardness in a “social” way: In the context of solitary consumption, the good would still maintain its ability to provide utility over time, but in the more advanced context of a monetary economy, that ability actually drops. And a lousy store of value cannot be a good medium of exchange, since nobody wants to lose value storing it for indirect exchange! This is not just a smoked-fish thing. It’s very general: The more any good gets used as money, the more interesting it becomes for its typical producers to increase the supply in order to profit. The more the supply increases, the less that good can be used as money. This cycle isn’t a smooth and gradual negative-feedback loop that tends toward equilibrium over time — the changes to the production structure in order to increase the supply take some time to be done and aren’t easily undone after the value decreases! The typical outcome is more of a “boom and bust” kind. There are many historical examples of this “money trap,” usually involving disastrous outcomes. This is typical of goods with a low “stock to flow” ratio, where even small percentages of change in the flow (amount of good produced or extracted in a unit of time) are comparatively huge, and thus particularly disruptive, with respect to the stock (amount already circulating in the economy).

Social “Hardness”

You soon realize that seashells trapped on your fishing nets, which you used to collect, provide a better money than your deliciously useful smoked fish, in this regard. And that those relatively “useless” gold nuggets you used to collect on the shelf next to seashells are even better!

Image courtesy of CryptoScamHub

Image courtesy of CryptoScamHub

Actually, you probably want to use both gold and silver. The reason is that they perform better on different sides of the scaleness spectrum: While gold is more portable, silver is more divisible. Indeed, commodities that possess a consumption value higher than their monetary premium are not very good candidates for monetary use: Since they get consumed, their stock tends to diminish, lowering their stock-to-flow ratio. In this sense, “commodity money” is more an evolution of collectibles than of actual industrial commodities. Different terms are used to address the attribute of having a supply that tends to remain inelastic with respect to increases in the demand, keeping its value over time. Various sources call it “soundess,” “unforgeable costliness” or “unforgeability.” I will extend the word “hardness,” which we already used for the physical side of the durability problem, equating it with the more general concept of salability across time, in a physical and social sense as well.

This is a jump back to the “When?” column, to complete our analysis of the relation between time and value: The higher the degree of hardness of some monetary good, the more resistant it is to having its value compromised, either by physical decay or by supply inflation.

The question of hardness influences the process of monetary convergence: Any monetary good that can have its supply cheaply and easily increased will rapidly destroy the wealth of those using it as a store of value. For a good to assume a dominant monetary role within an economy, it must exhibit superior hardness to competing monetary goods. When discussing hardness, purely economic considerations overlap with ideological, political and ethical ones, just like with darkness. As noted in Part 1, they mostly have to do with the notion of time preference, a topic with deep ramifications in sociology, but they also relate to the problem of inflation as a way to transfer wealth, and the problem of interest-rate manipulation as a cause of financial crises. So far, you’ve learned:

- to advise your trade partners to converge over a single good to maximize liquidity;

- to choose that good among the ones with a better mix of physical “hardness,” “scaleness” and “darkness”; and

- to consider the social, supply-related aspect of “hardness,” along with the physical one.

In a word, you’ve basically discovered money. But can you make it better? This is something you will discover in “Discovering Bitcoin Part 4: A Wrong Turn (New Plan Needed)!”

Discovering Bitcoin Part 4: A Wrong Turn (New Plan Needed)!

This is the fourth installment of bitcoiner Giacomo Zucco’s series “Discovering Bitcoin: A Brief Overview From Cavemen to the Lightning Network.” Read the Introduction to his series, Discovering Bitcoin Part 1: About Time, Discovering Bitcoin Part 2: About People and Discovering Bitcoin Part 3: Introducing Money. In this next installment of the “Discovering Bitcoin” series, we will build on the previously acquired strategies of optimizing “hardness,” “scaleness” and “darkness” to explore concepts of virtualization and decentralization.

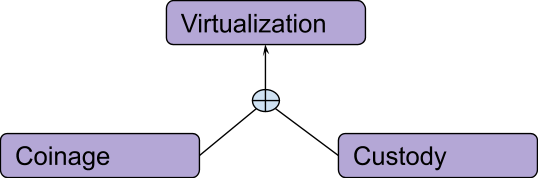

The Path Toward Virtualization

The question “Where?” will bring us to the (quite unhappy) end of Plan A and the beginning of Plan ₿! Thanks to your noble efforts, everybody is now using gold and silver as money. (With such a track record, you decide monetary innovation is your actual vocation: You sell your fishing fleet to focus on that exclusively.) The next innovation you introduce is “coinage.” While people used to sustain important verification costs when receiving metal money, now you can pre-sign standard measures (obviously you ask for a fee for such a service, called “seigniorage”), and everybody can just cheaply verify your signature.

Image courtesy of CryptoScamHub

Image courtesy of CryptoScamHub

Coinage (which is particularly interesting for Bitcoin, since it’s similar to the dangerous practice known as “SPV,” which we will discuss later in Part 7) increases hardness locally, since lower verification costs mean higher forgery costs for occasional counterfeiters. But while it may increase locally, hardness may also decrease globally: Now you have the ability to inflate the money supply with a trick called “debasement” (just put less gold in your coins than you originally promised, secretly increasing your seigniorage fee). Next, you invent “custody”: Instead of securing their coins directly, people can entrust them to you, in exchange for convertible certificates. Since you leverage economies of scale and specialization, you’ve become quite efficient at securing other people’s money (for a fee, of course).

Image courtesy of CryptoScamHub

Image courtesy of CryptoScamHub

Custody increases scaleness dramatically! So much so that it helps the convergence process to reach its ultimate completion: Having to store just paper instead of physical gold (not very divisible) and physical silver (not very portable), people converge over the former (harder money), demonetizing the latter (the monetary premium of which will eventually collapse). But global darkness and hardness may instead decrease: In the redeeming phase, you could easily track and censor transactions, or you may practice what is called “fractional reserve” (keeping less collateral than issued certificates, basically inflating the “virtual” supply).

Complete Virtualization

Your next proposal is complete virtualization. (Funny note: Bitcoin is often called “virtual money,” but money has already been “virtual” for centuries!) It’s the merging of custody and coinage: Instead of just entrusting you with some signed coins in order to redeem them later themselves, people can start trading your signed paper certificates directly, using them as a medium of exchange. You finally invented “banknotes”!

It’s not commodity money anymore; it’s some kind of “information money” (not yet what we call “fiat money,” though — it’s still a form of free-market innovation, emerged from society without any kind of legal imposition, provided by different competing actors and collateralized with physical gold in custody). Sure, you could abuse censorship, debasement and fractional reserve, if you wanted, but you aren’t Mallory (our bully from Part 3); you’re a reputable professional, and these bad incentives are mitigated by the competitive pressure of several other providers.

We could consider the process of virtualization as an extreme case of specialization (after money enabled division of labor, money management itself become a specialized job itself). It’s a centralizing process: Collateral physically moves from many users to the few service providers.

Ultimately, the “Where?” question isn’t really geographical in nature: It’s more about control. The provider may have vaults, or mints, distributed across the world, but their control is centralized.

A Wrong Turn: Monopoly

You haven’t forgotten about Mallory the bully, right? Good, because he is the main character in the transformation from free-market virtual money to fiat money! For a while he posed as a mere competitor to your services of custody and coinage, but now he is revealing his true colors. While it was pretty difficult for him to take over the very decentralized process of people exchanging gold nuggets, there are now a few big, public, trusted, vulnerable entities he can easily seize control of. First, he uses threats of physical violence to establish a compulsory monopoly on virtual money (or even on money tout court, regardless of whether or not the physical variant is out of fashion anyway by now), ruling all the alternative money services, including yours, “illegal.” Then he forces everyone to always accept his particular brand of virtual money as payment at face value. (He likes to call this obligation “legal-tender laws.”) Finally, he abolishes any kind of redeemability of his certificates in actual gold collateral. Now the supply of money is politically defined (by Mallory-appointed central bankers, who can finally implement “monetary policies” to shape the economy based on his political goals), while the demand for money is politically driven (since people are forced to own the legal tender to pay taxes to Mallory, and are forced to accept it at nominal value when they trade).

Image courtesy of CryptoScamHub

Image courtesy of CryptoScamHub

Until now, in the context of free-market virtual money, competition and market forces could have somehow still incentivized banknote issuers to “behave.” With fiat money, thanks to legal monopoly and legal-tender laws, there’s no competition anymore, at least not within the context of Mallory’s “jurisdiction.” (There are other, smaller Mallories around the world, but they all joined the Big Mallory in a huge cartel).

The Internet and Digitalization

Enter the digital era! With e-commerce, people need to transact over the internet, but they can’t exchange paper there. Mallory’s fiat money (which is already virtual) migrates to digital versions that are orders of magnitude more efficient: Scaleness increases again! Somebody could argue that in leveraging digital technologies, scaleness would have gone up even more in the competitive context of digital free-market money (since a monopoly keeps costs high while keeping efficiency, transparency and innovation rates low). But since things are improving anyway, nobody complains too much. But hardness and darkness decrease dramatically: The money supply can be manipulated to degrees never seen before, and Mallory can track and censor transactions to Orwellian extents.

Image courtesy of CryptoScamHub

Image courtesy of CryptoScamHub

As a money entrepreneur, you try to leverage the same innovations that made Mallory’s money so powerful in order to bring back free-market representative money, only this time “on digital steroids.” Your hope is that the very same internet that Mallory leveraged to increase his power could also be leveraged by you to bypass, ignore and circumvent Mallory’s impositions. You launch a startup called “e-gold” (this is all completely fictional, of course). Your service allows pseudonymous users to open accounts denominated in grams of physical gold, freely transacting among them. You set it up using technological best practices and you devise innovative governance structures. After some time, your system has grown to 5 million accounts, processing the equivalent of 2 billion Mallory-dollars per year! But despite your great execution and the positive market reception, all of your technical and legal skills cannot protect you from Mallory’s violence forever. Eventually, he manages to shut your business down and send you to jail, discouraging other entrepreneurs from following your example. (They pivot to some traditional, Mallory-approved, digital fiat services instead.)

Image courtesy of CryptoScamHub

Image courtesy of CryptoScamHub

Decentralization: A New Hope?

During the time you “serve” in jail as a retribution for daring to try to provide better money than Mallory’s, you realize something: It was very easy for Mallory to send you to jail, close your company and shut down its servers, because the personal, legal and technical structures were all easy targets. What if, this time, you replace your official identity with some internet pseudonym (the Japanese-sounding “Satoshi” may be just as good a choice as any), your for-profit company with an open FLOSS project, and your server with a peer-to-peer protocol? Then Mallory would have no CEO to incarcerate, no legal entity to seize, no server to shut down! The idea is to reverse the centralization trend that has prevailed until now, while retaining most of the advantages of technological progress that enabled e-commerce and e-finance.

So far, you’ve learned:

- that the process of money virtualization greatly increases its “scaleness”;

- that the same process enables violent monopolies, which in turn greatly decrease “hardness” and “darkness,” especially in the digital era; and

- that you cannot effectively fight monopolization using centralized entities. You have to aim for decentralized solutions.

But how can you actually decentralize asset issuance and ownership? We will answer the first of these two questions in “Discovering Bitcoin Part 5: Digital Scarcity.”

Discovering Bitcoin Part 5: Digital Scarcity

This is the fifth installment of bitcoiner Giacomo Zucco’s series “Discovering Bitcoin: A Brief Overview From Cavemen to the Lightning Network.” Read the Introduction to his series, Discovering Bitcoin Part 1: About Time, Discovering Bitcoin Part 2: About People, Discovering Bitcoin Part 3: Introducing Money and Discovering Bitcoin Part 4: A Wrong Turn (New Plan Needed)! Next in the “Discovering Bitcoin” series, we will build on the previous events of money virtualization, establishment of dangerous monopolies and emergent needs for decentralization, to explore concepts of scarcity in the “virtual” world, energy consumption and digital hardness.

Proving Work: Digital Puzzles

Welcome back to this journey through our Plan ₿ for money, which brings us, for the second time, to focus on the topic of scarcity and the question “What?” Value needs scarcity, but in the digital world that’s really difficult to get: Information tends to always be infinitely reproducible. In your previous e-gold experiment, digital units represented actual physical gold stored by your centralized company. But how can you create a protocol in which everybody can independently agree on what is being transmitted, without any central authority? If such a method required a centralized third party, you would be back where you started, with a central point of failure vulnerable to Mallory. If such a method was “everybody can issue however many units they want,” the system couldn’t work: Incentives would push the supply of units toward infinity, and their price toward zero. The answer you finally come up with is puzzles! You write an open procedure that everybody can run on their computers in order to try to solve some puzzles with the characteristics of being “ad hoc” (specifically built around every issuance attempt, otherwise solutions could be reused many times), asymmetric (difficult to solve but easy to verify, otherwise the system would be vulnerable to denial-of-service attacks) and “useless” (otherwise external use cases for the same solution effort could distort incentives within the system). Every solution will grant the “right” to issue a certain number of units.

Image courtesy of CryptoScamHub

Image courtesy of CryptoScamHub

Non-digital examples of similar puzzles are sudokus or crosswords: “useless” games in which finding the solution (which depends on some specific parameters that are different every time) requires a lot of trial and error, while verifying that solution, once it has been found, is trivial and quick. More technically, what you need is called “proof of work” (PoW). It’s somewhat similar to a CAPTCHA, but intended for computers and not humans to solve.

Hashcash

Your choice falls on a specific kind of PoW called “Hashcash” (created by your friend Adam and originally intended for spam prevention in the context of anonymous email exchanges). The way it works is through “hash collision”: a kind of “brute force attack” where a machine automatically tries out several slightly altered versions of the original message, over and over, with little changes every time, until one of the versions, passed through a one-way function called a “hash” (the mathematical equivalent of fingerprints or footprints), results in a string that respects some kind of constraint. Hash functions, while deterministic (starting from the same message, they give the same result every time), are also unpredictable (slightly different messages will result in completely different hashes, in a way impossible to guess or predict before actually calculating them) and irreversible (it’s easy for everybody to verify the hash of a known message, but it is not possible to go back to a single message from just a hash). If your users want to “deposit” digital assets, they have to create a “deposit” transaction, add some random number and apply a hash function, repeating the process over and over again until the result, for some number, is verifiably smaller than a certain threshold, called “difficulty.”

Energy Consumption

Your users will have to “waste” some energy to find solutions, but this is a requirement, not a bug: The only way to make something scarce is to make it costly to produce — there’s no other way around it. This “waste” argument is often used by critics of your system (especially Mallory and his friends) to accuse your pseudonymous alter ego of being “environmentally unfriendly.” This is not really the case, for several reasons. First, energy spent in PoW is no more “wasted” than in any other production process for any other (physical or intellectual) good. Second, the consumption of energy in your system is likely going to remain lower than historical alternatives (we are talking orders of magnitude less than the energy consumption for gold extraction, for example). Third, entrepreneurs generating PoW to get some “digital gold” aren’t incentivized to consume more energy — if anything, they are incentivized to consume less of it (to them it’s a cost, not a revenue). This drive toward using less energy increases optimization and efficiency with new technological breakthroughs or with smart generation choices, which in turn can have a waterfall effect on other energy-consuming industries. There would be no advantage to complicated kinds of PoW that make optimizations difficult. Indeed, the opposite is true: The most efficient PoW is one that is friendly to optimizations (the ideal being a process close to the thermodynamic limit).

Hardness Problems

Now, anyone in the network can verify that a certain amount of computational work has been uniquely “committed” to a certain asset deposit, but no one can reproduce that same proof for other types of statements. But this proof of work by itself is not enough to give your “digital gold” any hardness. It doesn’t guarantee that the supply will remain inelastic with respect to the demand. The hashcash model would actually be, in and of itself, very inflationary: The more the demand for your “digital gold” increases, driving the price up, the more machine power will be deployed to perform PoW, and the more resources will be invested to increase energetic efficiency, thus increasing the supply, if the latter is not additionally restricted.

The next innovation you need to include in your system is called “controlled supply.”

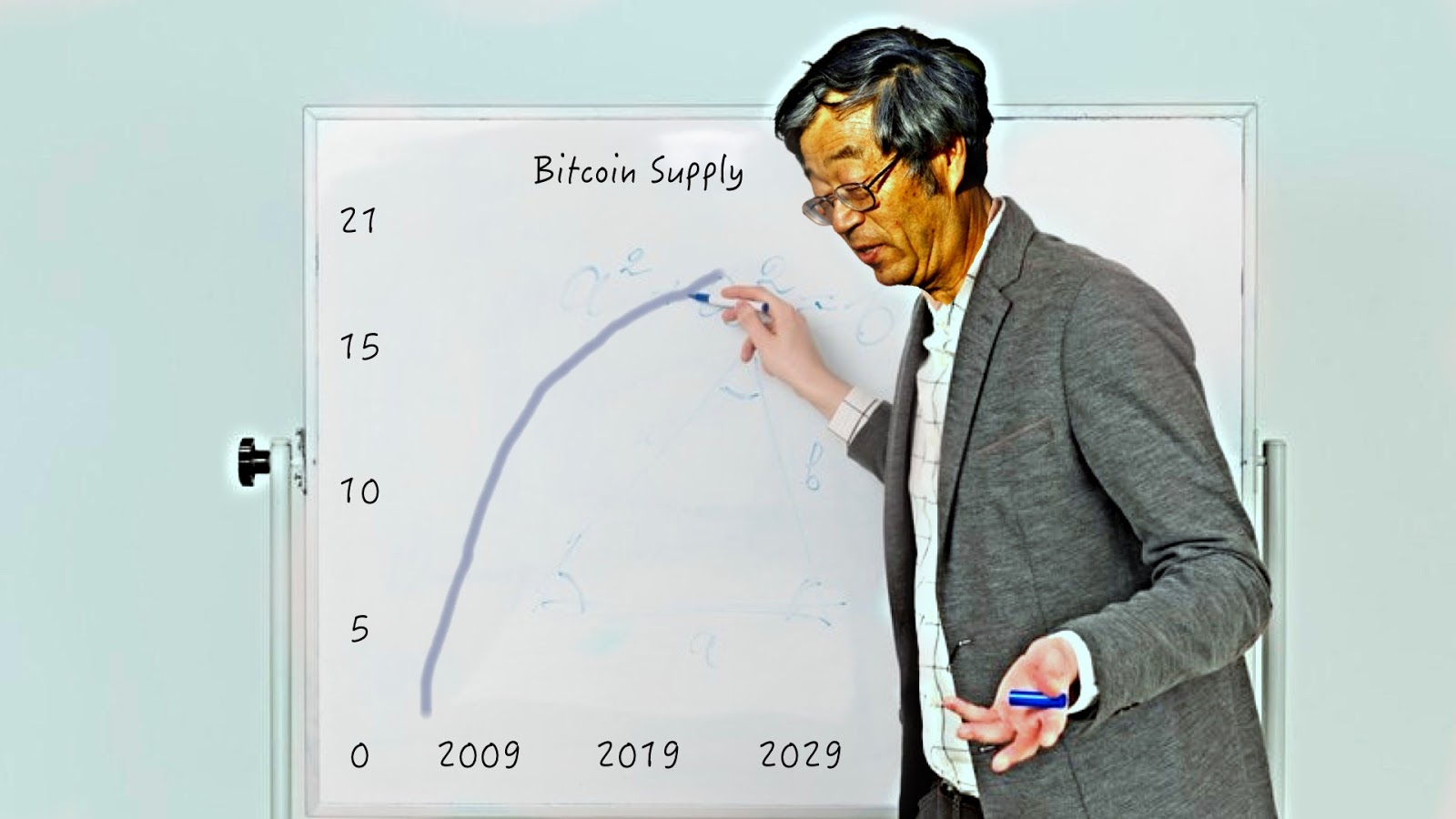

A New Paradigm: “Controlled Supply”

Basically, whenever the issuance rate is above (or below) a certain target, the puzzle difficulty increases (or decreases), balancing the rate. You set a target of one “issuance,” on average, every 10 minutes, as measured every 2,016 “issuances” (which means about every two weeks). This makes for an almost perfectly constant issuance rate. Actually, you just launched the very first asset in history with an almost totally inelastic supply compared to the demand. Whenever the monetary demand for your “digital gold” increases, the price increases, incentives to perform PoW increases and the issuance rate starts increasing as well, but then the difficulty increases and the supply goes back to being stable again — and the other way around, of course, in case the demand goes down. But you decide to go even further. Instead of having just a fixed schedule, you aim for a fixed total supply and introduce the “halving” mechanism: At the end of every “era” of about four years, the issuance rate is cut in half, eventually approaching a fixed stock with zero flow! The first era starts with a maximum issuance of 5 billion virtual “units,” which the users call “satoshis” or “sats,” as a tribute to the pseudonymous alias you came up with in Part 4. In the second era, only 2.5 billion sats will be deposited every 10 minutes, on average. In the third era, that number will go down to 1.25 billion, and so on. You chose this model to approximate the way a physical gold mine would become exhausted over time, and you call it “mining” to emphasize the analogy.

Image courtesy of CryptoScamHub

Image courtesy of CryptoScamHub

When you were using a centralized approach, you could simply piggyback the (relatively) stable price of physical gold. This new “digital gold” will require, instead, a long, difficult and volatile process of price discovery. The disinflationary nature of the issuance schedule could make some phases of this process even more “violent.”

So far, you’ve learned:

- that in order to launch a completely decentralized system, you cannot leverage physical scarcity;

- that you can reproduce scarcity digitally and decentralize issuance, using special digital puzzles; and

- that in order to grant some hardness to your digital money, you need a strict supply control.

But now that you have effectively decentralized issuance, how can you do the same for ownership? We will answer that in “Discovering Bitcoin Part 6: Digital Contracts.”

Discovering Bitcoin Part 6: Digital Contracts

This is the sixth installment of bitcoiner Giacomo Zucco’s series “Discovering Bitcoin: A Brief Overview From Cavemen to the Lightning Network.” Read the Introduction to his series, Discovering Bitcoin Part 1: About Time, Discovering Bitcoin Part 2: About People, Discovering Bitcoin Part 3: Introducing Money, Discovering Bitcoin Part 4: A Wrong Turn (New Plan Needed)! and Discovering Bitcoin Part 5: Digital Scarcity. In Part 6 of this “Discovering Bitcoin” series, we will build on the idea of using digital puzzles as a way to reproduce scarcity, and on the importance of a supply-control mechanism to grant some hardness to digital money, to explore concepts of proving ownership through signatures and scripts, and the technique known as CoinJoin.

Proving Ownership: Signatures

Our Plan ₿ for money brings us, for the second time, to focus on the topic of people and the question “Who?” You established the conditions for the issuance of new sats, but what about their transfer? Who is authorized to change the data in the shared balance sheet, transferring ownership? If there was a central authority in charge of reassigning sats, following instructions by current owners (maybe logged in to the system with the classical username-and-password approach, like in your previous e-gold experiment), there would be a Mallory-vulnerable single point of failure again: Why then even bother moving from physical gold to PoW-based “digital scarcity”? If, on the other hand, each user had an equal right to reassign ownership, then your system could not work at all: Everybody would be encouraged to continuously assign other people’s sats to themselves. You need some kind of consistent authority-defining protocol, which everybody could independently check. The solution is a cryptographic technique called a “digital signature.” It works like this: First, Alice chooses a random number called a “private key,” which she will keep absolutely secret. Then, she passes this number through a special mathematical function, easy to apply in one direction but practically impossible to reverse. The result is another number called a “public key,” which Alice doesn’t keep secret at all: Instead, she makes sure that Bob gets to know it. Finally, she passes the private key and the message through a second function, again difficult to reverse, which results in a very big number called a “signature.” A third and last mathematical function can be applied by Bob to the message, the signature and Alice’s public key, resulting in a positive or negative verification. If the result is positive, he can be sure that Alice authorized that message (“authentication”), that she will not be able to later deny that authorization (“non-repudiation”) and that the message was not altered in transit (“integrity”).

In a way, it’s similar to handwritten signatures (thus the name), which are easy for everybody to check against some public sample, but difficult to reproduce without being the owner of the “correct hand.” Or to wax seals: easy for everybody to check against a public seal registry, but difficult to reproduce without the correct wax stencil. So, you change your protocol in order to make fractions of proofs of work independently reusable via digital signatures. The first model you implement is trivial: Each user independently generates a private key and creates a public “account,” labeled with the corresponding public key. When users want to transfer ownership, they create a message including their account, the receiving account and the amount of sats they want to transfer. Then, they digitally sign and broadcast the message, which everybody can verify. Interestingly enough, a similar scheme can be used by many renowned (yet possibly pseudonymous) developers to sign different versions of your software so that they can freely change, improve, fix, update, audit and review it, and any final user of your system can independently verify said signatures before running their preferred version, leveraging a network of minimized and fragmented trust, without a need for a single authority to centrally distribute the software. This process enables a true decentralization of code.

Script and “Smart Contracts”

You don’t want to limit the conditions that every peer has to check, before accepting any change in the shared balance sheet, to mere digital-signature validity, though. You decide that each message can also include a “script”: a list of instructions describing additional conditions that the receiving account (or accounts) will have to satisfy in order to spend again. For example, the sender could require a combination of several secret keys (in conjunction or disjunction) or a specific waiting time before spending. Starting from these very simple (and easy to audit) primitives, complex “smart contracts” can be built, making money effectively “programmable,” even in the absence of central parties.

Darkness (and Scaleness) Problems

Unlike an encrypted messaging system (where if Alice sends Bob some messages, only Bob can read them), your scheme isn’t really optimized for darkness (if Alice sends Bob sats, her message will have to be revealed beyond Bob — at the very least to those who will receive those same sats later on). Money circulates. Payees cannot trust any money transfer, even if properly signed, if they cannot verify that the transferred sats have actually been transferred themselves to that specific payer, and so on, upstream, back to the very first PoW-based issuance. With enough circulation of sats, active peers would get to know a huge number of past transactions, and forensic analysis techniques could be employed to statistically correlate amounts, timings, metadata and accounts, thereby deanonymizing many users and stripping them of their deniability. This is problematic: As discussed in Part 2, darkness is a fundamental quality for money, both for economical and sociological reasons. Smart contracts make this problem even worse, since particular spending conditions may be used to identify particular software implementations or specific organization policies. This lack of darkness is more serious than the one that affected your previous e-gold experiment: It’s true that, back then, you stored most transaction metadata on your central servers, but at least it was only you, as opposed to quite literally anybody (including many of Mallory’s agents), who had access! Furthermore, you could implement some particularly advanced cryptographic strategy to make yourself at least partially “blind” to what was actually going on between your users. There’s also a minor scaleness problem connected with this design: Digital signatures are quite big, and the chain of transfers that a payee needs to receive in order to validate everything would include many signatures, making validation potentially more expensive. Furthermore, account changes are quite difficult to validate in parallel.

A New Paradigm: “CoinJoin”

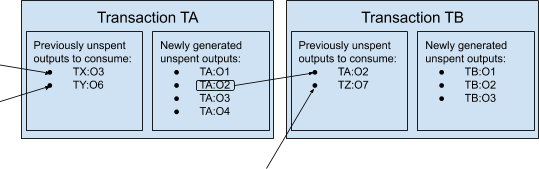

To mitigate such problems, you decide to change the fundamental entities of your model from bank-like “accounts” to “Unspent Transaction Outputs” (UTXOs). Instead of instructions to move sats from one account to another, each message now includes a list of old UTXOs, coming from past transactions and “consumed” as ingredients, and a list of new UTXOs, “generated” as products and ready for future transactions. Instead of publishing a single, static public key to be used as general account reference (like a bank IBAN or an email address), Bob must provide new, single-use public keys for each payment he wants to receive. When Alice pays him, she signs a message that “unlocks” some sats from some previously created UTXO, and “locks” them again into some new UTXO.

Just like with physical cash, spendable bills don’t always match payment requests — change is often required. If, for example, Alice wants to pay 1,000 sats to Bob, but she only controls several UTXOs locking 700 sats each, she will sign a transaction consuming two of those 700-sats UTXOs (unlocking a total amount of 1,400 sats) and generating two new UTXOs: one associated with Bob’s keys, locking the payment (1,000 sats), and the other associated with Alice’s keys, locking the change (400 sats). Provided that people don’t reuse keys for different payments, this design increases darkness in and of itself. But even more so when your users start to realize that UTXOs consumed and generated by a single transaction don’t have to come from just two entities! Alice can create a message spending old UTXOs she controls and generating new UTXOs (associated with Bob), then she can pass said message to Carol, who can simply add her old UTXOs she wants to consume and the new UTXOs (associated with Daniel) she wants to create. Finally, Alice and Carol both sign and broadcast the composite message (paying both Bob and Daniel). This special use of the UTXO model is called “CoinJoin.” (Trigger warning: Within the actual Bitcoin history, this use wasn’t Satoshi’s design rationale for the UTXO model itself, but was discovered as a potential twist on said design by other developers, many years after the launch.) It breaks the statistical linkability between outputs, while preserving what is called “atomicity”: Transactions are either entirely valid or invalid, thus Alice and Carol don’t have to trust each other. (If one of them tries to alter a partially signed message before adding their own signature, the existent signature becomes invalid.)

There is a possible change to your system that may actually improve the situation even more: a different digital-signature scheme, alternative to the one you’re using now, which is “linear in the signatures.” That means: In taking two private keys (which are nothing but two numbers), signing the same message with each and adding together the resulting signatures (which also are nothing but two very big numbers), the result happens to be the correct signature corresponding to the sum of the two public keys associated with the two initial private keys! This sounds convoluted, but the implication is simple: Alice and Carol, when CoinJoining, could add up their individual signatures and broadcast just the sum, which everybody could verify against the sum of their public keys! Since, as we said, signatures are the “heaviest” part of transactions, the possibility of broadcasting just one instead of many would save up a lot of resources. External observers would end up suspecting every transaction of being a CoinJoin, since many users could be after efficiency gains. This assumption would break most of the forensic heuristics.

Image courtesy of CryptoScamHub

Image courtesy of CryptoScamHub

Even without this further improvement, the UTXO model already somehow increases scaleness: Unlike state changes in the account model, it allows validation to be efficiently batched and parallelized.

So far, you’ve learned:

- that you can decentralize ownership using digital signatures for transfer;

- that you can turn transactions into programmable “contracts” with a script system; and

- that a more complex paradigm called CoinJoin can further increase darkness and scaleness.

But now that your users can issue sats and transfer them in a completely decentralized way, how can they all be sure that a single chronology is followed, preventing double-spending attacks or attempts to tinker with the inflation schedule? We will answer that in our final installment, “Discovering Bitcoin Part 7: The Missing Pieces.”

Discovering Bitcoin Part 7: The Missing Pieces

This is the seventh and final installment of bitcoiner Giacomo Zucco’s series “Discovering Bitcoin: A Brief Overview From Cavemen to the Lightning Network.” Read the Introduction to his series, Discovering Bitcoin Part 1: About Time, Discovering Bitcoin Part 2: About People, Discovering Bitcoin Part 3: Introducing Money, Discovering Bitcoin Part 4: A Wrong Turn (New Plan Needed)!, Discovering Bitcoin Part 5: Digital Scarcity and Discovering Bitcoin Part 6: Digital Contracts. As we conclude our “Discovering Bitcoin” series, we will build on the use of digital signatures and of the CoinJoin paradigm to explore concepts of unique chronology, mining fees and off-chain transactions.

Proving Unicity: Timechain

We are finally at the end of our exploration of Plan ₿, back again to the question “When?” from whence we started. It’s an important question, as it justifies the introduction of the so-called “blockchain technology,” a decidedly abused expression that, in its original meaning, just labeled the answer to a problem of unique chronology. (It’s interesting, in this regard, that Satoshi himself called this structure “timechain,” which is also the term we are going to use here … sorry, Peter!).

Let’s try to understand what problem it solves, by getting back to our little story. You designed a digital cash system in which issuance and ownership are both decentralized, leveraging puzzles and signatures in a clever combination. But how do you prevent users from double-spending the same UTXO? If Carol, a dishonest user, transfers sats to an address controlled by Daniel, and then signs another transaction that retransmits those very same sats to an address controlled by herself, which transaction will the network enforce? They would both be “valid” from the point of view of the chain of signatures and scripts, and both would point to a valid initial issuance, with a correct PoW difficulty. And how do you prevent “miners” from lying about the correct timestamp, tricking the difficulty adjustment algorithm to increase the issuance rate? If the miner Minnie manages to solve hundreds of PoW puzzles at low difficulty, but she includes forged timestamps that depict the solutions as only 10 minutes apart from each other, how can a generic user, maybe just recently connected to the system, discover and prove such dishonest behavior? Within your previous e-gold experiment, your trusted timestamp server trivially solved both issues. But now there is no central server, so who defines the unique chronology of events? If the network could somehow “vote,” it could reach a “democratic” consensus about it. But voting processes, while feasible in systems with a fixed number of known actors (often called “federations”), can’t work within dynamic sets of unknown, anonymous actors. You can’t simply use “node count” as a proxy for voting rights, since every user could pretend to “be” millions of different nodes in what is known as a “Sybil attack.” You need another, “Sybil-resistant” way to push all the nodes to find (and keep) consensus over one single, consistent, immutable history.

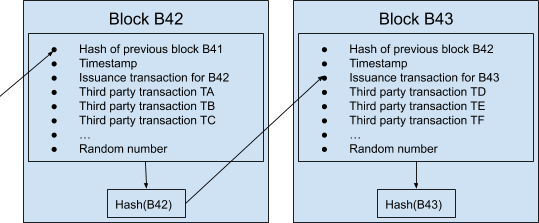

Unfortunately, a deterministic and final solution based on mathematics is theoretically impossible. But a statistical and asymptotic solution based on economics is practically possible, and you are smart enough to find it. This is the idea: Every time miners try to solve PoW puzzles, they should include in their messages compact snapshots of the current transactional timeline! Instead of just their issuance messages, they should pass through the hash function more complex “blocks” of information, each containing (along with said issuance message, a timestamp and a random number needed to solve the puzzle at the correct difficulty) the solution of the previous block (which had been found by other miners about 10 minutes before) and a list of transactions recently made by other users.

A block that contains transactions already included in previous blocks is considered invalid. A block carrying a timestamp that is significantly incompatible with the previous ones is also discharged. Using this trick, all actors are incentivized to converge on a consistent version of the same chronology. Minnie could include a valid transaction contradicting (double-spending) a previously confirmed one, or alter the timestamp to trick the difficulty adjustment, but then other nodes would reject such a block, and she would lose the value of the new issuance, having wasted time and energy for nothing. Miners spend money to solve puzzles, and thus it’s quite safe to assume they want to enjoy the associated rewards, creating blocks that aren’t rejected, at least in scenarios where they only follow financial incentives endogenous to the system.

Mining Fees

This solution, while brilliant, still lacks incentives for miners to include other people’s transactions. They could just opt to save the computing power needed to verify scripts and signatures (which, while not being as much as the one needed for hash collision, is still relevant) and to include only their own valid issuances in otherwise empty blocks. Also, the diminishing amount of sats allowed in such issuances, due to the controlled-supply paradigm, would reduce (even discounting for an increase in sats’ purchasing power) the incentive to solve blocks at all, eventually canceling it completely at the end of the last era, when there will be no inflation. You solve this problem by introducing “mining fees”: a small “extra” that users can attach to their transactions to incentivize miners to include them. It works like this: The system allows miners to include in their reward transactions, along with the issuance of newly “minted” sats (compatible with the current era), also the difference in sats between created and consumed UTXOs of all the valid transactions included in the block. Fees never depend on the amount transacted, but only on the transaction size (script complexity, number of signatures, etc.) and the desired priority within blocks.

Scaleness (and Darkness) Problems

The minimum mining fee necessary for a transaction to be included in a block fluctuates depending on supply and demand of “block space.” On the supply side, the number of transactions that can be added to the timechain are limited by a maximum block size (less than 4 megabytes for each block) and a maximum block rate (about one every 10 minutes). On the demand side, each user has different constraints and preferences (some can wait more to pay less, some can pay more to wait less, some use wallets with excellent dynamic fee estimation, some don’t). In general, a rising demand for block space would imply a rise in mining fees. This clearly limits the scaleness of the system (in particular, since miner fees are independent from the amount of value transferred, we could say that it actually reduces divisibility). More, in general, using a timechain implies that every node in the network must forever keep track of everything: Every single on-chain transaction must be downloaded and verified by every actor who will use the system for its entire history, even far into the future. Such a system is clearly not scalable. It also lacks darkness, since everyone has to keep a copy of every transaction forever, enabling any kind of forensic analysis and deanonymization attempt.

It would be possible to make the situation look better for some users, at the cost of creating another more “privileged” class of users. For example, if you increase the size and frequency of blocks, then the block-space supply increases, and its price decreases. But the cost of running nodes, with the ability to independently verify the validity of transactions and blocks, increases way faster than said supply, centralizing the topology of the entire system. Sure, a new class of specialized nodes could serve as some kind of “signed message” to inferior, non-validating users, giving them some guarantee that a transaction is valid. After all, coinage was introduced in order to delegate to a few specialized trusted entities the expensive task of verifying precious metal coins. But, just like coinage, this strategy (knowns as “SPV”) implies a strong centralization, with all the attached risks of political interference or censorship by the likes of Mallory.

A New Paradigm: “Off-Chain”

There’s a smart way to mitigate the fundamental scaleness limits of global consensus systems without sacrificing its decentralization. We will call it the “off-chain paradigm.” The idea is simple: Just refrain from committing every transaction to a block until it’s strictly necessary, keeping most of the traffic off the public timechain (with its expensive global consensus) and only using it for conflict resolution and periodic settlement. This evolution is similar to the way people use courts and contracts in common-law systems: Courts can create publicly binding precedents, reaching some sort of “legal global consensus,” but they are comparatively slow and expensive, so most trading parties usually only sign private bidirectional contracts, asking courts to verify and enforce them only when conflicts arise or when some periodic settlement is due. Advanced smart contracts could be used to make this kind of “recourse” trust-minimized: Unlike an actual legal system, the decentralized timechain could avoid human bias and corruption, relying mostly on cryptography and code. Unlike the credit certificates discussed in the context of virtualization, off-chain transactions are not “virtual”; they are actual valid transactions, with high probability of being enforced by the system regardless of the honesty of the parties involved.

You soon realize that this kind of paradigm could highly improve the darkness of your system as well. Instead of having all the nodes registering all transactions forever, most of those transactions would be exchanged privately between the interested parties alone, making forensic analysis by malicious eavesdroppers harder, costlier, less complete and less reliable.

The main implementation of such a strategy is a secondary network of pre-funded, bilateral “payment channels” that can route transactions across many hops in a trust-minimized, atomic way. Users call it by a very poetic name: “the Lightning Network” (the acronym for which is often included in the label of the whole protocol suite of your system, named “LNP/BP” as analogous to the historical “TCP/IP”). But there are other minor instances of the same paradigm; for example, several techniques to keep the actual script off the timechain until needed, saving block space and privacy as well. (People call these techniques many strange names, like “Taproot,” “Graftroot,” “g*root,” “Scriptless Script” and so on.)

With the introduction of these final pieces of technology, your users finally have everything they need to use the system in real life, in order to take back some of the most important features of money. Thank you, “Satoshi”!

Image courtesy of CryptoScamHub

Image courtesy of CryptoScamHub

You have come a long way since your early caveman innovations, far in the past. Now, only the future can tell us if this Plan ₿ of yours will work out. To the moon. A final thank you to Nicki DiCicco for her cover art and to CryptoScamHub for his meme art contributions to this series!