Bitcoin: Winner Takes Most or Winner Takes All?

| If you find WORDS helpful, Bitcoin donations are unnecessary but appreciated. Our goal is to spread and preserve Bitcoin writings for future generations. Read more. | Make a Donation |

Bitcoin: Winner Takes Most or Winner Takes All?

Exploring market share capture in cryptocurrencies

By Misir Mahmudov and Yassine Elmandjra

Posted January 7, 2019

This series will explore how the winner-takes-all or winner-takes-most notion applies to the cryptocurrency market. In Part I, we will provide a high-level overview on the evolution of monetary systems up to the inception of cryptocurrencies, shedding light on the limitations of previous forms of money. In Part II, we will explain why the clear winner, likely Bitcoin, should capture most, if not all cryptocurrency market share. In Part III, we will apply this reasoning to the global economy and determine the extent to which the cryptocurrency market may capture a share of global base money.

Part I: The Quest for a Global Money

Before the rise of any universal monetary standards, barter was a common means of direct exchange. Subject to the problem of coincidence of wants, civilization came to understand the impracticability of barter. In an attempt to provide a solution to this impracticality, indirect exchange emerged and was made possible with intermediary goods such as seashells, glass beads, and cattle. Over time, modern technologies (like mass utilization of hydrocarbon fuel energy and importation) considerably advanced manufacturing and transportation, making the world increasingly connected. Exploration and intercontinental trade became more prevalent, and the standard traits of money evolved to accommodate a more global context. This ultimately undermined existing media of exchange, as the lack of absolute scarcity and low costs of production could not provide money guarantees and were exploited by increasingly advanced technologies. Specifically, outside groups learned how to easily reproduce region-specific forms of money. Unaware of the absolute abundance of their money, nations suffered severe wealth dilution. [1]

As the limitations in existing forms of money began to manifest, specific properties of monetary goods emerged that better fulfilled money’s store of value and medium of exchange functionalities, including scarcity, durability, portability, fungibility, verifiability, divisibility, and established history. Through a process of monetary natural selection, goods competed with each other based on these demanded attributes and in the 19th century, the world converged to gold as the global monetary standard.

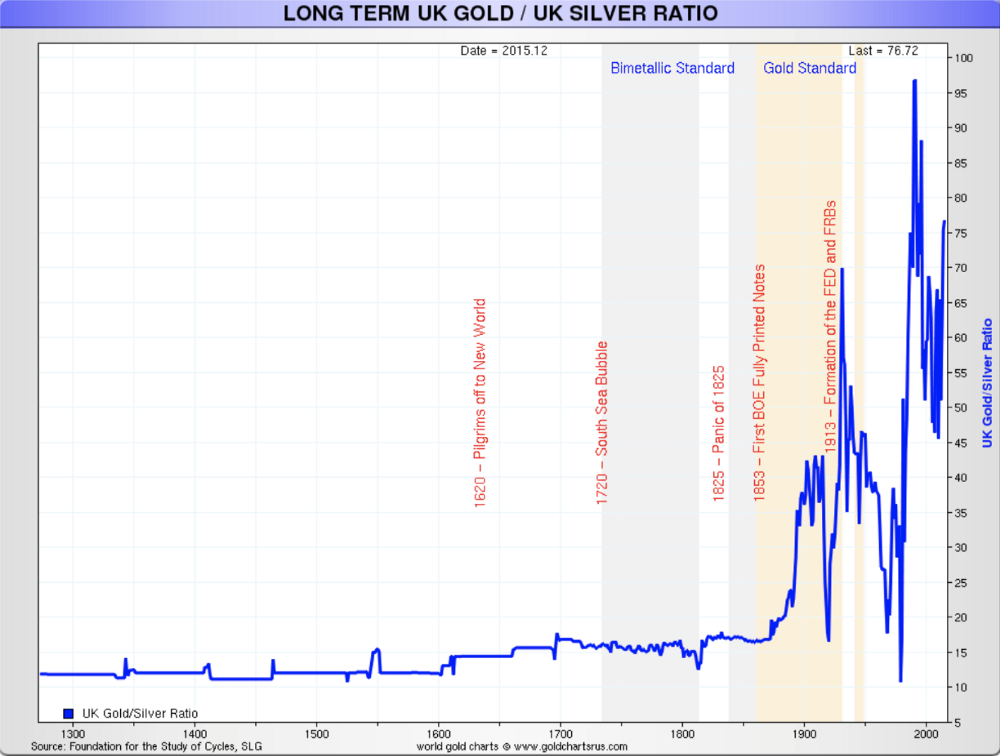

With the rise of gold, other forms of commodity money took form. Silver as a money was popularized because of the high costs associated with using gold in day-to-day trade. Silver’s lower value per unit weight relative to gold made it easier to use for smaller transactions. [2] For centuries, the gold to silver ratio remained between 12 and 15 and was recognized as the bimetallic standard. But this bimetallic standard ended up as nothing but a temporary phenomenon adopted to overcome insufficient technology. With the introduction of paper money backed by gold, which gave people the ability to trade any amount of value represented in gold terms, silver’s monetary role was subsequently reduced. The graph below shows how rapidly the gold to silver ratio soared after the popularization of paper money.

Gold / Silver Ratio https://www.goldbroker.com/news/gold-and-silver-correlation-988

Gold / Silver Ratio https://www.goldbroker.com/news/gold-and-silver-correlation-988

Through financialization, gold’s limitations to serve as a global money began to surface. In particular, gold’s physical nature and high value per unit weight made it vulnerable to centralization and its detrimental effects. With gold’s lack of portability and the high friction in using a scale to measure the amount of gold in every transaction, the state intervened to establish standardized units by minting (coining) gold coins. As citizens got acclimated with the conferred legitimacy and the infrastructure built around standardized units, the state felt comfortable engaging with what is known as ‘coin clipping’, a form of debasement whereby jurisdictions would reduce the content of gold in a coin and use the excess gold to finance expenditure at the cost of citizens.

Later, goldsmiths, who provided services for custodying precious metals, introduced promissory notes (IOUs) that were redeemable for metals. These notes (paper money) eventually became commonly used in exchange. The goldsmiths understood that they could lend out more notes than gold they had stored in their vaults because people were unlikely to simultaneously redeem their gold reserves. This practice became known as fractional reserve banking. Goldsmiths, which later became banks, issued receipts in excess of the represented metal and generated massive profits as a result.

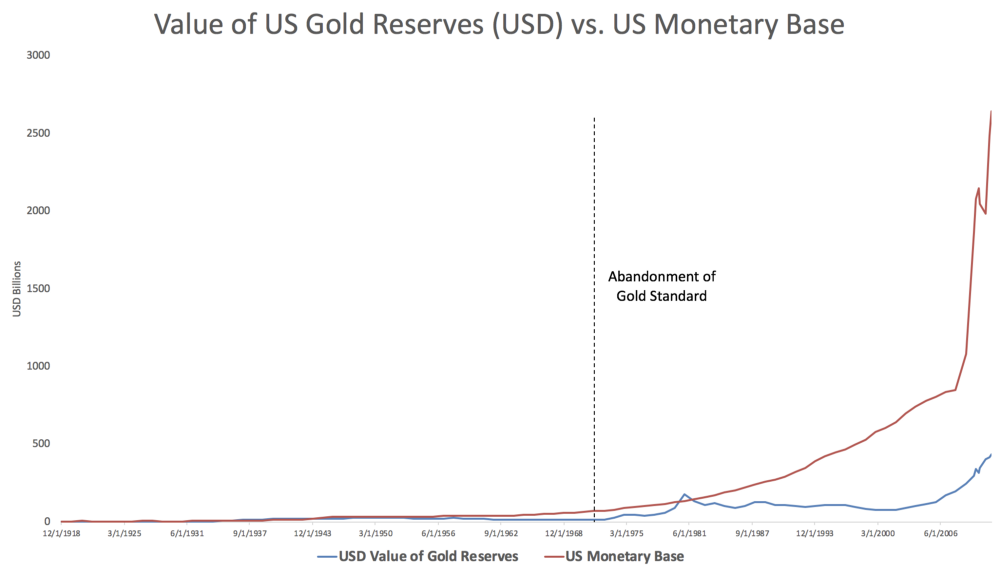

The 18th and the 19th centuries saw the formalization of the Gold Standard as the proliferation of banknotes and the less sound nature of silver made itself known. The Gold Standard was a monetary system whereby a country’s monetary supply was directly linked to the value of its gold reserves, putting a cap on a nation’s ability to inflate supply. By the 20th century, states began exploiting the limitations of gold and abusing the practice of fractional reserve banking, ultimately removing its viability as a global money. The US was able to centralize gold reserves, often forcefully confiscating gold from its citizens, [3] and began printing money in excess of their underlying reserves. Instead of attempting to redeem themselves, the US under Richard Nixon cancelled the convertibility of the dollar into gold and officially abandoned the Gold Standard in 1971. Ties between gold and paper money were in turn severed, marking the beginnings of fully unbacked fiat currencies. Below is a chart of the US monetary base expansion relative to the value of US gold reserves.

Currencies… Currencies Everywhere.

Today, there exists over 180 currencies across 195 countries. The reason for such an anomaly is simple: there is no free market for currencies. Currency markets have been restricted by governments in order to maintain financial control. There are numerous laws and institutions set up for the exact purpose of inhibiting a free market monetary system. This includes enforced borders, legal tender laws, capital controls, state decrees, seigniorage privileges, local control, local monopolies on violence, debt extinguishing laws, capital gains taxes, implicit bailout guarantees for banks, central banks and dozens of other artificial barriers. This type of legislation forces people around the world to keep using inferior currencies under the threat of direct or indirect violence or repercussions. The centralized nature of the financial system and flows allows governments and institutions to impose these restrictions and greatly limit people’s ability to express their true demand for superior, more competitive currencies. Fiat money’s soundness is now dependent on an authority’s ability to enforce legitimate monetary policy. People living in countries like Venezuela are unable to reliably store their wealth due to hyperinflation induced by irresponsible monetary policy and limited availability of more reliable currencies due to strict capital controls. In addition, as the only form of legal tender, citizens are obliged to pay taxes in and accept the inferior currency in exchange for goods and services. The more competitive currencies, like the dollar, that do make their way into countries like Venezuela, are sold at large premiums as the high demand is not met by the controlled supply. Until recently, citizens of countries like Venezuela had no way to opt out of this system and were forced to adopt easy money.

The government’s control of money has made it vulnerable to gross mismanagement. In an interview in 1984, Friedrich Hayek famously said: “I don’t believe we shall ever have a good money again before we take the thing out of the hands of government. We can’t take it violently out of the hands of government, all we can do is by some sly roundabout way introduce something that they can’t stop.” And, in Free Market Monetary System , Friedrich Hayek notes that “ the monopoly of government of issuing money has not only deprived us of good money but has also deprived us of the only process by which we can find out what would be good money. We do not even quite know what exact qualities we want … because we have never been allowed to experiment with it. We have never been given a chance to find out what the best kind of money would be.”

Enter Bitcoin: The Experiment That Allows Us To Experiment

In 2008, Satoshi Nakamoto proposed Bitcoin, an alternative financial system free from top-down control. Bitcoin, “a system for electronic transactions without relying on trust”, was not created to fit existing governments and financial systems.

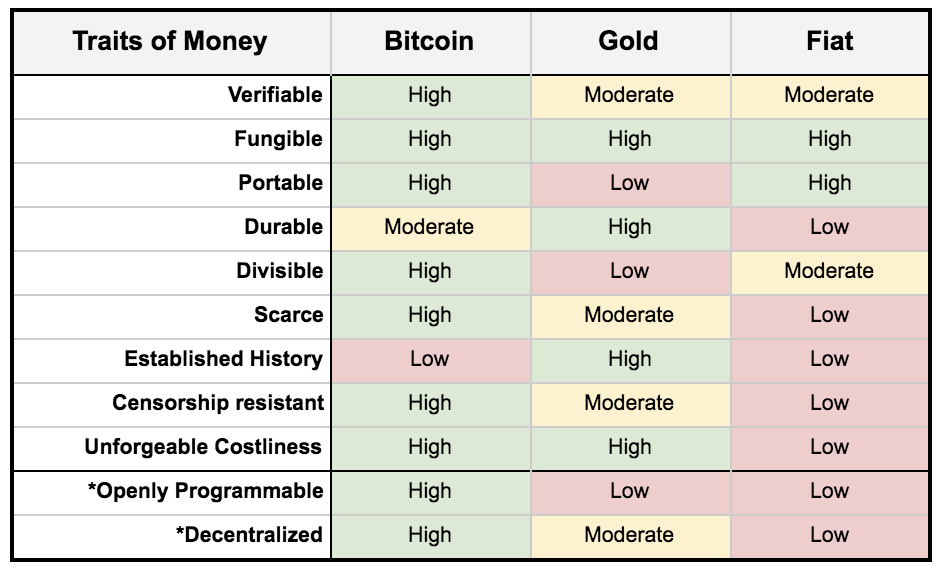

Bitcoin is the experiment that allows us to experiment. Unlike any money of the past, Bitcoin is borderless, permissionless, censorship-resistant, and easily verifiable. As such, Bitcoin may precisely be this “sly roundabout way” that bypasses prohibitive mechanisms and legacy financial institutions that restrict people’s access to a free market for money. Bitcoin is often referred to as digital gold because it maintains and improves upon most of gold’s properties, including scarcity and unforgeable costliness. Given its digital nature, bitcoins are easily divisible, portable and unseizable, which enables it to be much better protected from the threats of centralization and the fate experienced by gold. First introduced by Vijay Boyapati and then further expanded upon by Dan Held, below is a table assessing Bitcoin, gold and fiat’s ability to fulfill the traits of money.

https://medium.com/@danhedl/planting-bitcoin-56bd1459cb23

https://medium.com/@danhedl/planting-bitcoin-56bd1459cb23

The Rise of Cryptocurrencies

Cryptocurrencies are first and foremost money . With the exception of a few, ‘crypto-tokens’ are either clearly intended to be money or are intended to be money but are obfuscated by technological jargon. As Bitcoin’s community grew and its prices rose, other cryptocurrencies (often referred to as altcoins) began to hit the market. Many of these cryptocurrencies were built in an attempt to iterate and improve upon Bitcoin’s “fundamental design flaws” and “limited functionality”. In 2018, ten years after Bitcoin’s inception, there are now over 2,000 cryptocurrencies .

Contrary to the 20th century’s locally nationalized market for money, the cryptocurrency market much better resembles a competitive private market where no coercive monopolies distort price signals by preventing competitors from entering. Given the open source nature of cryptocurrencies, anyone is free to create their own or modify existing ones, which is as simple as copying the publicly available code of an existing cryptocurrency. This in turn encourages open and inexpensive experimentation.

The open source nature of cryptocurrencies is a promising mechanism to determine what the natural money of society might be. As Jörg Guido Hülsmann highlights in the Ethics of Money Production, “the only way to find out the natural money of society is to let people freely associate and choose the best means of exchange out of the available alternatives.”

Assuming operation under a free market, the question then becomes to what extent the natural money captures market share. While today’s world has manifested itself differently, a glimpse of a winner take most, if not all, reality was seen with gold. Assuming a long-term time horizon, this same glimpse of reality may play out with cryptocurrencies, this time as more than just a temporary phenomenon.

In Part II, we explore in depth the validity of a winner-takes-all narrative. By defining market size to be the total monetary premium of all cryptocurrencies and deriving what drives a good’s monetary premium, we shed light on the merits of such a narrative.

(1) Rai stones in Yap and glass beads in West Africa (2) Using gold was impractical for daily purchases as it required measuring and dividing it into small quantities. (3) In 1933, Roosevelt’s Executive Order 6102 forbade the hoarding of gold coin and bullion