Bitcoin Has No Intrinsic Value — and That’s Great

| If you find WORDS helpful, Bitcoin donations are unnecessary but appreciated. Our goal is to spread and preserve Bitcoin writings for future generations. Read more. | Make a Donation |

Bitcoin Has No Intrinsic Value — and That’s Great.

By Conner Brown

Posted May 8, 2019

Intrinsic Value. Bitcoin skeptics love to talk about it. Their argument is typically as follows: “Bitcoin cannot be used as a money because it does not have any intrinsic value as a commodity. For something to be a viable money, it must first be accepted and used for some other commodity purpose intrinsic to the item then slowly become a money over time. For example: because gold can be used in jewelry and electronics, people naturally stockpile it to store value.”

Previously, Bitcoiners have made several compelling arguments against this on the grounds that 1) intrinsic value is subjective and 2) Bitcoin does have intrinsic value as a good for censorship resistant payments. Here I will argue that Bitcoin skeptics are right. Bitcoin has no “intrinsic value” as a commodity, but that’s a great thing for Bitcoin (and the rest of the world).

Inside the Mind of a Skeptic

Intrinsic value is an old idea. Even Aristotle wrote about the importance of money being “intrinsically useful and easily applicable to the purposes of life, for example, iron, silver, and the like.” It’s no wonder that this idea has persisted — commodity value has been essential to humankind for thousands of years and is directly evident to the layman.

Despite its ancient origins, intrinsic value is not directly linked to monetary functions. A good money needs to be many things — portable and easy to trade, scarce and durable to store value, fungible and divisible as a unit of account — but an alternative commodity use is not one of them. So why do many critics claim money needs intrinsic commodity value?

There appear to be two main reasons.

Appeals to History

Many skeptics denounce Bitcoin’s lack of intrinsic value simply because they are accustomed to stores of value doubling as commodities. Put simply — they are living in the past. Many have made this argument about previous technological improvements by wrongly assuming that previous trends would hold true.

The fact that all previous forms of value had a physical form does not mean a new store of value must also be physical. People were making similar arguments about physical shopping during the rise of the internet. Here is a hilariously bad takefrom a Newsweek contributor in the 90’s, arguing that because we’ve always had physical sales in the past, physical sales will not be replaced by the internet. Bitcoin skeptics claiming money needs to be a useful physical commodity will seem equally ridiculous a decade from now.

In fact history shows that commodity value is far from a requirement for a money. Nick Szabo explains in the beginning of his classic piece“Shelling out: The Origins of Money” that societies have used otherwise “useless items” for storing and communicating value. These glass beads had many strong monetary properties and were used for trading throughout Africa and parts of North America, but they had little use as a commodity. The Rai stones used by the Yap people are another example of a store of value without commodity use.

Figure One: Glass Beads formerly used as money among tribes in Oklahoma.

Figure One: Glass Beads formerly used as money among tribes in Oklahoma.

Appeals to Authority

Today, many who voice concerns about intrinsic commodity value trace their arguments to Austrian economists such as Menger, Mises, and Rothbard. These writers strongly emphasize the importance of money and its impacts on society. For them, commodity value and money have been inseparable since their earliest writings. One of Menger’s seminal works, On the Origins of Money, begins by describing money as “the fact of certain commodities becoming universally acceptable media of exchange” (p. 1). Mises later built upon this understanding. In The Theory of Money and Credit, Mises writes, “we may give the name commodity money to that sort of money that is at the same time a commercial commodity; and the name fiat money to money that comprises things with a special legal qualification” (p. 61).

Following in the mental footsteps of previous Austrian economists, many critics apply these outdated frameworks to attack Bitcoin. Niels van der Liden, one of the first Bitcoin skeptics (when a bitcoin was 77 cents!), rejected Bitcoin for this very reason. He claimed it would not work because “nobody could do anything with them but trade them.” Therefore, he concluded they had no use as commodities and would not work as money.

While commodity and fiat monies were the only two possibilities for early Austrian economists (outside of credit instruments), times have changed. In our digital age, the distinction between commodity and fiat money has lost its value. It should be immediately apparent that Bitcoin does not fit neatly into this dichotomy — it has no use as a physical commodity but also does not exist through any legal decree. We can now hold and trade digital money wholly independent of the simple force of law. Instead, Bitcoin’s monetary properties are guaranteed with rules and logic embedded into its coded DNA. Through this purely digital existence, Bitcoin lives as a money free from the restraints of the physical world.

Solving the hard money paradox

In fact, if the skeptics had done their homework, they would realize that Mises was a Bitcoiner at heart as well. He recognized the problems inherent in commodity money but saw gold as the best of bad choices. In The Theory of Money and Credit, Mises laments that even a monetary system based on gold is still subject to “considerable disadvantages” regarding “not only the fluctuations in the supply of money and the demand for it, but also fluctuations in the conditions of production of the medal and variations in the industrial demand for it” (p. 238).

Mises correctly points out that commodity uses of money create price distortions as fluctuating industrial demands push and pull on the shared supply.Hard money has always been associated with unique physical attributes — good for money, but also other industries. In this regard, gold’s incredible versatility across many different industries magnifies this harmful effect.

The physical world also brings other monetary restraints. Something found in nature cannot be routinely distributed over time. Here, Bitcoin’s predictable, periodic emission allows for supply calculations decades into the future that are not possible outside the digital world. A physical item’s supply also cannot be audited. At any moment someone could find previously unknown amounts of gold and radically dilute ownership without current holders knowing about the sudden changes in supply — similar to how cowry shells were secretly inflated by European tradersto the detriment of African tribes. With Bitcoin’s digital nature, anyone can audit the entire supply and know the exact amount created at any time.

With these advances, it’s silly to cling to the Austrian economists giving advice for their unique historical moment. Those writers were not laying down universal constants. Even they realized their limits and hoped for better forms of money than precious metals. New circumstances require new theoretical foundations — and Bitcoin gives us just that.

Bitcoin as the key to unlocking captured utility

In our present day, it just so happens that the best stores of value are also those that have some element of utility as a commodity. The key distinction here is that gold, real estate, or any form of commodity money is not a store of value becauseof its utility as a commodity, but despitethat utility!

When someone decides to hold gold or any other asset for a monetary purpose, they make a clear and conscious choice to use it for its wealth storage properties instead of as a useful commodity. Rather than creating electronics parts or jewelry, holding a gold bar puts gold’s monetary properties to work. While this decision may appear innocuous, this can bring harmful economic consequences. Large numbers of people storing their value in a specific commodity with hopes of wealth storage often leads to extreme waste and speculative bubbles.

Real-estate is a particularly egregious example of this effect. Today, speculators chase “golden concrete” to protect their wealth. Developer Michael Stern explains “the global elite is basically looking for a safe-deposit box” and many have decided to invest in Manhattan properties to store their funds. By doing this, they are using their luxury apartments for saving instead of for living. As a result, journalists noted “according to the Census Bureau, throughout a sweeping stretch of midtown — from Forty-ninth to Seventieth streets, between Fifth Avenue and Park — nearly one in three apartments is completely empty at least ten months a year.” Similar trends are spreading through large cities worldwide. As The Guardian reports, “[t]he trend for the world’s super-rich to invest in prime London property as a way to safeguard their wealth, without the need to secure a rental income, has meant the number of empty homes in Kensington and Chelsea rose 22.7% over the same period and 8.5% since 2015.” As the elite continue to pour wealth into these commodities, bubbles begin to rise to the top. A recent report by UBS shows just how risky this has become.

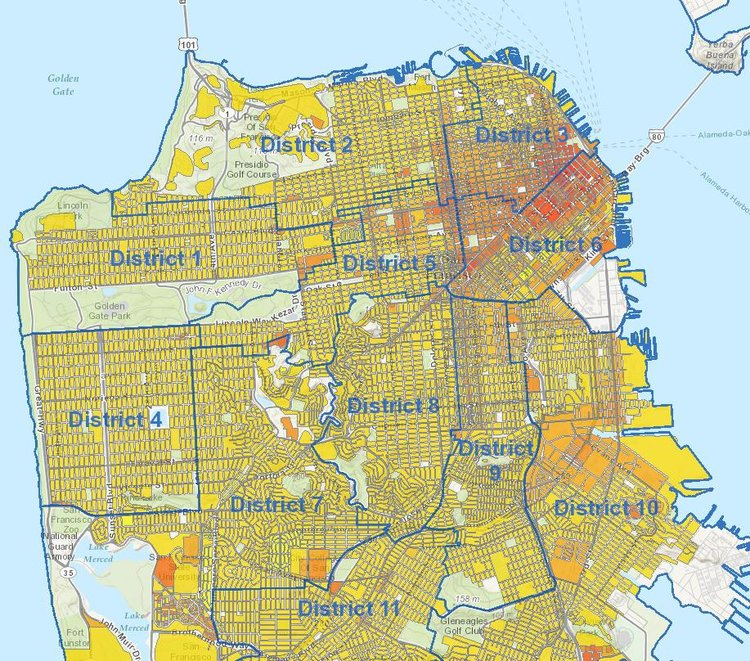

Not only are properties sitting empty, using homes as a significant store of wealth destroys healthy market incentives for new housing development. San Francisco and the rest of the California housing market are obvious examples of this phenomena. Below is a map illustrating San Francisco’s zoning regulations. All areas shaded yellow are limited to a building height of 40 feet.

Figure Two: A map of San Francisco’s local zoning laws.

Figure Two: A map of San Francisco’s local zoning laws.

These regulations are a clear impediment to building new affordable housing to meet demand. Given the repercussions on the average residents and rent prices, why do they exist? One large cause stems from existing homeowners lobbying for artificial restrictions on supply to preserve their wealth. A recent report by the Legislative Analyst’s Office for Californianoted that “residents may see new housing as a threat to their financial wellbeing. For many homeowners, their home is their most significant financial investment. Existing homeowners, therefore, may be inclined to limit new housing because they fear it will reduce the values of the homes.” Because the average buyer does not have a reliable store of value in their money, homes are considered by many to be the best place to safeguard one’s wealth. This naturally causes homeowners to then lobby to constrict home supply so their precarious wealth is not diluted. In this sense, the real-estate markets only have store of value properties through artificially generating scarcity.

Bitcoin would not solve this problem entirely, but it gives potential homebuyers an alternative way to securely store wealth over time. Allowing people to rethink their financial decisions may ease the pressure against building new homes. With new affordable development, cities would be able to increase their density and improve the quality of life for all residents. For example, research modeling suggests that if San Francisco were able to increase its housing density, this could significantly reduce the city’s carbon footprint, increase the city’s walkability, and improve the quality of community life — all while preserving the signature sunny California environment.

Even securing the network would be cheaper, with higher quality ASICs!

Even securing the network would be cheaper, with higher quality ASICs!

Gold is another great example. As individuals sell their gold to buy bitcoins, gold that was previously held for its wealth storage properties can be put to work in electronics, medical devices, and aerospace pursuits. It can even be eaten! Gold stored around the world can be used to benefit society through cheaper and higher quality products — and make previously impossible endeavors much more affordable. With Bitcoin we can actually afford to go to the moon. So when you hear goldbugs extol its amazing societal uses — they are right — but they are really making a case for digital gold. By acting as a global store of value, Bitcoin unlocks that stored commodity utility that we’ve had to set aside because our world has always lacked a pure money.

Final Thoughts

Instead of locking up useful resources to store wealth, Bitcoin gives humans the ability to store wealth free from the opportunity cost inherent in storing commodities. This global, permanent, and accessible store of wealth is forming a solid bedrock for future economies around the world. As funds move from other asset classes towards Bitcoin, this newfound supply will create better access for affordable housing, rejuvenated urban environments, higher quality consumer goods, and more.

Yes, Bitcoin has no intrinsic value and for that we should be thankful.

A special thanks to Karina Kauffman, Dan Held, and the Bitcoin Observer for their incredible help.