Bitcoin Astronomy: Part II

| If you find WORDS helpful, Bitcoin donations are unnecessary but appreciated. Our goal is to spread and preserve Bitcoin writings for future generations. Read more. | Make a Donation |

Bitcoin Astronomy: Part II

By Dhruv Bansal

Posted December 9, 2020

This is Part II in a series of speculations about the hyperbitcoinized future. In Part I, we defined the First Law of Bitcoin Astronomy and described how it incentivizes searching for energy to power our growing civilization.

In this part, we continue to follow the energy and speculate about how money and society coevolve as humanity expands through space. We begin with a brief review of Part I.

First Law 101

In Part I, we speculated about a hyperbitcoinized humanity where bitcoin has become much more than just a currency or even a global financial system. In the future, bitcoin is deeply integrated into energy, telecommunications, logistics, and other sectors of Earth’s economy. Secondary and tertiary layers of networks settling into bitcoin are how markets, supply chains, and political systems organize themselves.

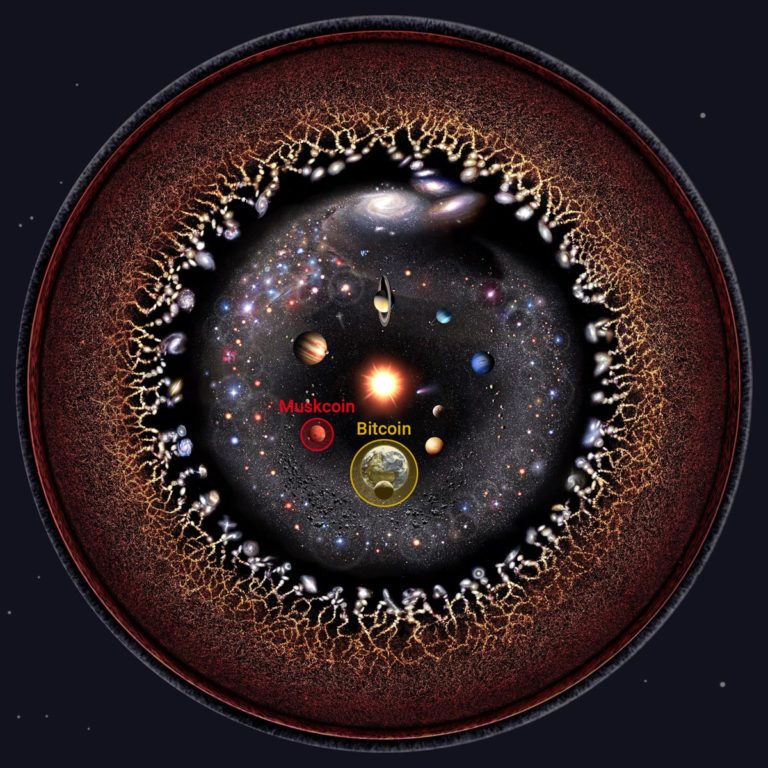

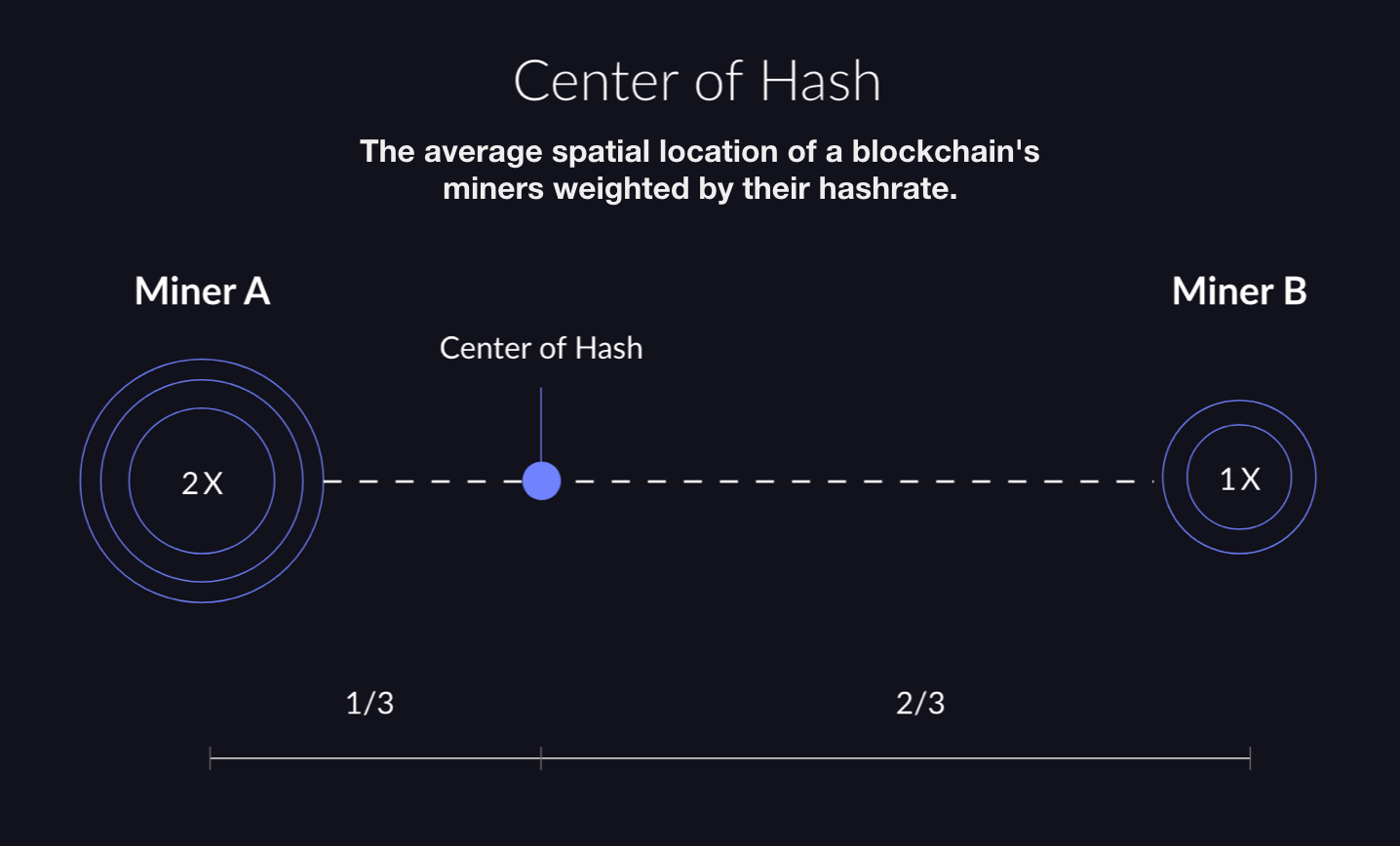

The “Center of Hash” was defined in Part I of this series.

Humanity is also beginning to settle other planets such as Mars. This led us to explore how bitcoin works when great distances separate users and miners. We introduced the idea of a center of hash (above) and explained how it leads to the First Law of Bitcoin Astronomy: proof-of-work mining is not feasible far from the center of hash of a blockchain. All of a blockchain’s miners must be co-located within the same hash horizon — a spatial sphere with a diameter comparable to the the distance light can travel within that blockchain’s block time. Bitcoin’s choice of a 10 minute block time places Mars (at an average distance of 12 light minutes) outside of Earth’s hash horizon. Martians will be able to use bitcoin, but never mine it!

Mining is one of the most important industries of the hyperbitcoinized future. It’s not just about capturing transaction settlement fees — the ability for anyone to turn energy directly into money incentivizes broader collection of energy and optimizes its distribution. Eager to kickstart this virtuous cycle (and a wave of financial speculation), distant colonies will launch their own bitcoin-like blockchains.

We followed the launch of Muskcoin, the first of these blockchains, on the planet Mars. The launch of Muskcoin is a kind of economic and political revolution. Terran miners will not support it, preferring to keep Martian transaction fees accumulating on Earth. The First Law of Bitcoin Astronomy is the reason Martians launch Muskcoin, but it will also be why Muskcoin survives; Terran miners are too far away from Muskcoin’s center of hash to prevent it from becoming the new currency of the Red Planet.

This pattern of expansion and revolution will repeat throughout the future. As great distances divide our civilization, the First Law ensures that those on the fringes will have both the incentive and the capability to launch their own blockchains. These pioneers will settle the outer planets, and eventually nearby stars, simply because they are far away.

Kardashev Civilizations

Before we continue our speculations, it will be useful to introduce some terminology for describing civilizations by their energy usage. Nikolai Kardashev’s famous scale categorizes civilizations as follows:

- A Type I civilization uses energy on a planetary scale (~1017 Watts)

- AType II civilization uses energy on a stellar scale (~1026 Watts)

- AType III civilization uses energy on a galactic scale (~1037 Watts)

This scale is not precise and is more than a little arbitrary, but it does capture the vast gulf in energy usage between civilizations of different types: a Type II stellar civilization, for example, uses billions of times more energy than a Type I planetary civilization. The three original categories have since been extended (Type IV, Type V, &c.) and interpolated. A Type 2.1 civilization, for example, would use more energy than a Type II stellar civilization but less than a Type III galactic civilization.

Science fiction frequently describes fantastic megaprojects of advanced civilizations, such as space elevators and Dyson spheres, but it seldom articulates how they pay for it all. How can money develop the reach to coordinate society across solar systems and galaxies? What size market is required to settle the sale of a star system? Which reserve currency would an immortal future investor choose to hold? These questions are ignored by most science fiction writers who view money as either uninteresting because it’s just like today’s or irrelevant because the future is post-scarcity.

…if your theory is found to be against the second law of thermodynamics I can give you no hope; there is nothing for it but to collapse in deepest humiliation.

– Sir Arthur Eddington

We believe that the laws of thermodynamics are inviolable. Energy will always be scarce, and using it will always create entropy through waste heat. The only quantity in the universe with infinite supply is human ambition. No future society will therefore ever be post-scarcity. For humanity, this means money and markets — and therefore blockchains — will always be useful for optimizing resource collection, distribution, and allocation.

Kardashev Blockchains

We believe money will scale with society’s energy usage.

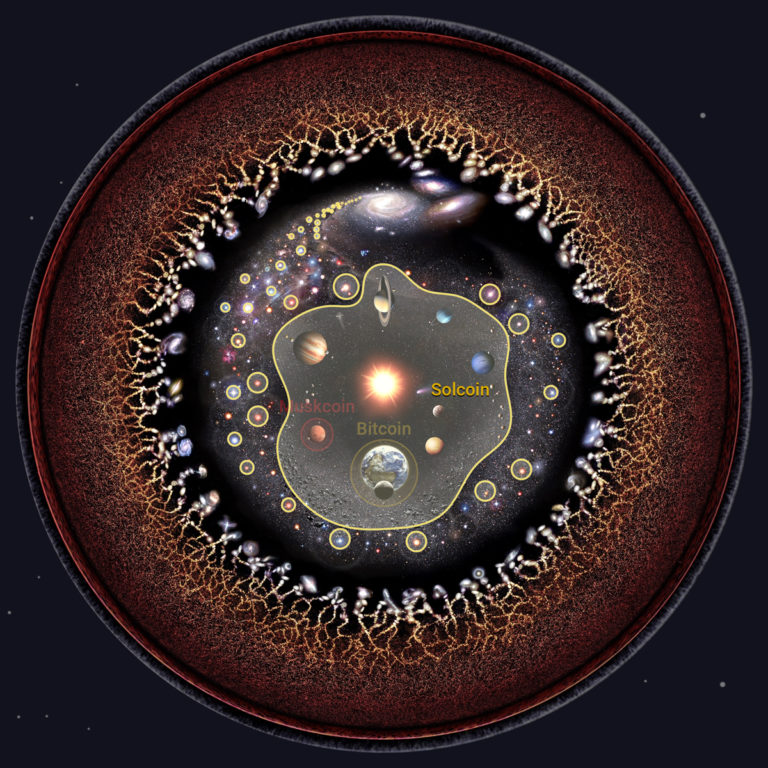

Today, at the dawn of bitcoin we are (by some measures) a Type 0.7 “sub-planetary” civilization. By the time of the Muskcoin revolution, our burgeoning interplanetary civilization will have risen to somewhere between Type I and II on the Kardashev scale, though much closer to Type I.

As we continue towards becoming a Type II civilization, we will outgrow Type I “planetary blockchains,” such as bitcoin or Muskcoin. We will still value these currencies, but will forge a new, stellar blockchain to span our entire solar system. We will call this Type II blockchain Solcoin, as it will come to be used for most trade occurring in orbit of the star Sol, our sun.

But money doesn’t just scale in response to society’s energy usage, it causes it: blockchains of higher type bootstrap civilizations of lower type up the Kardashev scale. Bitcoin was a Type I blockchain built by a Type 0.7 civilization. It incentivized energy collection near the Earth, propelling us up into orbit and out into the solar system towards becoming a Type I civilization. Solcoin is a Type II blockchain built by a Type 1.x civilization. It will incentivize energy collection across the entire solar system, powering megastructures and interstellar missions, enabling our species to expand through our galactic neighborhood.

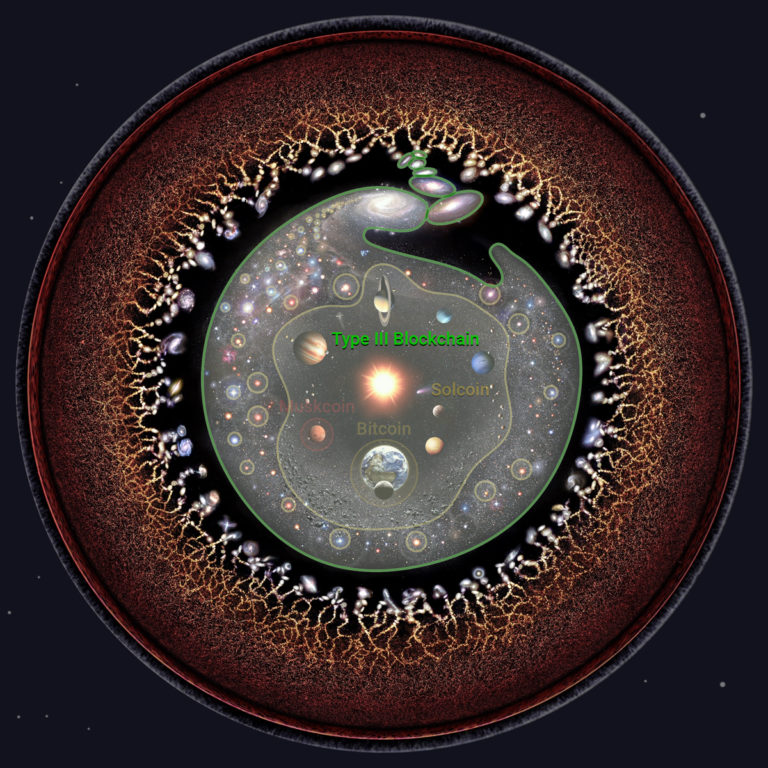

When humanity eventually reaches other stars, we will launch blockchains there, too — first planetary, then stellar. Our eventual Type 2.x interstellar society will launch Type III galactic blockchains. This positive feedback between expanding societies and new blockchains will repeat at ever larger scales determined by the distribution of matter in the universe.

We’ll begin our story with the origin of Solcoin on the once great planet of Earth, sometime after the Muskcoin revolution.

Type I Civilizations Launch Type II Blockchains

The Muskcoin Revolution was a shock to many Terrans. Earth was the oldest, most populated, and most developed world, and the hashrate of Terran miners was tremendous. Yet Mars, a small colony that would have failed without continued investment and nourishment of Earth, successfully revolted against bitcoin.

The crucial factor in the success of this revolution was the Martians’ choice of a block time short enough to place Earth outside of Muskcoin’s hash horizon, preventing Terran miners from mining Muskcoin. Had Martians chosen to endow Muskcoin with a block time of several hours, Earth would have been within Muskcoin’s hash horizon. The massively larger Terran hashrate would have out-competed Martian miners, allowing them to hash bomb Muskcoin, destroying it and the revolution without any shots fired.

Short block times are a form of economic protectionism enabled by the finite speed of light.

Martians and other potential revolutionaries intuitively understand this relationship: short block times allow fledgling blockchains to defend themselves against the predations of powerful incumbents. Long block times not only make secondary and tertiary layers of a blockchain-based economy more challenging to engineer, they also cede power to faraway interests. No revolution would be so foolish as to start a blockchain with a long block time.

The Decline and Fall of the Terran Empire

But what about an empire?

Like the American Revolution centuries prior, the Muskcoin revolution became a model for other colonies seeking independence from Terran economic and political control. Powerful interests on Earth, like the British Empire before them, are faced with the prospect of continually diminishing influence, as faraway colonies grow and, inspired by the example of Mars, demand their independence.

Clever Terrans will realize that a blockchain with a long block time may be exactly what is needed to curtail future revolutions. Martians used bitcoin on Mars for many years before they launched Muskcoin; it was the inability to mine bitcoin and the absence of the virtuous cycle of mining that prompted the revolution.

Most of the solar system’s mass is within a light day of Earth. If Terrans were to launch a blockchain with a block time of several days, its hash horizon would encompass all miners in the entire solar system. This will lead them to suggest Solcoin, the first Type II stellar blockchain.

Terrans hope Solcoin will transform potential colonial revolutionaries into productive miners, all hashing together within a single, solar-system wide market. A single money, they’ll argue, is more efficient than many separate monies. They’ll advocate for citizens of faraway colonies to use Type I planetary blockchains such as bitcoin for their daily transactions but mine Solcoin for the health of their economies.

Such an arrangement would be of great benefit to Terran miners. Large distances and short block times cut off their tremendous hashrate, largest in the solar system, from the fee markets of blockchains such as Muskcoin. Solcoin is an interplanetary fee market that all miners in the solar system can compete in. Since Terrans have the highest hashrate, they would dominate this market, capturing settlement fees that currently go to miners of other blockchains.

Solcoiners are selling their hashrate to interplanetary society. And, you know, there’s no such thing as interplanetary society. There are individual planets and moons and there are asteroids.”

– Stargaret Hasher, 2187

This point will not be lost on the governments, businesses, and people living far from Earth, already using or contemplating their own planetary blockchains. Local mining industries solar-system wide will balk at opening themselves up to competition with Terran miners, in the same way that domestic manufacturers balk at lowering tariffs on foreign imports. Detractors will argue that Solcoin is merely a ploy by perfidious Terran miners to interfere in the money and politics of the other worlds, a sign of an empire in decline, unwilling to gracefully cede interplanetary space to those who dwell there.

A Million Tiny Worlds

But Terran miners won’t be the only Solcoin supporters. To find others, we must turn our attention to the literal fringes of interplanetary society.

Not all humans will choose to live on or near planetary bodies. Many will prefer to take up residence in engineered space habitats that offer the most Earth-like living conditions away from the hustle and grime of Earth itself. Spinning cylinders can provide Earth-equivalent gravity, which is much more difficult to produce on the surface of Mars or the Moon. Fusion lamps, powered by water, can provide Earth-natural sunlight. Space habitats can thrive anywhere. Some may even migrate.

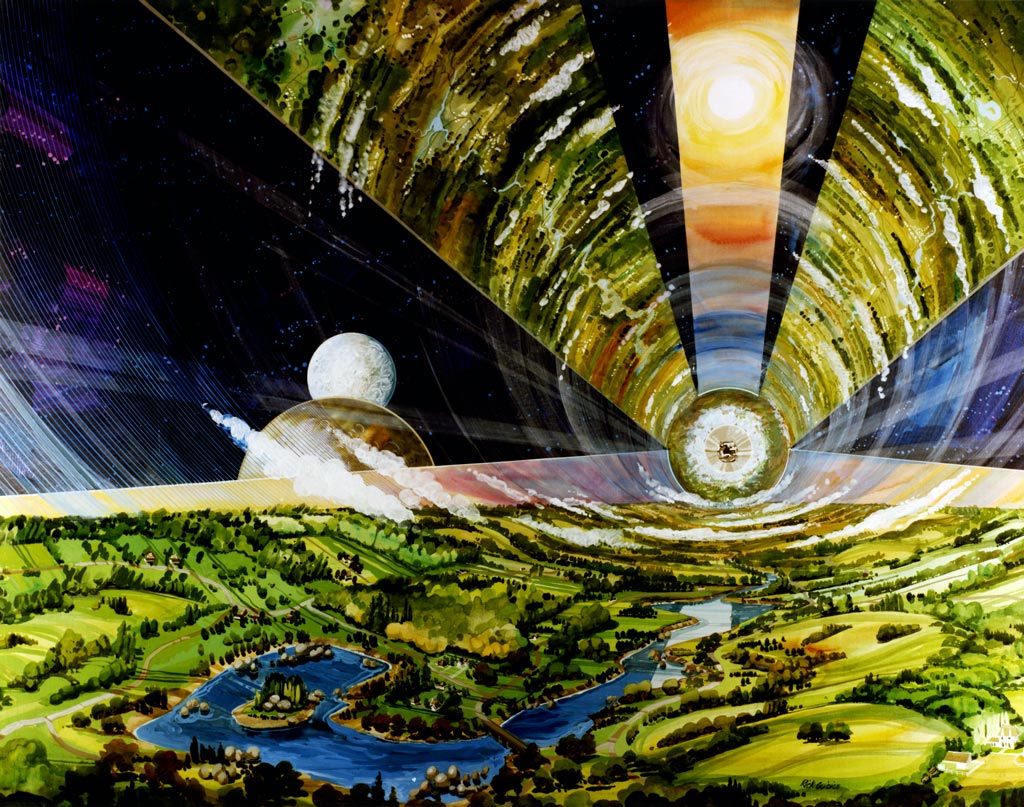

Artificial space colonies can house millions of people and orbit anywhere in the solar system. How will the builders of these bauble worlds participate in the mining industry? [Source]

These habitats will first be built in orbit near the Earth, Moon, and Mars, and then at nearby Lagrange points. But hauling large amounts of material up from a planet’s surface is inefficient and expensive. Later habitats will be built where the materials to make them are abundant and where there is no gravity well to fight: the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, and the belt of comets beyond the orbit of Neptune known as the Kuiper belt (of which Pluto is the most prominent member). Asteroids and comets are made of carbon, silicon, metals, ammonia, methane and water: all raw ingredients of the space industry. They are the perfect substrate for building colonies. The belts will become full with them.

It is possible that belters on opposite sides of the solar system feel no mutual relation, but it’s also possible that the belters have their own cultural identity and economic network full of people with a shared history and similar problems. Belters will want to unite behind a blockchain they can all mine, pulling the virtuous cycle of mining into their orbit.

But a settled belt is very different than a planet. A single space colony may house a few million people, about the scale of a large city. The billions of humans eventually settling the asteroid and Kuiper belts will be spread across hundreds and then thousands of such colonies. At first the colonies may be near each other, but over time they will distribute around the full circumference of the belts. If belters were to start a blockchain, what block time should they choose?

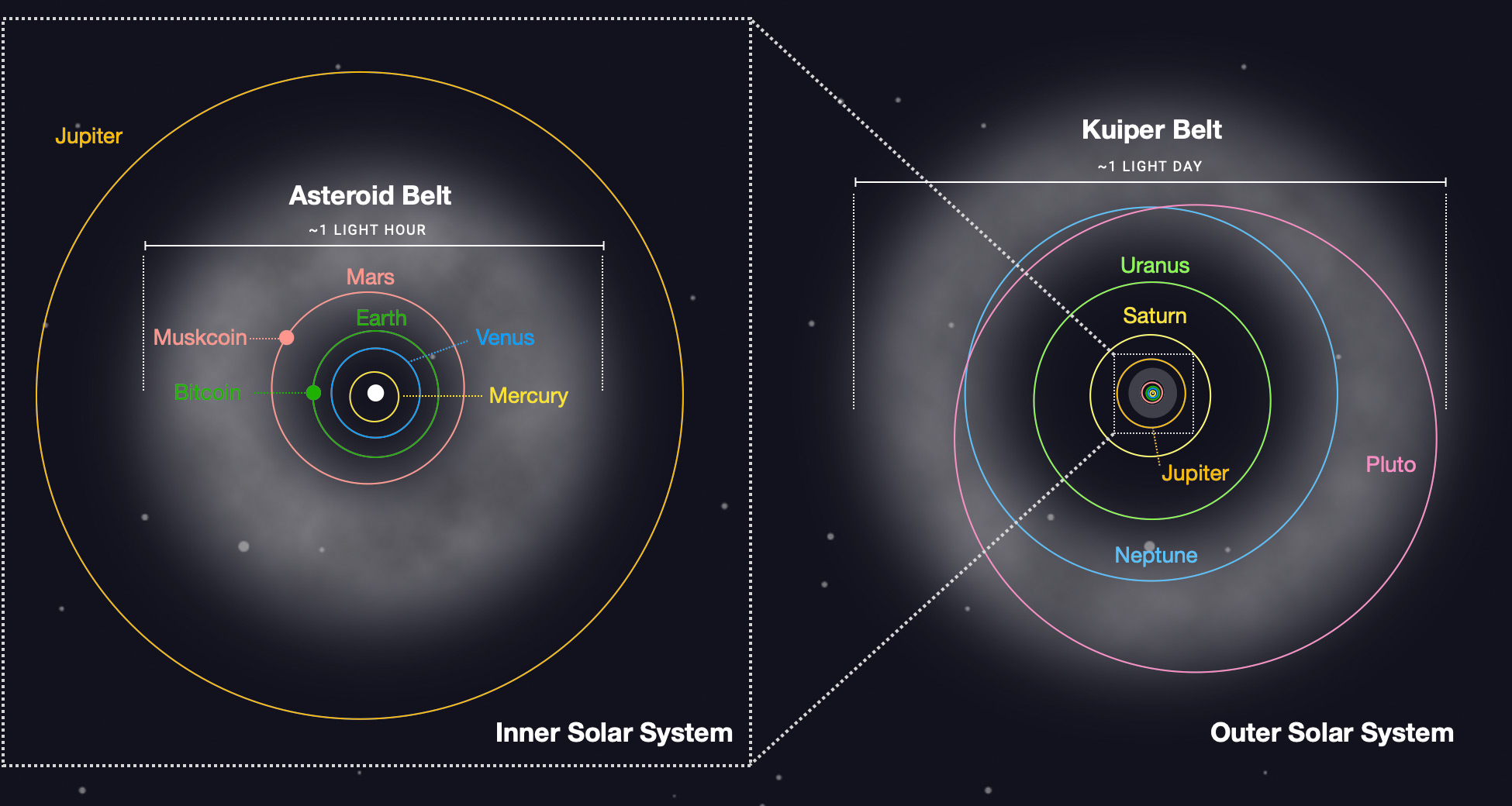

Belts are extended objects which span significant distances in space. The asteroid belt (left), between Mars and Jupiter, is about a light-hour in diameter. The Kuiper belt (right), beyond the orbit of Neptune, is a full light-day in diameter. Type I blockchains with block times of minutes can be used by belters but will never be mined by them. The huge amounts of energy available in the belts will only be harnessed by a Type II blockchain with a block time comparable to (or, more likely, many times) their diameter.

Planetary blockchains such as bitcoin and Muskcoin have short block times of ~10 minutes and correspondingly small hash horizons. This is sufficient for civilizations such as Earth’s or Mars’, which are located near planets and span just a few light-seconds. If, like these planetary blockchains, belters choose a convenient time near 10 minutes, then their hash horizons will be similarly small. Asteroids in the asteroid belt aren’t a dangerous mine-field of obstacles, as often depicted in movies. In reality, asteroids are about 3 light-seconds apart on average, more than twice as far apart as the Earth and Moon. Comets in the Kuiper belt are even further apart. A blockchain with a small hash horizon will therefore only be able to connect miners on a few nearby colonies. A small number of nearby colonies is like a small number of nearby cities. They will not have the population, industry, or hashrate to support an entire blockchain, let alone one that could defend itself against aggression from nearby planetary blockchains. But the population of the full belt, hashing together, could hold against the center.

The geography, or perhaps the topology, of their society presents some immediate challenges. A belt is not localized near any single point. It is an annulus of material surrounding the Sun. The diameter of the asteroid belt is larger than the orbit of Mars — signals take almost a full hour to cross it. The Kuiper belt is even larger in diameter– a full light-day. A blockchain that could connect all these far-flung miners would need an extremely long block time.

This is exactly the problem a stellar blockchain such as Solcoin solves. Without Solcoin, belters could transact using any number of local planetary blockchains, but they would never be able start the virtuous cycle of mining. With Solcoin, belters can spin up mining rigs anywhere they can find energy to harvest and hope to earn transaction fees from solar-system wide trade.

Perhaps one of the great ironies of the future will be the Solcoin alliance between urbane Terrans and hillbilly belters.

Type I & II Blockchains Are Different

Though they work on the same principles, the vast difference in scale between stellar Type II and planetary Type I blockchains doesn’t just make Solcoin bigger, it makes it different.

Confirmation times are long

To allow mining across the solar system, Solcoin must have a hash horizon that is 1-2 light days wide, but this does not necessarily mean the block time should be equal to 1-2 days. It only takes a few seconds for a signal to traverse the entire Earth’s network infrastructure, yet the bitcoin block time is ten minutes, which is hundreds of times longer.

The unpredictability of proof-of-work means that block times have irreducible statistical variance — a blockchain targeting a block time of ten minutes will occasionally have blocks just a few minutes or even seconds apart. The block time needs to be long enough that the network has enough time to integrate over the current fee market in the mempool, as well as source enough hashrate to defend against adversarial attempts to reorg the chain. Block times should be at least several times the signal traversal time between the most distant miners.

If we naively scaled up the numbers, a signal traversal time of 1-2 days across the settled solar system suggests a block time of several hundred days. Linear scaling may be too conservative; it’s possible that as signal traversal times increase, the ideal multiple for block time may decrease. We might be less conservative and suggest a block time as short as 7-30 days — between a Terran standard week and month — but even in this optimistic case, a single Solcoin transaction could take_months_ to confirm!

Issuance is slow

If Solcoin’s monetary policy is comparable to bitcoin’s (fixed cap, block subsidy, halvings), then the long block time implies a correspondingly slow issuance schedule. Assuming the halving period is kept at 210,000 blocks, instead of every four years, 7-30 day blocks would imply that halvings occur every ~4,000 – 17,000 years. Bitcoin is scheduled to produce its predetermined supply of 21M BTC within ~140 years of launch. With 7-30 day blocks, Solcoin would take ~140,000 – 600,000 years to do the same . These are longer timescales than humanity has ever considered — longer, perhaps, than the history of our species itself.

Solcoin’s issuance could be accelerated by restricting its scale in space. If the poor denizens of the Kuiper belt can be excluded, then the required hash horizon of Solcoin can be reduced to, say, the diameter of Neptune’s orbit: a mere 8 light-hours. This would enable a correspondingly shorter block time, which leads to more frequent halvings. Alternatively, Solcoin could retain its desired scale in space and the corresponding 7-30 day block time but simply reduce the number of blocks between each halvings from 210,000 to perhaps as low as 10,000. This still yields ~180 – 800 years between halvings and ~6,600 – 29,000 years to produce the Solcoin supply.

It seems that regardless of what numbers we use, if we want Solcoin mining to be possible over an appreciable fraction of our solar system, then we are forced to think at very long time scales.

Difficulty & hashrate are high

As a stellar blockchain, Solcoin’s miners should not be concentrated too densely near any particular planet or colony. This means the difficulty of Solcoin blocks has to be extremely high.

During the early days of Solcoin’s launch, when hashrate is low, if minimum difficulty were also low, then it would be possible for miners who command significant hashrate in one location (a single planet) to mine blocks faster than they can be transmitted through the network (1-2 days). If more than one miner (or pool) did this, it would destabilize consensus. Difficulty should therefore be high enough that even if a significant percentage of some planet’s hashrate chooses to mine Solcoin, it would be insufficient to consistently win them blocks.

One strategy Solcoin might use to rebuff attacks from miners of planetary blockchains during its infancy is to use a unique mining algorithm. While this may initially work, it’s also possible that future advances make printing custom ASICs trivial. The surer defense is to simply set a high difficulty and not launch Solcoin until sufficient hashrate exists to operate it. Using the same mining algorithm as planetary blockchains may also be a way to encourage adoption.

To stabilize payouts in the face of such high difficulties (and long block times), Solcoin miners would be forced to create and join mining pools distributed across the solar system. (Note: Even if Solcoin hashrate grows to exceed that of planetary blockchains, by the First Law, distributed Solcoin mining pools cannot coordinate to attack planetary blockchains as most of their members would be outside a planetary blockchain’s hash horizon.)

Energy usage & price are astronomical

Because of its high difficulty, the proof-of-work in a single Solcoin block will eventually represent more energy than that used by whole planets. Solcoin isn’t just a stellar blockchain in physical diameter, it’s also a stellar blockchain in energy scale (we’ll return to this point below).

For mining to make economic sense, Solcoins must therefore become extremely valuable (in planetary currency). This hypothesis will fuel much early speculation in the Solcoin price. But speculators alone aren’t sufficient to sustain a gargantuan project such as Solcoin. If Solcoin is to succeed, it must be broadly accepted by interplanetary society. Given that Solcoin’s price and pace rule out many kinds of economic activity, what exactly would people use it for? Why would people, outside of greedy Terrans and poor belters, want to hold Solcoin?

Type I & II Civilizations are Different

Type II civilizations are as different from Type I civilizations as Type II blockchains are from Type I blockchains. As a Type I civilization evolves into a Type II, it experiences structural changes paralleled by its money. Both become lower time-preference, have longer investment horizons, and increased energy requirements. Civilizations and blockchains coevolve together.

Let’s explore some of the ways Type I & II civilizations differ, and in so doing, understand why a Type II civilization will find a Type II blockchain such as Solcoin valuable.

Culture is low time-preference

Like today’s time zone differences, the myriad day and night cycles across the solar system will make coordinating simultaneous interplanetary activities more difficult. But unlike communicating across time zones, interplanetary communication is asynchronous. When you call someone on the opposite side of the world, it may be an inconvenient time for them, but your conversation starts instantly and occurs in real-time. You don’t call someone on a different planet at all; you send them recorded messages which they receive hours later. This is an unavoidable limitation of communication imposed upon on all future civilizations by the finite speed of light.

Asynchronous communication is already commonplace in our world today — everyone emails, texts, and messages on social platforms, but live connections are important to us. Remote work and relationships are maintained through the ease of getting “online” (witness the massive increase video chat applications during the 2020 pandemic). When major parts of our civilization are incapable of live communication, the future begins to resemble the past — a slower-paced society of letters and telegrams.

But the future will also resemble no time before it. Technology, whether through medicine, computing, or both, will significantly extend human lifespans. A life expectancy of hundreds or even thousands of years may become commonplace. Long-lived, asynchronously communicating people will have a different relationship to time than humans of today. The cumulative effect of these changing temporal relationships across society, even if life extension is somewhat rare, could be profound. Patience, planning, and low time-preference — at least compared with today’s business cycles — may become the norm.

For a person who expects to live for 10,000 years and is accustomed to casual conversations bridging hours and days of light lag, the slowness of Solcoin may be unremarkable. Waiting three months for a Solcoin transaction to confirm may feel normal, just like waiting an hour for a bitcoin transaction to confirm feels normal today. Waiting a century for a time-locked Solcoin contract to activate would be like waiting just a year today for long-term capital gains to kick in. Solcoin’s pace increasingly matches the time-preference of its era.

Transportation is slow

Modern transportation networks make our world feel small. Voyages between distant worlds will take months and be expensive. This will cause interplanetary travel to become highly stratified by time-preference.

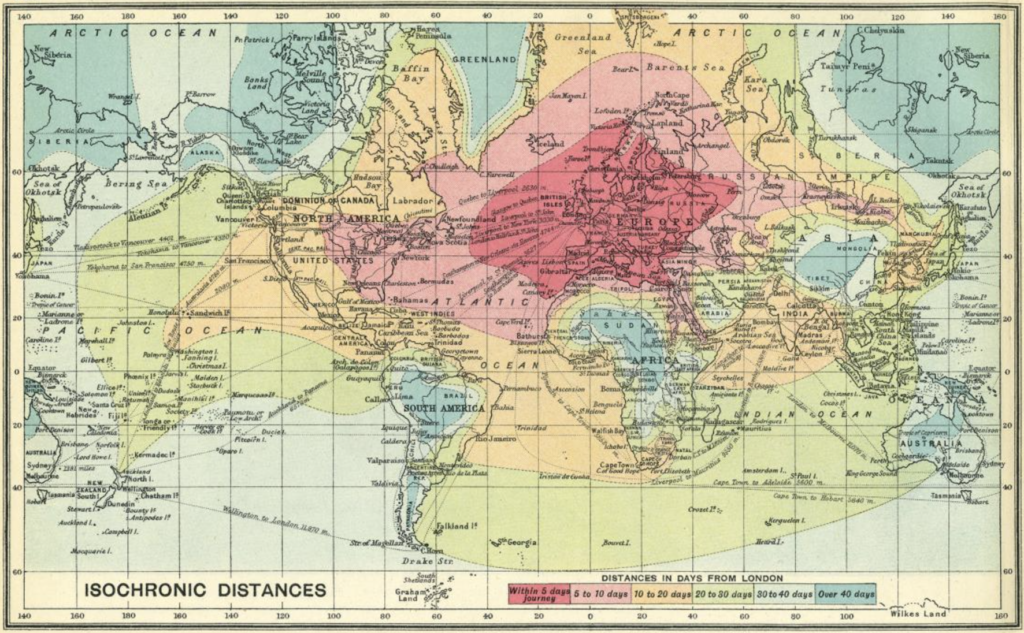

Isochrone map of distances from London, circa 1843. Anywhere in Europe could be reached within a week but it could take months to reach the more far-flung parts of the British Empire. The vast distances of space will similarly require many months to cross. In this way the future will be like the past. (source)

Isochrone map of distances from London, circa 1843. Anywhere in Europe could be reached within a week but it could take months to reach the more far-flung parts of the British Empire. The vast distances of space will similarly require many months to cross. In this way the future will be like the past. (source)

Transporting people or vital supplies will be done along direct, extremely expensive minimum-time routes, which will still take weeks to months, depending on the distance. But most goods will be shipped along slower, cheaper minimum-energy routes, which like the seasonal oceanic shipping routes of the past, are only sporadically available, varying with the positions of the planets in their orbits. The Hohmann transfer from Earth to Mars, for example, is one of the most energy-efficient routes between those planets but takes 9 months to complete and only presents a launch window every 24 months. Martian businesses may become accustomed to waiting up to 3 years for the next cheap delivery window from Earth.

There are even more energy efficient trajectories between worlds (utilizing the Interplanetary Transport Network) that take decades or centuries. These routes are usually ignored as too long to be practical, but they may be appropriate for transporting huge amounts of mass such as whole asteroids and comets. A significant source of revenue for belters may be the export of such objects from their home orbit to the rest of the solar system. The cheapest way to ship a 5-mile diameter water-rich comet to your Jovian orbital factory might be to pay up-front in Solcoin and wait 75 years.

Investment horizons are long

“Meths” in Netflix’s Altered Carbon series are immortal oligarchs commanding vast power and wealth. They can afford unlimited backups of their own bodies and can spend decades traveling between star systems. How would such a person store their wealth?

Longer lives don’t just mean that we can be more patient with Solcoin transactions, they change the way we invest and our risk/return tolerance. If you plan to live for 10,000 years, how would you store and preserve your wealth?

Wealth preservation is all about risk management, and the future, on a long enough time scale, is a dangerous place. You might not worry today about a catastrophic “black swan” event with a 1% chance of occurring per century, but if you lived for 10,000 years, the probability of that same event occurring at least once approaches 2-in-3. Given enough time, natural accidents like extraterrestrial impacts, solar flares, or super-volcanoes will manifest somewhere, sometime.

And given our bellicose history, it’s unlikely that future societies expanding and competing for the solar system’s resources will always remain at peace; total war in a high-energy future society could mean the destruction of an entire planet and its blockchain along with it. Even if the conflict doesn’t escalate to such a destructive level, if Earth and Mars were to go to war, could either bitcoin or Muskcoin be considered neutral money? Would bitcoin miners, united by their common location on Earth to view Mars as an enemy, choose (or be politically compelled) to censor the transactions of known Martian entities? This possibility was one of the instigating causes of the Muskcoin revolution, after all. If you are a rich Martian pondering going into cryo-stasis for 1,000 years as you await the development of your investments, you may worry about these kinds of unforeseen political conflicts.

Long time horizon investors today use real estate or commodities such as gold, oil, precious metals and — increasingly — bitcoin to hedge exposure to geopolitical risk. What assets would long time horizon investors of the future use to hedge their exposure to heliopolitical risk?

Planetary blockchains are, by definition, localized to a given planet and are therefore inseparable from the heliopolitical risks of that planet. Investors of the future can attempt to hedge this risk by holding a portfolio of planetary blockchains and rebalancing it over the centuries, or they may invest in commodities, though their choices would be different (e.g. hydrogen instead of petroleum).

By distributing consensus throughout the whole solar system, a stellar blockchain such as Solcoin provides exactly the asset that long time horizon investors are looking for. They view Solcoin’s long block times and tremendous hashrates as features, not bugs. Solcoin is a heliopolitically neutral, low-risk money for long-term capital preservation.

This will not be apparent to elites when Solcoin first launches. “Serious” money managers will not initially consider Solcoin a real asset class, but significant appreciation over some decades (or centuries) may convince them that Solcoin has superior properties as a store of wealth compared to any planetary blockchain, due to its greater robustness against local threats — natural or political. Eventually, Solcoin will be held by everyone, whether directly or through some future equivalent of an index fund.

Energy scales are increasing

Science fiction often depicts interplanetary societies launching interstellar missions or constructing megastructures, such as ringworlds, Dyson spheres/swarms, Shkadov thrusters, &c., but seldom describes how such projects are funded. Megaprojects will be the most expensive and largest collaborations in the history of our species, consuming more energy than entire planetary societies. They will take thousands of years to complete, which means thousands of years of paying designers, suppliers, & builders from Mercury to the Kuiper belt. What currency will these people and companies demand? Solcoin, of course!

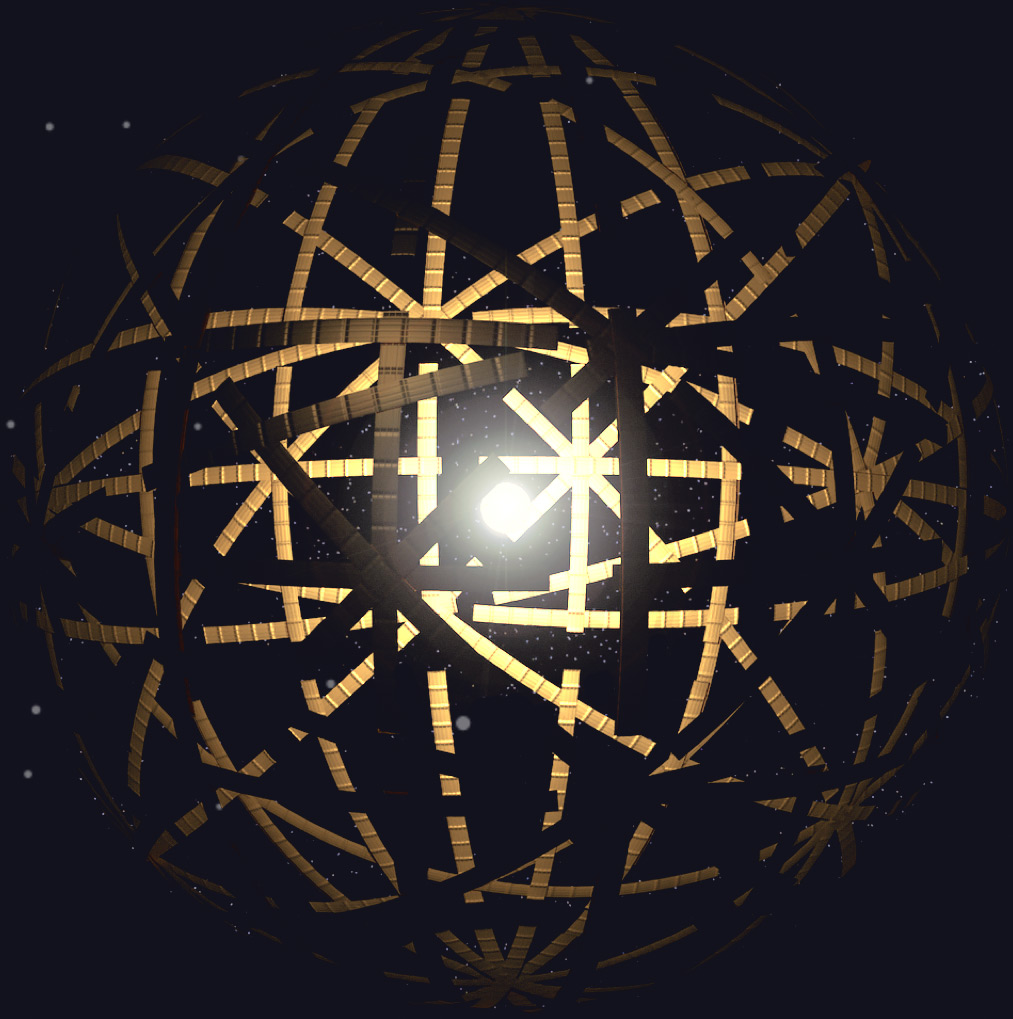

A “Dyson Sphere” is a swarm of spacecraft & colonies harvesting the full energy output of a star. Which markets are hungry enough to consume a star’s worth of energy? [Source]

Solcoin’s heliopolitical neutrality makes it a natural fit for funding megaprojects. Contractors and investors across the solar system feel more comfortable relying on a neutral Solcoin rather than a possibly partisan planetary blockchain such as bitcoin. Solcoin’s timescale also matches that of megaprojects themselves, allowing their supporters to manage the risk of such a large investment over such a long time period. But there is an even deeper connection between Type II blockchains and megaprojects: they both operate at the same tremendously high energy scales.

Consider the classic example of a Dyson sphere (above). The amount of energy required to reconfigure enough matter to blot out a star, by definition, puts such a project in the Type II category. Why would humanity choose to build such a megastructure or use so much energy? A Dyson sphere can support not trillions of people but trillions of Earth’s worth of people. Simple population expansion and uninhibited consumerism alone may not be enough to generate demand for so much energy.

But there are other drivers for energy consumption. Fundamental research and interstellar missions will also require energy scales beyond a single planet. If humanity is to ever experiment on black holes or settle another star, we will require the energy budget of a Type II civilization, even if we never build a Dyson sphere. This requires creating an economic incentive to collect energy across the whole solar system.

Type I blockchains don’t provide this incentive. It’s true that concentrations of energy far from existing centers of hash will attract settlers, grow civilizations, and start their own blockchains, incentivizing energy collection in the vicinity of that planet, moon, or colony. But these Type I blockchains will not be able to incentivize the collection of energy outside their limited hash horizons. Gathering the vast energy in the comets of the Kuiper belt or from the light our sun streams out into every direction in space requires incentivizing energy collection at every point in our solar system.

This is exactly what a Type II blockchain such as Solcoin does. Solcoin’s broad hash horizon means that a miner can reliably turn harvestable energy anywhere in the solar system into profit without having to first transport it close to a planetary blockchain’s center of hash. Like bitcoin before it on Earth, Solcoin’s hashrate market is a ratchet, which cranks society into ever-higher tiers of energy production.

Turning this relationship around, we also see why it’s vital for a Type II civilization to use a Type II blockchain. Type II civilizations use billions of times more energy than Type I civilizations and, consequently, than Type I blockchains. If even a small fraction of this energy were concentrated in one spatial location and turned into hashrate, it could destabilize a local Type I blockchain — just like a hash bomb during the Muskcoin revolution. Only a Type II blockchain operates at energy scales high enough to defend against such attacks.

Type II Blockchains Won’t Displace Type I

One of the earliest lessons of hyperbitcoinization was that only one blockchain — one sound money — can exist. All other monies fail or are subsumed by bitcoin denominated trade. The successful launches of Muskcoin and other planetary blockchains was another lesson: multiple blockchains — multiple sound monies — can coexist, but only if they’re far enough away from each other in space. Solcoin claims to be a blockchain that is close to everyone (its hash horizon spans the solar system). If there can only be one sound money in one place at one time, doesn’t the success of Solcoin require it to displace all planetary blockchains?

Demand exists across time preferences

Some Solcoin-maximalists will believe this, and will therefore view all planetary blockchains as competitive and their supporters as enemies of Solcoin. But the truth is more nuanced. As we’ve seen, Type II blockchains such as Solcoin are extremely different from Type I blockchains. They’re not just larger; they’re also slower, use more energy, and are much more valuable. This difference in scale segregates economic activity by time preference.

Solcoin is designed for long-timescale, high-energy, cross-solar-system trade and projects. Planetary blockchains cannot support these use cases, which is the source of the low time preference demand for Solcoin in the first place.

But economic activity at the scale of planets will mostly continue to use planetary blockchains. In a hyperbitcoinized economy, only the largest transactions are directly put on the blockchain anyway. Planetary economies are already organized in layers, which settle to their local blockchain. Solcoin may come to be used for a small percentage of the most valuable planetary transactions, but most will continue to use planetary currency. Purchasing the quintessential space coffee will still be done using some higher layer payment network settling through the local planetary blockchain.

Higher layer networks settling to Solcoin will also arise. These layers will allow for faster Solcoin transactions, just as they do for planetary blockchains. But these layers won’t be able to bridge the gap between the Solcoin block time and the pace of daily life (opening & closing channels still requires waiting for blocks to confirm, which could take months in Solcoin). Solcoin is just too slow for most kinds of local trade. This means there will always be some demand for the tokens and hashrate of planetary blockchains. Even if you or your company prefers to operate at the ethereal scale of Solcoin, the vendors you buy from or the workers you hire may have different time preferences than you.

Over time, an increasing fraction of economic value and system-wide hashrate may gravitate to Solcoin — but planetary blockchains will survive where they can. Type II civilizations don’t displace Type I civilizations, they contain them. Similarly, Type II blockchains don’t displace Type I blockchains, they contain them.

Portfolio Management at the Kardashev Scale

One of the important roles of any blockchain is to provide a long-term store of value. Solcoin is designed to be a better store-of-value than any planetary blockchain, so some amount of savings will transfer from planetary blockchains to Solcoin. Investors will decide how much of their portfolio to store in planetary blockchains (they may decide to hold more than one) and how much to store in Solcoin based on their time preference and their heliopolitical concerns. The longer the time horizon of an investor, the more likely they are to hold their wealth in Solcoin, but the need to make investments or purchases on a planetary scale will always ensure some demand for holding planetary blockchains.

As a result, miners will have to decide how much hashrate to invest into their local planetary blockchain (bitcoin, Muskcoin, &c.) vs. how much to invest in Solcoin. The ratio each miner chooses between these two hashrates balances their beliefs about the current hashrate markets, future price movement between Solcoin and their local currency, as well as their own time preference. Miners who value immediate returns will put more hashrate towards their planetary blockchain, those who can afford to be lower time-preference will put more hashrate towards Solcoin. If too many miners in one location are hashing Solcoin, it should create an incentive for others to begin hashing on their local planetary blockchain — and vice versa. To a first approximation, the ratio of hashrate a miner dedicates to their own planetary blockchain vs. to Solcoin should equal the overall hashrate ratio between that planetary blockchain and Solcoin.

Towards a Second Law

Type I & II blockchains can “overlap” in space because the market segregates their usage by time. A physical analogy may help visualize this situation as well as provide some useful terminology.

Interference

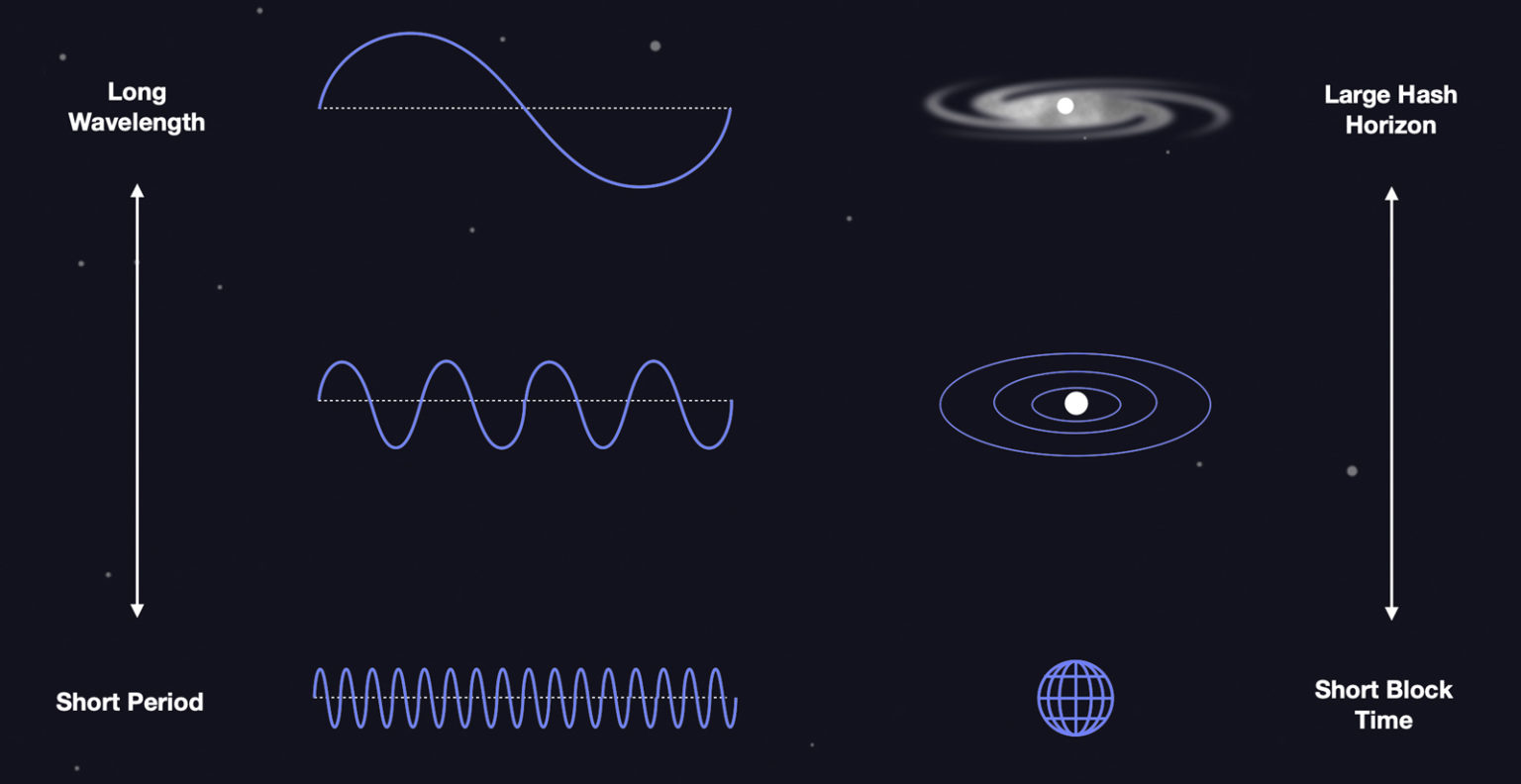

Waves are self-sustaining oscillations that contain or transport energy. Waves are characterized by several parameters such as frequency, wavelength, amplitude, &c. These parameters are constrained: lower the frequency and the wavelength increases while the energy decreases. Interactions between waves can be very rich. When waves have different frequencies/wavelengths, they can overlap in space — one wave will “pass through” another without either being disturbed. When waves have similar frequencies/wavelengths, they can interact strongly, exhibiting constructive or deconstructive interference.

Blockchains aren’t waves, but they are self-sustaining. They contain energy, and they’re characterized by constrained parameters. Instead of a frequency, a blockchain has a block time. Instead of a wavelength, it has a hash horizon. Lower the frequency (block time) and the wavelength (hash horizon) increases (due to the First Law). Interestingly, as we saw above, lowering the frequency increases the energy — Solcoin uses much more energy than a planetary blockchain.

We can use this analogy to talk about blockchains in a new way. Two blockchains with very different frequencies/wavelengths (block times/hash horizons) such as Solcoin and bitcoin can overlap. They don’t “economically interfere” with each other because they operate at such different timescales. The market can support both blockchains for their different use cases.

Two blockchains of similar frequency/wavelength (block time/hash horizon) cannot overlap. They economically interfere with each other: miners and users will inevitably pick one of them. This is why altcoins died out while bitcoin survived. Blockchains of a similar frequency/wavelength must be widely separated, such as bitcoin and Muskcoin, decoupling their mining markets through the First Law.

Summarizing, blockchains can coexist if they are widely separated in physical space OR in frequency space — block time. Type I blockchains have similar block times but are far apart in space. Type I and Type II blockchains overlap in space but are far apart in frequency space — block time.

Resonance

But exactly how widely separated must blockchains be? This is another way waves provide a good analogy.

Waves in free-space (called “traveling waves”) can have any wavelength — this is why you can see light in all colors, but waves interacting with matter will react to it. Most waves will bounce off or decay. Some waves, called “standing waves” or “normal modes,” are special — they can persist for long times, storing or absorbing energy. Normal modes have “characteristic wavelengths” and “natural frequencies,” which are determined by the geometry of the matter they interact with. Normal modes can also “resonate,” quickly absorbing energy input at their characteristic frequencies. This is why no matter how you ring a bell, bang a gong, or pluck a guitar string (within reason), the same tone emerges.

Consider a blockchain with a block time of several hours designed to connect the inner planets — a Type 1.3 blockchain, say. Its block time would be long enough to make Type I transactions expensive and inefficient, yet not long enough to provide Type II risk-management capabilities. Its hash horizon would be smaller than a Type II blockchain, insufficient to include the outer planets and the belts, leaving them without a chain to mine on, dis-incentivizing the collection of energy from their orbits. Such an intermediate, Type 1.x blockchain is an awkward, partial solution.

If blockchains are like waves, then Type I & II blockchains are normal modes. Their characteristic wavelengths and natural frequencies are determined by the distributions of matter they draw energy from and the cultural timescales of the civilizations they power. Type I and II blockchains are Schelling points, resonating with the market, allowing a small group of initial supporters and low hashrate to excite a self-sustaining money that absorbs energy and value.

A Type I blockchain resonates with a 10-minute frequency around a planet or colony and is used for daily transactions and global trade.

A Type II blockchain resonates with a month-long frequency throughout a star system and is used for long-timescale capital preservation and high-energy investments such as megaprojects.

This is why we did not speculate about any blockchains intermediate in scale between Type I and Type II. We hypothesize that intermediate blockchains, should they be launched, would not be Schelling points. Far from resonance, they would decay away, surrendering their hashrate to either Type I or Type II neighbors.

Exclusion

The two analogies of interference and resonance imply a third.

Classical physics is usually continuous. Distinct energy or position states of matter can be arbitrarily close together. Quantum physics is usually discrete. Matter particles must occupy distinct states with different energies and or positions. States are usually “filled up” by matter particles in order of increasing energy, outward from some source. This is known as the Pauli exclusion principle.

Blockchains must resonate around matter distributions (planet or solar systems) and a cultural timescale (real-time or long-term), which means the set of allowable states for blockchains is discrete, not continuous. Blockchains in the same state (location and block time) economically interfere. Like matter particles, only a single blockchain can occupy a given state, and states are populated in order of increasing energy scale and distance from Earth: Type I before Type II, bitcoin before Muskcoin.

We hypothesize blockchains, like matter, obey some economic version of an exclusion principle which we promote as a Second Law:

The Second Law of Bitcoin Astronomy (The Hash Exclusion Principle): Discrete physical and temporal scales provide hierarchical states for blockchains to occupy in order of increasing energy and distance from Earth.

As humanity ascends the Kardashev scale, the Second Law describes how blockchains populate the matter our society has colonized and the timescales our culture can experience.

Blockchains are a kind of economic dark matter, shadowing normal matter wherever civilization settles, invisible but detectable through the constant pressure they exert on energy markets and supply chains.

Type II Civilizations Launch Type III Blockchains

Following the implications of the Second Law, humanity — should we survive long enough — will eventually launch a Type III galactic blockchain.

Such a heady notion requires us to first become a Type 2.x civilization which in turn requires expanding to other stars.

Interstellar missions are Type II megaprojects

Stars are extremely far apart; today’s fastest space probes will take hundreds of thousands of years to reach neighboring stars. Reducing the timeframe of such voyages to centuries or decades will require ships to travel at substantial fractions of the speed of light. Our current generation of spacecraft are also uncrewed and no bigger than cars or small buses; an interstellar mission would require a massive ship capable of supporting a human crew and some complement of (perhaps hibernating) colonists and their supplies.

More mass moving faster means the ship has more kinetic energy. The total amount of kinetic energy can be used to estimate the total cost of the mission (this estimate is an order-of-magnitude lower-bound: construction costs, inefficiencies, and many other considerations make an interstellar mission even more costly in reality). As a concrete example, consider a spaceship the size of a modern aircraft carrier moving at 10% the speed of light (such a ship would still take a century to reach even the closest stars and would barely be big enough to keep its passengers alive en route, but no matter). The kinetic energy of this ship would be orders of magnitude larger than the current annual energy usage of our entire civilization!

And that is just one ship! Launching many interstellar missions will use orders of magnitude more energy than even this. Interstellar settlement is the domain of Type II civilizations. Developing energy infrastructure on such a scale will require markets like Solcoin. If you believe humanity’s destiny is to settle other star systems then you would be a Solcoin supporter.

The cycle repeats anew

Given the years it will take to send transactions, colonists of a remote star system will barely be able to use, much less mine, any Type I blockchains such as bitcoin from our solar system. These colonists will therefore launch their own Type I blockchain to support the first colony at the new star. They may wait to start this blockchain until they arrive in the new system, but they may also start it en route, on the colony ship, or perhaps even prior to launch. As long as all the miners stay with the ship, travel together to the new star system, while continuously hashing, the blockchain — like an ember in a fire bundle — will survive the long, cold journey through interstellar space.

Over thousands of years, the colony will grow, settling other planets of the remote star system, launching additional planetary blockchains. One day there will be sufficient demand at the remote colony to launch its own Type II blockchain. Receiving genesis blocks from human colonies around other stars will make humans here in orbit around Sol feel the fierce pride of parents watching their children grown up.

The cycle grows larger

As humanity grows from a Type II to a Type III civilization, the virtuous cycle will repeat itself on an even larger and more dizzying scale.

Great chains have little chains within their hash horizons,

And little chains have lesser chains, and so ad infinitum.

– Hymenoptera, from MICHAELUS de Saylor’s A Blockchain of Paradoxes (2194)

Our stellar neighborhood will eventually host many Type II blockchains from Solcoin to Centauricoin, Siriuscoin and others. The humans — though they may increasingly not resemble the humans of today — living in orbit of these faraway stars will eventually seek to create the next blockchain on the Kardashev scale, a Type III galactic blockchain with a block time of thousands of years, designed to span our stellar diaspora the way Solcoin spans our solar system and bitcoin or Muskcoin span Earth or Mars.

This galactic blockchain would harvest the energy of unsettled star systems, rogue planets, and interstellar gas clouds. It would have a hashrate larger than the total energy usage of entire Type II civilizations. Over millions of years, it would slowly mint its fixed supply of coins, blithely robust to the occasional nova or rogue black hole.

HODL on.

Part III: Beyond Humanity

So far we have confined our speculations to the human species. But, having come this far, there is no reason we should stop. Should other intelligent civilizations exist in our galaxy, will they also discover blockchains? Will their future societies resemble ours, organized into planetary, stellar, and galactic blockchains? Will blockchains of different species ever interact?

If so, what will happen to our hyperbitcoinized future humans when they detect an indisputably intelligent extraterrestrial transmission which consists of … block headers?

If you enjoyed this article, read Part III here!

THANK YOU

Thank you so much to my wonderful colleagues at Unchained Capital for having the patience to tolerate my speculations and for providing me a platform through which to publish them. Also to be thanked are my friends Brandon Hudgeons, Brandon Quittem, Destry Saul, Joe Kelly, and Taylor Pearson, all of whom provided extended and valuable feedback on early drafts. Particular thanks are due to Martin Grogono who makes everything he touches pretty and Phil Geiger, whose enthusiasm is the second infinite resource in the universe.