All 21 Million Bitcoin Already Exist

| If you find WORDS helpful, Bitcoin donations are unnecessary but appreciated. Our goal is to spread and preserve Bitcoin writings for future generations. Read more. | Make a Donation |

All 21 Million Bitcoin Already Exist

By Phil Geiger

Posted October 25, 2019

“Every piece of money is owned by one of the members of the market economy. The transfer of money from the control of one actor into that of another is temporally immediate and continuous.” -Ludwig Von Mises, Human Action

To celebrate the 600,000th bitcoin block, which has unlocked the 18 millionth bitcoin, and in an effort to become increasingly fun to be around at parties, I’m writing this exploration of the idea that all 21 million bitcoin already exist. This may seem like a semantic or esoteric argument, but bitcoin is truly a different beast, which requires closely evaluating the assumptions we make and the language we use when describing it. By more clearly defining bitcoin and how it functions, we can speak more accurately about its monetization process, which ultimately will help HODLers spread the word to our precoiner friends and family. We are alive for, and witnessing, the greatest event in the history of economics – the rapid monetization of a scarce, apolitical, global currency. Providing our communities with an early competitive edge could have positive long-term implications if bitcoin survives.

Misnomers already run rampant in bitcoin, such as the terms wallets, addresses, and mining. A bitcoin wallet is more closely related to a key ring, or a public and private key generation/coordination factory. Bitcoin addresses aren’t really locations that we want users to repeatedly visit, unlike physical addresses or email addresses. Mining is a similarly incorrect term. This is where I believe much of the confusion arises when evaluating bitcoin, and is where much of the FUD surrounding bitcoin focuses time and energy because it’s easy to misrepresent and is extremely confusing to newcomers.

There are a few questions and assumptions that we will need to explore in order to understand whether all 21 million bitcoin already exist. Is it possible for a computer program to HODL BTC? What are the different inputs required to make a bitcoin transaction? Why would people choose one transaction method vs another? When did all 21 million bitcoin exist? What’s the difference between the available vs unavailable supply? First, we need to understand what is unique about bitcoin’s supply compared to the supply of another “hard currency.” Let’s start by comparing bitcoin to another monetary good: gold.

Bitcoin’s supply vs gold’s supply

It’s most accurate for us to say, based on what we currently understand about physics and the elements, a majority of the supply of gold (AU) in the universe already exists, with nuclear fusion producing some additional supply over time.

The crucial difference between the supply of gold and bitcoin ultimately comes down to what people are capable of knowing about the supply. Due to the expansion of the universe and the universal speed limit, lightspeed, humans have no way of estimating the total supply of gold, since its location is unknown and it’s likely that a majority of the supply is very far away.

On the other hand, we have extremely strong social and technical consensus surrounding bitcoin’s total supply, as well as the exact current location of the locked supply. In fact, we have more information about the BTC stored in upcoming blocks than we do about the currently unlocked supply stored in the blockchain. We know exactly how many BTC will move as a function of the coinbase transaction of discovered blocks, yet we have no way of knowing if a person currently holding, say a million bitcoin, is going to broadcast a transaction in a given moment to convert all of their BTC to another currency.

Bitcoin are unlocked on a set supply schedule that auto-corrects itself via a difficulty adjustment every 2016 blocks in order to maintain the schedule. This allows us to know with extremely high levels of certainty exactly where the currently locked 3 million bitcoin live (block number), and with slightly less, although still extremely precise knowledge about when they will be available for spending by private key (on average every 10 minutes). The difficulty adjustment is the feature that harnesses individual incentives to perpetuate bitcoin’s own growth. By aligning difficulty to network size, it thwarts people’s effort to create more supply and instead uses their effort to increase security of the network.

Theoretically, we can know where all of the gold on Earth is located, but we have no way of knowing precisely when we can get to it, the cost to extract it, or precisely how much gold exists beyond Earth. As such, we can make the assumption that if gold ever becomes valuable enough, we can and will find a way to uncover more of it for use, either by mining on-planet or off-planet, or by harnessing nuclear fusion to create more. This is the nature of supply and demand. If demand for any good or service becomes high enough, it increases the incentives for people to go out and produce more supply.

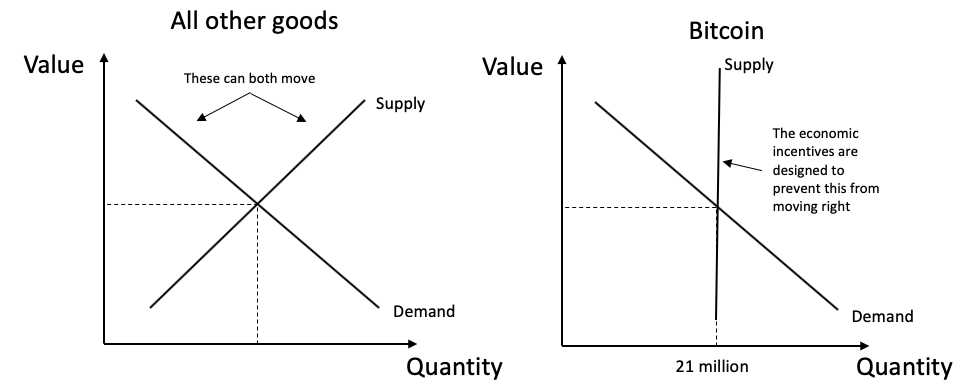

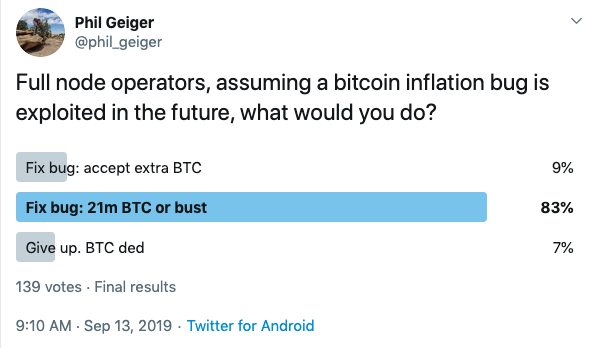

The bitcoin network itself is its 21 million supply. The supply is a vertical line in the supply and demand model, meaning it’s completely inelastic. This limit is written into the code that all full node operators choose to run, and more importantly, it’s the limit we all agree to when we purchase our first bitcoin – it has nearly unanimous social consensus. In bitcoin’s history, there have already been multiple technical inflation bugs discovered, and one inflation bug exploited, but the network ultimately viewed those transactions as an invalid minority hard fork and maintained the socially understood supply schedule, even though it required node operators to run patched software. It’s reasonable to expect we will see more software bugs like this in the future, and once again the network will have to rely on social consensus. Luckily, the network’s incentives are all designed around socially and technically maintaining this 21 million limit.

Full node operators are pretty convicted about the 21 million limit. The outcome of this poll would be bitcoin competing with a minority coin, obviously to be named “Bitcoin Inflation”

With gold, there is no way for a technical or social consensus to manage supply. There is only the element AU, and there is no way to know when and how it will be mined and accessible for human use with any reasonable amount of precision. In gold’s case, we can use supply based predictive models to measure the future supply. We can’t know how much gold exists in the universe, only that it’s difficult to mine additional supply here on Earth. We can model how quickly we expect the supply of gold to inflate, assuming demand remains relatively steady.

So, then what is bitcoin mining?

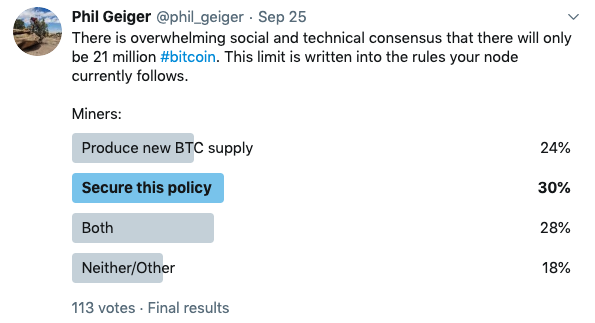

In bitcoin, there are two ways that people are allowed to transact. The first way is what the majority knows and loves, private key authentication. If a person holds a private key associated with a funded address on the blockchain, they are able to move the funds by publicly broadcasting a signature from the private key and including a fee to incentivize the network to purchase electricity and process the transaction. In order to obtain the funded address in the first place, someone somewhere must have expended productive energy to obtain the BTC. The second way that people can transact bitcoin is by selling electricity, in the form of SHA-256 hashes, to the network – what we colloquially (and incorrectly) label as “mining.” By converting the cheapest electricity into as many SHA-256 hashes as possible, these bitcoiners are ordering and proposing batches of pending transactions by finding the valid SHA-256 hash of the block at the current difficulty level. If their ASICs are able to find the solution before others and their proposed blocks are validated by the full nodes according to the rules, “miners” can move the block’s coinbase transaction, often referred to as the miner reward, and the block’s transaction fees to any address they’d like. Do “miners” create new supply in this scenario, or just transact known coinbase transactions and transaction fees by spending electricity in the form of SHA-256 hashes?

We’re pretty split on this. 52% believe miners create supply in some form, 48% believe they do not create supply. There’s a good chance this poll was worded poorly…

We’re pretty split on this. 52% believe miners create supply in some form, 48% believe they do not create supply. There’s a good chance this poll was worded poorly…

It’s a subtle yet important difference that, in my opinion, allows us to say authoritatively that only 21 million bitcoin can possibly exist. The question is (somewhat of) an individual decision that each full node operator and HODLer needs to make. Node operators individually do not get to define what is or isn’t bitcoin, they can only validate whether a bitcoin is a bitcoin, and they individually are either in consensus or out of consensus. That said, when we reach block 630,000 at the next halvening, will your full node accept 12.5 BTC, or will you accept only 6.25? My node will reject any future block that attempts to spend a coinbase transaction that doesn’t follow the supply schedule written in the code my node follows, because this would be an invalid transaction according to the social and technical consensus that I opted into. Through a distributed network of individuals making personal decisions like this, the market ultimately decides what is valid bitcoin, and the market has to date, objectively set bitcoin’s limit to 21 million.

If a computer hashes alone in the woods, does anyone care?

Converting electricity into SHA-256 (or any other algorithm) hashes is an inherently unproductive activity unless it is in the service of something valuable. Converting electricity into hashes for the bitcoin network is productive and profitable because bitcoin holders value using electricity to secure the network, as long as the “miners” abide by the rules of a consensus of HODLers and full node operators.

For individuals interested in selling hashed electricity to the network for the opportunity to transact coinbase funds and transaction fees (mining), there are only a few rules that are absolutely fixed. The most important rule is that there are only 21 million bitcoin. The next rule is that the number of coinbase transaction BTC started at 50 BTC in 2009 and decreases every 210,000 blocks until all 21m BTC can be spent by private keys, in 2140. After that, the hashed electricity purchases the ability to transact only the “transaction fees” paid by users broadcasting private key initiated transactions.

Luckily for “miners,” the difficulty adjustment by design always ensures that it is profitable for someone to sell efficiently hashed electricity to the network. If a given miner is unprofitable long-term, they must make the decision to either shut down their business (and possibly sell their hardware on a secondary market), or to find a cheaper source of electricity. If enough “miners” are unprofitable and shut down their ASICs, causing the network hashrate to drop and blocks to be found on average longer than 10 minutes, the difficulty adjustment recalibrates itself to the new lower hashrate to ensure that the supply schedule average is maintained. As a result, the bitcoin network adjusts itself to always pay market price for electricity converted to hashes depending on the value of the network. If a given “miner” is unprofitable when selling electricity to the bitcoin network, it simply means that they are being outcompeted by other, more efficient “miners.” Given these absolutely rigid network rules, savvy “miners” will quickly recognize that if they can get their electricity costs close to zero, maybe by producing electricity cheaply and choosing whether to sell it for other uses or as hashes to the BTC network, they can effectively sell hashed electricity to the network profitably forever.

It’s the value of the currency, not the number of units

“It must be pointed out that the level of the total stock of money and of the value of the money unit are matters of complete indifference as far as the utility obtained from the use of the money is concerned. Society is always in enjoyment of the maximum utility obtainable from the use of money. Half of the money at the disposal of the community would yield the same utility as the whole stock, even if the variation in the value of the monetary unit was not proportioned to the variation in the stock of money.” -Ludwig Von Mises, The Theory of Money and Credit

After Satoshi found the genesis block and Hal Finney and friends agreed to participate in the network according to the rules set forth in the code and, more importantly, the social consensus, all 21 million bitcoin instantly popped into existence in a “Big Bang” moment. Each early user that converted electricity to hashes to transact early coinbase transactions received private key access to a large number of (at the time valueless) bitcoin as well as the understanding of the rules that future HODLers and “miners” can transact the locked supply of bitcoin by submitting electricity as hashes to compete and solve for blocks of transactions.

In this way, we can look at the value of the locked bitcoin as though it is distributed and held equally by every participant in the network. This value is paid by the HODLers to “miners” for submitting hashed electricity to the network at the market rate, measured by the value of the network it’s spent to protect. In 2009, the bitcoin network was worth very little to just a few people, so the electricity cost to transact 50 BTC of coinbase funds was extremely low. Today, earning the ability to transact 12.5 BTC is worth spending around 100 exahashes of electricity per second.

Everyone who joins the network in any capacity should recognize that roughly 14% (3m/21m) of the value they are purchasing as of October 2019 is held by all participants in the network equally, only to be transacted by individuals submitting valid PoW to order and secure transactions. This has all gone according to the set supply schedule since day 1 of bitcoin, and nothing changes about the economic incentives of selling hashed electricity to the network in the future. The difficulty adjustment, by design, ensures that it is always profitable for the most efficient energy producers to sell their cheapest electricity to the bitcoin network.

It has been posited that machines and software can hold and transact with private keys. I’m positing that we have nearly 11 years of empirical evidence that the network itself has been holding and transacting bitcoin, but instead of with private key signatures, it’s in exchange for hashed electricity.

It’s not the number of BTC that one party or another holds that matters. It’s the value of the overall network that matters, and the value of the network can only grow by understanding that its monetary properties are sound. There are only 21 million bitcoin.

All or nothing

Bitcoin’s innovation is absolute scarcity accessible in a way that is borderless, neutral, and permissionless. This innovation is shockingly disruptive to all facets of human interaction, and it’s this innovation that drives the increase in the value of the network over time. Bitcoin is its 21 million limit. At no time can its supply be anything other than 21 million, because that would go against what we currently know and understand about how the network functions, and would unsolve the problem of “digital scarcity.”

Bitcoin was able to achieve absolute scarcity by its network architecture, which is designed to increase in decentralization over time and to actively reject the human desire to produce more supply of a highly demanded good. Increasing decentralization over time effectively crowdsources the decision of bitcoin’s total supply to the entire network of participants, with the basic assumption that a decentralized network of individuals will not choose to debase their own currency, when each participant does not have access to seigniorage opportunities.

As a result, the prudent full node operator, “miner,” and HODLer can all act under the assumption that the 21 million limit is non-negotiable. The knowledge of this disruption in scarcity is slowly surfacing organically via the free market and through the network of “HODLers of Last Resort,” but this whole experiment depends on the ossified foundation of 21 million with clear, neutral, and unchangeable rules about how people are able to transact.

Because we voluntarily opted into this network, we can say that all 21 million bitcoin already exist today, since the rules the network consensus follows dictate that the supply schedule must be upheld. The only difference between the accessible/inaccessible supply is who or what currently HODLs the value of the coinbase bitcoin, and how humans must compete to transact with either the bitcoin tracked by the blockchain or the bitcoin tracked by the block number behind PoW and the difficulty adjustment.

Digital scarcity is a pretty strange idea. The bitcoin tracked by the blockchain are ultimately just ones and zeros and mathematical functions supported by economic incentives. The same holds true for the coinbase transaction coins. The schedule is written into the software we run, and there can’t be a scenario where an upcoming block contains a different numerical value of coinbase coins because the social and technical consensus does not view that as bitcoin.

Bitcoin is the intersection between code and social consensus. Either all 21 million already exist, or none of them exist. There is no middle ground.

Views presented are expressly my own and not those of Unchained Capital or my colleagues. Thanks to Parker Lewis, Nolan Johnson, and Michael Goldstein for reviewing and for providing valuable feedback.