A Conflict of Crypto Visions

| If you find WORDS helpful, Bitcoin donations are unnecessary but appreciated. Our goal is to spread and preserve Bitcoin writings for future generations. Read more. | Make a Donation |

A Conflict of Crypto Visions

Why do we fight? A framework suggests deeper reasons

By Yassine Elmandjra and Arjun Balaji

Posted January 29, 2019

Conflicts raging within “crypto” are endless. Heated debates take place on a wide spectrum of issues, with little attempt to devise compromises acceptable to both sides. Interestingly, it is the same people who consistently position themselves on opposite sides of these issues. From monetary maximalism and wealth distribution to governance and consensus algorithms, the issues vary tremendously while the formed groups of opposition remain the same. Naturally, this creates an unproductive habit of each side blindly talking past the other.

In A Conflict of Visions and The Vision of the Anointed, political economist and social theorist Thomas Sowell argues that this phenomenon comes from fundamental differences in people’s assumptions about the nature of systems and their limitations. While seldom consciously recognized, these sets of assumptions are the largest drivers influencing people’s opinions. Since visions are rarely examined but have profound impact, Sowell introduces the “conflict of visions” as a mechanism to think about these assumptions.

By highlighting how these assumptions play a fundamental role in shaping our views, we shed light on the “conflict of visions” and ideological battles raging within proponents of cryptocurrencies.

We begin our analysis by laying out the framework of conflicting visions. Using this framework, we proceed to explain the conflict of “crypto” visions. From an understanding of the conflict of crypto visions, we then comment on the structure of arguments taking place within crypto, before diving into the meat of our analysis: an exposition of four episodes exemplifying the conflict of crypto visions.

Setting The Scene

- I. Defining Visions

- II. The Conflict of “Crypto” Visions

- III. The Structure of Arguments

Episodes

- IV. Episode 1: Monetary Maximalism vs. Multicoinery

- V. Episode 2: The “Fairness” of Crypto Distribution

- VI. Episode 3: Governance

- VII. Episode 4: Proof-of-work vs. Proof-of-stake

- VIII. The Future Remains To Be Built

Defining Visions

In order to understand the conflict of “crypto” visions, it is important to first establish what a vision is per Sowell’s work. Simply, a vision is a gut feeling about how things should work — a set of assumptions about the limitations and nature of the world that enables someone to understand (or at least believe to understand) why things work the way they do. Sowell defines two opposing sets of assumptions and assigns them the terms “constrained” and “unconstrained.”

Constrained Vision

At the core of each vision is some strong belief or recognition of limitations. Those with a constrained vision see certain realities as unalterable, “scarcity, self-interest, human fallibility, evil.” [1] Under the constrained vision, the only way to improve is to understand the fundamental laws of nature and the only way to innovate is to remain consistent with the specific parameters set forth by these laws.

The constrained vision realizes that while A may be better than B, it does not matter if A simply cannot be done. For instance, while achieving flight by wishing away gravity or ending war by wishing away violence would be great, it is simply not within the realm of possibilities. Consistent with the constrained vision are concepts like Smith’s Invisible Hand and Zhuangzi’s Spontaneous Order, which recognize the limitations of man and prescribe ideas that transform these limitations into progress.

The constrained vision encourages decision making by identifying tradeoffs rather than solutions. Given the limited options available, the constrained vision attempts to make the best trade-offs with an understanding that “unmet needs” will necessarily remain. As such, “particular solutions to particular problems are far less important than having and maintaining the right processes for making trade-offs and correcting inevitable mistakes.” [2]

Unconstrained Vision

Those with an unconstrained vision believe that the only limitation to achieving a desired outcome is our lack of imagination. Through this lens, the underlying problems in any system exist only because people are not wise, caring, imaginative, or bold enough: with the right mindset, scarcity can be eliminated, man’s self-interest can be corrected, imperfections perfected, and all evil eradicated. Instead of building mechanisms to work around any fundamental limitations, the unconstrained vision sees it possible to re-engineer the world to eliminate its flaws. As such, “intractable problems with painful trade-offs are simply not part of the unconstrained vision.” [3]

The questions posed under the unconstrained vision are centered around how to remove particular negative features in an existing situation to create a solution. By doing so, decision making boils down to choosing the perfect solution instead of identifying tradeoffs. With the right innovation in place, few, if any, sacrifices must be made to achieve a particular improvement. In the unconstrained vision, questions of feasibility are not of primary concern, as trade-offs merely reflect varying scales of preferences and circumstances among individuals.

In both cases, regardless of the assumptions held, the desired outcome remains the same. The goal in both visions is to create the best possible outcome. As these assumptions are so fundamental to decision making, very rarely is there agreement on how to achieve desired outcomes. Both visions acknowledge that the world has unlimited desires and believe there to be an optimal way to accommodate for these desires.

As the labels “constrained” and “unconstrained” suggest, one vision acknowledges that we cannot get everything we want (constrained) and the other affirms our potential to be limitless (unconstrained). It should therefore come as no surprise that each vision reaches opposite conclusions on how to accommodate for a desired outcome.

The Conflict of “Crypto” Visions

With this framing in mind, it is easy to begin to see how many of crypto’s major intellectual fault lines lie along the constrained/unconstrained divide. The space is nascent: a large canvas with a massive surface area for experimentation and tens of thousands of participants, each with their own distinct end game.

In the absence of widespread adoption, participants fall back to narrative. When defining these narratives, we see intra-blockchain divides — is the end vision of “crypto” a hyper-capitalist Galt’s Gulch or a radical markets-inspired disintermediated society (or both)? Even inter-blockchain narratives are inconsistent as we’ve seen narratives around Bitcoin and Ethereum transform over time.

This post builds on prior work from Nic Carter and Hasu exploring Bitcoin’s evolving narratives (and Felipe Pereira’s similar efforts with Ethereum). While researchers have focused on describing how narratives have evolved over time, less analysis has been done to frame these evolutions in context: are these evolutions simply opportunistic, the result of shifting commercial (and investment) opportunity in the cryptocurrency ecosystem, or do they reflect more fundamentally disjointed philosophical orientations?

The most salient distinction people have made, between “money crypto” and “tech crypto”, is a good starting point but incomplete. In our view, these distinctions don’t come down to “Silicon Valley” v. “cypherpunk” — many cypherpunks are not strong advocates of base-layer privacy and many SV entrepreneurs are wary of the “move fast and break things” culture of their peers — these distinctions are more foundational, reflective of constrained and unconstrained views of the future that technologies can help build.

The Structure of Arguments

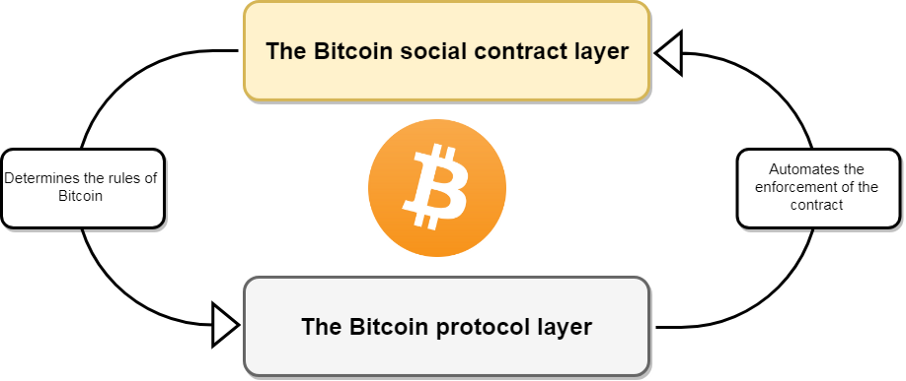

Hasu’s model of Bitcoin’s_ _social contract_ _illustrates the dualistic relationship between the social contract and implementation details in public blockchains.

Hasu’s model of Bitcoin’s_ _social contract_ _illustrates the dualistic relationship between the social contract and implementation details in public blockchains.

Virtually every debate about cryptocurrencies happens at the social layer. This is for good reason, given the nature of the network governance models many public blockchains follow, decisions around consensus often reinforce precedents for the future. As such, design is approached carefully and with thoughtful consideration in some major historical debates:

- Is it possible to have a sustainable long-term security model with a fixed money supply (v. mild or high inflation)?

- How important is programmability and expressiveness considering the increased attack surface and increased security cost?

- Is “absolute” base-layer privacy worthwhile if it increases the difficulty of verification of the money supply (or requires greater trust in the issuers or maintainers of the system)?

- Is increasing the block-size — lowering transaction fees and allowing full node cost to scale up linearly — a short-sighted decision given the uncertainty of future advancements?

These debates are rarely presented as such. Rather than presenting ideas as a question of tradeoffs, discourse — whether in a tiny Telegram chat or on stage at a conference — devolves into religious fervor and ad hominem. Cryptocurrency prices serve as a real-time scoreboard for winning narratives, with ownership creating bias as people “shill their bags” in the face of presenting debates with nuance.

Much of the debate ends up substituting opaque proclamation for arguments. Enthusiasts fall back to simple quips and vacuous rhetoric — technical features that are favored and already exist are “here to stay” while proposed features are “inevitable.” Unpopular existing features are “obsolete” and unpopular, ambitious pitches are “unrealistic.”

To see through this vacuous rhetoric, Sowell suggests applying general principles of common sense (which are nevertheless often ignored) illustrated below:

- All statements are true, if you are free to redefine their terms

- Any statistic can be extrapolated

- A can always exceed B if not all of B is counted or if A is exaggerated

- For every expert there is an equal and opposite expert, but for every fact there is not necessarily an equal and opposite fact.

- Every policy is a success by sufficiently low standards and a failure by sufficiently high standards.

- Most variables can show either an upward trend or a downward trend, depending on the base year chosen.

- You can always create a fraction by putting one variable upstairs and another variable downstairs, but that does not establish any causal relationship between them, nor does the resulting quotient have any necessary relationship to anything in the real world

A careful examination of Sowell’s principles sheds light on the lack of thoughtful consideration that much of “crypto” debate is predicated upon.

Episode I: Monetary Maximalism vs. Multicoinery

First, we only had Bitcoin, released by Satoshi, who by all evidence was likely an outsider to the establishment. As Bitcoin was strictly focused on offering a new electronic cash system without the reliance of a trusted central mint, the utmost focus of enthusiasts and developers has always been security (of the codebase) and security again (of the monetary policy). Historically, changes to Bitcoin have been debated not just on their merits but in their second and third-order effects on security.

The original grassroots cypherpunk movement of Bitcoin was never focused on “blockchain technology”. To this day, the majority of “Bitcoin maximalists” or “shitcoin minimalists” see Bitcoin’s focus as a grassroots bottom-up effort in engineering in stark contrast to the more formal top-down efforts employed by projects like Ethereum, Tezos, and others.

Inspired by the view of Austrian economists, Bitcoiners have historically opted for a “simplistic” & “adversarial” view of the world, grounded in an understanding of monetary history: that the “killer app” is money and that Bitcoin, a potential global money competitor, has the largest potential TAM. In their view, other projects attempting to create a better Bitcoin and iterate on its “fundamental design limitations” misunderstand its intended use.

What Bitcoiners attack with historicism, multi-coiners defend with vision, often criticizing this limited, “simplistic” view held. The unconstrained vision believes it to be “a major failure of imagination (or really just plain observation, frankly) to think that crypto has nothing more to offer than a slow and volatile form of sound money.”

Under these sets of unconstrained assumptions, Bitcoin might instead be described as a part of the “calculator era” of cryptocurrencies, as recently explained by Andreessen Horowitz partner Jesse Walden:

Many argue that that the most important property of a decentralized money system is security, not programmability, and that a limited scripting language is thus a feature, not a bug. Through that lens, we can view Bitcoin as more of a calculator than a computer (and that is intended as a positive remark!). It is purpose built and good at its task, but for developers keen to tinker and build new applications an evolution to a new architecture was required.

To people biased with an unconstrained view of the world, Bitcoin suffers from a lack of vision. As such, the same feature (e.g. complex programmability) might be viewed by the constrained vision as a bug and by the unconstrained vision as a feature. Sowell (135) clarifies this distinction:

To those with the unconstrained the question is: What will remove particular negative features in the existing situation to create a solution? Those with the tragic vision ask: What must be sacrificed to achieve this particular improvement?

On the other hand, to the constrained vision there are no solutions, only trade offs . Bitcoin developers like Jimmy Song argue that blockchain technology comes with significant tradeoffs ranging from the high costs of development and maintenance, to the challenges of coordinating complex incentives across many parties. Bitcoiners view capital-b “Blockchain” and “tokenization” advocates as missing the point: with a distributed ledger hammer, every incentive problem looks like a nail.

Ethereum’s marketing from late 2016 proposed “unstoppable applications”, enabling developers to do lots of things, many of which have not been invented yet. While Turing Completeness may have its advantages, it does not come without significant tradeoffs.

Ethereum’s marketing from late 2016 proposed “unstoppable applications”, enabling developers to do lots of things, many of which have not been invented yet. While Turing Completeness may have its advantages, it does not come without significant tradeoffs.

Many Silicon Valley investors have historically thought of the killer app of blockchains as creating new markets, with Naval Ravikant famously noting that blockchains can replace networks with markets. Pantera Capital CIO Joey Krug sees disintermediation of traditional companies as a core part of their “blockchain technology” thesis, suggesting that in their strongest form, blockchains can create marketplaces in industries far from financial services, massively up-ending traditional businesses in the process:

Blockchain tech is good for multi-sided marketplaces — particularly for finance. Other use cases, which really just converge with financial markets, include: file storage markets like Filecoin; computational markets; markets for items in video games; namespaces like Handshake; regular betting/gambling like FunFair; and sharing economy protocols like Origin. These projects will fuel a classic disintermediation play: cut out the existing profit-seeking corporations and replace them with software. As software eats the world, software is eating software.

Silicon Valley’s bias for the unconstrained view is straight-forward. By defining networks like Bitcoin as software-first, the role of the technologist precedes that of a monetarist. As such, “blockchain” simply becomes one amongst a number of emergent platforms in the ever-evolving internet infrastructure (Web 3.0). In “What comes after open source?”, Andreessen Horowitz’s Denis Nazarov elegantly explains this view:

Years of state accumulated by innovative companies produced tremendously useful services (search, maps, social, commerce), but further combinatorial innovation is off-limits to outside developers and entrepreneurs. Rebuilding services from scratch on the same terms and this late in the game is hopeless.

As crypto networks evolve, they are likely to provide strong incentives to unlock further state and create open services in many areas dominated by closed ones today. Open services powered by crypto networks will present unprecedented opportunity for a new generation of developers and entrepreneurs to innovate.

The Use of Language

The technologist’s articulation of the potential of blockchain technology rejects current constraints with a bias to technological progress. Not seeing this vision is often attributed to a lack of imagination on the part of the “doubters.” Who could’ve seen the potential of the internet in 1995 given the nascent state of internet architecture or the explosion of mobile applications transforming the world given the limited capabilities of the first iPhone? Sowell clarifies:

Intractable problems with painful trade-offs are simply not part of the vision of the unconstrained. Problems exist only because other people are not as wise or as caring, or not as imaginative and bold, as the unconstrained.

This is visible even in the linguistic choices of the unconstrained view, with Sowell noting that “the vocabulary of the unconstrained is filled with words reflecting their rejection of incremental trade-offs and advocacy in categorical solutions.”

More generally, the use of language becomes a strong reflection of an individual’s views. The term “shitcoin minimalist”, for instance, indicates a constrained view of the potential of blockchain-based solutions to human problems.

The term “Bitcoin maximalism” itself was a derogatory claim made by Vitalik Buterin, who started Ethereum after categorical rejection of his proposals to materially expand the available feature set on Bitcoin. It has since been weaponized, with Vitalik noting that “I do wish ill on bitcoin maximalism, but only because bitcoin maximalism as an ideology seeks elimination of all non-bitcoin platforms.” While the term has been co-opted by Bitcoiners to reflect a descriptive monetarist view rather than a prescriptive ideology, it is still a major point in the multi-coiners sieve to discount Bitcoiners’ claims, with Vitalik clarifying his view, even going so far as to use the word “constrain”:

Because I view single-coin maximalism as an oligarchic rent-seeking ideology that seriously constrains the possibilities of cryptocurrency innovation and makes it dependent on a political process (Bitcoin governance) rather than market competition?

Sowell preempts this conflict in his work, clarifying that “the anointed often place permanent labels on people, on the basis of transient circumstances” in order to more solidly position themselves as the underdog, fortifying “us v. them” dynamics. These labels aren’t useful — the interests of a few “toxic” Bitcoiners don’t reflect the views of most bitcoin holders, who are not even aware of the nuances of online cryptocurrency discourse.

Bitcoiners push back on this unconstrained view further, noting that they are largely divorced from science. Even the strongest proponents of the unconstrained view acknowledge the delta between the realities of today’s technology and appeal to tomorrow’s, with Walden further noting:

How exactly this will work is very much in the realm of open research. Proponents of “server era” architectures posit that a “cloud era” experience will emerge through standardization and abstraction of inter-blockchain communication among heterogeneous blockchains. Others, like Ethereum 2.0 (Serenity) and Dfinity, are converging on sharded versions of homogenous, turing-complete chains. And still others are researching entirely new architectures that move computation off-chain.

Through the lens of technological utopianism, or nirvana fallacy, feasibility is an after-thought to be attacked by a portfolio of diversified bets — the venture capital model — rather than an exploration of tradeoffs in an ever-exploding design space.

Episode II: The “fairness” of crypto distribution

Since the very beginning, debates about the “fairness” of various cryptocurrencies have sparked fiery conversation about what future wealth distribution should look like. This is expected — if cryptocurrencies actualize the full cypherpunk vision for the future, they represent one of the greatest wealth transfers of all time. With discussions of current income inequalities dominating global discourse, the potential for cryptocurrencies to exacerbate existing problems have been top of mind for many.

Over the years, there have been many attempts to quantify this disparity, including Balaji Srinivasan’s work exploring different networks’ Gini coefficients. These research efforts have sparked outrage from cryptocurrency enthusiasts and external critics alike, including:

Dogecoin creator Jackson Palmer:

The institutionalization of cryptocurrency will heavily re-centralize both power structures and token distribution. So you can say goodbye to much of the original vision for the technology.

Cryptocurrency analyst Ferdous Bhai:

80%+ Bitcoins have been distributed. 1) What type of people own these coins? 2) Do we want to enrich these holders via hyperbitcoinization? 3) Will the Bitcoin-rich use their wealth for good, or will they continue to oppress and exploit? Nobody talks about this.

Additionally, NYU professor and notorious cryptocurrency critic Nouriel Roubini remarks that “the inequality coefficient of BTC is worse than North Korea that has the worst inequality on earth.”

This conflict is another example of the strain between bottom-up constrained views of Bitcoiners, who believe attempting to design “ideal” wealth distribution is futile, and critics, who believe that Bitcoiners are “unfairly” rewarded for their early adoption. Defenders of the constrained view maintain that Bitcoin’s purpose is simply offering a non-sovereign money alternative — explicitly money that is designed not to be confiscated or debased — and that the distribution of bitcoins is perfectly calibrated by the free market to reward investors based on their place in the risk curve. Some further argue that given empirical suggestions that ownership concentration turns over with market cycles, concern over distribution is excessive — a problem solved by free markets.

Where holders of the unconstrained view project their desire for a certain wealth distribution in society, the constrained view clarifies that this is a violation of Bitcoin’s single purpose: preventing forced wealth redistribution. Sowell, once again, thoughtfully comments on wealth disparities in practice:

If one believes that income and wealth should not originate as they do now, but should instead be distributed as largess from some central point, then that argument should be made openly, plainly, and honestly. But to talk as if we currently have a certain distribution result A which should be changed to distribution result B is to misstate the issue and disguise a radical institutional change as simple adjustment of preferences. The word ‘distribution’ can of course be used in more than one sense…. What is really being said is that numbers don’t look right to the [unconstrained]–and that this is what matters, that all the myriad purposes of the millions of human beings who are transacting with one another in the marketplace must be subordinated to the goal of presenting a certain statistical tableau to [unconstrained] observers.

Despite this, conflicting visions persist. More ambitious experiments than ever are being pushed, including attempts to create “UBI via mass airdrop” or Bitcoin-alternative money systems specifically designed to prevent long-time wealth hoarding. Subscribers to the constrained vision push back against these forms of idealism with practicality: despite having good intentions, early iterations of these systems are often naively designed and ignore the second or third-order effects of top-down incentive manipulation. In many cases, these policies could end up hurting those they purport to help by creating gamifiable or broken incentives that exacerbate existing inequalities.

Episode III: Governance

The meta-problem of open-source protocol governance has been a longstanding debate where a fault line can once again be identified along the constrained and unconstrained divide.

The constrained vision believes that optimal governance is achieved through a bottom-up approach that attempts to minimize subjectivity and maximize trustlessness, while the unconstrained vision believes optimal governance is achieved through a formalized on-chain approach that interfaces with existing, top-down legal frameworks.

Nick Szabo’s mental model of wet code and dry further illustrates the nature of these conflicting visions. At the highest level, “wet code” is interpreted by humans, and “dry code” is interpreted by computers. Examples of wet code include law and traditional contracts. Examples of dry code include smart contracts, secure property titles, and the domain name system. Human language might be somewhere in between wet code and dry: if a computer program is able to translate text to multiple languages, for instance, human language may be considered dry.

The distinction between wet code and dry raises questions around the extent to which formalizing governance is possible without exposure to human subjectivity. If wet code is inherently human-readable and dry code computer-readable, the constrained vision would posit that transforming a wet code legal system into dry code would not only add additional complexity but also introduce elements of human subjectivity.

Because the specifics of law and governance are complex and unknowable, the constrained vision opposes fully formal on-chain governance: implementation of “law as code” becomes heavily subjective and unlikely to account for the unpredictable changes in the real world.

Since avoiding human subjectivity and maximizing a network’s trustlessness is the constrained vision’s top priority, “law as code” becomes unattractive. As Bitcoin Core developer Matt Corallo highlights, “trustlessness is the ability to use Bitcoin without trusting anything but the open-source software you run.” The constrained vision posits that a formalized governance system, which adds unyielding subjectivity to the open-source software, would come at the cost of automated integrity and trustlessness.

Through formalized on chain governance, changes to dry code are completely arbitrary, a reality the constrained vision avoids by prioritizing and questioning the process first. As Sowell suggests:

To those with the vision of the anointed, it is simply a question of choosing the best solution, while to those with the tragic vision the more fundamental question is: Who is to choose? And by what process, and with what consequences for being wrong?

A software’s formal governance system is created from a dry code implementation of something that is inherently wet code. As a result, the control and trust of the software transfers to humans. Under the unconstrained vision, humans should be able to change a network’s implementation in an ongoing fashion, as humans are the final arbiters of truth. As such, the vision pushes back on the subjective claim that trust-minimization through software automation is optimal, refusing to accept such a claim as “law.”

In practice, under the constrained vision, automated governance is limited to maintaining the set of verification rules, as seen in Bitcoin’s governance model. In the case of a failure in a wet code process, such a system would resort to a fork, a change in the protocol influencing the validity of the set of rules. Since forks are seen as bugs to the unconstrained, the value proposition of an on-chain governance system is that it precisely avoi ds forks and encourages high upgradeability. However, by formalizing governance, the risks of undergoing a fork under what at the time would have been considered to be a perfect implementation may potentially speak to the subjective nature of the implementation. For the long term sustainability of the protocol, the constrained vision posits this to be detrimental.

Episode IV: Proof-of-work vs. Proof-of-stake

Bitcoin’s proof-of-work is an embodiment of the constrained vision, a mechanism to work around fundamental limitations rather than re-engineer them. First explained by Nick Szabo in Money, blockchains, and social scalability, Bitcoin’s proof-of-work accommodates our cognitive limitations and behavior tendencies by making a necessary and intentional tradeoff: greatly sacrificing computational scalability to improve social scalability.

A feature to the constrained, a bug to the unconstrained.

The ability to participate in an “institutional technology” is predicated on the technology motivating participation and protecting the system and its participants from malicious activity. By improving social scalability, which proof-of-work does so effectively, the number of people who can beneficially participate in the system is maximized. Therefore, the constrained, “proof-of-work” vision posits that Bitcoin’s success should not be determined by its computational efficiency but by its ability to increase social scalability through trust minimization.

What the unconstrained vision deems computationally inefficient and unscalable, the constrained vision not only deems an intended tradeoff, but a fundamental feature: specialized, dedicated hardware should perform a function whose sole output is to prove that the computer did indeed execute a costly computation. As Nick Szabo highlights, “prolific resource consumption and poor computational scalability unlocks the security necessary for independent, seamlessly global, and automated integrity.”

While an implementation of both computational and social scalability is optimal, the constrained vision acknowledges that it cannot be done without compromising security. Embedded in computer science is a fundamental understanding of tradeoffs in security and performance where inevitably, automating integrity requires high resource utilization. Even with breakthroughs in computer science, the constrained vision recognizes that total integrity and absolute trustlessness is infeasible, making the delicacy of explicit and intentional tradeoffs all the more imperative. As such, the constrained vision fully accepts that such tradeoffs are unavoidable, and “it is probable no such big but integrity-preserving performance improvement is possible.” [4]

To the unconstrained vision, the assumptions around proof-of-work are entirely different. Instead of asserting that proof-of-work sacrifices computational inefficiency for social scalability, the unconstrained vision asserts that proof-of-work unjustifiably consumes significantly more resources than it creates, making it a wasteful and archaic system in dire need of improvement.

A commonly used statistic the unconstrained vision employs to illustrate proof-of-work’s “wastefulness” is a measurement of the amount of energy the system expends as a proportion of the total transaction volume the system processes. By employing such a statistic, it becomes obvious why under the unconstrained view, proof-of-work is so scandalously inefficient: “Bitcoin consumes five Hiroshima’s worth of energy per day” only to process “a mere fraction of what a payment service like Visa processes.”

The use of this argument to illustrate proof-of-work’s wastefulness implies that trust minimization is not viewed as a necessary feature in the unconstrained vision. If it were, comparing Bitcoin to Visa would be futile: Visa does not provide the same improvements in social scalability through trust minimization precisely because it is more “computationally efficient”. Such a comparison not only dismisses the existence of limitations, but attempts to associate two completely unrelated variables (i.e. energy expenditure and transaction volume are not functions of each other). As Sowell highlights, wrongful association of these variables leads to “statistical extrapolation without any analysis of the actual processes from which these numbers were generated.” [5]

A costless alternative?

Deeming proof-of-work wasteful suggests a cheaper, more prudent alternative exists. To the unconstrained vision, the reason proof-of-work has not fully succumbed to an alternative may come from a lack of care for the environment or a lack of imagination of technological advancements as Emin Gun Sirer suggests:

100 years from now, future generations will talk about the PoW craze with the same bemused view we hold for other mass manias. The absurdity of wasting energy to make chicken scratch marks on an electronic ledger is going to become more obvious. We are going to look back the same way we look at the use of CFCs and leaded gasoline. We should replace it with systems that can do better.

As previously highlighted, the unconstrained view is to remove specific negative features in the existing situation to create a solution. In the context of proof-of-work, the question posed by the unconstrained is then: “how can we remove the computational inefficiency and energy wastefulness of proof-of-work to create a better sybil-control mechanism and consensus algorithm?”

Attempting to answer this question, mechanisms like proof-of-stake have emerged as the most popular solution, as Ethereum’s Vitalik Buterin highlights:

“The philosophy of proof-of-stake is not ‘security comes from burning energy’, but rather ‘security comes from putting up economic value-at-loss’.

In a proof-of-stake system, a blockchain appends and agrees on new blocks through a process in which anyone who holds coins inside of the system can participate and the influence an agent has is proportional to the number of coins (or ‘stake’) it holds. This is a vastly more efficient alternative to proof-of-work ‘mining’ and enables blockchains to operate without mining’s high hardware and electricity costs.”

Under the unconstrained view, proof-of-work is classified solely as a sybil-control mechanism. As such, there is greater justification for removing energy spend on coin production. Emin Gun Sirer explains:

The energy spent on coin production is purely wasted, it provides no price floor for coins, it is value leaked out of the system. Much like how the high cost of printing Bahts doesn’t guarantee value higher than USD. It’s just the cost of competition between miners.

Thus, the goal in the unconstrained vision is to implement an inherently costless system without leakage. In proof-of-stake, network participants are not required to use inordinate amounts of energy to maintain ledger immutability, significantly reducing labor intensity. A reduction in labor intensity would be more fair and help encourage community participation due to lower barriers to entry. Specifically, the unconstrained vision claims that taking mining out of the hands of entities with access to excessive amounts of low cost energy would help redistribute the work evenly and lead to a more democratized system. By removing the feature that secures value in a proof-of-work system, security in turn is derived from the value stored within the system itself. As David Yakira notes, “in a sense, a PoS system is recursive, augmenting the value it stores implies better security which further allows the value to increase and so on.”

Under the constrained vision, however, defining proof-of-work as merely a sybil-control mechanism is non-exhaustive and trivializes its purpose. Proof-of-work is also seen as essential for maintaining unforgeable costliness “giving digital blocks real-world weight” and enforcing a predictable, meritocratic distribution mechanism.

Because the constrained vision believes there to be “no solutions, only tradeoffs,” a costless mechanism without leakage would also be definitionally impossible, as Paul Sztorc notes:

“Switching the payout-trigger to a social or political dimension would merely transpose the work-expenditures correspondingly to the realms of bribery and propaganda.

If an object has value, people will spend effort to chase it, up to whatever the object is worth (MC=MR). This effort is also “work”. [Thus], a stable solution to these problems is definitionally impossible, as there is always an incentive to work until marginal cost equals marginal revenue.”

The Future Remains To Be Built

As we’ve highlighted, these divisions between cryptocurrency enthusiasts, investors, and builders can be seen across the “unconstrained” and “constrained” axes, two conflicting ideologies that transcend geography, professional associations, or backgrounds.

We believe that the most likely outcome after the full possible actualizations of these visions is convergence in some form. While the future remains uncertain, a conflict of visions persists because in reality, visions are all we have to focus on ahead of a multi-decade roadmap of adoption and integration.

The dominant visions of the constrained view are not mutually exclusive with the more abstract unconstrained view. While on the surface, inter-currency battles persist, the final boss (third party disintermediation) — which unites everyone alike — is shared. Though differences emerge upon squinting, high-level goals are not divergent. Privacy-aware cypherpunks want to see the destruction of ad-driven technology monopolies and Bitcoin remains a useful tool against tyrants independent of political, social, or religious affiliation. While cryptocurrency adoption appears zero-sum, experimentation is at the core of open-source and expands the size of the pie in the short-to-medium term by bringing new entrants to the market with disparate views while concurrently validating existing implementations.

It may be that for creating a global money, only a tightly constrained, focused view can prevail as launching a system mimicking a Swiss bank in your pocket requires this level of carefulness. If indeed blockchains represent a major evolution in computing, those systems may follow an evolving philosophy closer to a traditional software release cycle with constantly iterated release cycles.

These debates will be reminisced upon like early internet debates about the ideal protocol standard or intranets and the Internet (earlier generations’ blockchains v. bitcoin) or debates even further back about the viability of inferior monetary metals to gold. Ultimately, winners will emerge out of today’s conflicting visions invoking “how did we not see that coming?” commentary in the process.

For now, the future remains to be built.