51% attack - apparently very easy? refering to CZ’s “rollback btc chain” - How to make sure such corruptible scenario can never happen so easily?

| If you find WORDS helpful, Bitcoin donations are unnecessary but appreciated. Our goal is to spread and preserve Bitcoin writings for future generations. Read more. | Make a Donation |

51% attack - apparently very easy? refering to CZ’s “rollback btc chain”

How to make sure such corruptible scenario can never happen so easily?

Conversation from Peter Wuille, Greg Maxwell, Fernando Nieto

Posted May 11, 2019

Peter Wuille

I was shocked to see binance CZ comment to literally “roll back” the bitcoin chain by just “calling” in some favors from “friendly” Asian miners .

This ONE person could effectively do it??? I mean are we all in a bubble, in some kind of utopia then, to think that the chain’s decentralization makes it “bulletproof” and resistant to collusion by miners?

(1) This is fundamental question: How are our highly regarded and brilliant Devs of bitcoin explaining such situation where only a handful of persons´ interests could essentially be enough to do a majority 51% attack?

(2) And secondly, are there active debates about how to mitigate such situation in the future, what technical aspects implemented in the btc chain (or to be implemented) could be helpful?

This huge mining farms are essentially very disturbing. it is like in proof of stake , where the “richest” has most power. And in the PoW mining case , its similiar just that the “biggest hardware” has most power.

we have to try somehow to eliminate such easily corruptible scenarios, right?

in todays digital world, there are plenty of collusion examples of even more than 1000 different persons involved.

Handful of colluding majority miners would be a piece of cake, right?

Thank you for explaining to me this issue . I hope sincerely that this is taken up by our awesome dev community, or maybe I am just misunderstanding everything.

Peter Wuille

Disclaimer: I believe this question may be primarily opinion-based and not very appropriate for this site, but there are a number of technical misunderstandings that can be clarified along with it, so I’ll give it a shot.

There are many nuances involved here, and I fear that a large part of them didn’t reach as much of an audience as the exchange announcing “we decided not to do it”. I believe this was a poor choice of words, as the decision they made wasn’t whether or not to roll back the chain; only whether or not to offer a bounty for doing so. I personally believe it would be very unlikely that the alternative would have actually resulted in a deep rollback.

Let’s analyze the situation from a number of perspectives.

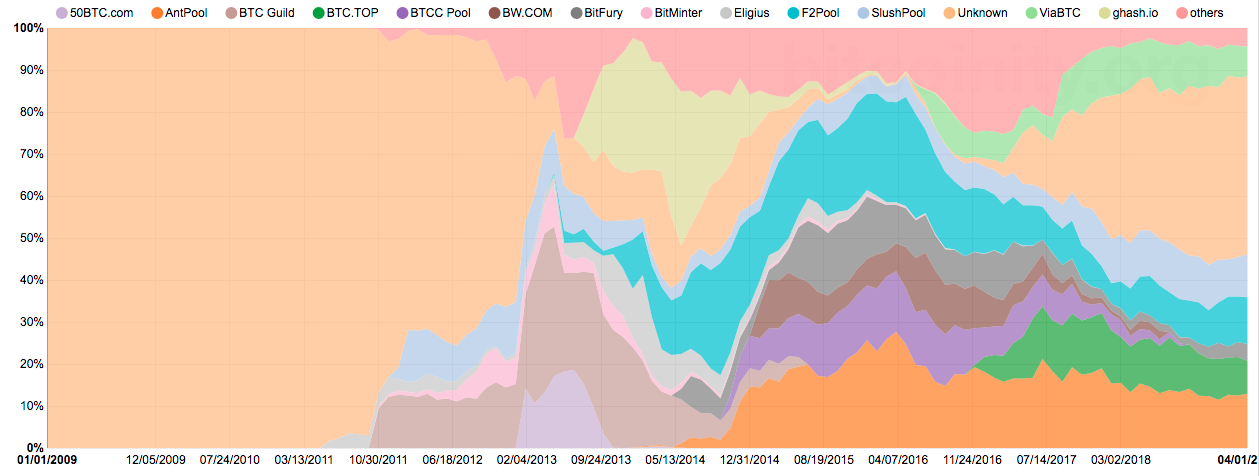

If we only consider miner’s actions, is it theoretically possible for them to roll back the chain? Yes. If you’re wondering if there is a small number of mining company CEOs in the world, which, if all together convinced, with complete disregard for their own financial interests, the health of the network, or legal repercussions, could decide to roll back the chain to a point before the theft, the answer is yes. This is the reason why people care about mining decentralization, and permissionlessness of entering the mining market. However, unless it’s not just a majority of the hash rate that is on board with this, but actually close to all the network’s hashrate (a substantially harder problem, as there are many small miners in addition to the few big ones), this would likely have take days or even weeks (if it’s close to 50%), a time during which many things can happen - including a public outcry and a UASF-style fork to prevent the rollback from being accepted by the ecosystem. If considered over an even bigger timescale, events like this may even incentivize people and businesses to become miners, in order to reduce the influence of large pools.

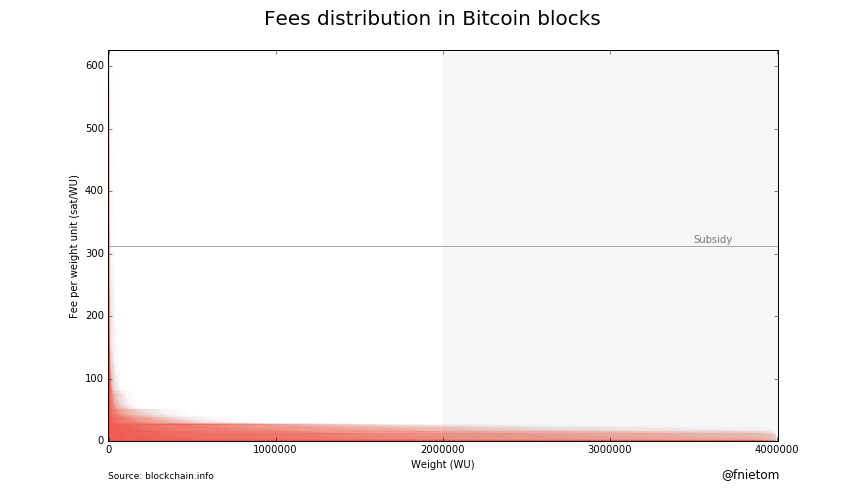

Assuming miners maximize short-short term profit, would it be financially interesting to rollback? No. Even if we assume that everyone in the network is acting selfishly to try to maximize their own (short-term) profit, and ignores the protocol rules and the possible repercussions from doing so, it is not. By the time the information about the theft became known, the transaction was already confirmed several hours before. During those hours, miners had created dozens of blocks, which together earned several hundred BTC in subsidy and fees. The exchange would need to offer at least that amount to the affected miners, to compensate them for the income they’d lose from rolling back those blocks, before it would even be worth discussing. Let’s call this the rollback cost R. As the stolen amount was in the thousands (let’s call this S), that seems like a reasonable option. However, nothing prevents the thief from using (part of) the stolen funds to do the same. Every BTC offered by the exchange above R can be countered by an equivalent amount offered by the thief. And then it becomes clear that the thief has the upper hand: the exchange can at most gain S-R by a rollback, but the thief stands to gain S by not having a rollback. A theoretical possibility is a bidding war between the exchange and the thief, where both increase the amount paid to make miners act in their favor. The end game of this is that the exchange offers S-R, the thief offers slightly more and keeps R, and miners are paid S-R by the thief, and no rollback happens.

What would happen in the real world? Theoretical models are interesting to study, but in reality many more practical considerations exist. I believe those too are generally in favor of no rollback:

- Coordination between distrusting miners (especially close 100% hashrate) is hard, and would take time. The more time it takes, the less advantageous a rollback becomes (see the above point), and the more damage would be done to the ecosystem (see the next point).

- An hours-long (in the very best case) or a weeks-long (in the worst case) rollback would monumentally hurt the ecosystem, and likely undermine the public’s confidence in the system to the extent that it would severely reduce the profitability of many parties involved (including miners and the exchange itself!).

- Even ignoring all the above, miners may not be willing to take a bribe to rollback because of legal reasons if they’re publicly known (which they mostly currently are). They may equally not want to take stolen money as a bribe, so this cuts in both directions. This point becomes weaker if the mining ecosystem is more decentralized, but that would also make coordination harder.

- As I pointed out above, in the extreme scenario where such a rollback is actually happening, the public has time to react. If a sufficiently large group of economically relevant parties in the network refuse to accept the rollback, miners have no choice but to go along with that. This is a last-resort option, and likely damaging to the ecosystem on its own, but it is an option.

So to summarize: in theory there are absolutely ways in which a rollback could happen, and it’s good to be aware of those. In reality, the security of the system relies on economic incentives already which are nontrivial to analyze. It however seems very unlikely that in the case of a theft a deep rollback is a reasonable outcome.

Gregory Maxwell

You might want to elaborate on your short term profit formula to consider that R depends not just on the existing blocks but on the share of honest hashrate. E.g. In the simplified theoretical model R is infinite after confirmation with >50% hashrate honest. At just under 50% honest it’s finite but much larger than the number of blocks that need to be replaced. Only at 0% honest does R equal just the cost of blocks that need to be replaced. Coordination challenges alone assure that some hashrate would behave honestly.

Gregory Maxwell

(adding some color) Some discussion I saw suggested that people promoting this believed they only needed to achieve >50% hashpower, which caused them to overestimate the feasibility. Reorging with only slightly over 50% would take weeks– even months, creating massive disruption if successful, and virtually guaranteeing an effective public initiative to block it. In such an event once the rollback began, users would advise each other to use the ‘invalidateblock’ debugging command to make their nodes ignore it. [I also had multiple users ask me to review patches ahead of the fork that would have blocked it, I told them I thought they were over-reacting and that this was a nothing burger. :)– but a patch would only be needed before a fork existed, and clearly people were ready to start responding to this only on the basis of twitter chatter]

Fernando Nieto

here a are a few things to take into account when we consider the probabilities of a reorg to be successful:

- If the reorg is shallower than 100 blocks (COINBASE_MATURITY), the attacker can minimize the amount of direct victims. But if we are talking about a deeper one, not only the payments he wants to revert may have been spent, mixed with other inputs and all those coins owned by other innocent people, this would also apply to coinbases earned by honest miners. The longer it takes to perform the reorg, the higher the amount of victims and their value at stake.

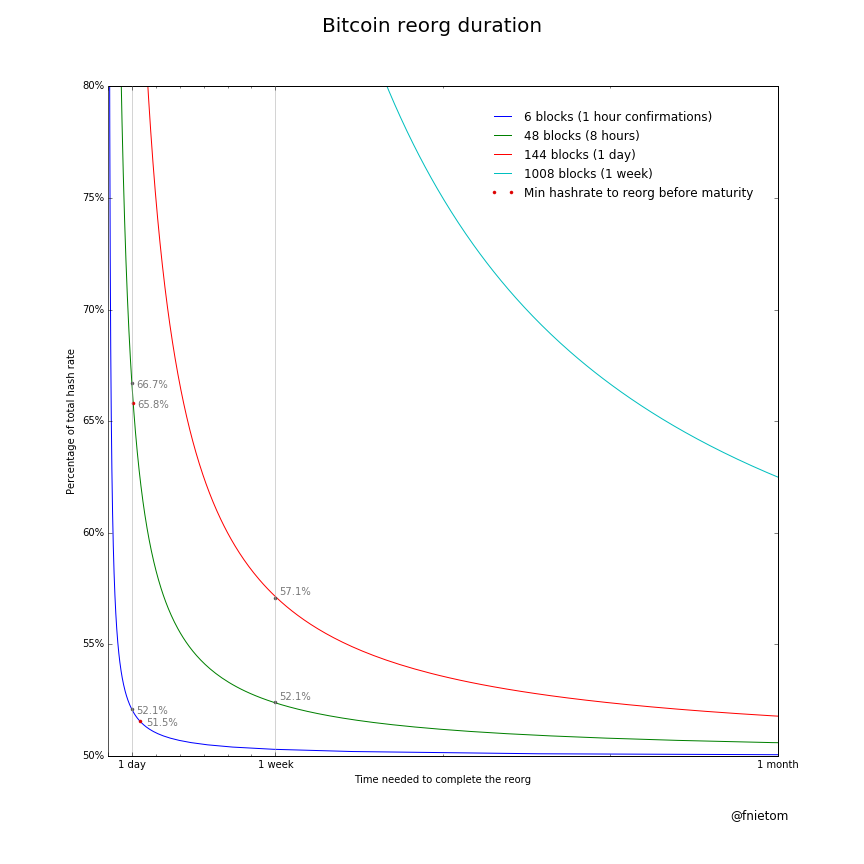

- The attack may take a long time. The fraction of miners participating (via direct control or bribes) and the amount of blocks to revert will determine how long.

For example, to revert just 6 blocks (1 hour worth of confirmations) before coinbases start maturing, the attacker will need to get immediate control over 51.5% of the hashing power. If he falls short of that percentage or requires more time to convince some of the miners, it will take him over 33 hours and reverting more than 100 blocks in total, so rewards from the first blocks may have been spent already.

- If the attack uses existing mining capacity, during the time it takes to reorg the chain, the capacity on the longest chain would be reduced to less than half of the usual capacity. You can expect this to have an impact on fees and miner rewards, as the offer for transaction confirmations is not able to satisfy demand users will have to fight for the reduced space available. Higher rewards on the honest chain will put additional pressure on miners carrying the attack. It’s difficult to predict how high they can go in the middle of all that FUD, with many people rushing to move coins to trade. enter image description here

- A significant reorg doesn’t affect just direct victims, every bitcoin holder would be affected due to a diminished confidence in the system, a reduction in Bitcoin utility and a drop in the price of the coins as a consequence.

PoW is a trust-minimized market signal enabling us to scale social consensus. But, if somebody builds a heavier chain with a lower value, breaking PoW trust-minimization, users can choose not to follow it and make a UASF, invalidating the reorg:

$ bitcoin-cli invalidateblock "blockhash" - Coins in both chains are only as valuable as their chances to become part of the winning one. Miners coordination, unusually high fees in the longer/honest chain and UASF risk during the reorg attack are all factors against reorg-coins having as much value as those in the honest chain. This makes even more challenging to use reorg-coins to bribe miners.

How can we make reorgs even more difficult? @LukeDashjr provided the first two of these ideas, that would help us achieve stronger immutability:

- If users set individual checkpoints in their nodes, this would discourage reorg attempts and split the chain if one happens, leaving it for market to discover the value of each chain when PoW consensus assumptions break down.

- Use pool swapping rule introduced by BFGMiner to prevent miners from wasting work on stale blocks. If one pool implements a reorg policy (even if it is trying to earn bribes), miners will refuse to ditch previously validated blocks and switch to a pool working on the newest block.

- @TheBlueMatt’s BetterHash mining protocol would have a similar effect, making practically impossible for mining pools to enforce an ordering of transactions, hence removing their ability to censor some of them.

- The more independent miners, the more difficult it will be for anybody to coordinate them and try to 51% attack the network with existing mining capacity. Currently over 40% and growing.